Executive Summary

The Veterans Affairs (VA) health-care system was developed to finance and deliver hospital care to servicemen injured in the world wars. Since the World War II era, the veteran share of the nation’s population has plummeted and shifted away from large northeastern cities. The VA, however, maintains almost the same 170 major hospitals. These facilities now treat only a third as many patients as similar-size private hospitals.

To prevent the VA system’s overhead costs from being concentrated on a shrinking number of patients, Congress has repeatedly expanded eligibility for VA care beyond the treatment of service-connected conditions. As a result, most treatment at VA hospitals is now for medical conditions similar to those treated in the private sector. Since VA hospitals are located far from where most veterans now live, Congress has also provided funding for them to receive medical services from private providers—and most VA-funded inpatient care is now delivered privately. Unfortunately, these changes have not been linked to a reduction in expenditures at VA hospitals. As a result, the cost of the VA program per veteran has increased more than ninefold since 2000.

Veterans injured in service of their country should receive convenient treatment at public expense. But in order to prevent taxpayers from being stuck with the full cost of maintaining large facilities serving a declining patient population, Congress should allow VA hospitals to treat privately insured patients who are not eligible for VA-funded care.

The Traditional VA System

The federal government funded hospitals to treat veterans long before Medicare, Medicaid, or private health insurance provided payment for health-care services.

In 1796, Congress distributed grants for the relief of sick and disabled merchant seamen, which led to the formation of the marine hospital system. During the nineteenth century, the number of such federal facilities along the coasts gradually expanded, and these were supplemented by nursing homes for Civil War veterans.[1]

The War Risk Insurance Act of 1914 entitled all honorably discharged disabled veterans to health care, but the few existing public hospitals would soon be overwhelmed by World War I. As 200,000 wounded veterans returned from Europe, Congress established a system of permanent federal hospitals across the country to treat them.[2] World War II increased the number of veterans from 5 million to 20 million, making 43% of adult males eligible for Veterans Affairs (VA) benefits.[3]

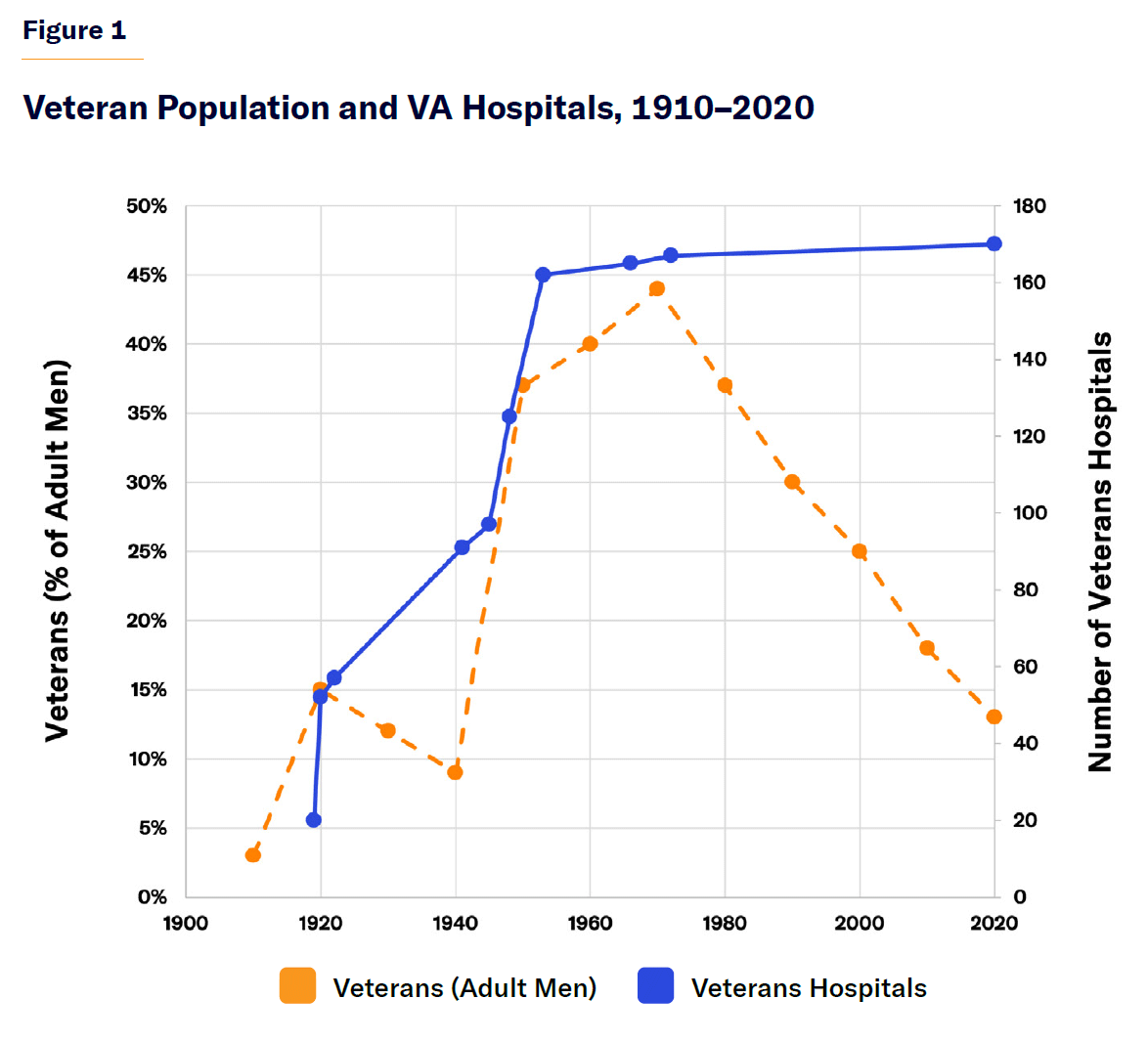

To accommodate those service members, Congress rapidly expanded the number of VA hospitals, from 56 in 1922, to 97 in 1945, and to 162 in 1953.[4] The VA still had 170 hospitals in 2020, despite the steady decline in the number of veterans to just 13% of the adult male population (Figure 1).[5]

