Introduction

In the U.S., employers have an incentive to provide health insurance to workers because, unlike salary, these benefits are not subject to income and payroll taxes. That is why most workers have employer-sponsored coverage. However, because it is employers, rather than employees, who actually purchase the coverage, benefits often poorly fit the needs of specific workers and include features of little value to them. This increases costs, which imposes a substantial burden on firms and deters many small businesses from offering any coverage at all.

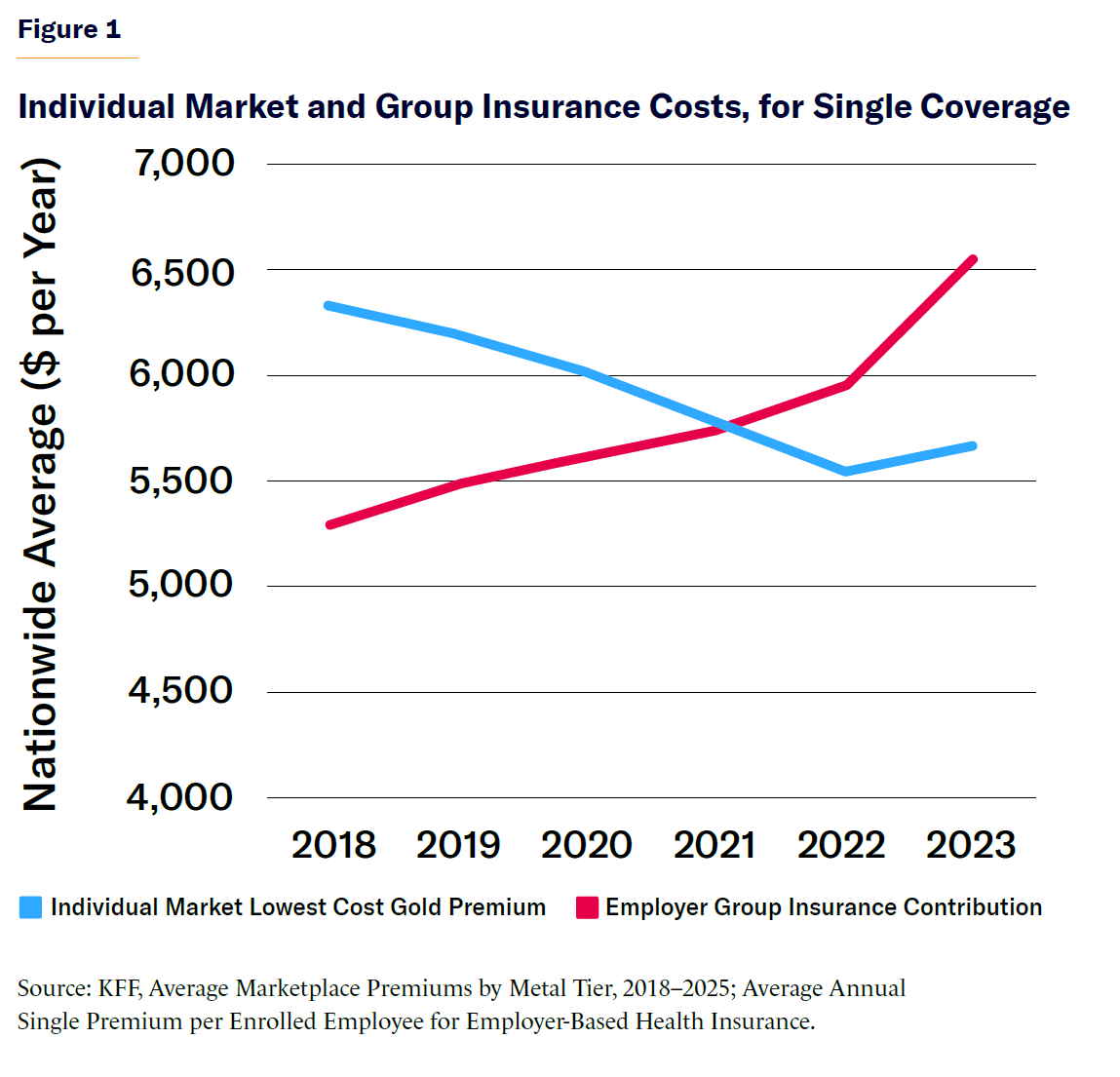

One possible solution to this problem was introduced in 2020: the Individual Coverage Health Reimbursement Arrangement (ICHRA), which allows a firm to provide tax-exempt funds for workers to buy their own health insurance. In theory, this should be an attractive option, since the cheapest individual market plans now cost, on average, 31% less than comparable employer-purchased health-insurance plans.

