Executive Summary

Permanent supportive housing (PSH) has become a central part of the government’s response to homelessness. PSH, which provides rental assistance coupled with social services, is prioritized for “chronic” cases: those with a disability and a long-term experience of homelessness.

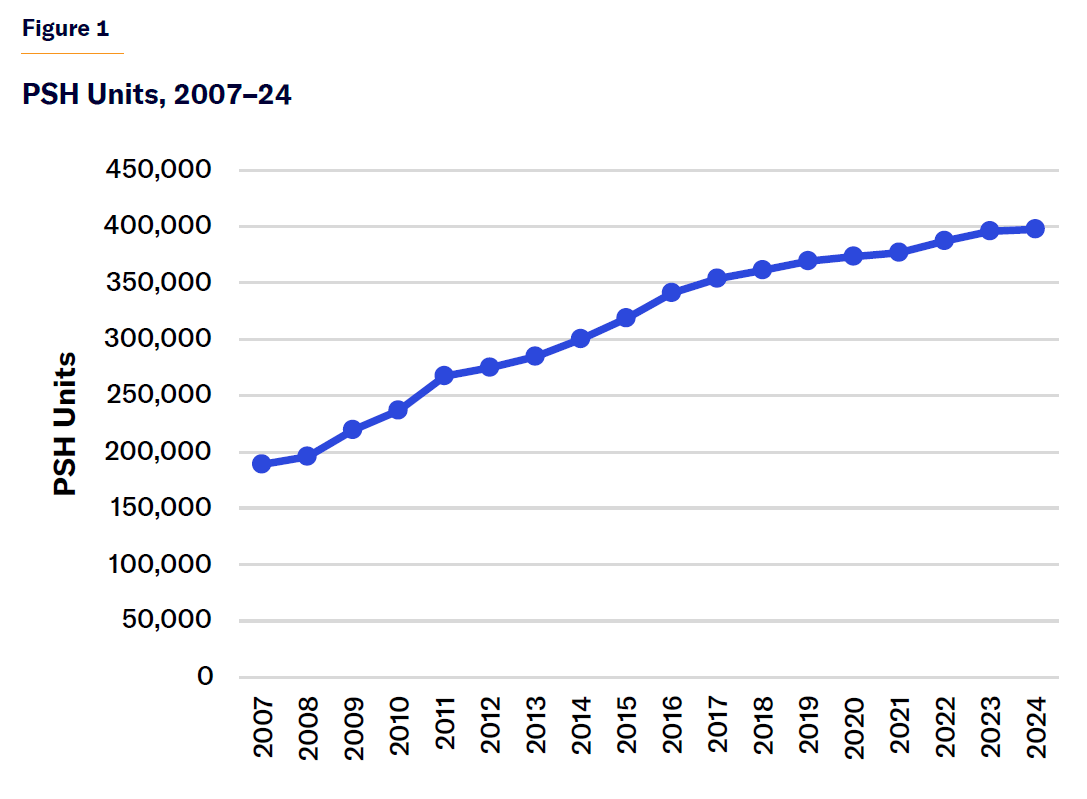

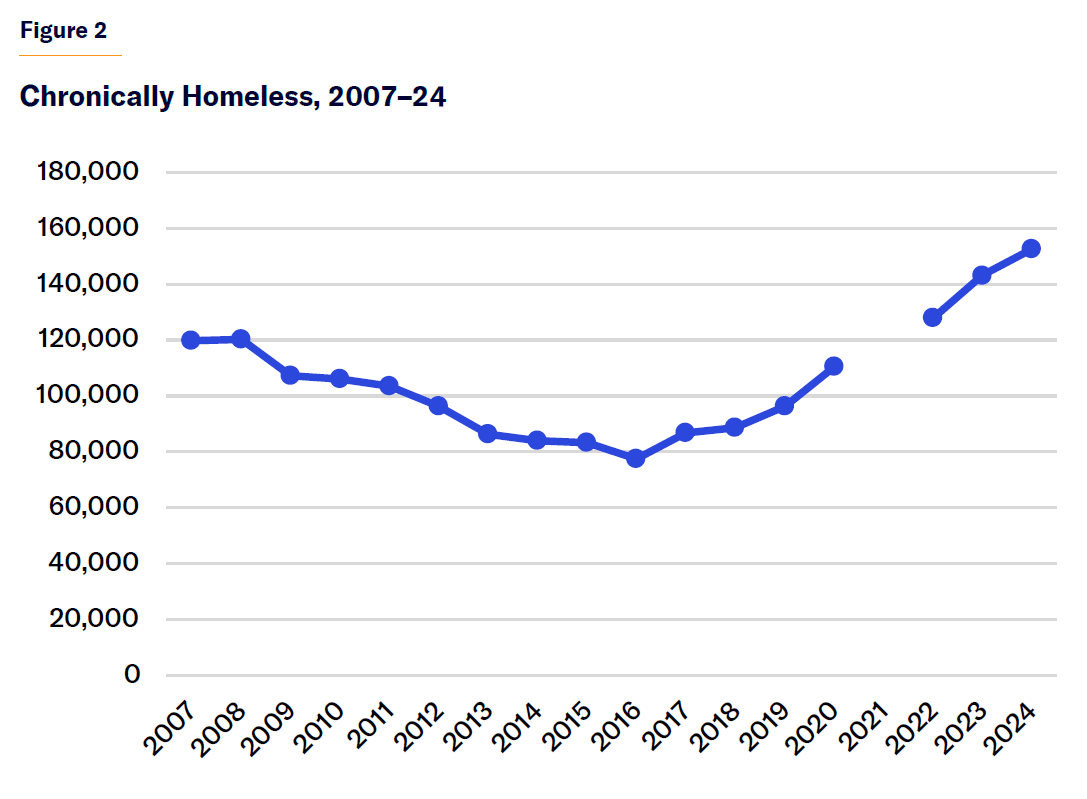

There are around 400,000 PSH units nationwide, up 25% over the last decade. That increase reflects policymakers’ embrace of the Housing First philosophy, which emphasizes permanent housing as the solution to homelessness. Proponents of these policies claimed that they would dramatically reduce, or perhaps even end, homelessness. But homelessness reached a record high last year, exceeding the record high of the previous year.[1] Chronic homelessness, too, is at a record high.[2]

Smart Policy, Straight to You

Don’t miss the newsletters from MI and City Journal

The Trump administration has indicated that, given these failures, it will reassess the place of PSH in federal homelessness policy.

That reassessment is appropriate, especially because the PSH model will face even more challenges in the coming years. Problems inherent in PSH that were ignored during its rapid growth will become more acute and hinder further expansion:

- PSH budgets will have to divert more resources to maintain old units, thus reducing resources for adding new units.

- PSH’s emphasis on community integration creates community opposition, which slows the rate at which new units can be brought online. Community opposition will increase in coming years.

- PSH is hard to scale, and its effect on homelessness, which is limited to begin with, fades over time. That will weaken public support for the model.

- Some PSH tenants need a higher level of care than the model can deliver.

Reassessment is not the same as replacement. PSH will continue to play an important role in government’s response to homelessness. To strengthen current PSH programs, this report concludes with the following recommendations:

- Decouple PSH and Housing First by giving PSH providers more flexibility.

- Invest in temporary housing.

- Create treatment courts for housing.

- Shift more responsibility for the most difficult PSH tenants to other behavioral health systems.

Introduction

In some places, such as California, homelessness has consistently ranked among top public concerns since the 2010s.[3] In response, policymakers have prioritized investment in permanent supportive housing (PSH), or service-enhanced housing for the homeless.

At the end of the Biden administration, federal outlays on homelessness had reached historical highs.[4] There has also been an impressive increase in state and local commitments to housing for the homeless.[5] In total, Los Angeles’s HHH program (2016), New York City’s NYC 15/15 initiative (2015), and New York State’s Empire State Supportive Housing Initiative (2015) will build more than 40,000 units of PSH. The nation’s PSH stock has increased 25% since 2014 (Figure 1).

