Fans of the old Superman comics no doubt remember Bizarro World, the cuboid planet where everything is backward. Denizens of this parallel world are distorted replicas of their Earth-based counterparts, and they live by a Bizarro Code which dictates that being good or doing the right thing is a crime.

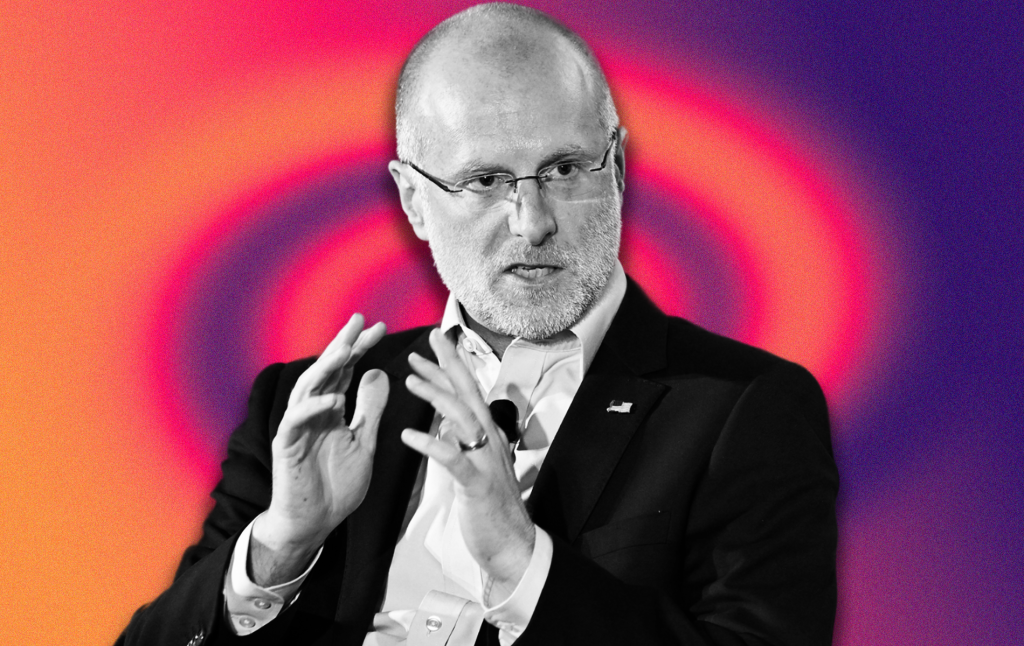

Apparently, the phenomenon is not confined to fiction. Ever since Donald Trump’s Inauguration Day appointment of Brendan Carr to chair the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the agency that licenses broadcast stations has become a Bizarro World version of its former incarnation. And there is some reason to suspect Carr himself has somehow been replaced by his Bizarro doppelganger.

Carr, who has been an FCC commissioner since 2017, used to say things that reflected an understanding that the government’s authority to regulate the media is sharply constrained by the First Amendment. When Democratic congressmen tried to exert political pressure on broadcasters over their coverage of COVID-19 and the 2020 election, for example, Carr called it “a chilling transgression of the free speech rights that every media outlet in this country enjoys,” adding in no uncertain terms, “a newsroom’s decision about what stories to cover and how to frame them should be beyond the reach of any government official.” Or when members of Congress urged the FCC to reject a Miami radio station transfer based on the political viewpoints of the proposed new owner, Carr rebuffed this effort “to inject partisan politics into our licensing process,” correctly calling it “a deeply troubling transgression of free speech and the FCC’s status as an independent agency.”

Less than a year ago Carr proclaimed the United States does not need “the FCC to operate as the nation’s speech police,” adding, “if there ever were a time for a federal agency to show restraint when it comes to the regulation of political speech and to ensure that it is operating within the statutorily defined bounds of its authority, now would be that time.” Back then, Carr wore an American flag lapel pin, suggesting a commitment to the Constitution he swore to uphold. He’s since traded that for a Donald Trump lapel pin that looks like a prize fished out of a cereal box, and it suggests an allegiance to … something else.

Since the November election, “Bizarro Brendan” has taken over in earnest, aggressively asserting the kind of government power over speech and the press that normie Brendan professed to abhor. In interviews, social media posts, and by his official acts, Carr has said that the broadcast networks (except Fox) should be investigated for “news distortion,” that media mergers should be held up because of network news decisions, that public broadcasters should be investigated for their private sponsorships (but really for their editorial policies), and that Big Tech companies should be brought to heel because of their moderation practices. This last example is even more bizarro than the others since the FCC lacks jurisdiction over social media and computer companies, and because it came from the same guy who not long ago insisted “the American people want more freedom on the Internet—not freewheeling micromanagement by government bureaucrats.”