VA health-care benefits differ fundamentally from Medicare or Medicaid because they do not confer a legally enforceable entitlement to care, with providers receiving payment for each medical service they deliver. Annual Medicare and Medicaid spending depends on the amount of covered services that are delivered to eligible beneficiaries, but VA health-care spending is fixed ex ante by Congress through annual appropriations. Thus, funding may run short when the demand for care is high, or expenditures can remain constant even when the amount of treatment delivered declines.

The VA distributes these funds among 18 regional Vertically Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) for them to deliver hospital, physician, prescription drug, and long-term-care services to eligible beneficiaries. VISNs may use these funds to provide additional services beyond the scope of typical health-care benefits, such as travel reimbursements, stipends for family caregivers, dental care, eyeglasses, alternative medicine, or assistance for homeless veterans. Funding is divided among VISNs according to the relative number of patients they have treated, adjusted by rough categories for the severity of medical needs.[7]

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) directly employs more than 371,000 health professionals at 170 medical centers and 1,138 outpatient sites, making it the largest health-care system in the United States.[8] In 2023 in the U.S., there were 18.3 million veterans, of whom 9.1 million were enrolled in VA’s health-care system and 6.3 million received treatment.[9] They made 131 million outpatient visits and underwent 1.1 million inpatient admissions to VA facilities.[10]

Veterans of full-time active duty without dishonorable discharge are eligible for benefits, but medical services may be withheld or subject to waiting lists. Access to care is officially prioritized: veterans with severe service-connected disabilities are given the highest priority, followed by those with lighter service disabilities, those with noncombat disabilities, those involved in specifically designated wars, those with low incomes, and other veterans. Just over half of enrollees are in the priority groups associated with service-connected disabilities (Table 1).[11] VA care for most beneficiaries is funded entirely by the federal government, but the beneficiaries in the lowest three priority groups (about 25% of the total number of beneficiaries) may be subject to modest copays.[12]

Table 1

VA Health-Care Priority Groups

| Group | Basis of Eligibility | Share of Enrollees |

| 1 | • Service-connected disability, over 50% disabled, or unemployable

• Medal of Honor recipient |

38% |

| 2 | • Service-connected disability, 30%–40% disabled | 8% |

| 3 | • Service-connected disability, 10%–20% disabled, or tied to discharge

• Former Prisoner of War, or Purple Heart medal recipient |

14% |

| 4 | • Recipient of VA aid and attendance or housebound benefits

• Catastrophically disabled, unrelated to service |

1% |

| 5 | • Annual income below VA means-tested threshold, or eligible for Medicaid

• Recipient of VA pension benefits |

14% |

| 6 | • Service in World War II, Vietnam, Persian Gulf War, or post-9/11 wars

• Exposed to toxic hazards during active duty or training |

5% |

| 7 | • Annual income between the means-tested threshold and the geographical-adjusted threshold | 5% |

| 8 | • Annual income above the means-tested and geographic thresholds

• Continuously enrolled in VA since 2003 |

15% |

Source: VA[13]

Health care is the only U.S. veteran benefit (unlike employment, housing, or education) that delivers services directly through its own institutions. And no other developed nation maintains a similar set of medical facilities dedicated solely to the treatment of its former servicemen. As the number of World War veterans declined, Britain (in 1953), Canada (in 1963), and Australia (in 1998) opened their veteran hospitals to general use.[14]

Most American veterans now possess other forms of health-insurance coverage: 51% are covered by Medicare, 5% by Medicaid, 30% by private insurance, and 28% by TRICARE; only 16% are otherwise uninsured.[15] VA is permitted to bill private insurers (but not other entitlement programs) to treat those with both sources of coverage but may not treat veterans with private insurance who are ineligible for VA-funded care.[16] Veterans enrolled in VA health benefits are ineligible for federal subsidies to purchase insurance from the exchanges established by the Affordable Care Act.[17]

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of VA’s Direct Provision

The direct provision of services by VA hospitals to veterans has helped the VHA integrate treatment and control expenditures, but it has limited veterans’ access to care while often underemploying the system’s resources.

In an influential 2007 book, Phillip Longman argued that VA provided the best care anywhere, and he ostensibly demonstrated the superiority of the collective purchase of medical services by a single public payer.[18] In contrast to fee-for-service payment, which compensates medical providers for delivering low-value services and procedures, Longman argued that VA can allocate health-care resources according to their effectiveness and preventive value. This allows VA to control expenditures without imposing substantial cost-sharing on beneficiaries.

This is particularly important, Longman noted, for an aging population, whose health-care expenditures are associated with the maintenance of chronic medical conditions. VA patients are more likely to receive primary-care checkups, vaccinations, and clinically recommended procedures. He notes that VA’s unique electronic integration of patients’ health-care records facilitates more appropriate care, by allowing clinicians immediate access to information on patients’ medical history, diagnostic tests, medications, and procedures.

Although private insurers have pursued many of the same objectives through managed care, Longman argued that insurers’ incentives to invest in preventive services, which reduce medical costs over the long term, may be undermined by the shift of enrollees between different private insurers over time. Furthermore, he argued, private insurers are wary that they may attract an influx of costly enrollees if they are perceived as particularly attentive to patients with costly chronic conditions.

