This weekend marks the second of two major festivals in the Islamic calendar—Eid al-Adha—and it’s one whose basis many Jews and Christians will be familiar with: Abraham’s binding of Isaac. Dispatch Contributing Writer Mustafa Akyol explains how some Islamic understandings of the episode differ from Jewish and Christian understandings, and how classical Western philosophers have understood it.

And in this week’s “Quick Questions” segment, I posed some questions to David S. Dockery, president of the Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, about this week’s annual meeting of the Southern Baptist Convention.

Mustafa Akyol: Why Are Billions of Muslims Celebrating the ‘Feast of Sacrifice’?

This weekend, while most Americans may not even notice, over 2 billion Muslims around the world are celebrating one of the two major religious festivals of the year: Eid al-Adha, or the “Feast of Sacrifice.” It is a three-to-four-day event that marks an official holiday in most Muslim-majority countries. It also aligns with the culmination of the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca, performed by around 2 million visitors every year to Saudi Arabia.

The feast, which begins on the 10th day of Dhu al-Hijjah, the 12th month of the Islamic lunar calendar, typically starts with morning prayers in a mosque, followed by families getting together. Children receive gifts, such as new clothes and shoes—something they may have waited for all year, as I recall from my own childhood. Meanwhile, men of the house take care of the ritual from which the very name of the festival comes: the sacrifice of an animal—such as sheep, goats, or cows—following specific Islamic guidelines. The meat is divided into three parts: one for the family, one for relatives and friends, and one for the poor, emphasizing charity and community.

The very act of sacrifice, slaughtering an animal, can be controversial—and there is indeed a movement to ban any such ritual slaughter in Europe and in the U.K., which has alarmed both Jews and Muslims, whose kosher and halal meat traditions are very similar. In response to those who advocate a ban, one could at least say that both traditions have rules that minimize animal suffering. In Islam, the Prophet Muhammad commanded, “Spare suffering to the animal you slaughter,” and jurists developed procedures: The animal must be handled gently, it should not see others slaughtered before itself, the cut should be immediate, the pain minimal.

So if ritual sacrifice is a part of the Islamic tradition, just like the Judaic one, some may still wonder why it is also the central theme of a major Islamic festival.

The answer, as explicitly affirmed in Islamic sources, is found in an ancient religious narrative: the story of Abraham receiving a divine command to sacrifice his son, only to sacrifice a lamb instead, miraculously provided at the last moment by the merciful God.

This story is biblical, as most Jews and Christians would immediately recognize. It is also quranic, as the Islamic scripture often retells biblical stories, sometimes with subtle nuances but still conveying similar messages. Among these are the stories of Abraham, who is praised in the Islamic tradition as Khalil-Allah, or “the friend of God,” and the pioneering monotheist that all believers—Jewish, Christian, or Muslim—should emulate. The Quran, in fact, presents itself as the rebirth of Abrahamic monotheism in pagan Arabia, bringing idolatrous Arabs back to the “God of Abraham, Ishmael, and Isaac” that their Jewish cousins had always worshipped. (Q 2:133)

Regarding the sacrifice story, the Quran narrates a concise version of it in its chapter 37, “As-Saffat.” Here Abraham first prays to God for a righteous heir and soon gets the “tidings of a gentle son.” But then a drama unfolds:

When the boy was old enough to work with his father, Abraham said, “My son, I have seen myself sacrificing you in a dream. What do you think?” He said, “Father, do as you are commanded and, God willing, you will find me steadfast.”

When they had both submitted to God, and he had laid his son down on the side of his face, We called out to him, “Abraham, you have fulfilled the dream.” This is how We reward those who do good; it was a test to prove.

We ransomed his son with a momentous sacrifice, and We let him be praised by succeeding generations: “Peace be upon Abraham!” (Q 37: 102-109)

So, those “succeeding generations” include today’s Muslims, who remember Abraham, his son, and their ordeal, by emulating them literally, every year, in the Feast of Sacrifice.

Who was that son, exactly? Interestingly, the Quran never names him. That is why some early Muslim commentators, influenced by the biblical tradition—which Muslims embraced as Israilliyat, or “of the Israelites”—identified the son as Isaac. However, a later and eventually dominant interpretation in Islamic exegesis came to identify the son as Ishmael. It is a shift that seems to align with the broader historical narrative in which Jews trace their lineage to Isaac, while Arabs traditionally see themselves as descendants of Ishmael. So, giving the latter the central role in this story may have made sense to Muslim exegetes.