Right before Trump was inaugurated for his second term, the FCC’s staff took the kind of action the old Brendan would have applauded. Or so his former rhetoric might suggest. The commission’s media bureau dismissed an effort to deny license renewal to the Fox Philadelphia affiliate for its news reporting on the 2020 presidential election. The same day the enforcement bureau dismissed a complaint seeking to penalize WCBS for the way 60 Minutes edited its Kamala Harris interview; another seeking sanctions against an ABC station because a newsman fact-checked Trump during the presidential debate; and a complaint alleging NBC violated the FCC’s “equal opportunities” rule when Harris appeared on Saturday Night Live shortly before the November election (even though the network provided candidate Trump equal time). Outgoing Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel said at the time the dismissals were necessary because the FCC “should not be the President’s speech police” and cannot act as “journalism’s censor-in-chief,” which sounded a lot like Carr before he was body-snatched.

But Bizarro Brendan was fully in charge by the inauguration, and one of his first official acts as chairman was to reinstate the investigations of CBS, ABC, and NBC (but, curiously, not the proceeding against Fox). He doubled down on CBS, seeking public comments on whether the network should be punished for “news distortion” and holding up FCC approval of a proposed merger between Skydance Media and Paramount Global (which includes transfer of 28 owned and operated CBS stations) while the complaint is being reviewed. And this pressure is being exerted on CBS in support of a private lawsuit then-President-elect Trump filed against CBS in Texas frivolously alleging the Harris interview on 60 Minutes was consumer fraud.

Since then, Carr has worked out a weird call-and-response routine, where he will post on social media his latest beef with particular networks, which then—miraculously—become the subject of complaints. On April 16, for example, Carr hinted in a social media post that Comcast (the parent company of NBC) committed “news distortion” with its coverage of Kilmar Abrego Garcia—the man the Trump administration mistakenly deported to El Salvador but refuses to return to the U.S.—for, among other things, referring to him as a “Maryland man.” Less than a week later, the Center for American Rights, the partisan group behind the 60 Minutes complaint, filed a news distortion complaint against not just NBC, but ABC and CBS as well. Carr’s post on X was cited as a principal source for the complaint.

The news distortion policy is a leftover corollary of the long-defunct Fairness Doctrine under which the FCC purported to evaluate news coverage of controversial issues to ensure “balance.” The agency ended that policy nearly 40 years ago during the Reagan administration under a principled FCC chairman, Mark Fowler, who foresaw that such regulatory authority could not be reconciled with the First Amendment and inevitably would be misused as a political weapon. Since then, the “news distortion” policy has been a dead rule walking, just waiting to be overturned in the right case.

Carr well knows that such complaints are an abuse of process and a violation of the First Amendment. The FCC’s authority to rule on “news distortion” has always been extremely limited because the agency recognized from the beginning that it cannot act as the “national arbiter of the truth” and that doing so “would involve the Commission deeply and improperly in the journalistic functions of broadcasters.”

It is highly doubtful the current FCC will terminate the moribund policy on its own, even though it has opened a proceeding to delete outdated and unconstitutional rules. The news distortion policy has proven to be too useful a tool for bludgeoning the media in a politicized FCC.

Indeed, the only way this administration makes sense is to understand it as operating under the Bizarro Code. On Day 1 the president issued an executive order purporting to bar any federal officer from conduct that would unconstitutionally abridge free speech, yet Carr’s FCC has been actively involved in threatening media companies—including those beyond its jurisdiction—and reinstituting bogus investigations of broadcast news judgments. Another executive order prohibited weaponizing federal agencies against political opponents, yet that has been Carr’s primary occupation since becoming FCC Chair. In the Bizarro FCC, it makes no difference that, just last year, the Supreme Court held the First Amendment does not permit government officials to threaten legal sanctions in order to alter the speech of a private business; that the government cannot interfere with editorial judgments, including the private moderation decisions of social media companies; and that federal agencies like the FCC cannot override statutory commands, such as the Communications Act prohibition against any “regulation or condition” that interferes with freedom of speech. That’s because under the Bizarro Code, doing the wrong thing is the point.