VA hospitals are also tailored to the special needs of veterans injured in combat. They are staffed disproportionately with former servicemen, who are respectful of veterans’ experiences and sensitive to the traumas and anxieties suffered by those who have been in battle. Facilities have capabilities to assist with spinal-cord injuries, prosthetic limbs, mental-health conditions, and substance-abuse disorders, which are often unavailable elsewhere or unsupported by other payers.[20]

But the efficiency of VA hospital operations has long been hampered by political considerations and the absence of incentives to meet shifting market demand.

The location of VA facilities has largely been determined by protectionism from local members of Congress, who are under pressure from veteran service organizations and a highly unionized workforce.[21] VHA buildings are, on average, 60 years old (seven times the age of the average private hospital), and 20% of facilities are protected heritage sites, which cannot easily be remodeled as needed to house modern medical equipment.[22] As shown in Figure 1, the number of VA hospitals has remained constant for over 50 years, even though the U.S. veteran population has declined steadily and the bulk of procedures once requiring hospitalization are now typically performed on an outpatient basis.[23]

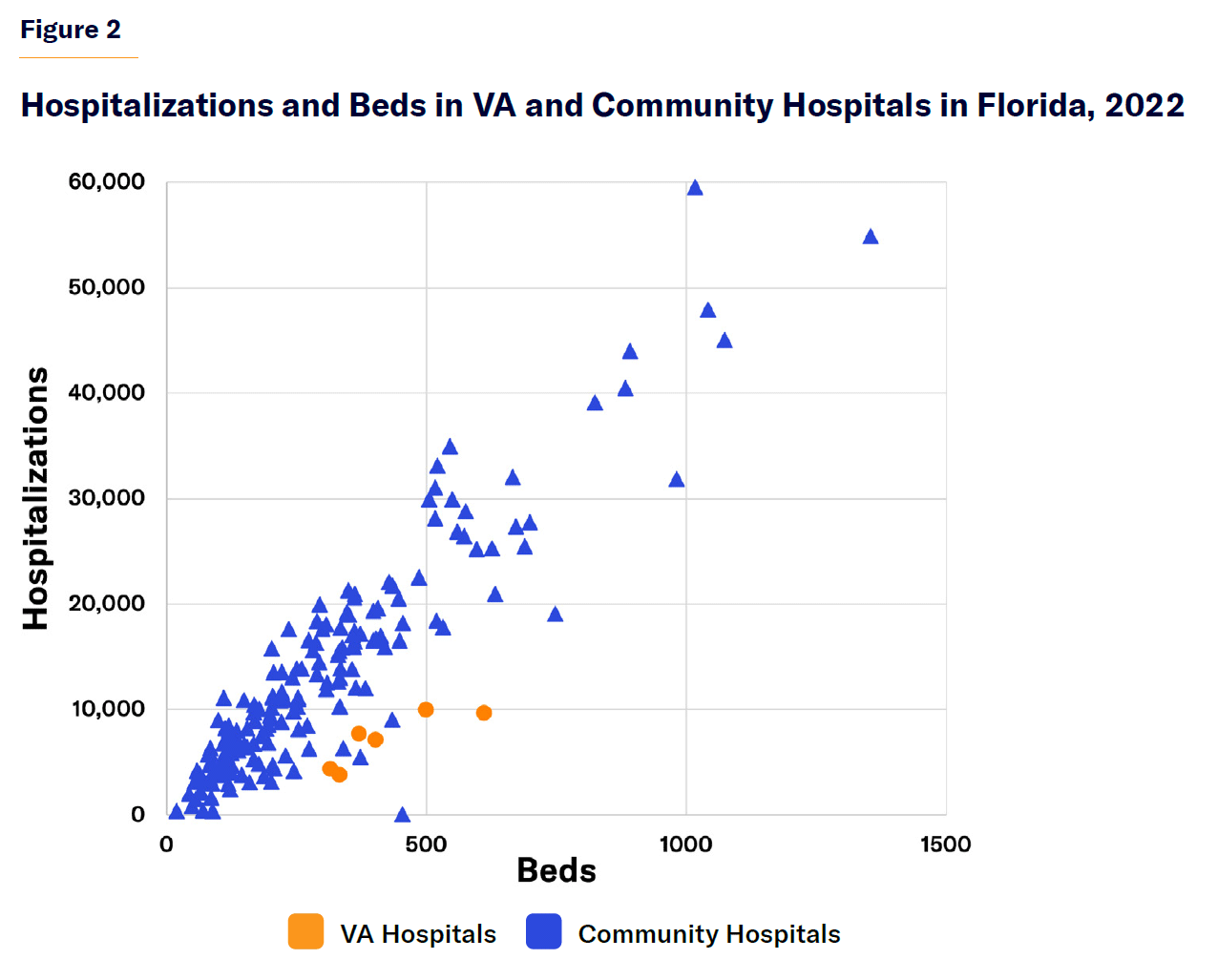

Medical sociologist Paul Starr noted that the VA has long been plagued by simultaneous “duplication on the one hand and underuse of existing capability on the other.”[24] In Florida, VA hospitals treat only a third as many patients as similar-size community hospitals (Figure 2).[25] By the 1990s, the average daily patient census at the VA hospital in Grand Island, Nebraska, was only two.[26] An online reviewer of the facility, which was still open in 2024, notes: “Heroes go to the VA and this place is super clean and sanitized. They are always remodeling and updating spaces and restrooms when they are not acceptable.”[27] This recalls an episode of the 1980s satirical TV comedy, Yes, Minister, which mocked a costly empty public hospital by having its administrator boast of its impressive cleanliness, hygiene, and maintenance.[28]

Today, the VA operates essentially the same hospitals in the same locations as it did in the 1970s, despite a great shift of the veteran population to the Sunbelt. In 1970, far fewer civilian veterans lived in Arizona (0.2 million) than in New York (2.4 million).[29] By 2020, the number in Arizona had surged (to 0.5 million), while that in New York had plummeted (to 0.6 million).[30] While the VA still operates twice as many hospitals in New York as in Arizona, facilities in the Grand Canyon State have been strained.[31] The VA has substantial excess capacity across the country as a whole; but in a few areas, clinicians have been overworked while patients face long waiting times.

