Executive Summary

This report presents analyses of the state of education in New York City ahead of the approaching mayoral primaries and election. It focuses on the role that the mayor can and should play in bringing the city’s school system to much greater levels of success than it is currently achieving. The underlying theme of this report is that the current depressed state of achievement in the school system is the result of poor decisions made during the de Blasio administration and the slow and timid attempts at reform from the Adams administration. We reject the notion that our schools have declined solely because of the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic or that the current direction of the federal government will make improvements in our schools. This report points to the successful policies of the Bloomberg administration as evidence that real improvement is possible with an unrelenting focus on school accountability, the expansion of educational opportunity through a dynamic system of new school creation, and the closure or merger of underperforming and under-enrolled schools.

After a brief introduction, the report will discuss nine critical areas for the city’s schools. It will end with 18 specific recommendations to strengthen the Department of Education’s programs and schools, expand educational choice and innovation, and mount a necessary legislative effort in Albany to facilitate true reform and develop a family and community focus to make New York City and its schools attractive to families once again.

Introduction

For the last 12 years, New York City’s schools have been on the wrong path, thanks to legislative and executive actions in city hall and in the state capital. Whoever is mayor in January 2026 must appoint strong leaders at the Department of Education (DOE) with a clear mandate: ensure that new spending mandated by the state legislature and city council is paired with guardrails of accountability and family choice. Without those guardrails, additional funding will be squandered with little impact on student performance. For guidance, the mayor’s education team can learn from the successes of the city’s own charter-school sector as well as initiatives outside the city, which combine proven pedagogic practices in reading and math with content-rich curricula, not limited to skills alone.

NYC can also learn from its own history of successful school reform, particularly the period of 2002–14, when student performance improved measurably and many communities gained access to educational opportunities that had been absent for decades. The 2002–14 reform effort emphasized accountability for school performance, support for innovation in both the district school and charter sectors, and expanded choice of schools for all communities in NYC.

Unfortunately, the success of that reform was deliberately undone during Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration. Beginning in 2014, de Blasio weakened school accountability and blocked the creation of new innovative schools, thereby limiting any expansion of school choice for the city’s families. City hall also chose redistribution rather than growth in allocating available seats in the city’s academically selective middle schools and high schools. In the last four years, the Adams administration also inexplicably devolved control to unelected community superintendents, while simultaneously attempting to impose centrally planned curriculum and programs.

Throughout both the reform and its undoing, the school system has received growing funding and staffing, even as enrollment and the city’s birthrate plummeted. In current and recent years, the city council and the state legislature have argued that school and district budgets should not be reduced in the face of enrollment declines, resulting in tremendous inefficiencies as performance stagnates or even declines.

The Covid pandemic dealt a blow to all schools in the city, but private, religious, and charter schools have since bounced back. DOE schools have not. Their continued low performance is the result of decisions made in city hall and at DOE headquarters in the Tweed Courthouse. In contrast, many districts and states across the country have rebounded from the pandemic by adopting curricular and pedagogical reforms alongside greater educational pluralism and school choice. Many states have also adopted universal school-choice programs, which have led to growing enrollment. To remedy their long-term enrollment decline, New York City and State must offer families more and better school options.

This report first identifies the most pressing issues facing NYC schools and explains how policy decisions have caused each of these issues. Finally, the report offers specific recommendations for the next mayor to implement to reform the city’s schools.

Low Student Performance

Some 15 years ago, NYC was considered a national model for urban school improvement. But student achievement levels in the city’s schools have since declined sharply.

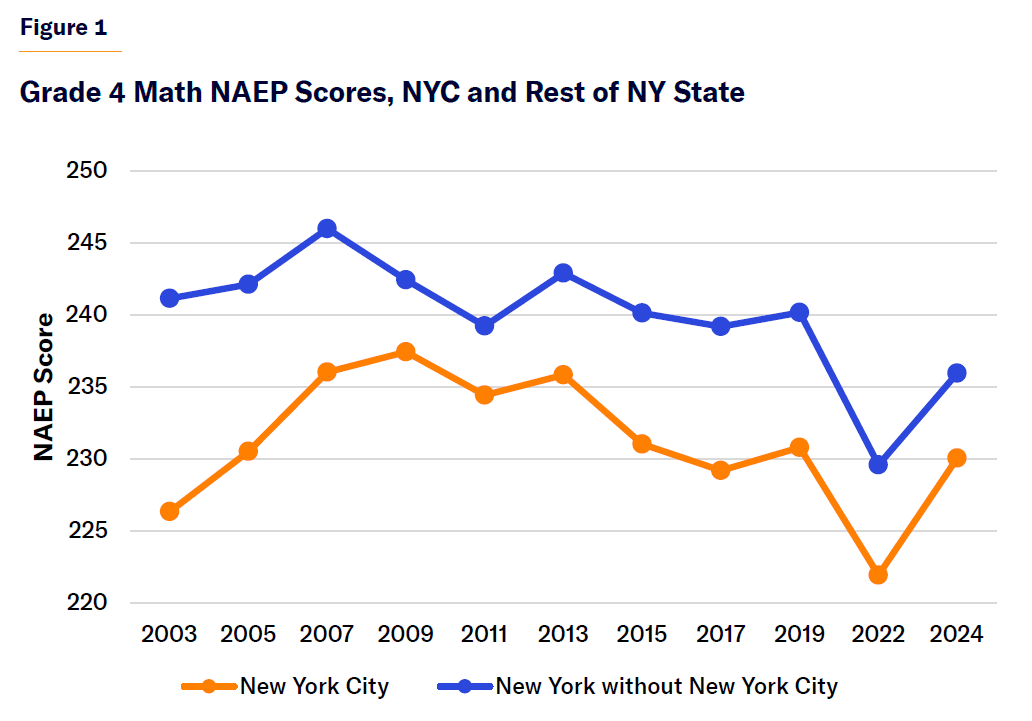

As shown in Figure 1, the city’s fourth-grade math scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) peaked in 2009, then slid a few points before dropping severely due to the Covid shutdown–related learning losses. Scores did rise in 2024, but the increase was driven by improvement among the highest-scoring students, with no improvement among the lowest-scoring. (This was true for the nation as a whole, though New York State saw improvement for both the low- and high-achieving groups.)

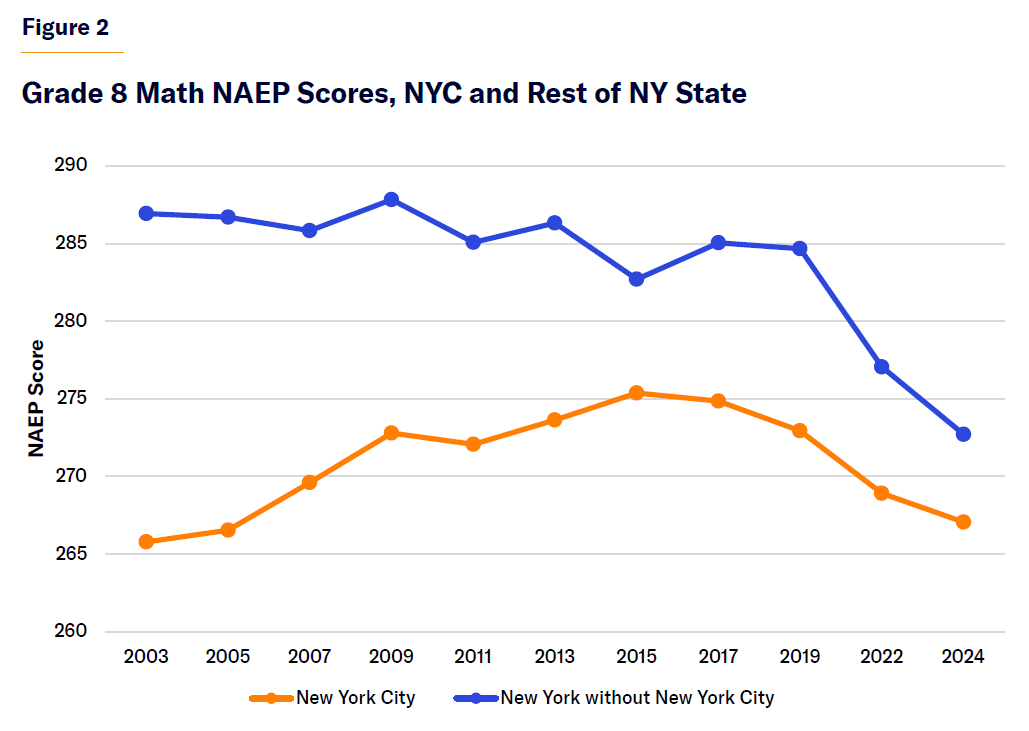

The city’s eighth-grade math scores peaked in 2015 and have declined since, with scores in 2024 nearly identical to those in 2003 (Figure 2).

