Israel’s and America’s attacks on Iran may prove pivotal for the Middle East if all the blows the clerical regime has absorbed since October 7, 2023, lead eventually to the collapse of the Islamic Republic. If the theocracy remains, however, or if an Islamist military dictatorship replaces it, the picture is a little different: Sunni-ruled Syria and its ally, Turkey, will benefit from the fact that Iranian allies will no longer dominate the northern Levant. And the Sunni Gulf Arabs may tremble less before the badly battered Shiite Persians; they will still want outsiders to protect them. Ironically, though, Israel may acutely feel a sense of déjà vu. Having done everyone’s heavy lifting against the Islamic Republic and allowed President Donald Trump to claim he’d restored a bit of America’s hard-power credibility, Jerusalem will still face a virulently antisemitic regime likely still seeking a nuclear weapon.

The Islamic Republic’s leadership is surely aware that Israel has nuclear weapons loaded on planes and perhaps on submarines, ready to strike its enemies. The doctrine of mutually assured destruction—or as Winston Churchill more colorfully put it, “safety will be the sturdy child of terror, and survival the twin brother of annihilation”—may be enough to hold vengeful Iranian Islamists with atomic arms at bay.

But Jerusalem can’t afford to think that way, of course. Israeli intelligence will need to be pitch perfect if it’s to preempt future Iranian threats since the entirety of the clerical regime’s nuclear weapons program will now be hidden. And the counterespionage services within the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, which oversees the regime’s atomic ambitions, and the Iranian intelligence ministry, are now cognizant of how massively Israel’s intelligence service, the Mossad, has penetrated the Iranian government. Iran’s internal security services had been cranking up their counterespionage capacity since Israel started assassinating nuclear scientists in 2010. They failed abysmally.

After Israel’s nationwide attack, these security services will become ferocious in their efforts to uncover spies. In this dragnet, a lot of innocents will get picked up. Many will get tortured to death. This inquisition alone could greatly delay the effort to reconstitute a nuclear weapons program that is “traitor-proof.”

The clerical regime may have invested so heavily in deeply buried facilities, at Fordow and Pickaxe Mountain at Natanz, because it wanted sites that might withstand bunker-buster bombs and Iranian agents of foreign intelligence services. If a spy ratted out a deeply buried facility, it would still remain challenging—at least for Israel—to obliterate with conventional weaponry. If a spy revealed a cascade of advanced centrifuges in a warehouse in Mashhad, then an Israeli missile could demolish it.

The deeply buried sites now will likely remain abandoned, regardless of whether they were completely destroyed, since reoccupying them would signal nefarious intent and might bring new Israeli and American raids. Digging new ones would take too long given the likelihood of exposure. Numerous easily concealed surface facilities may now be a better bet—so long as spies are neutralized.

Donald Trump may have bombed Fordow too late. The Iranians may have moved some of the uranium there and from other sites before either the Israelis and Americans attacked, potentially leaving the Revolutionary Guards with an accessible stockpile of highly enriched uranium. After all, the International Atomic Energy Agency, the United Nations’ nuclear watchdog, has never had live-time coverage of Iranian activities at known nuclear facilities. Satellite surveillance can leave doubts.

Whether the regime has been building a clandestine conversion facility for making enriched uranium into metal plates, which are essential for an A-bomb, is probably the biggest question facing Mossad. If their spies have penetrated the inner core of the weapons program, then they know that answer as well as whether the regime still has a stash of near-bomb-grade enriched uranium. All the dead nuclear scientists don’t necessarily add up to this kind of intelligence success. If the Iranians don’t have a backup to the Isfahan conversion facility, which has been destroyed, then they will probably have difficulty building another one quickly. Under the threat of Israeli attacks, the clerical regime would need to test Mossad continuously. Build a little at a new site, then see if something surfaces in the Western press or the site gets whacked.

The American and Israeli raids may have only scratched the regime’s capacity to build advanced centrifuges. We may not know yet how many nuclear scientists and engineers the Israelis killed, especially in the now all-critical lower ranks. They may have gotten the right ones in sufficient numbers to convulse the atomic program for a very long time. Thoughtful former Mossad officers think they may have done just that. But if the Iranian bench is deeper than the Israelis currently believe, then Tehran might be able to restart centrifuge construction quickly. Or, they may have never stopped.