Although legislation in 2018 established a process to restructure VA hospital facilities in line with shifts in demand, Congress blocked its implementation in 2022, before it began to take effect.[32]

The VA’s administration is further complicated by requirements prioritizing the recruitment of veterans and union agreements that make it hard to sanction workers for poor performance or misconduct. VA hospitals’ exclusive reliance on public funds often leaves them unable to make major capital investments without extraordinary appropriations from Congress and without the ability to pay competitively with the private sector to attract top staff (particularly specialist physicians).[33]

Because VA health-care funding is distributed through predefined appropriations, resources may fall short of the levels needed to ensure that all possible procedures can be made available with the highest quality.

VA hospitals perform similarly to, or better than, nearby community hospitals on most quality measures and patient satisfaction metrics. But this is largely because they are paid to focus attention and resources on them.[34] Studies finding the VA to have superior performance on target metrics have sometimes not found better medical outcomes.[35] An extensive observational literature comparing medical care received from the VA with community hospitals yields mixed findings on health outcomes, waiting times, and cost.[36]

It is hard to compare the quality and cost of care offered by VA hospitals with privately operated facilities because of differences in patients, the types of services provided, methods of allocating overhead costs, and because most veterans use other sources of care when the VA fails to meet their needs.[37] On average, enrolled veterans receive only 34% of their health care from the VA.[38]

The health outcomes of VA patients cannot simply be compared with those of non-VA patients. VA patients tend to be older and poorer than veterans who do not rely on VA for care.[39] VA facilities are often spartan and inconveniently located, which makes them most attractive to patients unable to afford premiums and out-of-pocket costs associated with private treatment. Access to VA services varies greatly and arbitrarily by region, and its medical centers are often of little use to those who live far from the major cities where they are located.

Some medical needs of veterans are unique. VA patients have similar rates of most chronic medical conditions to similar-aged members of the general population but higher rates of schizophrenia and substance abuse.[40] They also suffer from higher rates of amputations, traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), exposure to toxins, and severe burns, directly resulting from service.[41]

Some patient cohorts may receive better-quality medical care from VA facilities than they would from private ones. After adjusting for patients’ medical risks, a JAMA study found VA patients to have lower rates of mortality and readmissions for major cardiovascular conditions but higher costs across the board. The authors suggested that this may reflect diminished pressure to discharge patients rapidly from the hospital.[42] Other studies have similarly found lower rates of readmissions at VA hospitals following knee replacements or chemotherapy.[43]

A well-designed recent study by David Chan, David Card, and Lowell Taylor attempted to account for the skewed selection of veterans into VA facilities by comparing the fate of emergency patients randomly assigned to ambulance companies with a higher preference for VA hospitals with patients assigned to ambulance companies with a preference for community hospitals. The study found that patients sent to VA hospitals were 46% less likely to die and used 21% less medical care in the subsequent month. The authors argued that this demonstrated that the VA system provided more cost-effective health care, due to the integration and better coordination of medical services and the liability for costs associated with readmissions.[44]

But the implications of this study are likely to be less sweeping than its authors suggest. It only assesses the few areas of the country where VA facilities are a viable option for emergency care, and the VA facilities that it compares are mostly those with adequate or excess capacity. The focus on emergency cases also limits assessments to the aging male patients in need of lifesaving care, who are overtly prioritized by VA facilities’ allocation of resources.

A Congressional Budget Office study concluded that the VA pays less for drugs than other medical systems do. But the VA does not save similarly on physician compensation, as it must recruit doctors from the same labor market, while the absence of fee-for-service compensation leads the VA’s salaried physicians to see 40% fewer patients each. The VA may save on capital expenditures (because it less frequently upgrades its facilities) but often faces higher costs for equivalent construction projects.[45]

The VA delivers fewer low-value diagnostic services and procedures associated with chronic conditions relative to Medicare’s fee-for-service program.[46] But the volume of these services is also similarly reduced by managed care within Medicare, through Medicare Advantage.[47] I.e., the effectiveness of managed care in eliminating needless expenses does not appear to be contingent on the public ownership of hospitals.

However, the cost of specific procedures seems to be consistently higher in the VA than in private hospitals. One study estimated that knee replacements undertaken by VA hospitals cost more than double those at community hospitals, while cataract surgery cost VA three times what it did Medicare.[48] Another study estimated that costs were similar for heart surgery.[49] A 2009 VA assessment concluded that, overall, “VA health care costs 33% more than it would if purchased in the private sector.”[50]

Toward Comprehensive Coverage for Veterans

The VA’s health care system was originally established to treat the wounds of war at dedicated inpatient facilities. But veterans’ eligibility for treatment has gradually been expanded to medical needs that did not arise from combat and to the delivery of care beyond VA hospitals.