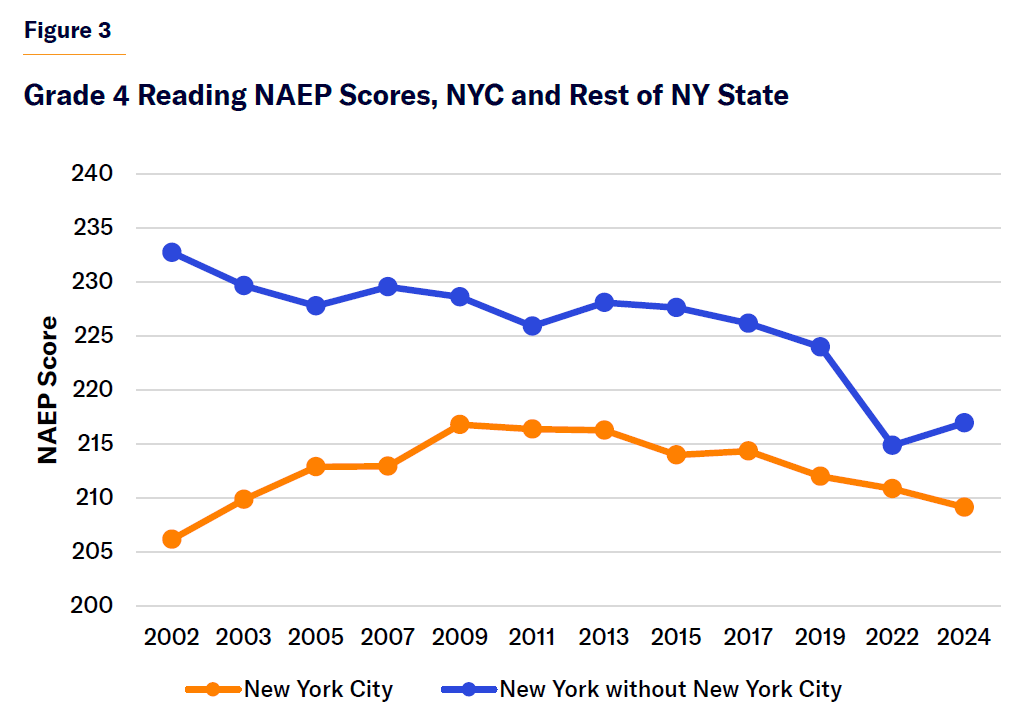

The city’s fourth-grade reading scores peaked in 2009, remained stable until the Covid shutdown, and have changed little since (Figure 3). Fourth-graders in 2024 did not fully participate in the Adams administration’s NYC Reads initiative, which was first introduced in the 2023–24 school year.

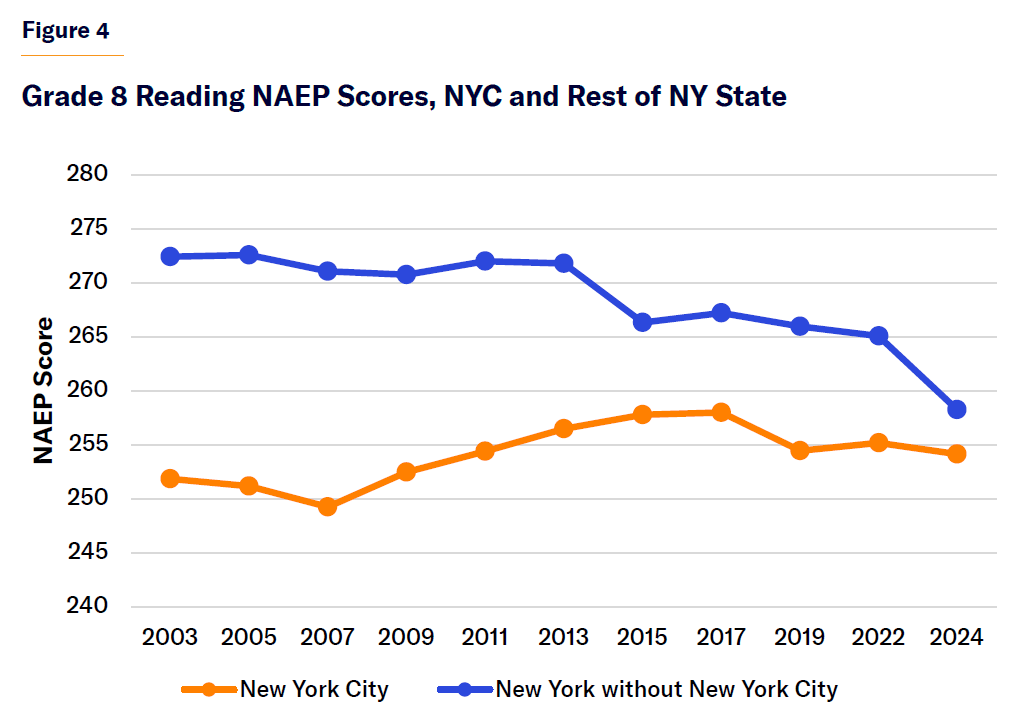

The city’s eighth-grade reading scores improved from 2003 through 2017 but have since been largely stagnant (Figure 4).

Beginning in 2018, the city turned away from the approaches that had measurably improved the performance of its schools and increased educational opportunity for students in the city’s historically underserved communities.

The mayor and the legislative leaders in the city council and state legislature stopped the expansion of school choice—a process in which low-performing schools were closed and replaced by new and better charter and district schools—which reduced schools’ accountability for student performance. Instead, education leaders returned to a strategy that never works: throwing more money into the system without fundamental changes that would make the money useful for improving student outcomes.

The city’s schools are not improving because the current political priorities in city hall and the legislature are not working, much as they did not work the last time they were tried, prior to the onset of mayoral control in 2002.

All-Time Low Attendance

Absenteeism has been on the rise nationwide since schools reopened after the Covid-19 pandemic. The Return to Learn Tracker, produced by the College Crisis Initiative (C2i) and the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), shows that the average chronic absenteeism rate almost doubled between 2019 (15%) and 2022 (28%).[1] Virtually every school district has experienced increased student absenteeism, but the increase has been concentrated in districts with low academic performance and high numbers of low-income students.

NYC’s rate of absenteeism is above the national average. The New York State Education Department defines chronic absenteeism as missing 10% or more of the total days throughout the school year.[2] NYC public schools entered the pandemic with a 26.5% chronic absentee rate, which increased to 34.8% at the end of the 2023–24 school year.

For the past few years, New York families have been told by elected officials that they should keep their kids at home at the faintest hint of any illness in order to keep them and others safe. Families have internalized that advice. Unless they hear a different message, this behavior will continue.

Elected leaders should lead a campaign to explain to families the importance of regular attendance in school and its impact on kids’ success, not only in school but in life. It is particularly important that this message is aimed at the early grades, which have seen the highest increases in absenteeism. In addition to messaging, there should not be any new measures that allow for more excused absences, such as mental-health days.

Fixing chronic absenteeism requires understanding which students are chronically absent and why. We need more data, not less. The leading states on this issue have published, with regular updates, attendance and chronic absenteeism rates. Unfortunately, as shown in Table 1, New York is heading in the opposite direction. It only published 2023–24 absenteeism rates in February 2025. Even more alarming is the proposal of the NYS Education Department to remove these metrics as measures of success in schools.