But very few firms currently offer ICHRA funds because federal regulations prohibit giving individual workers a choice between group health insurance and ICHRA. The concern is that, if firms were able to do so, they could effectively dump sicker workers on the individual market by degrading the quality of traditional benefits.

There is a less draconian way to prevent that from happening: employers should be allowed to offer workers a choice between both options, so long as their ICHRA contributions exceed minimum standards and their group plans conform to the same benefit requirements as those for the individual market.

In 2023, 117 million adults aged 19–64 were covered by employer-sponsored group health plans, while only 16 million obtained coverage through the individual market.[1] Some 75% of workers were offered employer-sponsored insurance (ESI), and 48% of workers opted to participate in it.[2] And 90% of firms that offered health benefits also covered employees’ dependents.[3] For single adults, premiums averaged $8,951, of which employers contributed $7,584 in worker compensation.[4]

In 2002, the Internal Revenue Service officially recognized the right of employers to use pretax funds to compensate employees and their dependents for out-of-pocket medical expenses with Health Reimbursement Arrangements (HRAs).[5] Unlike a Health Savings Account, HRA funds remain the property of the firm and typically don’t roll over from year to year, but HRAs allow employers to reimburse medical expenditures up to a set annual limit.

Initially, HRA funds could be used only for out-of-pocket expenses associated with group health plans and could not be used for the purchase of health insurance from the individual market. Policymakers feared that, if employers could offer uniform defined contributions via an HRA for workers to purchase their own plans, healthier workers would opt out of group coverage in favor of cheaper individual plans. That would leave employer risk pools disproportionately filled with sicker enrollees, for which remaining funding might be inadequate—leaving high-risk employees without options for affordable, quality coverage.

This became less of a concern after the Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA), which required that individual market health-insurance plans be sold at the same price to all seeking to enroll, regardless of medical risks (with a few specified exceptions).

In 2016, the 21st Century Cures Act established Qualified Small Employer HRAs (QSEHRAs). These allow small employers that do not offer health insurance to contribute tax-exempt funds for employees to purchase coverage on the ACA-regulated individual market. QSEHRA contributions must be provided on the same terms to all employees. In 2025, firms with fewer than 50 full-time employees could contribute up to $6,350 for single coverage and $12,800 for family plans.[6] If insurance on the individual market is not “affordable”—meaning that, after employer QSEHRA contributions, the premiums for silver-tier coverage are less than 9.02% of an employee’s income—workers may also claim federal Advance Premium Tax Credit (APTC) subsidies to assist with the purchase of plans.[7]

In October 2017, Trump issued an executive order aimed at expanding “employers’ ability to offer HRAs to their employees” and “to allow HRAs to be used in conjunction with nongroup coverage.” This led to a June 2019 rule establishing Individual Coverage HRAs (ICHRAs), which took effect in 2020.[8] ICHRA allowed all employers, regardless of size, to compensate workers through HRAs for expenditures to purchase health-insurance plans from the individual market regulated by ACA.

There is no minimum or maximum contribution that employers may make to ICHRAs. But employers with 50 or more full-time employees may be subject to the “employer mandate” penalty if they fail to directly provide “affordable” employer-sponsored insurance or ICHRA contributions to at least 95% of workers and one of those employees claims federal APTC subsidies. Unlike QSEHRA recipients, workers who receive an offer of ICHRA funds that makes individual market insurance coverage “affordable” are not eligible for federal APTC subsidies. Workers who receive an offer of ICHRA funds that still leaves individual market plans “unaffordable” must opt out of receiving any ICHRA funds in order to obtain APTC subsidies.

Employers may vary ICHRA contributions according to the age of workers (up to a 3-to-1 ratio) and their number of dependents but must otherwise provide benefits on the same terms to all workers within 11 permitted “classes” of employment.[9] Employers must offer either group coverage or ICHRA contributions to workers within a class; they are not permitted to allow individual employees to choose between group and ICHRA benefits. Nor are individual workers allowed to opt out of ICHRA benefits to obtain higher pay.