Barack Obama’s nuclear deal, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, didn’t tell us anything about the centrifuge parts stockpiles the clerical regime had. And our knowledge of their dual-use imports became detailed usually only after U.S. intelligence discovered successful, illicit importation. After IAEA inspectors saw American-made capacitors in Iranian centrifuges, U.S. intelligence reverse-engineered how Tehran had obtained them. A lot of steps likely remain before the clerical regime can go nuclear—a new conversion facility to mold uranium metal plates and the completion of a nuclear trigger first and foremost. Building a nuclear warhead, if the regime hasn’t already done the required designs, might significantly delay the deployment of the ultimate weapon.

Regardless of how much time is required, Israel will have to assume that the clerical regime will now rush to make a weapon—unless its verified agents tell them differently. Given the dragnet the Iranians have surely already put in place, Israeli spies might get rolled up at any time or, worse, turned. The odds of Iranian deception—throwing out information through intercepted telephone calls, turned assets, or “dangles,” all suggesting that the regime isn’t proceeding toward a weapon—can’t be discounted. It’s a daunting task—the most consequential challenge that Mossad has ever confronted. Israeli intelligence may be up to it. Mossad’s accomplishments have so far been astonishing, and they certainly weren’t foreordained.

One of the hardest things imaginable is a bureaucracy reformed. “Secret” bureaucracies, like foreign intelligence services, are even more resistant to change, since it’s easier to hide routine incompetence and block nosy outsiders.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, it certainly appeared that Mossad wasn’t in great shape. Operations and intelligence collection in Lebanon were troubled: An assassination attempt in 1997 in Jordan on Khaled Mashal, who was then head of the Hamas political bureau, was badly bungled; and the successful but still embarrassing assassination of Mahmoud al-Mabhouh, a Hamas military commander, in Dubai in 2010 revealed an intelligence service that appeared to have forgotten the ABCs of running clandestine operations.

Even the prelude to the deadly October 7 Hamas breakout from Gaza suggested that Mossad, which doesn’t have primacy in collecting intelligence on Gaza and the West Bank, didn’t appear to have much on Hamas from its collection efforts in Egypt, Lebanon, and Iran. Hamas’ representatives had been meeting frequently with senior officials of the Lebanese Hizbollah and the Islamic Republic. And the Egyptian military, where love of lucre and anti-Zionist sentiments run deep, was surely well aware of all the matériels going through cross-border tunnels.

And yet Israel’s assassination operations against Iranian scientists revealed that things were getting better, particularly its remote-controlled machine-gun attack on the father of the regime’s A-bomb program, the nuclear physicist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, in 2020, and its theft of Iran’s nuclear archive from a warehouse in south Tehran in 2018. Jerusalem’s post-October 7 war against Hezbollah and, even more so, Jerusalem’s nationwide attack on the Islamic Republic’s nuclear sites and key personnel show that Mossad has developed breathtaking skill in both human-intelligence collection and covert action.

Credit must be given to Meir Dagan, the Mossad chief from 2002–2011, who kept a laser-like focus on Iran and alienated more than a few operatives with his bulldozer manners. To do what Mossad has done requires a political and professional leadership willing to absorb the pratfalls that inevitably come when espionage and covert action get serious. Dagan, his successors, and the Israeli elected officials overseeing intelligence work had the focus and intestinal fortitude to learn from mistakes.

Outsiders who’ve never been involved in recruiting and running agents in denied areas—countries where an intelligence service either doesn’t have an embassy or interest section to base itself or where the local service is so unrelenting in counterintelligence that diplomatically covered case officers have to take extraordinary precautions to engage in even the smallest operational activity—have no idea how demanding this work is. Mossad has probably been planning the operations that are now unfolding for years while the Islamic Republic’s security services were amping up their counterintelligence capacity.