Expanded Eligibility

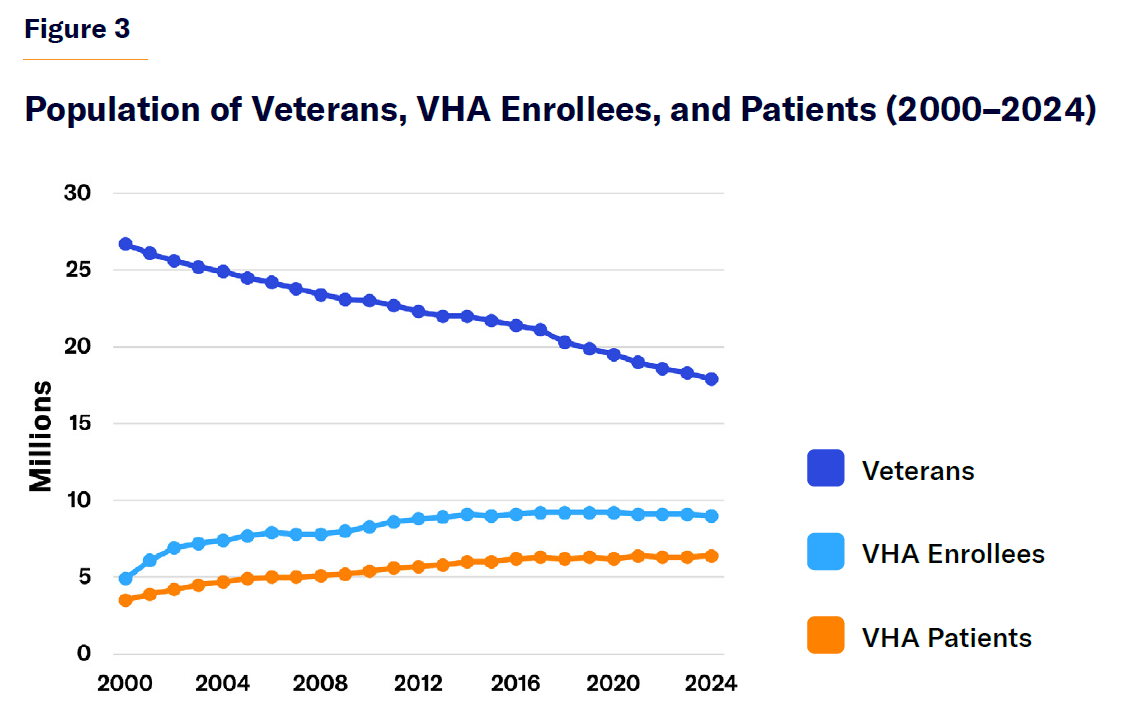

From 2000 to 2024, the total U.S. veteran population declined from 27 million to 18 million because of the deaths of the large veteran population that served in World War II and prior to the 1973 abolition of the military draft. Yet during that period, enrollment in the VA health-care system rose from 5 million to 9 million, and the share of veterans enrolled surged from 18% to 51% (Figure 3).[52]

This increasing proportion of veterans who rely on the VA is due to the expansion of eligibility, much of which resulted from a desire to make use of spare capacity at VA facilities and to avoid overhead costs being concentrated over fewer patients. Economist Sar Levitan noted that, without the extension of eligibility beyond service-connected cases, “the VA contends that the array of ailments would be limited, the turnover of patients reduced, medical expertise would be narrowed, and VA hospitals would be an inadequate base for clinical teaching programs.”[53]

Congress has gradually expanded eligibility for treatment in VA hospitals. In 1924, it first allowed VA hospitals to use their resources to care for non-service-connected ailments.[54] As the use of VA hospitals declined following the 1965 establishment of Medicare and Medicaid (which financed care at community hospitals), VA facilities were allowed to provide free care to all veterans over the age of 65, regardless of income.[55] By 1971, only 20% of patients in VA hospitals were there for the treatment of conditions incurred in service.[56]

Congress has also expanded the types of treatment covered by the VA. In the mid-twentieth century, the VA did not pay for outpatient services for patients whose conditions were not service-connected. But that policy prolonged hospitalizations by preventing the separate treatment of intertwined medical problems, and VA doctors routinely admitted patients to ensure that they would be eligible for treatment. Therefore, in 1973, Congress expanded eligibility for outpatient services to medically indigent veterans when it was deemed “reasonably necessary to obviate the need for hospital admission.”[57] This gradually led to an expansion of outpatient services located away from hospital centers.[58]

The expansion of VA medical benefits owes much to a growing dissatisfaction among veterans and the public with the idea of a neat division between service-connected and non-service-connected conditions. This was particularly true following the Vietnam War, when exposure to the defoliant Agent Orange was recognized to be responsible for aggravating a diverse array of chronic medical conditions, which became increasingly severe in the years after the conflict.[59]

In the 1990s, a major shake-up sought to shift the VA’s focus from the treatment of wounds in inpatient hospitals to the treatment of chronic conditions in outpatient settings.[60] This shift toward integrated care made the patient, rather than a specific service-acquired condition, more the focus of eligibility and funding. As so many veterans are, to some extent, exposed to trauma or toxic substances, limits on the eligibility of veterans for VA health care have become harder for policymakers to maintain as a matter of principle.

Since 2000, the VA has steadily expanded its disability policies to categorize chronic fatigue and several other medical conditions as presumptively service-connected. Presumptive eligibility has been expanded to those with burns and radiation exposure, as well as to all veterans of the Vietnam War, Gulf War, and post-9/11 conflicts—most notably, by the Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxins (PACT) Act of 2022.[61] Furthermore, the diagnosis rates of mental-health conditions are growing rapidly. The VA no longer requires proof of traumatic incidents for eligibility due to PTSD, and the agency recognizes partial hearing loss and lower-back strain as sufficient to justify eligibility. As a result, 45% of Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans have sought benefits due to service-connected disabilities—more than twice the rate of Gulf War veterans.[62]

As politicians now typically discuss VA health care without the notion that it ought to be limited to treating medical conditions resulting from military service, the program seems to be on a course for the universal eligibility of veterans—inhibited only by fiscal constraints. Despite the declining veteran population, there has therefore been a rising demand for VA services, yielding shortfalls in many areas, particularly the parts of the country where the veteran population has actually grown.

