Authored by Autumn Spredemann via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

Mexico’s delinquent water deliveries, in violation of an 81-year-old treaty with the United States, have exposed years of “blind eye” policies, rapid population growth, and hydrological changes, according to an expert at the U.S. Army War College.

Evan Ellis, research professor of Latin American studies at the college’s Strategic Studies Institute, told The Epoch Times that recent tensions over Mexico’s delinquent water deliveries have come from “years of looking the other way” on the part of the United States.

U.S. President Donald Trump has requested that the United States’ southern neighbor honor its obligation to deliver 1.3 million acre-feet of water to Texas. The amount totals almost 70 percent of a five-year water commitment that’s due in October.

“Just last month, I halted water shipments to Tijuana until Mexico complies with the 1944 Water Treaty,” Trump wrote in an April 10 post on his social media platform, Truth Social.

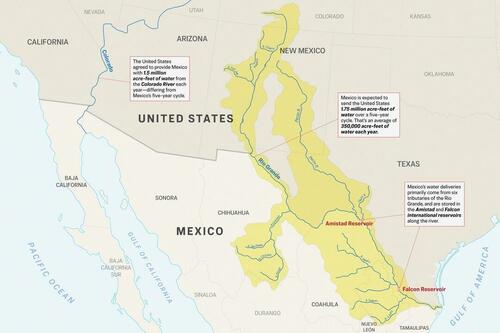

Under the reciprocal agreement, Mexico is expected to send the United States 1.75 million acre-feet of water over a five-year cycle. That’s an average of 350,000 acre-feet of water each year. The water deliveries primarily come from six tributaries of the Rio Grande, and are stored in the Amistad and Falcon international reservoirs along the river.

One acre-foot of water—one acre of water at a depth of one foot—is roughly enough to fill half of an Olympic-size swimming pool. Mexico’s average annual obligation is enough water to supply 700,000 to 1 million Texas households for a year.

In exchange, the United States agreed to provide Mexico with 1.5 million acre-feet of water from the Colorado River each year—differing from Mexico’s five-year cycle.

The Tijuana shipments that Trump said were halted were part of a non-treaty water request from Mexico.

The U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Western Hemisphere affairs said the United States denied such a request for the first time since the treaty was signed because of Mexico’s noncompliance with its water obligations.

“Mexico’s continued shortfalls in its water deliveries under the 1944 water-sharing treaty are decimating American agriculture—particularly farmers in the Rio Grande valley,” the State Department wrote in a statement on social media platform X on March 20.

According to the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC), which handles issues related to the 1944 treaty, Mexico has failed to meet its five-year delivery obligations three times since 1992. Each of those debts was carried over to the following cycle and ultimately paid.

Mexico also fell short in average minimum annual deliveries within the 2002–2007 and the 2015–2020 cycles. Those shortfalls were met very close to the end of the cycles—in 2020, within just three days of the deadline.

Although the deliveries were ultimately fulfilled, the unpredictable nature of water deliveries from the Rio Grande has impacted water users on both sides of the border.

The current cycle for both countries ends in October, but according to IBWC data, by March 29, just 28 percent—or less than 500,000 acre-feet of water—of Mexico’s water obligation had been delivered.

In response to a query about how much of the United States’ water commitment to Mexico has been met, IBWC public affairs chief Frank Fisher cited an agency graph showing that the United States had met about half of its 2025 commitment as of April 19.

In November 2024, the two countries agreed to a treaty amendment that would give Mexico more ways to meet its water obligation. Those options include providing water from the San Juan and Alamo rivers, which are not part of the Rio Grande tributaries specified in the treaty. The agreement also set up a working group to explore other sources of water.

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum said at a news conference on April 11, the day after Trump’s social media post announcing a delivery stoppage, that she expected an agreement in the coming days “that will allow the treaty to be fulfilled.” She called the treaty “fair.”

Sheinbaum told reporters that there would be “an immediate delivery of a certain number of millions of cubic meters that can be provided according to the water availability in the Rio Grande.”

In response to a query about whether Mexico had made that delivery, the State Department confirmed that Mexico had committed to making an immediate transfer of water, but it did not confirm that the delivery had been made.

The State Department stated on April 28 that the two countries had committed to developing “a long-term plan to reliably meet treaty requirements while addressing outstanding water debts—including through additional monthly transfers and regular consultations on water deliveries that take into consideration the needs of Texas users.”

Sheinbaum has blamed her country’s increasingly delinquent water shipments on extended periods of drought that have affected the Rio Grande.

“Talks are underway with the governors of Tamaulipas, Coahuila, and Chihuahua to reach a joint agreement to determine how much water can be delivered … without affecting Mexican producers, while also complying with the 1944 treaty,” Sheinbaum said during a news conference on April 15, referring to three Mexican states that border Texas. The Rio Grande serves as the international boundary.

Historically, Mexican farmers have contested attempts to increase water deliveries to the United States for fear of losing their crops.

In September 2020—before an October delivery deadline—farmers in Mexico’s Chihuahua state, which borders New Mexico and Texas, were involved in heated protests over government attempts to deliver 378 cubic meters of water to the United States, claiming that their livelihoods were at stake amid severe drought conditions. One protester was killed in clashes with the Mexican National Guard.

Downstream Dilemma

Maria-Elena Giner, then-commissioner of the IBWC’s U.S. division, told The Epoch Times on April 18 that the division is “in close contact with the administration regarding the need for Mexico to commit to predictable and reliable Rio Grande water deliveries.”

“We have continued to request that Mexico make monthly deliveries and provide a specific plan outlining how they intend to make up their historic shortfall in the next five-year cycle,” Giner said.

“At the same time, we are doing everything we can to assist impacted south Texas stakeholders, including alerting growers and irrigation districts about available federal and local resources and sharing our historical data on Rio Grande hydrology.”

Giner, a Biden appointee, resigned on April 21. She will be succeeded by William “Chad” McIntosh, who previously served as acting deputy administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency under administrator Lee Zeldin.

The 1944 water agreement between the United States and Mexico was struck at a time when groundwater was abundant, and droughts weren’t as lengthy. Both nations agreed to share water from two rivers that help define the international border: the Colorado River and the Rio Grande.

Like the Rio Grande in Mexico, the Colorado River in the United States has faced extreme drought in recent years.

Since 2000, the Colorado River, which originates in the Rockies and joins Mexico at the California–Arizona border, has experienced a “historic, extended drought” that has taken a heavy toll on regional water supplies.

At the same time, population and agricultural growth in Colorado River Basin states have grown exponentially over the two decade period.

Currently, the Colorado River Basin provides water to an estimated 40 million residents in seven U.S. states and irrigates more than 5 million acres of farmland.

Read the rest here…

Loading…