Meanwhile, there is an ethical challenge presented by this story to both Jews and Muslims, as well as Christians, all of whom honor Abraham. It is, flatly speaking, a chilling account of a father deciding to kill his beloved son with his bare hands. If something like this happened anywhere in the world today, we would consider it an act of insane savagery, if not pure evil. So, how can we make sense of the fact that it was attempted by none other than a great prophet, following a divine command, and worthy of praise in the scriptures?

This has been a daunting question for theologians from all three Abrahamic traditions. The most common explanation is that God, of course, would never allow the slaughter of an innocent child—He just wanted to test Abraham’s faith. Abraham, for his part, would of course never hurt his beloved child—but he put his faith in God, and hoped that there must be something good at the end. Some theologians—such as Jewish studies scholar Jon D. Levenson, as he argued in his 1993 book, The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son—also suggest that the story was actually a symbolic rejection of the child sacrifice traditions that existed in some ancient Near Eastern cultures. Christians, meanwhile, have interpreted the sacrifice story as foreshadowing of Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection.

While all these explanations may have merit, the sacrifice story still leaves us with an important question: Was Abraham’s blind obedience to a divine command, as chilling as it is, an exemplary act of piety?

For Søren Kierkegaard, the prominent Danish Christian theologian, the answer was yes. In his seminal 1843 book, Fear and Trembling, he portrayed Abraham’s obedience as the epitome of faith. Rational ethics would require disobedience, Kierkegaard noted, but Abraham opted for a “teleological suspension of the ethical.” This made him a hero of religion, a “knight of faith.”

However, for Immanuel Kant, the eminent philosopher of the German Enlightenment, there was nothing too admirable about such blind faith. In his influential 1793 work, Religion Within the Boundaries of Bare Reason, Kant referred to the sacrifice story only as a lesson against the dangers of blind obedience. Religious commandments should conform to universal ethical norms, he argued, or otherwise:

If something is represented as commanded by God in a direct manifestation of him yet is directly in conflict with morality, it cannot be a divine miracle despite every appearance of being one (e.g., if a father were ordered to kill his son who, so far as he knows, is totally innocent).

Kant arguably had a point, because “suspension of the ethical,” just to obey some higher authority, can lead to horrific results—both in religious and secular worldviews. In the religious ones, as Kant observed, it can create monsters like “the Grand Inquisitor,” and all kinds of religious zealots, who strive to “raze all unbelievers from the face of the earth.” In secular worldviews, as we have seen after Kant, blind obedience can create fascist, communist, or nationalist apparatchiks, who kill and torture to serve the great leader, the revolutionary party, or the glorious nation.

But is there a way to align the Kantian insight—the primacy of rational ethics over authoritative commands—with the story of Abraham’s sacrifice? At first glance, this seems challenging, as both the Bible and the Quran appear to commend Abraham’s obedience to a morally troubling divine command. Therefore, the story seems to affirm what philosophers call “divine command theory”—the view that divine commands create ethical norms, rather than conforming to them.

However, in the Islamic tradition, there is a little-known interpretation of the story that offers a different answer. It was first suggested by Mu’tazilites such as the early 11th century theologian Qadi Abd al-Jabbar, who are called the “rationalists” of Islamic theology, as they believed that ethical norms of “right” and “wrong” are inherent in the nature of things, rationally discoverable, and independent of divine revelation. This view led them to grapple with the sacrifice narrative, proposing an alternative interpretation that was later embraced by others, including the prominent Sufi scholar Ibn al-Arabi, some 200 years later.

This alternative interpretation rests on a remarkable detail of the quranic version of the sacrifice story quoted above. Here, unlike in the Bible, Abraham never receives an explicit commandment from God to slaughter his son. Instead, he only sees a dream in which he does that, which he interprets as a divine command. But was that really the right interpretation? “How could it be a command from Allah,” al-Jabbar asked, as “he could see anything in his dreams?” So, perhaps Abraham had just misinterpreted the dream’s lesson, but God rescued him from “Abraham’s misapprehension,” as Ibn al-Arabi wrote. Abraham was still praiseworthy for his sincerity, but God had never commanded the terrible act.