In 2014, a whistleblower claimed that as many as 40 veterans had died waiting for treatment at the VA’s medical center in Phoenix.[63] Evidence had emerged that staff in another VA facility had manipulated statistics by holding patients on secret waiting lists.[64] An official audit of the Phoenix system, which did not corroborate the whistleblower’s most striking claims, identified widespread evidence that employees had obscured patients’ waiting times in official records.[65]

That crisis could have been an opportunity to adjust the distribution of resources to where they are most needed. But instead of shifting VA resources to match the geographic distribution of patient needs, Congress in 2014 passed the Veterans Choice Act. This provided $10 billion in additional funding over three years for private medical providers to treat veterans who had to wait over 30 days or who had to drive over 40 miles to receive treatment from the VA.[66] The legislation also commissioned a RAND study to investigate the shortfalls in timely access to quality care for veterans. RAND found that while waiting times for VHA care were typically similar to those in the private sector, long waits at some facilities placed patients at risk of poor health outcomes. It further noted that veterans who live far from VHA facilities would struggle to receive needed specialty services.[67]

In 2018, following the expiration of the Choice Act, Congress enacted the VA MISSION ACT, further expanding payment for veterans to receive care from community providers. Veterans would be eligible for private care if patients needed to travel more than 30 minutes for primary care or 60 minutes for specialty care; if they had to wait more than 20 days for primary care or 28 days for specialty care; or if VA physicians determined that it was otherwise in the best interests of patients to receive private care.[68]

After the 2014 VA Choice Act, average waiting times at VA facilities (17.7 days) were shorter than those in the private sector (29.8 days).[69] Veterans who lived beyond the 40-mile cutoff in eligibility for VA-funded private surgery became more likely to receive surgery from private institutions and to have it paid for by the VA, but did not see significantly different postsurgical outcomes.[70] The 2018 MISSION Act coincided with a shift in payment for non-VA emergency visits from Medicare to the VA, without any overall change by veterans in the utilization of VA facilities.[71]

By 2022, 40% of enrolled veterans had received some “community care” (VA-financed care from non-VA providers).[72] This appears to have unleashed pent-up demand for the VA to pay for medical care. From 2012 to 2022, the volume of care provided directly by the VA increased from 740 million to 851 million Global Relative Value Units (GRVUs), the metric used to determine the cost value of health-care services, while the volume provided at other hospitals and facilities increased from 130 million to 530 million.[73]

Although community care still depends upon fixed appropriations, it has created pressure on Congress to expand expenditures. The Congressional Budget Office noted that the VA “has limited ability in the near term to control the use of community care once a veteran has been approved to seek it.”[74]

VA spending on privately delivered care surged from $4 billion in 2010 to $31 billion in 2024.[75] Spending on community care owed much to emergency care, home health assistance, and rising volumes of diagnostic tests.[76] The VA’s inspector general has suggested that the lack of internal controls puts the VA “at risk of improperly paying” for community care, with 38% of participating medical providers overcharging the government for care.[77]

The growth of spending on community care and the declining veteran population have not led to reductions in costs associated with the direct provision of care. Rather, during 2013–23, the VA’s number of direct full-time employees surged from 257,665 to 373,997.[78]

During 2019–23, the number of inpatient admissions at VHA facilities declined by 19%, while the number of outpatient encounters fell by 5%. Over that period, spending nonetheless increased by $42 billion. Of that increase, 15% was due to community care, 9% was due to an increased number of users, and 74% was due to increased costs of labor and supply costs associated with the direct provision of hospital care.[79]

This has left VHA facilities conspicuously inefficient. In 2023, 55% of VA inpatient-care GRVUs were delivered by community hospitals, but community care accounted for only 38% of VA expenditures on inpatient care.[80]

The Cost Challenge

The combination of expanded eligibility for benefits and expanded payment for privately delivered care, without offsetting reductions in funding for VA facilities, has driven up the program’s overall expenditures.