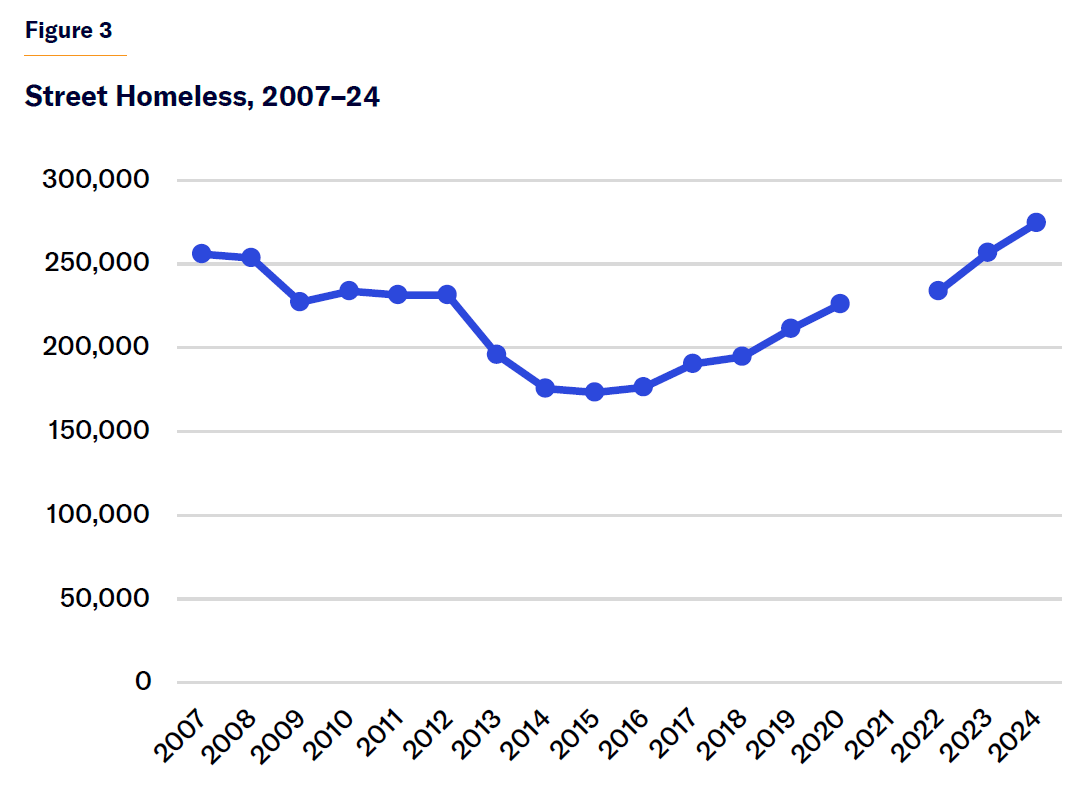

But the case for even more spending on PSH has weakened recently because, despite historical investment in the model, rates of homelessness have risen to record-high levels. Some of that surge has been driven by the recent increase in migrants, many of whom were placed in shelters.[6] But the number of unsheltered and chronically homeless people—who are a priority for PSH placement due to disability and long-term homelessness—is also at a historical high. Independent of the migrant surge, New York and California have long been grappling with homelessness crises, despite their investments in PSH (Figures 2–3 and Table 1).

Table 1

PSH Expansion vs. Change in Homelessness, 2007–24

| # Change, 2015–24 | % Change, 2015–24 | |

| Nationwide | ||

| PSH Units | 78,568 | 24.7% |

| Street Homeless | 100,956 | 58.3% |

| Chronically Homeless | 69,415 | 83.5% |

| California | ||

| PSH Units | 27,998 | 55.2% |

| Street Homeless | 50,275 | 68.2% |

| Chronically Homeless | 37,370 | 128.1% |

| New York | ||

| PSH Units | 12,491 | 31.3% |

| Street Homeless | 1,616 | 40.2% |

| Chronically Homeless | 750 | 17.3% |

PSH expansions have been guided by a theory known as Housing First, which holds that permanent housing benefits must be granted without requiring participation in services, sobriety, or any other behavioral change. In Housing First–style PSH, social services are provided on a purely voluntary basis. Some PSH programs began before the development of Housing First.[7] However, at present, Housing First and PSH are functionally indistinguishable.

