from the the-sides-have-flipped dept

Here’s a question about the First Amendment and social media companies that used to just be in the realm of crazy law school hypotheticals: What makes social media sites “state actors” subject to constitutional constraints? For years, we heard from some that merely talking to government officials was enough — at least according to Vivek Ramaswamy, RFK Jr., and (disgraced) Yale Law professor Jed Rubenfeld. They argued, with increasingly creative (and decreasingly convincing) legal theories, that if a White House staffer sent an angry email about content moderation, that transformed Meta into an arm of the state.

But now we have an actually interesting scenario: What if the government officials literally own and run the social media companies?

Ramaswamy and Rubenfeld wrote an op-ed in the WSJ arguing that Section 230 alone made tech companies into state actors. Then, Rubenfeld joined RFK Jr. to make this argument in court, after Meta suspended some of RFK Jr.’s anti-vax nonsense. That argument failed in court as judges (rightly) noted that none of this turned companies into state actors. There would have to be a much clearer (and more coercive) relationship between government actors and social media companies.

But now we face a situation that makes those earlier claims look quaint: two of the most powerful people in our government — Donald Trump and Elon Musk — literally own and control major social networks. Does that finally make these platforms actual state actors? After all, ExTwitter and Truth Social aren’t just getting stern emails from government officials — they’re directly controlled by a sitting President and the guy who appears to have totally unprecedented and unlimited authority to reshape the federal government.

At the very least, the argument is way, way stronger than what the likes of Rubenfeld and RFK Jr. were arguing in court.

Eventually, someone had to try to make this argument for real, and it appears that someone is a rando named Thomas Richards.

According to the complaint he filed last month in the Northern District of Texas (where ExTwitter now tries to force all lawsuits to be filed due to its notably Musk-friendly judges), Elon Musk has been shadowbanning him. And, the complaint argues, because of Musk’s government-status, that means that ExTwitter is a state actor, and thus any shadowbanning infringes on his First Amendment rights.

While I’ve argued this exact theory might have merit, Richards’ complaint is, unfortunately, a mess. Filed by an out-of-state lawyer (apparently ignoring local counsel requirements), it’s bloated with irrelevant details and conspiracy theories masquerading as supposed “religious expression.” The core claim — that low engagement on his posts proves shadowbanning — is weak on its face. But the legal theory presented is even worse:

The Court’s intervention is urgently needed because under the clear precedent of Brentwood Academy v. Tennessee Secondary School Athletic Association, 531 U.S. 288 (2001), when a private entity becomes “entwined” with governmental authority, it becomes subject to constitutional constraints. And here, the link is even tighter. X’s owner and controller, Elon Musk, simultaneously holds significant federal authority as a Special Government Employee heading the Department of Government Efficiency (“DOGE”), created by executive order on President Trump’s first day in office … This entwinement is further cemented by extraordinary financial ties — Musk invested approximately $300 million to help elect Trump, and his companies have received over $15.4 billion in government contracts.

Although recent reports suggest Mr. Musk may soon leave his governmental position, this timing — occurring immediately after receipt of Plaintiff’s demand letter — appears transparently strategic and does not negate the constitutional violations that have occurred while he exercises official authority. Moreover, Musk’s extraordinary government access will continue regardless of formal title, as evidenced by his: a) ongoing Top Secret security clearance, b) high-profile visits to the Pentagon, NSA, and CIA within a single month (March-April 2025), and c) documented back-channel communications with defense leadership.

The systematic suppression of Mr. Richards’ religious speech through sophisticated algorithmic techniques or manual censorship is not protected by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which only immunizes actions “voluntarily taken in good faith to restrict access to or availability of material.” X’s deceptive practices — publicly denying shadowbanning while simultaneously engaging in it — fail the statute’s explicit “good faith” requirement, especially when senior legal leadership explicitly denies the very practices the company is implementing.

Musk’s actions as both government official and platform owner also directly violate the January 20, 2025 Executive Order on “Restoring Freedom of Speech and Ending Federal Censorship,” which explicitly prohibits federal government officials from “engag[ing] in or facilitat[ing] any conduct that would unconstitutionally abridge the free speech of any American citizen.” As a Special Government Employee heading DOGE, Musk is bound by Section 3(a) of this Executive Order, which states that “No Federal department, agency, entity, officer, employee, or agent may act or use any Federal resources in a manner contrary to section 2 of this order.” His systematic suppression of Mr. Richards’ religious expression while simultaneously exercising governmental authority creates liability under both this Executive Order and the First Amendment.