Table 1

Increase in Portion of Chronically Absent Students by Subgroup

| Grade | Subgroup | Chronically Absent SY 2018–19 | Chronically Absent SY 2023–24 | Increase in % of Chronically Absent |

| All Grades | All Students | 26.5% | 34.8% | 8.3 |

| All Grades | Students with Disabilities | 37.1% | 44.8% | 7.7 |

| All Grades | Students in Temporary Housing | 42.6% | 51.7% | 9.1 |

| All Grades | Low-Income | 30.4% | 39.1% | 8.7 |

| All Grades | English Language Learners | 28.0% | 39.7% | 11.7 |

| All Grades | Asian | 13.3% | 19.6% | 6.3 |

| All Grades | Black | 34.3% | 41.5% | 7.2 |

| All Grades | Hispanic | 31.8% | 41.7% | 9.9 |

| All Grades | Other | 23.2% | 30% | 6.8 |

| All Grades | White | 17.2% | 26.2% | 9.0 |

Shrinking Enrollment and Changing Demographics

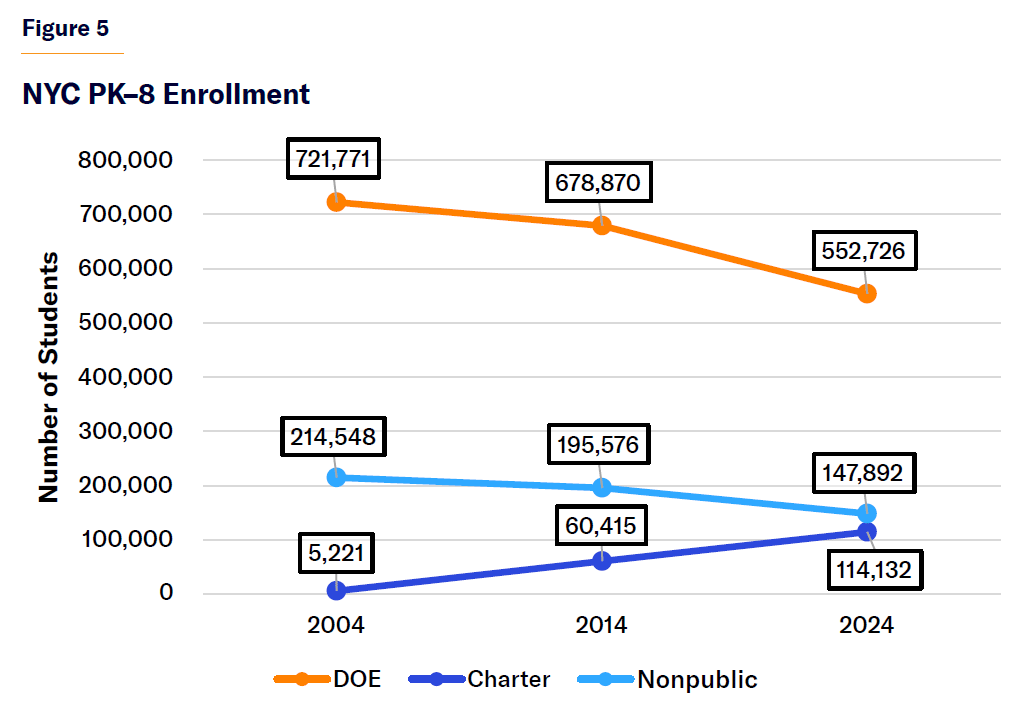

Enrollment in pre-K through eighth grade is a leading indicator of where overall enrollment is headed. In DOE schools, that figure is down by almost a quarter in the last 20 years, with most of the decline (19%) occurring in the last 10 years (Figure 5). Kindergarten enrollment has decreased by 17% since the 2016–17 school year. The influx of migrant students in the past two years stemmed the decline, but border crossings have plummeted since January, and the city cannot expect an ongoing influx of migrants. Charter schools have grown tremendously since their inception in 2019, but their continued growth has been capped by the state legislature. Enrollment in private and religious schools has dropped by 31% since 2004, driven by huge retrenchment in the city’s Catholic schools, offset somewhat by growth in Jewish schools serving Haredi communities.

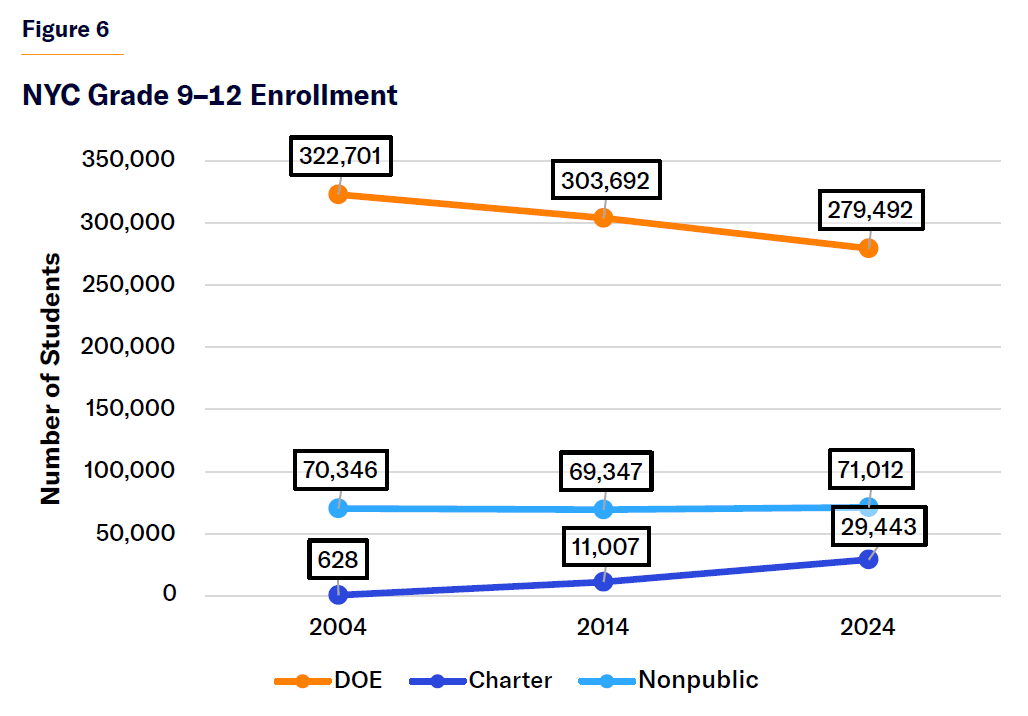

Enrollment declines have been smaller in the city’s high schools, at only 13% (Figure 6). But this is a lagging indicator: the smaller cohorts now in the lower grades will continue to push high school enrollment down in the coming years. Enrollment in private and religious high schools has remained about the same since 2004, with loss in Catholic schools being offset by growth in Jewish schools. Charter high schools have grown but account for less than 8% of the city’s high school students.

Some 20% of the city’s schoolchildren are enrolled in private and religious schools, and another 12% are in charter schools. Although only about 1% of students in the city are homeschooled, their numbers have roughly doubled since 2019. Although these students are not attending DOE schools, the mayor still represents them and their families and has a duty to protect their access to education.

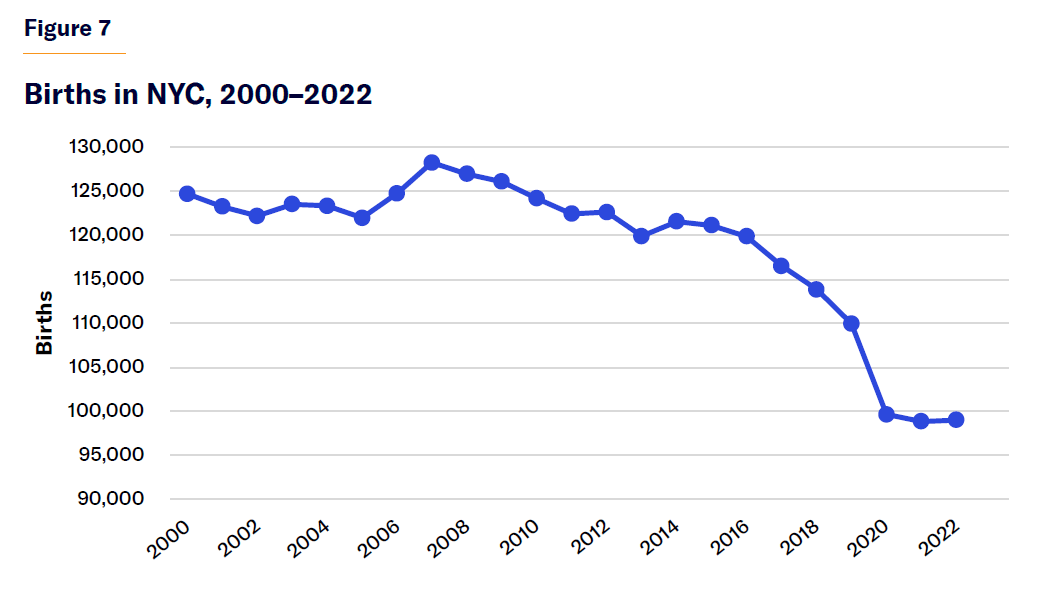

Some of the decline in enrollment in the city’s schools is due to net out-migration from New York City. But the biggest driver is fertility: since 2000, the number of children being born in the city is down by more than 20% (Figure 7).