Problems That Will Hinder Further PSH Expansion

Over the last two decades, Housing First has gained influence among major government funders of homelessness programs, such as the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Continuum of Care program and the California state government. Policymakers—and, to an extent, the broader public—believed advocates who claimed that Housing First could end homelessness. But because the jurisdictions that most thoroughly implemented Housing First have seen large increases in homelessness, skepticism about the policy is growing. With national homelessness trends now so unfavorable, a reassessment of Housing First is unavoidable. In its FY26 budget request, the Trump administration called for restructuring homelessness assistance grants as mainly temporary housing.[8] While the final results of the budget process are uncertain, the proposal is evidence of the administration’s intent to redirect homelessness policy away from Housing First.[9]

A thorough reassessment of homelessness policy should also examine the PSH model—including its inherent problems, which were ignored as the model expanded and are likely to worsen in coming years. Faced with such an assessment, even the policymakers most ideologically committed to PSH and Housing First would have to accept the fact that expansion will be even harder than in the past.

Expansion vs. maintenance

PSH exists in two forms: tenant-based, in which the subsidy is given to the individual who uses it to rent a unit on the private market; and site-based, in which the subsidy is connected to a unit. Most PSH stock is tenant-based, especially outside New York and California (Table 2).[10]

Table 2

Tenant-Based vs. Site-Based PSH, 2024

| Total PSH Nationwide | 412,623 | |

| Tenant-Based PSH, Nationwide | 248,241 | 60.2% |

| Site-Based PSH, Nationwide | 164,382 | 39.8% |

| Total PSH, California and New York | 135,209 | |

| Tenant-Based PSH, New York and California | 53,078 | 39.3% |

| Site-Based PSH, New York and California | 82,131 | 60.7% |

| Total PSH, Outside California and New York | 277,414 | |

| Tenant-Based PSH, Outside California and New York | 195,163 | 70.4% |

| Site-Based PSH, Outside California and New York | 82,251 | 29.6% |

Some homeless advocates favor tenant-based PSH because it provides the homeless with ordinary housing: a normal rental unit like one that any other household might use, integrated into buildings and neighborhoods inhabited by the non-homeless.[11] Orthodox Housing First doctrine holds that “consumer choice” is paramount and that, given the choice, homeless Americans would prefer to “live in a place of their own rather than in congregate specialized housing with treatment services onsite.”[12] The dominance of tenant-based PSH is also in line with broader norms in affordable housing, which have, over the years, shifted toward voucher-style approaches.[13]

However, tenant-based PSH has certain practical disadvantages. Expanding tenant-based PSH, at scale, requires getting more landlords to enter the business of housing the formerly homeless. NYC 15/15 was initially projected to create 7,500 units of site-based PSH and 7,500 tenant-based units. But with too few landlords willing to participate, the city recently announced that most of the tenant-based units would be converted to site-based.[14] The problem is especially acute in hot housing markets, which pose the greatest risk of homelessness for low-income individuals but which also offer landlords the widest choice of tenants. As a result, tenant-based PSH is particularly hard to scale in places where it is seen as most needed.

Relying on landlords also subjects PSH tenants to greater risk of eviction. Formerly homeless people are more likely to engage in behaviors that can lead to eviction, including nonpayment of rent,[15] hoarding,[16] setting fires, flooding, noise, harassing other tenants, assaulting other tenants, and “unit takeovers,” ceding control of a unit to a drug dealer or someone else interested in using it for criminal purposes.[17] Some studies of tenant-based PSH programs show extraordinarily high rates of housing instability.[18] While eviction may sometimes benefit other tenants, it is easier to control in the case of site-based PSH.