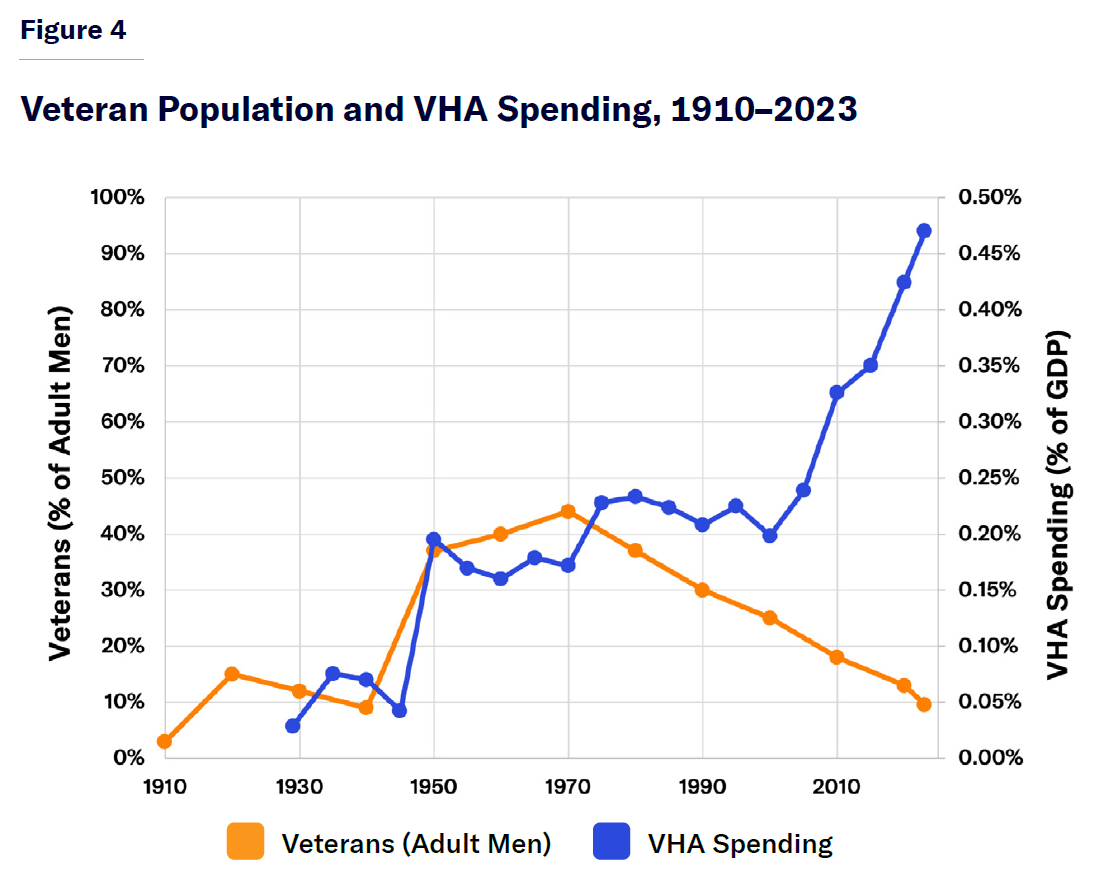

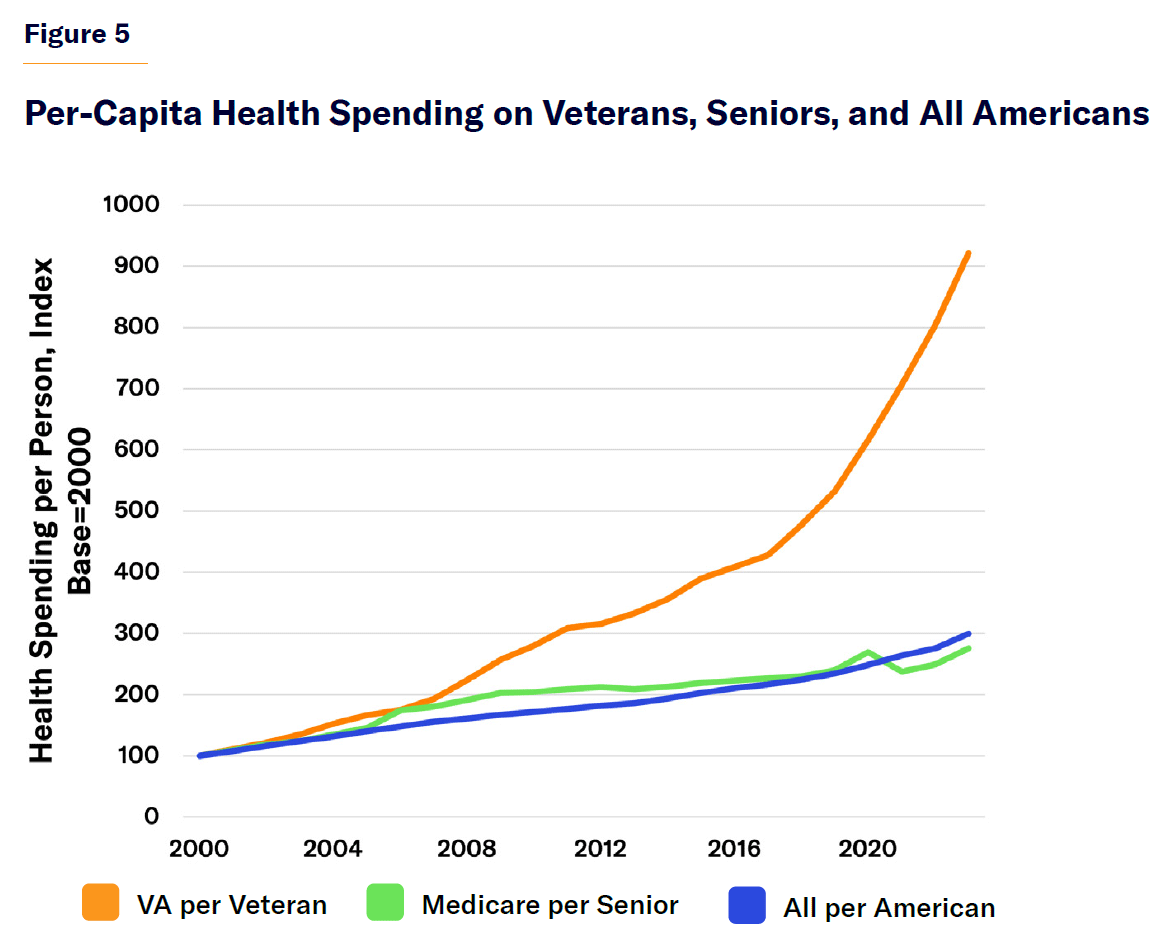

During 2014–23, federal spending on veteran health benefits surged from $59 billion to $127 billion, even though the U.S. veteran population declined from 22.0 million to 18.3 million (Figure 4).[81] Although the increase in veteran health spending owes something to rising medical capabilities and the aging of the population, its per-capita spending has greatly outpaced Medicare (Figure 5).