In other words, one could still praise Abraham and uphold ethical rationalism. One could be both Abrahamic and Kantian.

To be frank, such theological ruminations may not be on the mind of every believer who will be celebrating the Eid al-Adha this weekend. But they remind us of the richness and the complexity of the theological traditions built on the footsteps of Abraham.

His sacrifice story also reminds us how the three great religions that venerate him—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—are deeply connected. They are all truly Abrahamic creeds—with all the blessings, and the challenges, that come with the enduring legacy of that great man.

Quick Questions

Beginning today, messengers for the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC)—the country’s largest Protestant denomination—will gather in Dallas for their annual meeting. Recent years have seen consternation over the SBC’s handling of widespread abuse allegations among pastors, the denomination’s financial strain caused by responses to those abuse allegations,votes on the role of women in ministry, and the future of the denomination’s public policy advocacy arm—the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission.

To get an understanding of what to expect this week, I corresponded with David Dockery, president of the Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary. He’s led multiple Christian institutions of higher education and is generally regarded as a statesman of the Southern Baptist Convention. My questions to him are in bold, and some of what follows has been edited for clarity.

In recent years, responding to abuse allegations and clarifying the denomination’s position on the role of women in ministry have been the most widely discussed topics to come from the annual meeting. To what degree do you think those two topics will be so again?

These two issues will once again be topics of conversation as has recently been the case, but I do not expect them to be the primary topics of conversation at the 2025 SBC. There will be updates from the SBC’s Executive Committee related to the handling of abuse allegations. Many people for the first time will hear from Jeff Dalrymple, the new director of abuse prevention and response, who has given much thought to how to best guide the SBC’s responses to these important matters in the future.

As for the role of women in church, worship, and ministry, there will likely be a request for the convention to once again consider a proposal very similar to the so-called “Law/Sanchez Amendment,” which addresses the role of women and the ministry office of pastor/elder/overseer. The amendment failed to pass by the necessary percentage of votes this past year, but it could very well find more support this year.

In your view, what issue or topic is not (now) or will not (during/after the annual meeting) get enough attention from SBC members and/or media?

There is a wonderful opportunity at this year’s meeting for the SBC to recommit itself anew to the Cooperative Program, the convention’s voluntary funding mechanism, as we celebrate the 100th anniversary of this brilliant approach to funding ministry from the local churches to and through the state conventions and the various ministries of the national convention, including the mission boards, seminaries, and other entities. It will be a shame if we treat this moment only as a time of historical recognition and miss the moment to reprioritize our overall commitment to cooperation and to the generous support of ministry priorities, such as evangelism, missions, ministerial preparation, and benevolence causes—those things that help to bring and hold us together. By strengthening our commitments to the Cooperative Program, churches across the SBC will be able to multiply their efforts, doing more together with a unity of purpose than they could ever do alone.

Generally, is the SBC more divided now than it was five years ago or less so? Why?

From the 1970s to the late 1990s, the primary issue of debate within the SBC focused on the truthfulness and authority of Holy Scripture and the uniqueness of the gospel. Then, in this century, the issues seemed to become more narrowly focused on matters such as Calvinism, the implications of an affirmation of the sufficiency of Scripture, and the role of women in ministry, among other matters. It sometimes seems that as the issues have become more focused, the rhetoric has become more heated. Yet, in God’s providence, Southern Baptists have often been able, over time, to work through the disagreements and find ways to cooperate together.

Some years seem to surface more issues than in other years. I think it is true that there are various and multiple issues that will likely be considered at this year’s convention, including the Business and Financial Plan, the future of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, and perhaps other matters. We pray that we will be able to process these matters well in a way that will provide helpful information for the messengers so that they, with the help of God’s Spirit, will be able to make good and wise decisions for the future of the SBC. We pray that the Lord will be glorified in the way that the discussions take place on the floor of the convention.

What issues/topics do you believe will get more attention from messengers and leaders (not outsiders/media) at this annual meeting and why?

As I have noted, I think the Business and Financial Plan, regarding how Cooperative Program funds are stewarded by those who are recipients of these generous offerings, will be one of the primary topics of discussion at this year’s gathering. There will be ongoing calls for more transparency in reporting and more careful oversight of the various entities.

This year’s meeting is distinctive because it is the 100th anniversary of the Baptist Faith and Message, the SBC’s confessional statement, and the Cooperative Program, both having been adopted at the historic 1925 Convention.