But site-based PSH also faces practical difficulties. Like mainstream affordable housing programs, site-based PSH developments rely on multiple funding sources, such as the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (a block grant–style federal program available to states),[19] own-source state and local housing programs, and population-specific resources such as for veterans and tenants with AIDS. However, the extremely low incomes of PSH tenants and the need for service funding make financing these projects especially expensive and complex.[20]

In 2023, the Los Angeles–based Skid Row Housing Trust, a major site-based PSH provider, fell into receivership.[21] Beginning in the late 1980s, the organization built a strong reputation by acquiring derelict for-profit hotels in Skid Row and renovating them into nonprofit PSH. Over the years, Skid Row Housing Trust grew its portfolio by tapping into various new funding streams—but it also failed to maintain its older properties. By 2022, a quarter of its 2,000 units were vacant, often due to severe damage, triggering a vicious cycle of declining rent revenues and further deterioration.[22] Because each property relied on different funding streams, money dedicated to viable properties could not be used to repair damaged units. The severity of the situation was not evident before receivership because the trust’s financial statements reported the condition of the organization as a whole, not individual properties. Its portfolio of 29 buildings was sold off to new owners whose goal is to maintain all units as PSH, but finances remain precarious.[23]

The downfall of Skid Row Housing Trust reflects a classic pathology of American government: prioritizing expansion over maintenance. Faced with a homelessness emergency, the city of Los Angeles rushed to bring new housing units online. The city’s voters approved historical levels of investment in PSH, including via the $1.2 billion HHH program in 2016, in which the trust participated.[24] Policymakers devoted less attention and resources to maintain existing programs.

The Skid Row Housing Trust began around 1990, when many other PSH programs were launching.[25] Examples of other once-admired supportive housing providers now facing financial problems are the San Francisco-based Tenants and Owners Development Corporation and the Chicago-based Heartland Alliance. In NYC, some older PSH projects currently have more than 100 building violations,[26] while more than 2,000 PSH units are currently offline because they are too damaged to rent.[27]

All landlords rely on rents to fund upkeep, which is especially challenging for PSH. Low-income households not only pay less in rent than working-class and middle-income Americans, but their payments are also more erratic.[28] Rent delinquency is a major concern for many PSH providers.[29] Meanwhile, as PSH building stock continues to age, so do the tenants,[30] which will require expensive accessibility-related maintenance.

To promote community integration, PSH is meant to resemble normal community living, not institutional living. Residents can come and go as they please, without being subject to any more requirements than a typical tenant. Best-practice manuals, such as a 2010 report published by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, advise against “clustering” PSH tenants.[31] The pursuit of integration, however, often provokes community opposition, which critics term “NIMBYism” (Not in My Backyard-ism).

PSH prioritizes those who have experienced long-term homelessness, without imposing any expectation of behavioral change. Thus, asking a neighborhood to accept PSH is a different proposition from, for example, asking it to accept a family shelter, affordable housing project, or market-rate apartment building. Individuals whose behavior in tent encampments provoked community outrage do not necessarily become ideal neighbors after they are placed in housing.[32]

Working-class and low-income neighborhoods[33]—which often welcome forms of development that wealthy areas reject, such as affordable housing—are less receptive to programs like PSH, single-adult shelters, methadone clinics, and safe consumption sites. Residents of these areas feel that they are already “saturated.”[34]

Over the past two decades, cities such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York have expanded not only PSH but also a broader array of programs serving those with addiction, seriously mental illness, and criminal records. As a result, more neighborhoods can now credibly claim to be saturated than when PSH expansion started.

Even when funding is available, community opposition slows down the pace at which government can bring units online. If opposition remains high, inflows into homelessness are likely to outpace the number of people housed in PSH.