The quality of VA health care has improved recently, largely because of increased funding per patient. The program’s cost per enrollee ($13,938 in 2023) has risen to almost the same level as Medicare ($15,547), even though the VA pays for only 34% of enrolled veterans’ health care (the rest is covered by other sources, such as Medicare, Medicaid, TRICARE, or paid for out-of-pocket).[84]

Expand Access to VA Care

Politicians of both parties appear eager to further expand veterans’ eligibility for VA health care as well as access to privately delivered medical services. Yet a congressional commission estimated that the provision of comprehensive federally financed benefits to all veterans could more than triple the total fiscal cost of the program.[85]

The VA’s health-care benefits were originally established prior to Medicare, Medicaid, or even the existence of widespread private insurance. Today’s world is quite different. As 84% of veterans already have health-insurance coverage from another source, much of the expenditure caused by expanding the eligibility and scope of VA health-care benefits serves to displace other sources of financing for health care.[86]

In the cases of Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care, the expansion of VA payment for care often merely duplicates public payments for insurers to cover the same services that have already been made. The Wall Street Journal in 2024 estimated that the federal government paid Medicare Advantage plans an average of $11 billion per year to cover beneficiaries who were also users of VA services.[87] A Harvard study estimated that Medicare Advantage plans were paid $1.3 billion in 2020 to cover VA enrollees who did not use any Medicare services at all.[88]

It is clearly possible to reduce wasteful spending associated with the federal government paying twice for the same patient to be treated. But allowing Americans ineligible for VA-funded care to receive treatment from VA hospitals would also save taxpayers money, by expanding the number of patients over whom overhead costs of VA facilities could be spread. Indeed, 84% of hospital expenditures are fixed costs, which do not vary directly with the number of patients treated.[89]

In 1975, economist Cotton Lindsay argued that “it makes little sense today to restrict arbitrarily a potential resource for general use (a hospital) to the use of a narrowly defined group (veterans).”[90] Fifty years later, the point is even stronger.

The veteran population is now much diminished and more dispersed across the country, and the bulk of treatment delivered by VA facilities is for the same medical conditions afflicting all aging Americans. That is what has made the delivery of VA services through community care feasible—and so appealing.

Some have argued that the growth of VA payment for community care threatens VA’s integration of medical care by fragmenting the delivery of care.[91] But the delivery of care to VA patients has long been highly fragmented because VA enrollees receive 70% of their medical care from other providers.[92] As Paul Starr noted, because “private doctors are not allowed to treat patients at VA hospitals and VA doctors are not supposed to have private practices,” the VA system is “sharply separated” from the rest of the health system.[93] A growing partnership between VA facilities and private insurance could therefore improve the integration of veterans’ medical care.

Proposal

VA hospitals should be permitted to treat and bill Americans covered by other insurance plans (privately financed, Medicare Advantage, or Medicaid managed care), regardless of their eligibility for VA-financed care.[94]

As the veteran population continues to decline, the problems of overcapacity and hospital costs being increasingly concentrated on a smaller number of patients are likely to worsen. A case could be made for reducing the institutional footprint of VA facilities. But Congress has repeatedly demonstrated that it is unwilling to cut funding for existing VA hospitals, as this may threaten their continued operations.[95] Policymakers should therefore attempt to make better use of these facilities, so that their fixed costs can be spread over more patients.

Allowing VA hospitals to treat non-VA-funded patients would increase the availability of affordable treatment to privately insured patients. An increase in patient volumes at VA hospitals would also help spread fixed costs over more patients, making facilities more cost-effective for all payers. While new private revenues would pick up a portion of existing overhead costs, public funds should continue to be reserved entirely for the provision of care to eligible veterans. Treatment at VA hospitals should continue to put veterans first, according to current priority group classifications.

This proposal would provide increased revenues to allow the continued maintenance of VA institutions, without increasing federal expenditures per patient as the veteran population continues to decline. It would also end the double payment for veterans receiving care through the VA who are also enrolled in Medicare Advantage or Medicaid managed care.

Formalizing payment arrangements for not-currently-eligible Americans to receive care at VA facilities would reduce the political pressure for ever-broader expansions of VA appropriations to cover already-insured veterans. It would also establish a principled boundary on publicly financed VA funding—limiting the crowd-out of private insurance because of increased public-sector spending.

Furthermore, the growth of private financing of VA care would increase the responsiveness of VA facilities to market demand and their accountability to competition. Combined with the continued growth of VA-financed community care, this would encourage a gradual shift of VA resources to where there is less duplication of services that can be delivered or financed privately.

Conclusion

The VA health-care system was originally established to treat the wounds of war at a dedicated set of federally operated hospitals. Yet over time, the veteran population has declined, while care has increasingly shifted to outpatient settings. To avoid the costs of VA hospitals being concentrated on fewer patients, Congress has repeatedly expanded eligibility for VA care beyond the treatment of service-connected conditions.

But VA facilities established a century ago are poorly aligned with today’s veteran population or the delivery of modern medical services. Although a few facilities may be overstrained, the veteran population has declined in most parts of the country. When Congress has provided additional funding for veterans to receive treatment from private providers, it has not obtained any offsetting reduction in costs at existing facilities.

Members of Congress are highly protective of federally funded hospitals in their home districts and have resisted attempts to rationalize the VA hospital system for decades. But if Americans who are currently ineligible for VA-funded care were permitted to obtain treatment from VA hospitals, they could obtain improved access to care, while also providing private revenues to support VA hospitals without the need for ever-escalating federal funds.

Endnotes

Photo: Johnrob / E+ via Getty Images

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).