But some choices are protected. Employers cannot require that ICHRA funds be used only for specific insurance plans or steer workers to any particular option on the individual market. Workers may use any ICHRA funds remaining, after paying premiums, to cover out-of-pocket medical expenses.

The 2019 final rule projected that, by 2024, 11 million Americans would be enrolled in ICHRA plans.[10] In reality, the number is likely far lower; the HRA trade association estimates that only half a million people received either ICHRA or QSEHRA funds in 2024.[11] A survey for the National Federation of Independent Business found that 72% of small-business leaders said that they were “not at all familiar” with ICHRAs.[12]

But the ICHRA market is still expected to grow rapidly—and many hope that it will emulate the trajectory of 401(k) defined-contribution pensions, which grew from 8% of private-sector workers in 1980 to 47% in 2018.[13] Some 9% of firms currently offering health-care benefits and 20% of those not offering benefits said that they were likely to offer ICHRA in the next two years.[14] Insurance market analysts at Mark Farrah Associates have noted a recent shift from employer group to individual coverage, which they attribute in substantial part to ICHRA.[15]

Thatch, Stretch Dollar, Venteur, and a host of other firms have attracted venture-capital funding to expand into the ICHRA market.[16] For some major insurers, ICHRA is now a core part of their business strategy: Oscar Health has said that “ICHRA’s time has come,” while Centene called it “the future of health insurance for working Americans.”[17]

The Merits of ICHRA

When workers buy their own health insurance, as they do with ICHRA, they can choose plans that better fit their individual needs, thus reducing unnecessary costs and relieving a burden on employers.

Better suited to individual needs

Americans want more control over their health-insurance coverage. But employer-sponsored insurance does not empower individual consumers the way capitalism usually does. Benefit arrangements, premiums, networks, and cost-sharing structures are typically imposed by employers, with little or no say from employees. Annual benefits meetings come as an unpleasant surprise to many workers, who have only just gotten used to their health-care plans, only to have them disrupted. A 2019 poll found that 70% of employees thought that firms should not be allowed to change or eliminate health-insurance plans against workers’ wishes.[18]

To minimize moral hazard and adverse selection and to keep administrative costs down, firms typically give workers limited choice when it comes to health insurance. Most employees can select from only a few similar plans, generally from the same insurer. For 40% of workers and 67% of those employed by small businesses, only one plan is available.[19]

On the individual market, by contrast, the average consumer in 2023 could choose from 88 plans from five different insurers.[20] Plans are therefore available offering very different covered benefits, provider networks, and levels of cost-sharing. This allows enrollees select plans that fit their households’ specific needs. These choices are potentially valuable. According to a 2010 study, workers would willingly forgo 10%–40% of the funds that their employers pay for their health insurance in exchange for control of the choice of their health-insurance plan.[21]

Reducing health-insurance costs

With employer-sponsored health insurance, workers typically resist cost controls—such as cheaper provider networks, utilization controls, or cost-sharing—because they directly bear the inconvenience, while associated savings are perceived as accruing to the firm. But when individuals purchase their own coverage, health-insurance consumers are far more sensitive to price. A 1% increase in premiums leads to a roughly 0.5% drop in enrollment in employer-sponsored plans—but a 1.7% decline in individual market plans.[22]

One-size-fits-all group coverage makes it especially difficult to offer narrow provider networks, which are the most effective constraint on the growth of hospital costs. Limited networks are usually not a problem for individuals, who mainly care about access to their own doctor, local hospital, and a few other preferred providers. Employers, however, must satisfy workers in many different neighborhoods, each of whom insists on access to very different sets of medical providers. That makes it difficult for group plans to negotiate better rates by threatening to leave the costliest hospital systems out of their networks.[23]

The lower cost of health care provided by individual market plans has, until recently, been offset by the greater medical needs of those who enroll in them—and, thus, premiums were higher because the average person in the pool needed more care. In 2020, a study for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) found that, after adjusting for a 20% higher level of medical need among individual market enrollees, their health-care costs were 27% lower than those in large employer group plans.[24]

But as the individual market has stabilized, it has attracted a more balanced risk pool, and premiums have declined substantially—even as the cost of group coverage has steadily increased.