Enrollment in DOE schools is considerably down and not likely to rebound in the foreseeable future.

New York City has become less hospitable to families with children. This is true for many reasons beyond poor school performance. The cost of housing and the shortage of affordable housing are clearly part of the puzzle. As will be made clear below, much of the decline in births has happened in neighborhoods in Brooklyn and Manhattan that were previously mostly Hispanic and black but that, over the last 20 years, have been attracting younger white residents. Many of these new residents are childless or are sending their children to charter or nonpublic schools or to public schools outside their district of residence.

This type of ethnic change is nothing new for NYC history, but the current situation requires that city leaders find a way to convince families that the city is a safe and nurturing place to raise children. More and better schools are part of the solution, but so are noneducational concerns. Families want safe and orderly streets and want to be able to afford children and housing in the city. As enrollment continues to decline, the city needs to consider whether some of the money being spent on schools would better serve families and children in other ways.

As shown in Table 2, the racial and ethnic mix in DOE schools is changing, as it has been for 20 years. The change is most acute in the early grades but will become apparent in high schools in the coming years. No group is monolithic in its educational preferences, but demographic changes are likely to change the politics of education in the city.

Table 2

| Enrollment in Grades K–8 by Racial/Ethnic Group | Change | ||||

| Group | 2004 | 2014 | 2024 | 10 years | 20 years |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 3,305 | 5,812 | 7,704 | 33% | 133% |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 89,861 | 115,217 | 116,513 | 1% | 30% |

| Black | 231,247 | 169,715 | 105,870 | –38% | –54% |

| Hispanic | 282,980 | 288,319 | 251,492 | –13% | –11% |

| Multiracial | n/a | 5,159 | 13,776 | 167% | n/a |

| White | 103,866 | 114,555 | 107,260 | –6% | 3% |

| Total | 711,259 | 698,777 | 602,615 | –14% | –15% |

In the second half of the twentieth century, the city and nation were, of necessity, focused on educational civil rights as they attempted, often unsuccessfully, to rid public schools of racial segregation. In the 1980s and 1990s, the focus was on expanding educational opportunity and school quality in all communities, regardless of the racial makeup of schools. The creation of new and better public schools in lower-income minority neighborhoods was particularly strong in New York City, as educators in several local districts created new “alternative” schools, with measurable success. This eventually led to the establishment of charter schools, with public funding but independent from a centralized school system.

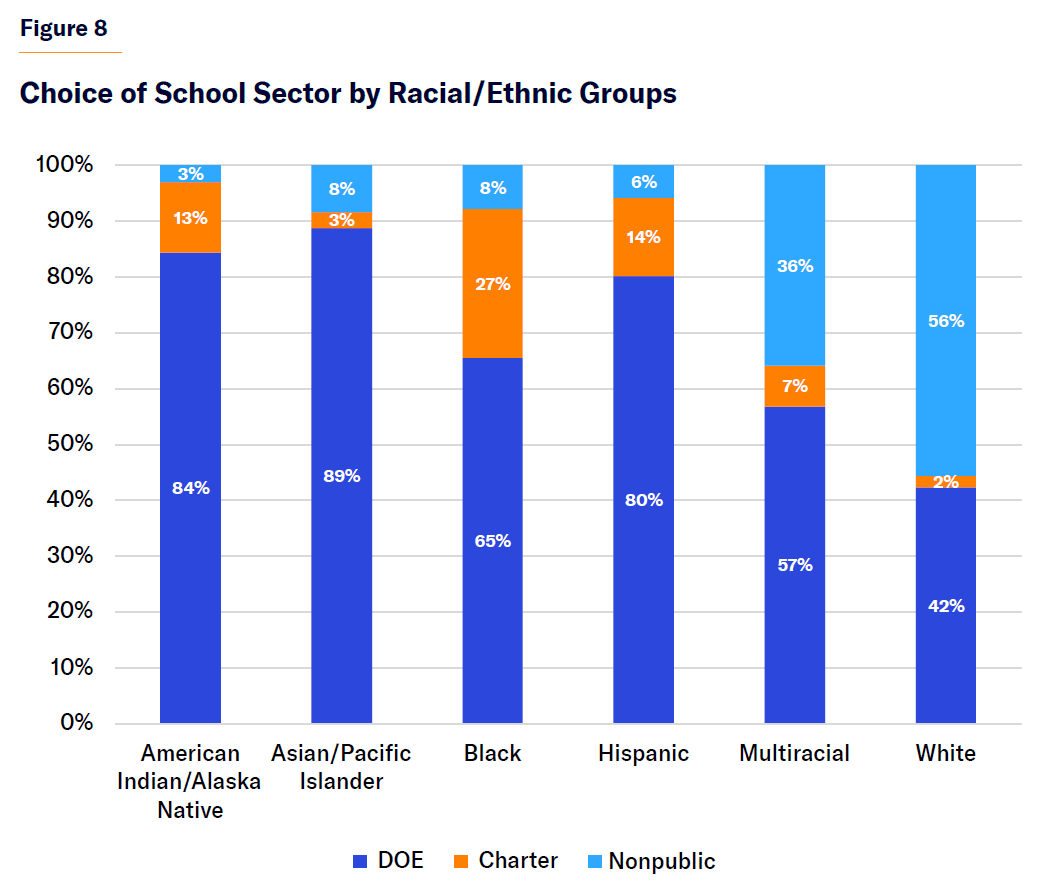

Unfortunately, during the de Blasio mayoralty, the city decided to redistribute seats in selective public schools, rather than increase the number of seats. The large number of Asian students in these schools became the punching bag in this effort, engendering a strong and effective pushback. Today, Asian American students are the second-largest group in the city’s elementary and middle schools; whites are the third-largest group. Black enrollment is less than half what it was in 2000, partly because the most successful civil rights initiative in the city’s educational history was the establishment of charter schools, which now educate 27% of the city’s black students (with another 8% in private and religious schools) (Figure 8).

Today, 89% of the city’s 176,000 Asian students in grades pre-K–12 are enrolled in DOE schools. The strongly held cultural preferences for advanced curriculum and merit admissions in many of these students from East and South Asia, in particular, will almost certainly increase demand for more, not fewer, seats in academically advanced and selective middle and high schools.

Imbalances in School-District Size Lead to Inefficiency

Because the enrollment decline has not occurred uniformly throughout the city but has been concentrated in particular neighborhoods, another consequence is that school districts have become very different in size, which poses large challenges for cost-efficiency and organizational capacity.