The thing is, there really is a legitimate question here about whether government officials running social networks creates state action. It’s the kind of question that a law student could write an earnest paper about: “What if the government just… bought Facebook?”

But Richards’ complaint isn’t going to be the vehicle that answers it. For one thing, there’s a fundamental misunderstanding of Section 230 (conflating (c)(2)’s good faith provision with (c)(1)’s broader protections) suggests someone who skipped the basic reading. For another, there’s the small matter of claiming millions in damages from shadowbanning an account that admittedly never grew beyond 4,000 followers. And it’s barely worth mentioning the fact that there appears to be no local counsel on the complaint, which seems to violate the rules.

The complaint reads less like a serious constitutional challenge and more like the kind of thing you’d find pinned to a community center bulletin board in crayon. There are pages upon pages of conspiracy theories about everything from religious persecution to shadowy government psyops. Also, conspiracy theories about how content moderation works. It’s the kind of write-up that makes you wonder if maybe the shadowbanning wasn’t entirely algorithmic after all.

The judge assigned to the case, Brantley Starr — a Trump appointee and Ken Starr’s nephew — is less than impressed by Richards’ attempt to get a temporary restraining order.

On the present record, Richards does not meet the high standard for a temporary injunction. Richards must show that the “facts and law clearly favor” the injunctive relief. Richards argues that because the owner of X Corp., Elon Musk, took a temporary position as a special government employee, the platform is converted into a government forum, and thus subject to liability as a government actor. This is a novel argument, and far from clear in the terms of either controlling law or the facts in the record. It is clear that the law is not so overwhelmingly obvious that this Court should enter a mandatory injunction against X Corp. granting Richards ultimate relief at the outset of this litigation based on the current record. Therefore, the Court finds the application for a temporary restraining order should be DENIED WITHOUT PREJUDICE.

The judge’s dismissal is exactly what you’d expect for this particular complaint. But the underlying questions aren’t going away. At some point, courts are going to have to figure out when a government official’s control of a social media platform crosses the line into state action. And they’ll need to answer some pretty fundamental questions: Is there a meaningful distinction between Trump running Truth Social while President (which seems… not great?) and Musk running ExTwitter while reshaping federal agencies with wild abandon (which seems… also not great?)? Can private platforms maintain any real independence when their owners are literally writing executive orders about how the government should work?

These aren’t just fun law school hypotheticals anymore. They go to the heart of how we balance free speech rights in an era where government officials aren’t just trying to influence social media through stern emails and mean tweets — they’re actually buying, creating, and running the platforms themselves. We need a better case to test these theories. Preferably one that doesn’t include pages of conspiracy theories about psyops and religious persecution.

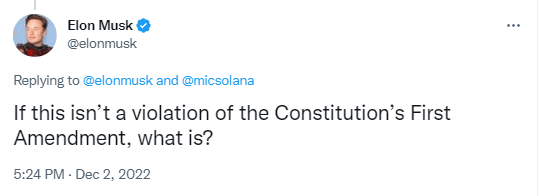

There’s one more layer of absurdity here worth exploring. Remember when Elon Musk insisted that the Biden campaign (not administration — this was before they took office) sending warnings about links with leaked Hunter Biden’s dick pics to Twitter was such egregious government interference that it must violate the First Amendment?

Just to be clear: A presidential campaign (not in power) alerting a private company about leaked intimate photos was, in Musk’s view, unconstitutional government censorship. But now that same Elon Musk is literally running both the government and what’s left of Twitter, and suddenly government control of social media seems… totally fine?

The voices that spent years screaming about government “censorship” whenever a White House staffer sent a mean email have gone mysteriously quiet now that their preferred officials aren’t just influencing social media companies — they’re running them from inside the government. It’s almost as if their constitutional principles extend only as far as their political preferences. This won’t shock anyone around here, but it still deserves to be called out explicitly.

Perhaps there’s a certain cosmic justice in watching the person who bought Twitter to “prevent government censorship” become, quite literally, the government doing the censoring. Though it would be nice if, at some point, the judicial system noticed.

Filed Under: brantley starr, donald trump, elon musk, section 230, shadowbanning, state action doctrine, state actor, thomas richards

Companies: twitter, x