We pray that we will give attention to what it means to be both confessional and cooperative, convictional and charitable. We need wholehearted “both/and” responses to these things and not imbalanced “either/or” choices. To only emphasize cooperation can open the door to compromise while focusing only on conviction can sometimes lead to shrill voices and a cantankerous spirit. We pray that as the convention processes the proposed motions and amendments, that they will do so with this both/and approach, which will help promote both a commitment to Christian truth and a spirit of Christian unity.

According to recent data, membership in the SBC is at a 50-year low, but baptisms are up 10 percent from last year. How ought the denomination navigate that tension? Do you anticipate conversations at the annual meeting playing out any particular way regarding these data points?

These two statistics point to two different trends in our midst. The membership numbers, it seems to me, are quite problematic. Some say that there has been renewed attention to cleaning up the membership rolls at local churches. I hope this is the case, but it seems more likely to me that the expanding influence of secularism and the rise of the religiously unaffiliated are making inroads into the churches, resulting in decline of commitment and a loss of a sense of belonging and its importance.

On the other hand, some in our society have found that this “secular age,” to borrow a phrase from Charles Taylor, has left people empty and wanting something more. Thus, there seems to be a new openness to the good news of the gospel of Jesus Christ, especially on college campuses. In addition, I believe that many individuals and churches across the SBC have also recommitted themselves to the priority of evangelism and the combination of these factors has led to an increase in baptisms, which we pray will continue. Still, I think the membership decline points to the reality of many unhealthy churches, which will result in an unhealthy denomination. We pray for a genuine renewal to take place across the SBC in the days to come.

One of the big issues this year will likely be the future of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission. Are you pleased with how conversations over the ERLC’s future have taken place leading up to the annual meeting? Do you think fellow Southern Baptists are handling those debates the right way?

When we have had serious debates and divisions about key topics or programs in the past, it has often been helpful to invite a smaller group to study these matters in more depth and then report back to the convention within a prescribed time period. A few years back, I was asked to serve as the chairman for a task team to address the debates over Calvinism. Likewise, I served on a study group to respond to the calls that were surfacing at that time to change the name of the Southern Baptist Convention.

Both initiatives led to a sense of consensus that helped to bring more light and less heat to these issues so that we could move forward without being sidetracked by the rhetoric. Randy Davis, the state convention leader among Tennessee Baptists, has proposed that such a course be adopted at this year’s convention. I think that his wise proposal would allow a smaller group to study the matter in depth rather than to see who can line up the most influential voices to speak for or against these matters on the floor of the convention, resulting in a hurried decision.

I think the messengers are growing weary of hearing calls for the defunding of the ERLC each year. It seems time to decide to recommit our support for the ERLC or to find another way for the SBC to carry out these ministry assignments for the good of the churches and the convention at-large. We trust the Lord to grant much wisdom in these important matters.

More Sunday Reads

- For the Associated Press, Foster Klug, Mari Yamaguchi, and Mayuko Ono report on Japan’s “Hidden Christians,” a small sect of Christianity that for centuries hid itself to escape persecution, and which is now dying off.“Little about the icons in the tiny, easy-to-miss room can be linked directly to Christianity — and that’s the point. After emerging from cloistered isolation in 1865, following more than 200 years of violent harassment by Japan’s insular warlord rulers, many of the formerly underground Christians converted to mainstream Catholicism. Some, however, continued to practice not the religion that 16th century foreign missionaries originally taught them, but the idiosyncratic, difficult to detect version they’d nurtured during centuries of clandestine cat-and-mouse with a brutal regime. On Ikitsuki and other remote sections of Nagasaki prefecture, Hidden Christians still pray to these disguised objects. They still chant in a Latin that hasn’t been widely used in centuries. And they still cherish a religion that directly links them to a time of samurai, shoguns and martyred missionaries and believers. Now, though, the Hidden Christians are dying out, and there is growing certainty that their unique version of Christianity will die with them.”