Table 3

| NYC Districts Sorted by PK–8 Enrollment in 2004–24 | Change | |||||

| Borough | District | 2004 | 2014 | 2024 | 10 years | 20 years |

| Brooklyn | 16 | 9,970 | 6,157 | 3,940 | –36% | –60% |

| Manhattan | 5 | 11,743 | 8,229 | 5,043 | –39% | –57% |

| Brooklyn | 23 | 11,941 | 8,404 | 5,787 | –31% | –52% |

| Manhattan | 1 | 8,270 | 8,462 | 6,801 | –20% | –18% |

| Brooklyn | 32 | 15,604 | 11,164 | 6,806 | –39% | –56% |

| Brooklyn | 18 | 17,905 | 12,700 | 7,438 | –41% | –58% |

| Manhattan | 4 | 13,066 | 10,003 | 7,761 | –22% | –41% |

| Bronx | 7 | 15,007 | 12,483 | 8,102 | –35% | –46% |

| Brooklyn | 13 | 12,765 | 10,216 | 8,218 | –20% | –36% |

| Brooklyn | 14 | 14,964 | 12,687 | 9,274 | –27% | –38% |

| Brooklyn | 17 | 23,533 | 16,017 | 10,148 | –37% | –57% |

| Manhattan | 3 | 14,700 | 13,278 | 11,393 | –14% | –22% |

| Bronx | 12 | 18,404 | 17,405 | 11,408 | –34% | –38% |

| Manhattan | 6 | 26,643 | 18,238 | 12,131 | –33% | –54% |

| Brooklyn | 19 | 22,559 | 17,684 | 12,595 | –29% | –44% |

| Bronx | 8 | 22,666 | 20,458 | 15,977 | –22% | –30% |

| Queens | 26 | 16,612 | 16,759 | 16,099 | –4% | –3% |

| Queens | 29 | 25,262 | 22,415 | 17,413 | –22% | –31% |

| Bronx | 9 | 31,310 | 26,782 | 17,457 | –35% | –44% |

| Brooklyn | 22 | 27,884 | 24,164 | 19,933 | –18% | –29% |

| Brooklyn | 15 | 20,842 | 23,388 | 20,116 | –14% | –3% |

| Brooklyn | 21 | 22,943 | 21,378 | 22,011 | 3% | –4% |

| Manhattan | 2 | 21,776 | 25,145 | 22,535 | –10% | 3% |

| Queens | 28 | 23,120 | 23,894 | 22,650 | –5% | –2% |

| Bronx | 11 | 29,341 | 28,727 | 22,778 | –21% | –22% |

| Queens | 25 | 22,114 | 25,040 | 24,543 | –2% | 11% |

| Queens | 30 | 29,365 | 29,058 | 25,767 | –11% | –12% |

| Bronx | 10 | 41,124 | 37,848 | 27,034 | –29% | –34% |

| Queens | 27 | 32,857 | 33,285 | 28,341 | –15% | –14% |

| Brooklyn | 20 | 28,814 | 34,574 | 32,059 | –7% | 11% |

| Queens | 24 | 36,874 | 42,329 | 35,611 | –16% | –3% |

| Staten Island | 31 | 41,281 | 40,988 | 38,908 | –5% | –6% |

Table 3 examines enrollment in prekindergarten through eighth grade because those grades are led by a local Community Education Council and superintendent in each district. High schools have their own Community Education Council and superintendent.

The 22 smallest districts in the city, based on 2024 enrollment, account for 85% of the enrollment loss in these grades since 2004 (Figure 9). Cumulatively, they enroll fewer students than the 10 largest districts combined.

While district offices are not large, DOE does budget over $300 million per year and employs 2,400 staff in school support organizations, which include the 32 districts as well as organizations for the high schools and three other citywide organizations.

Beyond cost concerns, the mayor should consider whether district consolidation might improve the quality of leadership for all schools. That said, the existence of the 32 districts and the requirement that each have a superintendent and support staff is a matter of state education law. Any change would require legislative approval.

Though the city has begun to consolidate small schools, it has been done slowly. Just this year, the city announced the closure of an elementary school in Brooklyn with fewer than 60 students enrolled. The city had attempted to close the school once before but was blocked from doing so by the courts. But as shown in Tables 4 and 5, several schools across the city still have very few students.

Table 4

| Schools with | ||

| Borough | 150 or Fewer Students in Grades PK–8 |

151–200 Students |

| Manhattan | 3 | 10 |

| Bronx | 4 | 5 |

| Brooklyn | 11 | 25 |

| Queens | 3 | 1 |

| Staten Island | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 22 | 43 |

Table 5

| Schools with | ||

| District | 150 or Fewer Students in Grades PK–8 |

151–200 Students |

| 5 | 3 | 4 |

| 13 | 3 | 5 |

| 14 | 1 | 3 |

| 16 | 1 | 4 |

| 17 | 1 | 5 |

| 19 | 1 | 3 |

| 23 | 2 | 2 |

Low enrollment does not necessarily mean that a school is low quality, but the consolidation of small schools can lead to both cost savings and educational improvement if done strategically—by replacing weak school leadership with stronger teams.

DOE’s Bloated Budget

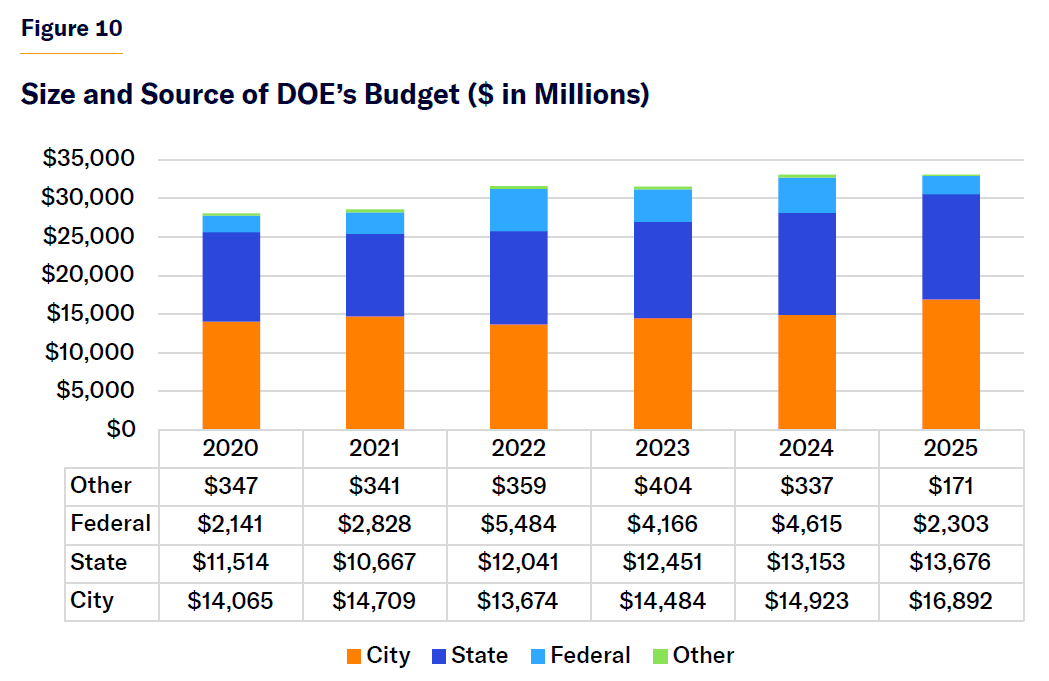

Even though DOE is now educating fewer students, its budget has grown steadily in the last five years. Enrollment is down by 128,000 students, or 13%, between 2020 and 2025. At the same time, DOE’s budget grew by 17.7%. City funding grew by 20%, state funding by 19%, and federal funding by 8% (Figure 10).

Charter-school funding is determined by the NYS Education Department, according to a legislatively determined formula. The funding passes through DOE’s budget to individual charter schools from state and city sources. Federal funding for charters flows directly from the state to individual charter schools. In addition to the base tuition amount, charters currently receive about $300 million for services to students with special needs. A select group of charter schools (those that are not housed within DOE buildings and that commenced operations or added grade levels in 2014–15 or later) share approximately $200 million annually to cover the cost of their leases. Both special-education and building-lease funds pass through NYC DOE’s budget to charters.