A comparison of employer contributions to group health insurance with premiums for similar coverage on the individual market shows that the latter now offers a better deal.[25]

Gold-tier individual market plans cover 80% of medical expenses—similar to employer-sponsored plans. Deductibles on the individual market averaged $1,450 in 2022, while those on employer-sponsored plans averaged $1,600.[26] In 2018, the cheapest gold-tier individual market plans cost an average of $1,024, or 19%, more per year than employer contributions to group plans. By 2023, these plans were costing $878, or 13%, less than employer contributions (Figure 1).

When factoring in the average $1,640 employee contribution to group-plan premiums, individual market coverage in 2023 cost $2,518 less overall—a 31% savings versus employer-sponsored plans.[27]

In 2024, the average employer ICHRA contribution was $6,504—roughly in line with average employer contribution to group insurance from the previous year. Among ICHRA recipients, 30% chose gold-tier insurance, while the majority opted for lower premiums by accepting higher cost-sharing than is typical in group plans. A total of 39% enrolled in silver-tier and 31% in bronze-tier plans. (Gold-tier plans cover 80% of medical expenses, silver 70%, and bronze 60%.)[28]

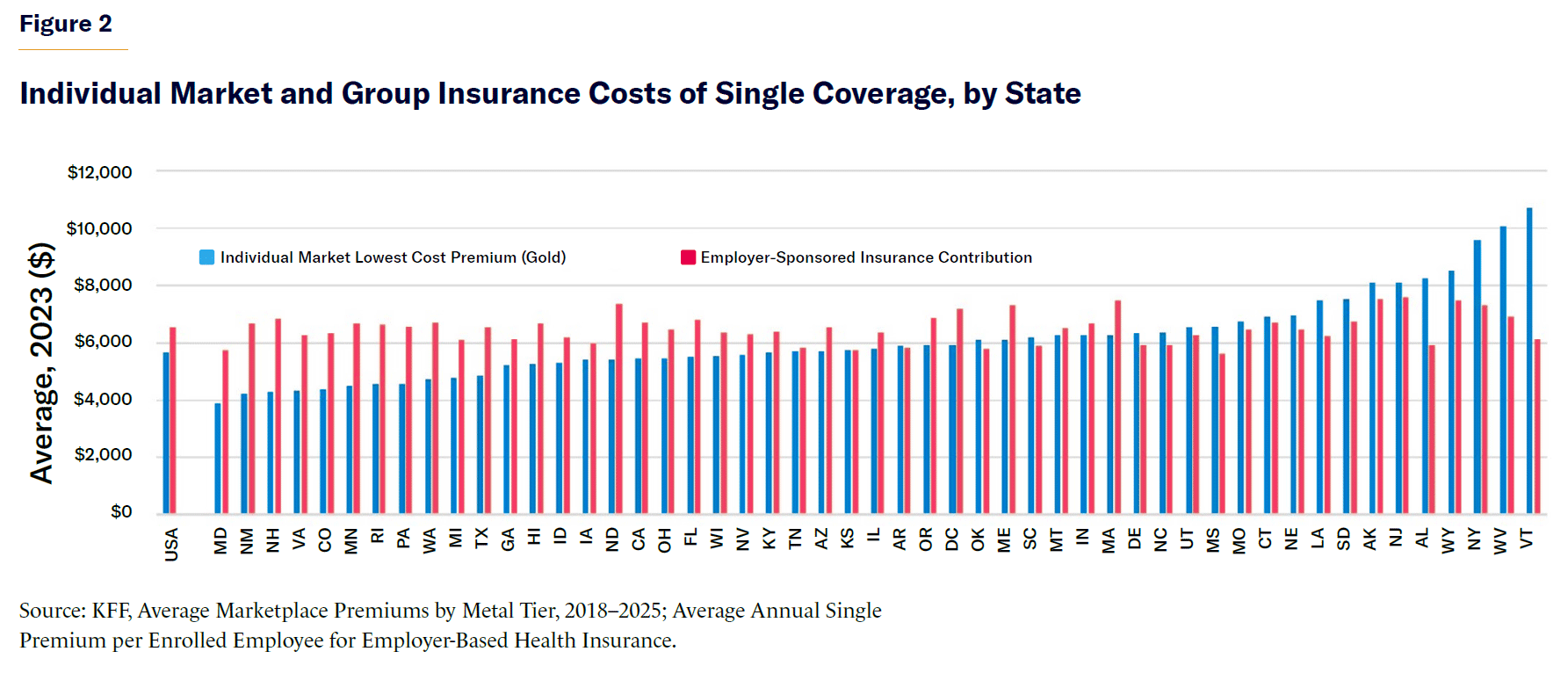

The number of states where average employer health-insurance contributions exceed gold-tier individual market premiums has increased, from 10 in 2018 to 32 in 2023 (Figure 2). In some areas, the potential savings are now very large. For instance, in Putnam County, Ohio, the cheapest gold-tier premium on the individual market would cost only $7,728 per year, compared with $15,552 through the small group market.[29]