- In The Atlantic, historian Molly Worthen writes on how charismatic faith of all stripes might be making a comeback. “Even as partisan politics have come to display the dynamics of fundamentalist sects, there are signs that the 60-year slide of organized religion in the West has slowed. And it might be starting a quiet recovery. After steadily rising for 20 years, the number of Americans who say they have no religious affiliation seems to have leveled off. More young men are going to church, and many of them are joining Catholic or Orthodox congregations. In England and Wales, Gen Z is leading a spike in church attendance, which has risen from 8 to 12 percent of the population in just six years. During my reporting, I kept meeting people who had grown tired of cynicism and DIY meaning-making and made their way into ancient institutions and supernatural faith.”

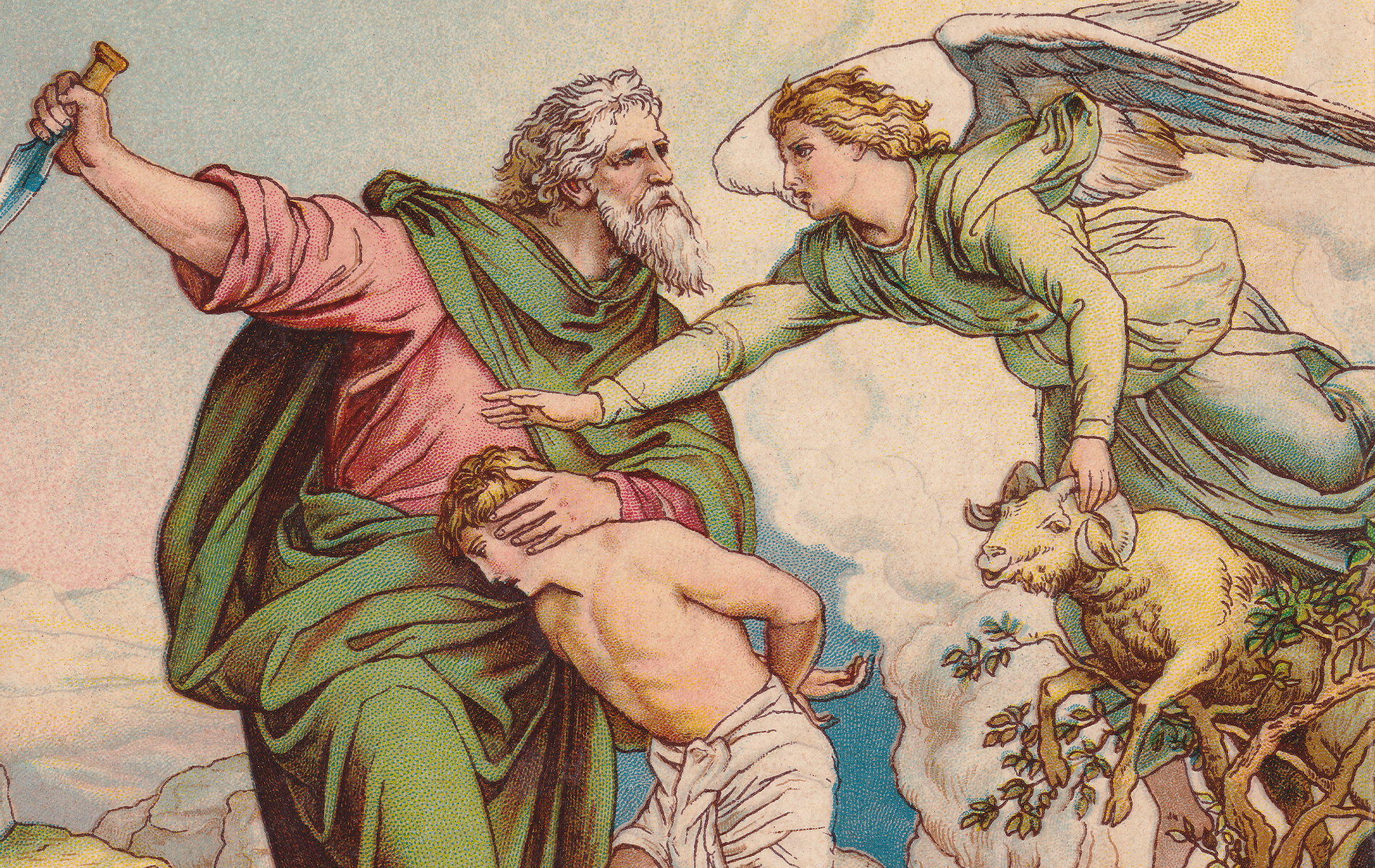

Religion in an Image