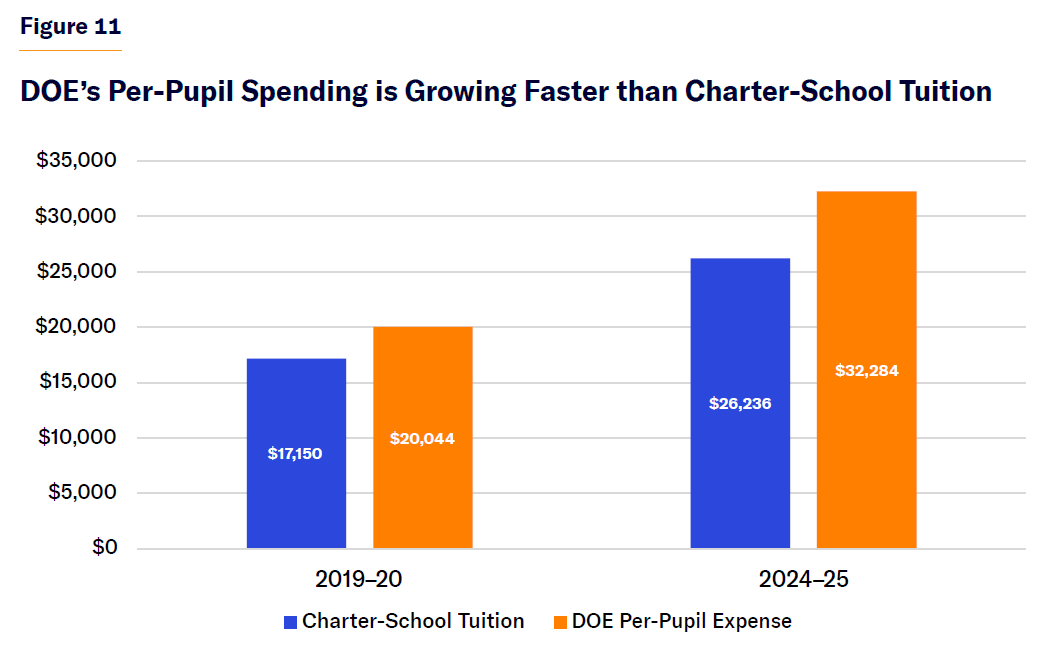

Since 2020, per-pupil spending in DOE schools (as computed by DOE) has grown by 23%. Charter-school tuition for NYC, set by New York State Education Department, has grown by 17% (Figure 11). (These two figures are not directly comparable in absolute terms, due to differences in the types and numbers of special-education programs in each sector and eligibility for lease assistance. But the differences in the rates of growth of these figures offer a useful comparison.)

Table 6

| Charter Schools | DOE Schools | |||||

| 2019–20 | 2023–24 | Change | 2019–20 | 2023–24 | Change | |

| Central Administration | 284 | 205 | –28% | – | – | |

| Classroom Teachers | 4,579 | 8,694 | 90% | 69,033 | 70,391 | 2% |

| Guidance Counselors | 225 | 270 | 20% | 2,360 | 3,045 | 29% |

| Other Nonteaching Staff | 914 | 1,419 | 55% | – | 3,085 | |

| Principals & Ass’t. Principals | 733 | 811 | 11% | 4,420 | 4,933 | 12% |

| Program Administration | 568 | 703 | 24% | – | – | |

| Psychologists & Psychiatrists | 55 | 6 | –89% | 994 | 1,182 | 19% |

| Social Workers | 215 | 239 | 11% | 1,033 | 1,903 | 84% |

| Grand Total | 7,573 | 12,347 | 63% | 77,840 | 84,539 | 9% |

| Total Student Enrollment | 128,951 | 144,889 | 12% | 934,109 | 833,181 | –11% |

Source: NYS Education Dept., Information and Reporting Services, Personnel Master File (PMF), updated Feb. 28, 2025

According to NYS Education Department, DOE added 1,743 new guidance counselors, psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers between 2020 and 2024, along with 1,358 new teachers and 513 new principals and assistant principals (Table 6).

By contrast, most growth in charter-school staffing came in the form of new teachers. Indeed, growth in the number of teachers at charters has eclipsed that of new students, leading to a 41% decrease in student–teacher ratio at charter schools. In DOE schools, the addition of new teachers, combined with an 11% enrollment decline, has led to a 13% decrease in student–teacher ratio.

Some differences in staffing trends between DOE schools and charter schools may be driven by the difference in the number and types of special-needs programs in the two sectors. But these trends also reflect policy choices made at DOE: namely, to emphasize social and emotional support through programs such as the community schools model and to maintain the size of its teaching force despite significant enrollment declines.

Ultimately, these trends illustrate the structural difference between a system that allocates resources without reference to student enrollment and one where funding is based solely on the number of students served, which is ultimately determined by the choices made by families.

In 2026, the mayor and school’s chancellor must consider how to better align school staffing with enrollment and with family preferences. Further, they must consider whether schoolchildren are benefiting from the emphasis on support services.

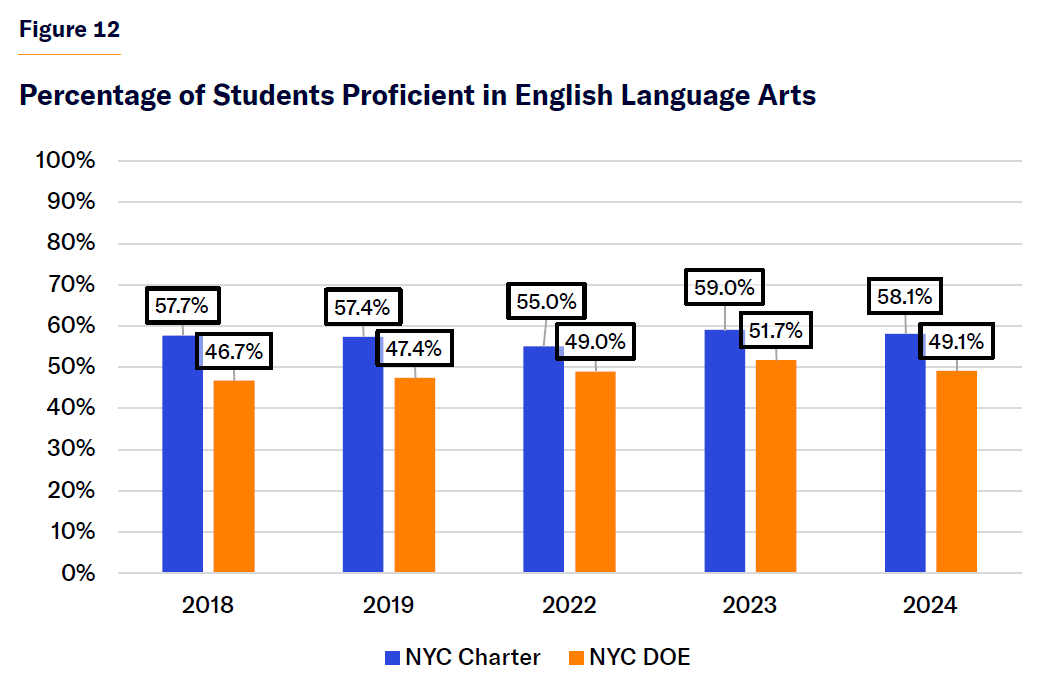

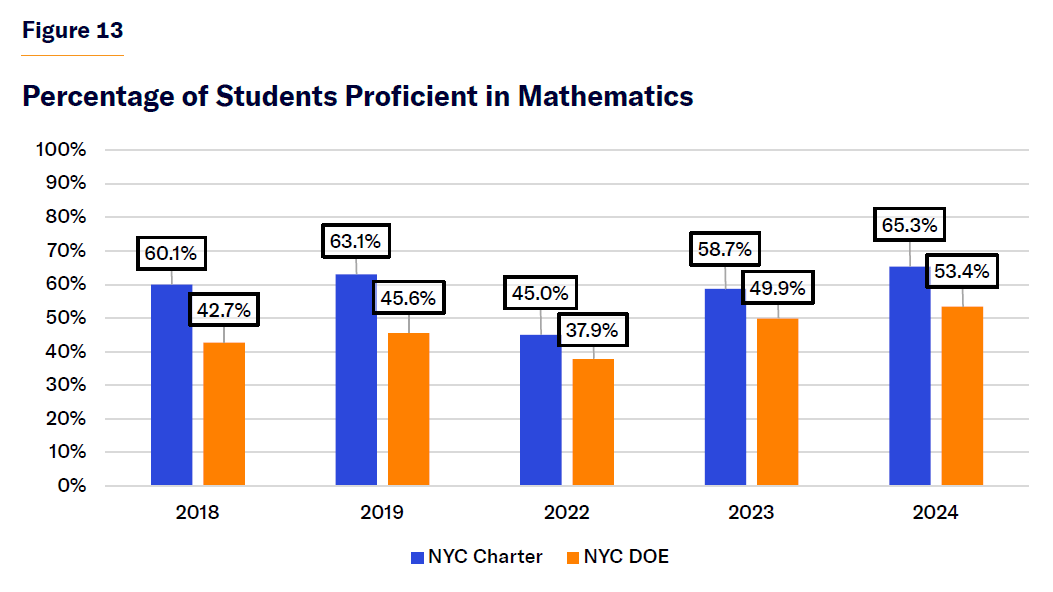

Charter-School Success

NYC’s charter schools consistently outperform DOE schools on annual NYS English language arts (Figure 12) and mathematics (Figure 13) tests; 89% of charter-school students are black (46%) or Hispanic (43%), compared with 62% of DOE students (19% black, 43% Hispanic).