Scale and fadeout

PSH is hard to scale. The peer-reviewed literature on PSH/ Housing First largely examines rates of residential stability among formerly homeless people placed in PSH. In these studies, residential stability rates typically hover around 80% over the course of the study—usually less than five years.[35] However, these findings reflect outcomes of individual programs, not the effects of Housing First implemented at a community-wide scale. One 2017 study found that reducing homelessness by a single person may require building as many as 10 PSH units.[36]

A major PSH expansion will absorb a certain portion of a community’s homeless population. But after all those units are leased, what happens to new people who fall into homelessness? Over a period longer than a few years, many homeless people who do not get PSH will exit homelessness, and some homeless people who do receive PSH will wind up homeless again.[37] Thus, the effect of PSH, over and against other interventions, fades over time.

Scale- and fadeout-related problems mean that even dramatic investments in PSH might not yield noticeable and sustainable improvement in street conditions. That has certainly been the experience in California, where public support for PSH has weakened.[38] Advocates can still argue that expanding PSH is the right thing to do—but they can’t argue that members of the public will notice a change in their quality of life.

Health vs. housing

PSH differs from mainstream affordable housing most distinctly in its promise of supportive services. But those services can be expensive: per unit estimates of annual PSH costs range from less than $20,000 to over $50,000.[39] Some providers argue that they have been underfunded.[40]

These requests for more money may reflect unreasonably low funding rates for old programs and how, in recent years, government required PSH providers to accept tenants with increased behavioral and health problems, who are more expensive to handle.[41] It’s also possible that funding rates were consciously set too low, in order to build political support for PSH and the idea that it was the most cost-effective solution to homelessness.[42]

PSH is prioritized for the chronically homeless, whose needs are among the most acute within the homeless population generally—which itself has some of the highest needs among all low-income groups. Meeting these needs might require an array of nurses, case managers, professionals who specialize in supported employment (via social enterprise or corporate responsibility programs), staff for art and music programs, fitness and nutrition specialists, mental-health professionals (psychiatrists, clinical social workers), and substance-abuse professionals (detox, medication-assisted treatment, peer support). Whether, or to what degree, investment in these services is appropriate depends on whether PSH is appropriately defined as a health or housing program.

The argument for increased spending on supportive services is, to some extent, similar to that for greater investment in maintenance of existing units. But spending on basic maintenance does not raise questions about the ultimate goal of PSH. If residential stability is the only standard of success in homelessness policy, only a modest level of supportive services is appropriate.

Residential stability can also be achieved by simply not evicting tenants for behavior that would normally merit that course of action. In the case of some tenant-based PSH programs, supportive services functionally serve the landlord,[43] who expects to have someone to call when friction arises. Supportive-services personnel intercede with, and on behalf of, landlords and find new housing situations when existing ones become untenable. Supporting landlords is an important goal.[44] But it is different from improving the health of formerly homeless tenants. If PSH “service” funds serve only to manage friction with landlords, it is not obvious why these funds should qualify for Medicaid reimbursement.[45]

Some proponents of PSH obscure questions about the program’s purpose by equating investment in housing with investment in health care. But the Housing First literature reveals high rates of social isolation and mortality,[46] as well as poor health outcomes,[47] among participants. These outcomes suggest a deeper problem: PSH programs are effectively warehousing those with complex needs in environments that cannot provide adequate care.[48] Several journalistic accounts have detailed how PSH can become gruesome for tenants who need more care than the programs provide.[49] While some argue that establishing and maintaining housing is in itself therapeutic—or at least helps to socialize—that is less true when tenancy requires fewer expectations.

Perhaps more spending on supportive services would improve health outcomes for some PSH tenants. But for tenants with the most acute, unmet needs, the focus should be instead on finding a program that provides a higher level of care than PSH—for their own benefit, as well as that of other tenants and the host neighborhood.

Recommendations

The recent rapid expansion of PSH was premised on a flawed assumption: that homelessness was immune from normal dilemmas encountered in other fields of social policy. The problems facing PSH—expansion vs. maintenance, scale and fadeout, NIMBYism, community opposition, and the failure to distinguish between health and social needs[50]—are familiar. Infrastructure and public housing struggle with maintenance; alternatives to incarceration and charter schools confront scaling problems; pre-K programs face fadeout; and addiction services regularly provoke NIMBY backlash. The belief that homelessness was somehow exceptional in its avoidance of normal policymaking pitfalls fed an even more flawed assumption: that homelessness could be ended.