Most of the decline in individual market premiums occurred before Congress expanded APTC subsidies through the American Rescue Plan Act and Inflation Reduction Act. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that, if those expansions are allowed to expire, unsubsidized individual market premiums would increase by only 8% ($450 per year for gold-tier plans).[30] But that could also be offset by the proposed elimination of regulations, which the Department of Health and Human Services estimates increased unsubsidized premiums by 9%.[31]

Reducing the burden on employers

Health-care costs are a growing burden on employers across the economy. Starbucks spends more on health care for its workers than it does on coffee.[32] By allowing staff to purchase coverage more cheaply from the individual market, ICHRAs can help reduce these expenses. Their defined-contribution structure also makes health-care spending more predictable and easier to manage—much like the shift to 401(k)s did for retirement benefits.

Allowing employees to purchase their own health insurance also reduces the burden of managing health benefits to firms—freeing them to focus on their core business, rather than on navigating the complexities of health-care administration. Depositing funds into an HRA is far easier and faster than negotiating complex benefit packages with insurers, handling claims disputes, and ensuring compliance with detailed benefit regulations.[33] It also eliminates the need to satisfy employees with widely varying preferences for medical providers and reduces reliance on insurance brokers, whose incentives are often distorted by commissions from insurers and resulting conflicts of interest.

This approach can help more small businesses to offer health insurance by protecting them from a few catastrophic claims or the financial risk of employing sicker workers—both of which can substantially drive up group-rated premiums. In 2024, 91% of workers (both full-time and part-time) in firms with more than 500 workers received an offer of employer-sponsored insurance, while only 56% of those with fewer than 50 workers did.[34] The more health-insurance costs are reduced, the more workers firms will be able to cover.

Fit for the modern workforce

ICHRA can also help large employers, by making it easier for them to satisfy a broader diversity of workers’ health-care needs. The defined-contribution structure is especially useful for firms with workers scattered across many states—as is increasingly common in the era of remote work. Even small businesses may now have staff distributed nationwide but lack the infrastructure to administer or finance group plans across different state insurance regimes.

ICHRAs also help extend coverage to part-time workers who are often left out of traditional employer-sponsored insurance. In 2024, 89% of full-time workers received an offer of employer-sponsored health insurance, compared with only 26% of part-time workers.[35] By allowing multiple employers to make partial, tax-exempt contributions, ICHRAs offer a way for these workers to obtain coverage.

ICHRAs are a better fit for fragmented employment careers. The median job tenure is less than four years.[36] ICHRAs allow workers to maintain coverage and access to their doctors even as they move from job to job, thus allowing workers to move to jobs for which they are better suited, without risking a lapse in insurance coverage.[37]

Spillover benefits and fiscal savings

A shift from employer-sponsored group plans to ICHRAs would benefit those who are neither enrolled nor directly paying for them.

Because individual market plans allow insurers to steer patients to cost-effective medical providers, a shift toward them would deter the hospital industry from needlessly inflating costs. Such a dynamic has been demonstrated in the rise of Medicare Advantage, where cost-sensitive plans have helped reduce hospital costs even for patients covered by other insurers.[38] A broader shift away from one-size-fits-all group insurance and provider networks toward defined-contribution support for insurance would likely also deter policymakers from imposing costly benefit mandates on plans.

Lower health-insurance costs would help trim the federal deficit by reducing the cost of APTC subsidies and the employer-sponsored insurance tax exemption.[39] The budgetary cost of APTC subsidies would be further reduced if ICHRAs enable firms to offer “affordable” health insurance to more workers.

A full transition from group to individual market coverage would improve the individual market risk pool, further lowering unsubsidized market premiums.[40] This, in turn, would further reduce the cost of APTC subsidies.

Reform Proposal: Worker’s Choice ICHRA

So what is holding ICHRAs back? Why are so few firms taking advantage of them to fund employees’ health insurance?