Due to changes in the test, scores prior to 2023 are not comparable with those of previous years. (In 2023, NYS Education Department “recalibrated” the scores needed to demonstrate proficiency, which explains the resulting jump in both sectors from 2022 to 2023.) In 2024, charter schools outperformed DOE schools by 9 percentage points in ELA and by 12.1 points in mathematics.

NYC’s charter sector has been one of the strongest in the nation for the past 10 years. It has grown to serve 12% of the students in the city while continuing to offer a high-quality education and attracting more families every year.

Unfortunately, New York charter growth has slowed significantly. While the city’s charter schools have added 23,346 students in the past five years, only 1,001 were added in the last year.[3] Since 2010, a state law has established a cap of 460 charter schools statewide.[4] In 2023, there was a minor political deal to allow 14 charter schools to open in NYC to substitute for charters that had closed but were still being counted against the legislative cap.[5]

DOE’s budget currently allocates $180 million in city and state funding for charter-school leases.[6] But not every school is eligible for these funds. In 2014, the state passed a law requiring districts to offer co-locations or rental assistance to new charter schools. But schools established before this law are not covered. As a result, 75 charter schools in the city, with nearly 24,000 students, must cover their rent from the per-pupil funding they receive.

According to the New York Charter School Center, providing this assistance would cost less than $30 million this year; and in five years, it would represent less than 0.3% of the state’s education budget.[7] A bill currently in the New York Senate would address this inequality.[8]

With New York students facing challenges in the wake of the pandemic—especially the lowest-performing students, who have not made significant progress in the past few years—charter schools offer a promising option. According to an analysis by the director of the Arizona Center for Student Opportunity, Matthew Ladner, New York’s charter schools excel in helping low-income students achieve “basic or better” scores in eighth-grade math on the NAEP.[9] While only 39% of low-income students in NYC district schools achieved this benchmark in 2024, 64% of those in the city’s charter schools did so—the highest percentage in the country. Unfortunately, we lack sufficient data to conduct a similar analysis for reading.

Early Literature and Science of Reading

Young New Yorkers are struggling with reading: only 33% of fourth-graders read at grade level, according to the latest NAEP data—a decline of 4% since before the pandemic.[10] Additionally, state tests show that roughly 50% of students in grades 3–8 are not proficient readers. In 2023, Mayor Adams and Chancellor Banks launched the “New York City Reads” program, which supports the implementation of a curriculum based on the science of reading.

It is crucial that the new mayor continue to prioritize early literacy. Several schools that previously used outdated teaching methods, such as the three-cueing system, have shifted to a curriculum that incorporates sequential phonics instruction and emphasizes building knowledge to enhance reading comprehension skills. Chancellor Banks was a strong advocate on this issue, and the next chancellor should follow his lead.

NYC Reads has been promising but could be improved in one respect. The program offers elementary schools three curriculum options: Wit & Wisdom, EL Education, and Into Reading. The first two options are well designed. As Natalie Wexler notes in Forbes, these curricula include phonics instruction as well as content that will build students’ knowledge for reading comprehension.[11]

The Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy notes that this is important because:

in the early grades, students must be taught to read through the science of reading (e.g., phonemic awareness, the skills of decoding). But children also need simultaneously to learn about the world: its history, geography, science, myths, stories, and cultures. If they do not build meaningful content knowledge early on, students face a profound disadvantage in their later years of their education that will ultimately limit their professional and civic opportunities.[12]

But the third curricular option, Into Reading, falls short. According to literacy experts, Into Reading is “bloated,” with too many texts, some of which are low-quality.[13] Unfortunately, 22 out of 32 NYC school districts have chosen Into Reading, so rolling it back will be difficult. But doing so is necessary to ensure that NYC Reads delivers the improvements that we all expect.

The Myth of Class-Size Reduction

In 2022, the New York legislature passed the “Class Size Law,” which mandates smaller class sizes than those established under the UFT collective bargaining agreement. The law includes a timeline for implementation and imposes state funding penalties for noncompliance.

Chancellor Banks alerted the legislature about the impractical and unintended consequences of this law. He pointed out that the city lacks sufficient classroom space and qualified teachers to effectively reduce class sizes. Additionally, the cost of implementing this law would necessitate cuts to other school activities, such as arts programs and extracurricular classes. The minority report from the Class Size Working Group pointed out that the law primarily benefits high-income and high-performing schools, which are often the most overcrowded.[14] This could lead to fewer available seats in sought-after schools, such as SHSAT (Specialized High Schools Admissions Test) high schools.

The law is based only on the results of the Project STAR study,[15] which was conducted in the 1980s and purported to show benefits of class-size reductions. But its results have not been consistently replicated. Since the law’s passage, economists at the University of Pennsylvania published a new study highlighting concerns about Project STAR’s methodology and findings.[16] The authors note that the learning improvements observed in Project STAR were driven by only 29% of the schools in the data set, meaning that 71% of schools with reduced class sizes saw negligible results. Moreover, the schools that did see performance gains had only modest class-size reductions, while schools that implemented larger reductions did not see improvement.

This new study tracks the experience of California, which reduced class sizes in the 1990s: successful implementation is crucial.[17] If hiring qualified teachers is not feasible, reducing class sizes will only create more teaching positions without tangible outcomes for students.

The new mayor must renegotiate the Class Size Law to ensure that it is implemented in a fiscally and operationally responsible manner. The law should not apply to high-performing and in-demand schools, such as citywide programs and SHSAT high schools. Furthermore, the mayor should communicate the challenges and irrationality of implementing this law at present, especially given that the city has recently lost 200,000 students and per-pupil funding now approaches $40,000. Hiring additional unqualified teachers may lead to cuts in extracurricular activities and ultimately diminish the quality of education provided to students.

To comply with the law, DOE plans to hire almost twice as many teachers as usual for the 2025–26 school year (7,000–9,000, compared with an average of 4,000–5,000 new hires per year).[18] Inevitably, some of these additional teachers will be underqualified, and the money spent to hire them may lead to cuts in extracurricular activities—cuts that ultimately diminish the quality of education provided to students.

Outside Influences

Across the nation, schools today have to contend with negative forces outside their control. Social media and smartphones, for example, harm children’s willingness and ability to read and contribute to emotional and social problems that families and schools must deal with. NYS’s recent legalization of recreational cannabis also harms learning in schools.

Most students in school today were born after 2010, when the smartphone boom began to allow for constant access to social media and online information. Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has documented how these technologies have contributed to a rise in adolescent depression and anxiety, among other mental-health and social issues.[19] Educators report that smartphone usage during school hours has caused disruptions to student engagement during the school day.[20] New York has joined other states in moving toward a ban on smartphone usage in schools.[21] That is an encouraging step, but NYC must commit to enforcing this ban rigorously.

Social-media usage outside school also negatively affects schools when it includes bullying or racial and ethnic hatred. City schools are not immune to these ills, and there are no easy solutions. DOE needs to incorporate reasonable limits on such damaging behavior as part of school behavior codes to discourage bias and bullying within school communities.

NAEP data indicate that the percentage of students (at age 13) who report reading for fun on their own time is at all-time lows since data were first collected in 2012.[22] In 2023, 14% of 13-year-olds reported reading for fun “almost every day,” down from 27% in 2012. Some 47% said that they read for fun “a few times a year” or “never or hardly ever.” The mayor should consider a multiagency campaign, including libraries, child-care centers, and other youth-serving organizations to encourage and support frequent reading on the part of the city’s schoolchildren.