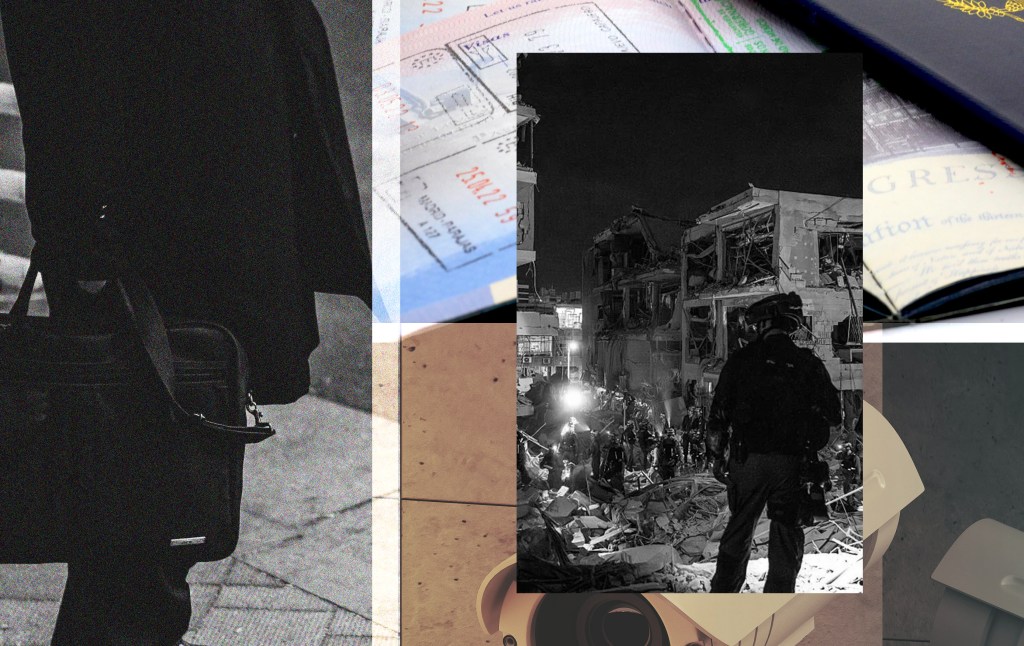

Most impressively, Mossad has repeatedly inserted its own officers into Iran. Because of Israel’s diverse ethnic makeup, Israeli operatives have many different ways to camouflage themselves. And Mossad has never been bashful about stealing other countries’ passports so they can be reworked into useful documents. Modern, security-laden passports have become a big problem for foreign intelligence services since they are often impossible to replicate: Theft and careful alteration are often the only avenue for certain operations.

No matter how the operations were executed, it was ballsy. There are always 1,001 ways things can go wrong. Little details—the small things about life in foreign lands—can undo an operative trying to appear either as a native or a foreigner of no interest. More so than foreign intelligence collection, covert action, where an operative or operatives in a team, often working with locally recruited assets, trying to accomplish a specific mission—for example, smuggling military drones into Iran—has a lot of moving parts. Little cock-ups are unavoidable. Significant mistakes could get everyone rolled up, tortured, and killed.

Israel and the Islamic Republic have for years been in a state of war. Contrary to what so many Democrats have reflexively spouted since the European Union began talks with Tehran in 2003 after its nuclear weapons program was revealed by an opposition group, diplomacy was never going to rein in, let alone stop, Islamist Iranian nuclear ambitions. JCPOA-enthusiasts inevitably skirted the touchy issue that we were making the clerical regime—and therefore its proxies targeting Israel—a lot richer. The agreement vouchsafed to the Iranian theocracy an international guarantee that within 10 years it could start building a massive uranium-enrichment infrastructure, which when developed would certainly be beyond the means for the IAEA to monitor. Extortion and bribery—the true heart of Obama’s accord—never had a chance unless the Islamic Republic could forsake its anti-Zionist ambitions. It couldn’t.

We certainly don’t know now whether Jerusalem’s decision, copied now by Trump, to try the military option will work either. If it is to work, the most important factor will be Mossad’s continuing capacity to do what the Soviets once did to the Anglo-American program to develop the A-bomb during World War II: have spies where it matters most.

It will be educational to learn how Israeli accomplishments play out within Langley. Too big, too confident, and historically uneasy with Mossad, the Central Intelligence Agency’s clandestine service may not even ask to see how the Israelis ran their operations. And the Israelis might decline to share. A retrenching superpower, uncertain of its place in the world, would do well, however, at least to try to develop some of the expertise that Israel has honed since Jerusalem decided it couldn’t avoid the dirty work required to best its enemies.