The main barrier is a federal regulation that prevents employers from offering workers ICHRA benefits, unless they force all employees within permitted classes to switch from group to ICHRA benefits. Adopting ICHRAs is an all-or-nothing proposition: to offer them to any workers, a firm must withdraw group coverage from all employees in that class—risking a backlash from staff who prize features of their current benefits. That makes it a big leap for human-resources departments and a tough sell to businesses.

The regulatory prohibition on “offering employees within a class of employees a choice between a traditional group health plan and an individual coverage HRA” was intended “to prevent a plan sponsor from intentionally or unintentionally, directly or indirectly, steering any participants or dependents with adverse health factors away from the plan sponsor’s traditional group health plan and into the individual market.”[41]

Originally, this was a reasonable precaution, given the uncertainty surrounding the rollout of ICHRAs. But with more experience, it is now possible to replace that blanket prohibition with more precise regulatory guardrails to mitigate the dumping of sicker patients on the individual market without severely impeding adoption of ICHRAs. Such reforms have been endorsed, in general terms, by the Bipartisan Policy Center.[42]

The initial regulation establishing ICHRA acknowledged that allowing small businesses to offer employees the choice between group coverage and ICHRA would pose little risk of adverse selection, thanks to existing community rating and benefit regulations in the small-group market. This option was prohibited only to reduce administrative complexity for exchanges and insurers. But regulators acknowledged that they may eliminate the prohibition in the future.[43] They should now do so.

Federal regulations should be revised to establish a new Worker’s Choice ICHRA (WCICHRA). These arrangements would allow larger employers to offer individual workers the choice of group coverage or ICHRA contributions, provided that the following conditions are met:

- The employer’s group plan must be “affordable,” as defined in ACA, for all workers in the employment class offered a choice.

- The group plan complies with individual market rules for:

- Essential health benefits (as specified by ACA)

- Limits on out-of-pocket costs (as specified by ACA)

- Regulations on prior authorization and appeals (as specified by CMS)

- Network adequacy requirements (according to state regulations)

- The employer’s contributions to Worker’s Choice ICHRA must:

- Constitute an offer of “affordable” health insurance (as specified by ACA’s “employer firewall” regulation) for all workers within an employment class offered health insurance.Be adjusted by age, in proportion to the age-rating of premiums in the lowest-cost gold- plan available.[44]

- Vary by county, in proportion to the premium of the lowest-cost gold-tier plan available.

These proposed regulations would suffice to prevent firms from employing Worker’s Choice ICHRAs to degrade or otherwise manipulate group health plans for the purpose of dumping sicker workers on the individual market, due to their interaction with:

- Existing regulations requiring nondiscrimination in the provision of health-care benefits to staff.

- Existing regulations restricting permissible tax-exempt health-care benefits to qualified medical expenses.

- Employers’ desire to provide tax-exempt compensation to attract, retain, and maintain good relations with valued workers.

The proposed regulations would deter employers from setting WCICHRA contributions to selectively qualify lower-income workers for federal exchange subsidies. They would help protect older workers from the higher cost of individual market premiums.[45]

As under current ICHRA rules, employers would be allowed to offer additional WCICHRA contributions to fund the purchase of insurance for dependents or to cover out-of-pocket costs for qualified medical expenses.

Conclusion

Employer-purchased health insurance does a poor job of meeting the diverse needs of individual workers and their families, which inflates the cost of plans. ICHRAs can help solve that problem by allowing workers to purchase their own health insurance with pretax funds from their employers.

It has often been assumed that ICHRA plans would be unappealing to most firms, due to the higher cost of non-group coverage. But individual market plans are now available in most states for substantially less than the cost of equivalent group coverage.

The adoption of ICHRAs has been stymied because federal regulation makes choosing them an all-or-nothing proposition. Employers cannot offer employees a choice between an ICHRA and their current plan.

Some regulations are necessary to prevent employers from designing health-care benefits to dump workers with costlier medical needs on the individual market, but existing rules are needlessly restrictive. Instead, ICHRA regulations should be modified to let firms give workers a choice between group or ICHRA health-insurance benefits, so long as their ICHRA contributions exceed minimum standards and their group plans conform to benefit regulations for individual market plans.

Endnotes

Photo: miodrag ignjatovic / E+ via Getty Images

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).