Legalized cannabis has also posed challenges. As reported in Chalkbeat and the New York Times, educators in New York City are reporting that “more and younger” students are consuming cannabis before school and during the school day since NYS legalized recreational use in 2021.[23] Though the law intended to limit cannabis sales to state-licensed shops, the city has become inundated with unlicensed shops, including many in proximity to schools. Some have suggested that students are “self-medicating” to deal with undiagnosed mental-health issues, but educators note that students showing up “late and high” exacerbate classroom disarray.

These outcomes are the result of the legislature’s decision to legalize cannabis, as well as the district attorneys who have chosen not to prosecute unlicensed sales. The mayor should engage police and other departments in a drive to create safe, cannabis-free zones around schools.

Recommendations for the Next Mayor’s Education Team

The next mayor must act quickly and forcefully to ensure that NYC’s schools are responsive, accountable, and focused on students and their needs. Four key aspects should form part of their agenda: strengthening the system; expanding educational choice and innovation; Albany advocacy; and a family and community focus.

Strengthening the System

- Install a strong leadership team at DOE. To do so, the mayor should look outside the school system and consider candidates from the city’s successful charter schools or successful leaders from outside the city. A new vision is needed at Tweed Courthouse. In choosing a chancellor and making appointments to the Panel for Education Policy, it is important that the mayor select individuals who share his/her vision of education and are committed to acting solely in the interest of the city and its schoolchildren. These leaders must look beyond the demands of the myriad ideological and employee interest groups surrounding the system. Instead, they should listen to the very clear demands that families make through their choice of schools and their own advocacy. Oversubscribed programs should be expanded and underutilized schools and programs pared back. To facilitate family choice, the system’s leadership must be committed to high achievement and a pluralistic approach to the system’s courses of study for college-bound students and those seeking workforce preparation. The system should provide easy-to-understand assessments of school and program performance.

- Focus on the real causes underlying the school system’s current low performance, not false excuses such as the lack of resources or whatever changes emerge from the ongoing redirection of federal education efforts.

- Make clear that schools will be held accountable for student performance—and that more funding comes with more responsibility. Bring back easy-to-understand letter grades for schools and pledge to act on those schools with low grades. Over the last 12 years, the city has moved away from this commonsense approach by scaling back public reporting of school performance and de-emphasizing the importance of student achievement. Given decreased enrollment in DOE schools, school consolidation—based on performance—is called for.

- Given the huge decline in DOE enrollment over the last 20 years, many local school districts have few students; 10 of the 32 districts educate more than half of all students enrolled in pre-K through eighth grade. There are also many schools with too few students to be effective. DOE should emphasize that priority will be given to services that are known to be effective. Over the last two administrations, the number of guidance counselors, social workers, and school psychologists and psychiatrists has increased, with little evidence of success. DOE must accelerate its efforts to consolidate underutilized schools.

- Cell-phone usage in school and social-media usage outside school are now recognized as harmful to young people. The city’s schools must rigorously enforce the new ban on cell-phone usage in schools and must look for ways to reduce bullying and intergroup conflict as part of their behavior and discipline policies.

Expanding Educational Choice and Innovation

- Focus on creating a more pluralistic system, with merit-based admissions to high schools and middle schools available in all communities. Working with educators and outside partners, expand access to high schools dedicated to following industry standards and to preparing students for entry-level positions directly out of high school.

- Increase the number of seats in specialized high schools—those that use the SHSAT for admissions—in two ways: increase the size of the newest and smallest SHSAT schools; and consider creating a new SHSAT school in Queens, where demand remains high for this type of high school.

- One-third of the city’s schoolchildren are educated outside DOE schools. Some 240,000 are in private and religious schools, 140,000 are in charter schools, and 17,000 are being homeschooled. These families are still constituents who need to know that the mayor will support their choices. DOE currently provides support services, including pupil transportation, school meals, and Title I funded instruction to eligible private and religious schools. The system should provide those services efficiently and with respect for the specific needs of individual schools. In the case of the Haredi boys’ schools, which have come under scrutiny by NYS Education Department, DOE should assist these schools in hiring well-qualified and trained Title I teachers (in eligible schools) while the state’s challenge to their curriculum is sorted out by the judicial system. The city should continue to promote safe and orderly streets around private and religious schools, in addition to public and charter schools.

- The city’s growing number of schools serving Haredi communities are under threat of state sanctions because of their traditional curriculum. The issue is currently in the courts and is more complex than the critics of these schools have alleged. Families using these schools should know that the city values them and their right to practice their religion as they see fit.

Albany Advocacy

- The legislature and city council have insisted that DOE’s budget continue to grow as enrollment has declined. The mayor should argue that some of that money would be better spent outside the school system to support families with social, housing, and other needs.

- The mayor should push the legislature to remove the cap on the creation of charter schools in the city and support expanding lease assistance to the 75 charter schools that existed before the 2014 law that required such assistance. Those schools are being unfairly penalized.

- Ask the legislature to reconfigure the Community School District system to make it more effective and efficient.

- Urge the legislature to rescind the class-size reduction law.

- The current structure of the Panel for Educational Policy (PEP)[24] hampers the implementation of reforms in NYC’s public schools and limits mayoral control over crucial policy decisions. Currently, the panel comprises 24 members, a number that is not only excessively large but also an even number, which makes it difficult to make decisions on controversial votes. Moreover, Albany’s control over the selection process for the chairperson is problematic. According to law, the mayor must appoint the chair from a list of three candidates nominated by the Speaker of the Assembly, the Majority Leader of the Senate, and the Chancellor of the Board of Regents.[25] To improve efficiency and effectiveness, the size of PEP should be reduced to 11 members, with six appointees chosen by the mayor and one appointed by each borough president. Additionally, the mayor should be granted the authority to select the PEP chairperson directly.

A Family and Community Focus

- Mount a citywide campaign to remind parents about the importance of regular school attendance. Assure families that their public schools are focused on the needs of their children and that they must do their part to ensure that students are present and prepared to learn. Focus particularly on the early grades, to see that good habits are instilled early. Engage multiple city agencies in health and social services to address the problem of chronic absenteeism.

- Ensure that the streets around schools are safe and orderly. Focus on quality-of-life issues, including the sale of cannabis and drugs in proximity to schools. Maintain a police presence where necessary to ensure student safety.

- Base your education agenda on the needs of today’s students and families, who differ greatly from earlier generations in terms of ethnicity and social and immigration status. In DOE’s elementary and middle schools, Hispanic students are the largest group by far. Asian students are the second-largest and white students are the third-largest group. Build support for your program among all groups in the city. That begins with really listening to them.

- The city has become less hospitable to child-rearing families in ways outside the control of schools. Affordability is driving families outside the city. Adopt a pro-growth housing program to increase access to affordable housing for all income groups.

About the Authors

Ray Domanico is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. His career has spanned the public and non-profit sectors, in research and advocacy roles. Most recently, Domanico was director of education research at New York City’s Independent Budget Office, where he led a team tasked with studying and reporting on the policies and progress of America’s largest public school system. Previously, he served as senior education advisor to IAF Metro NY where he worked with local leaders and educators to design and support a small group of new district high schools and charter elementary schools. Domanico began his career in research positions in the New York City school system, and he has taught graduate-level courses in educational research and policy analysis at Brooklyn College and at Baruch College. Domanico holds an MPP (master of public policy) from the University of California, Berkeley.

Danyela Souza Egorov is a writer, education policy expert, and advocate for school choice. She has over 10 years of professional experience in business, government, and nonprofits, with a focus on strategy, advocacy, and management. Danyela started her career as a management consultant at McKinsey & Co. She holds an MPP from Harvard Kennedy School and was the founding board chair of Brooklyn RISE Charter School. She is currently the secretary of CEC 2 and the founder of Families for NY. Danyela’s articles and op-eds have been published in the New York Post, City Journal, and New York Sun. She has appeared on TV several times and has and testified twice to the U.S. House of Representatives.

Endnotes

Photo: kolderal / Moment via Getty Images

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).