Funding for federal homelessness programs is unlikely to rise dramatically in the near-term. At the state and local levels, homelessness-related ballot initiatives have recently been passing by slimmer margins than they did during the 2010s.[51] Increased fiscal restraint, combined with the challenges facing PSH, means that even policymakers who are philosophically committed to Housing First will have to consider alternatives in the coming years.

The growth of Housing First was driven, in part, by exaggerated claims about its effectiveness[52] but also by a legitimate desire for permanent housing solutions to homelessness on the part of many American communities. This need can be exaggerated, but it is real. What communities want is not an end to PSH but the freedom to operate it as best they see fit.

Reassessing PSH should, above all, be focused on consolidating and improving current programs. Here are some recommendations about how to relieve pressure on PSH providers:

Decouple PSH and Housing First by giving PSH providers more flexibility

Provider flexibility could be expanded by loosening requirements in the “Notice of Funding Opportunity” for HUD’s Continuum of Care program or by block-granting the Continuum of Care program.[53]

With more flexibility, PSH providers would be able to:

- Require that tenants take their medication (as happened in some PSH programs before the advent of Housing First),[54] pass drug tests, or show up for social- and health-services appointments

- Use probationary housing—i.e., require that tenants stay in their unit for a few months before they acquire standard tenant protections

- Impose stricter rules on some tenants

- Pursue more integration with behavioral health programs that use incentives and coercion, such as assisted outpatient treatment or contingency management

- Use homelessness funds on sober-living or recovery housing programs

A program that imposed behavior rules, provided housing on a probationary basis, and asked more of some clients than others could still be meaningfully considered service-enhanced or supportive housing. The goal would be to create housing for the homeless that expected recovery and personal transformation, as opposed to just allowing for that possibility.

Greater rule enforcement will help reduce community opposition. A program that imposes behavioral requirements on tenants will provoke less backlash than one that asks nothing. It may also help to lower capital needs, as tenants with unaddressed behavioral health disorders will do more damage to units than stabler tenants.[55]

PSH programs should also have more flexibility over tenant selection. In the current “Coordinated Entry” approach, governments allocate PSH units based on who has been homeless longer and struggles the most with mental illness and addiction. This approach has three problems. First, it rewards drug addiction;[56] it is overly bureaucratic, leading to long waits to fill vacancies, which, in turn, lead to disruptions in rent revenues; and it has burdened providers with tenants who are too difficult to manage.[57] Coordinated entry was adopted partly to prevent providers from cherry-picking or “creaming” their tenants. But any well-designed social-services system gives the provider some degree of selectivity over its clients.[58]

More flexibility is imperative in an era of flat funding. One of the most misleading arguments for Housing First to gain traction was that housing without rules is cheaper than the alternative. Some advocates say that rules will reduce the uptake of services because conforming to rules will be a deal-breaker for many members of the street population. But regulated housing programs tend to be safer—which always ranks as a top priority in surveys of the unsheltered—and, when there’s more demand for PSH than supply, which is normally the case, providers have leverage. Rules-oriented PSH will not lack for takers.

Changes to federal homelessness policy will affect different communities differently. Wealthy, big-spending jurisdictions, such as New York and California, will be the least affected. The typical U.S. community devotes very little own-source revenues to homelessness-specific programs. But all would appreciate more flexibility. The end of Housing First need not, and should not, mean the end of PSH.

Invest in temporary housing

Since 2007, PSH and other permanent housing programs have grown 260%, whereas shelter and other temporary housing programs have increased only 20%.[59]

An unrealistic belief that government can solve homelessness through permanent housing has left many homeless individuals without access to any kind of housing. PSH as currently structured is highly perfectionist. It attempts to end homelessness by providing housing in units that cost as much as $800,000 and require a years-long wait on the street to secure.[60] Those living on the streets should not be encouraged to hold out for perfection.

Shelter is less of an all-or-nothing proposition than PSH. It is much easier to bring shelter beds online quickly than PSH units. If it is true that “housing is health care,” that is just as true for temporary as for permanent housing. Shelter takes someone off the streets, provides food and a place to sleep and store belongings, and offers connection to other services. Shelter is much safer than the streets.[61] Studies of homeless mortality have found disproportionately high mortality rates among the unsheltered population.[62] The rate of sexual assault and trauma for homeless women, especially the 84,000 unsheltered among them,[63] is very high. Building more shelters is by far the most efficient way to protect them.[64] The most truly pragmatic, “greatest good for greatest number” approach to homelessness would be shelter-oriented, not PSH-oriented. When someone does access PSH, he’ll be able to benefit more from it—and place less pressure on the program—if he has spent the previous months in a shelter instead of on the streets deteriorating.

Homelessness policymaking requires managing flows. Every day, some Americans fall into homelessness and others move out. But people don’t fall into chronic homelessness so much as transition into it from episodic homelessness. Not investing in temporary housing, because all the funding is tied up in PSH, risks undermining these individuals’ motivation, thus leading more non-chronic cases to become chronic ones.

Create treatment courts for housing

Courts are commonly used to effect behavioral change. Examples include problem-solving criminal courts and family court.[65] Setting up a similar program within housing court would allow providers to use the eviction threat as leverage—something they already do—but through a more formal process. A housing court–based treatment program would begin eviction proceedings, and then divert tenants into a drug or mental-health program to avoid eviction. The goal would be to replicate the success that sober living and contingency housing programs have had in promoting behavioral health, but within the PSH context. Behavioral health resources would be required to divert tenants into these programs, which will be more robust in some communities than in others.

Shift more responsibility for the most difficult PSH tenants to other behavioral health systems

The health needs of some formerly homeless PSH tenants cannot be met by current programs. Those needs should be dealt with by transferring responsibility for them to mental-health or addiction-services authorities, rather than adding more social- and health-services enhancements to current PSH programs.

The best argument for Housing First is that it is hard to repair broken lives, and, for those who are homeless, not much seems to work other than housing.[66] However, outside the homelessness context, there are evidence-based programs for rebuilding broken lives. Examples include supported employment and other vocational services,[67] full-service partnerships,[68] clubhouses,[69] first-episode psychosis interventions,[70] special court programs (problem-solving courts like mental-health courts[71] and HOPE-style desistance mandates[72] ), reentry programs,[73] sober-living housing programs,[74] 12-step addiction programs,[75] contingency management,[76] and assisted outpatient treatment.[77] At homelessness conferences and in strategic planning documents, these programs tend to be eclipsed by interest in the technical details about how to fund and build more PSH. These programs are operated by other agencies—criminal justice, addiction, mental health—outside homeless services and thus are evaluated based on a different standard from residential stability. While PSH’s goal of residential stability might be appropriate for some cases, other tenants would benefit from being placed in a program with different goals. In those cases, the resources should follow the tenant. In the debate about “criminalization of mental illness,” there is broad agreement that the criminal-justice system is the wrong place for many mentally ill people. This idea of a “category error”[78] also applies to homeless services.

Conclusion

We are entering an era of consolidation for PSH. To a greater extent than in the last two decades, governments will now have to focus on the quality of current programs as much as the raw quantity of units. Expansion can no longer be the only priority.

To promote a reassessment of PSH and Housing First, the federal government must adopt a more deferential role in homelessness policymaking. In contrast to other policy areas, such as higher education, federally directed homelessness reform will not require using funding as leverage to force change at the state and local levels. Homelessness represents a case in which recipients of federal funding deserve more programmatic flexibility than they have recently experienced.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Moynihan Center at The City College of New York, and, for their comments on the draft, Dan Kent, Paul Webster, and Judge Glock.

Endnotes

Photo: Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).

Source link