In an anti-institutional era, does any institution face more dangerous attacks than our Constitution’s judicial branch? Today, it faces outlandish political attacks from both the right and the left. President Donald Trump and other senior officials launch petulant insults against judges who rule against his administration’s policies. Democratic senators make reckless threats that Supreme Court justices should “pay the price” for their decisions and assert that the court itself should be “restructured,” because its decisions do not please them.

Throughout the Biden presidency, progressives called for the court to be packed or restructured; eventually, even President Joe Biden joined the chorus with a proposal to end judicial life tenure and regulate the justices themselves. Federal judges and justices now face such heated political attacks—even assassination threats—that the federal judiciary is considering creating an entirely new security force to better protect judges against this wave of threats.

It is an unsettling moment—but not an entirely unprecedented one. The judicial branch is supposed to be insulated from political pressure, but our history has witnessed many other moments when judges and courts have faced withering political attacks despite their constitutional protection, or perhaps even because of it. We saw this in FDR’s failed court-packing gambit; and in the Progressive movement’s flurry of proposals to subject the courts to direct democratic vetoes; and, more recently, in various Democratic and Republican proposals to strip the courts’ jurisdiction over cases involving racial segregation, abortion, and other matters.

Indeed, these debates go back to the very start. The first genuine presidential transition from one party to another—from John Adams’ Federalists to Thomas Jefferson’s Republicans—was preceded by a pitched fight over the courts. First, the Adams administration’s effort to restructure the federal courts and fill them with more Federalist judges. Then the Jefferson administration’s efforts to restructure the courts, eliminate the new judges, and even to impeach Federalist justices.

Even before that, one of the most important debates around the 1787 Constitutional Convention was on the power of a new federal judiciary. Anti-Federalists, especially the pseudonymous “Brutus,” raised compelling questions about the newly proposed federal judiciary, warning that federal judges would overrun the other parts of the federal government, and eventually the states, too. But Brutus’ attacks spurred the single greatest argument for an independent judiciary in a constitutional republic: Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist No. 78, on the need for judges who would wield “neither Force nor Will, but merely judgment.”

But Hamilton’s argument was far more nuanced than that. His sense of both the need for judicial power and also judicial self-restraint, and his sense of what makes a good republican judge, has never been timelier. Indeed, Hamilton’s argument is timeless precisely because it sensed the fundamental difficulty in protecting judges from democracy, but also protecting democracy from judges—akin to James Madison’s candid reflection, earlier in The Federalist Papers, on the profound constitutional difficulty “in combining the requisite stability and energy in government, with the inviolable attention due to liberty and to the republican form.”

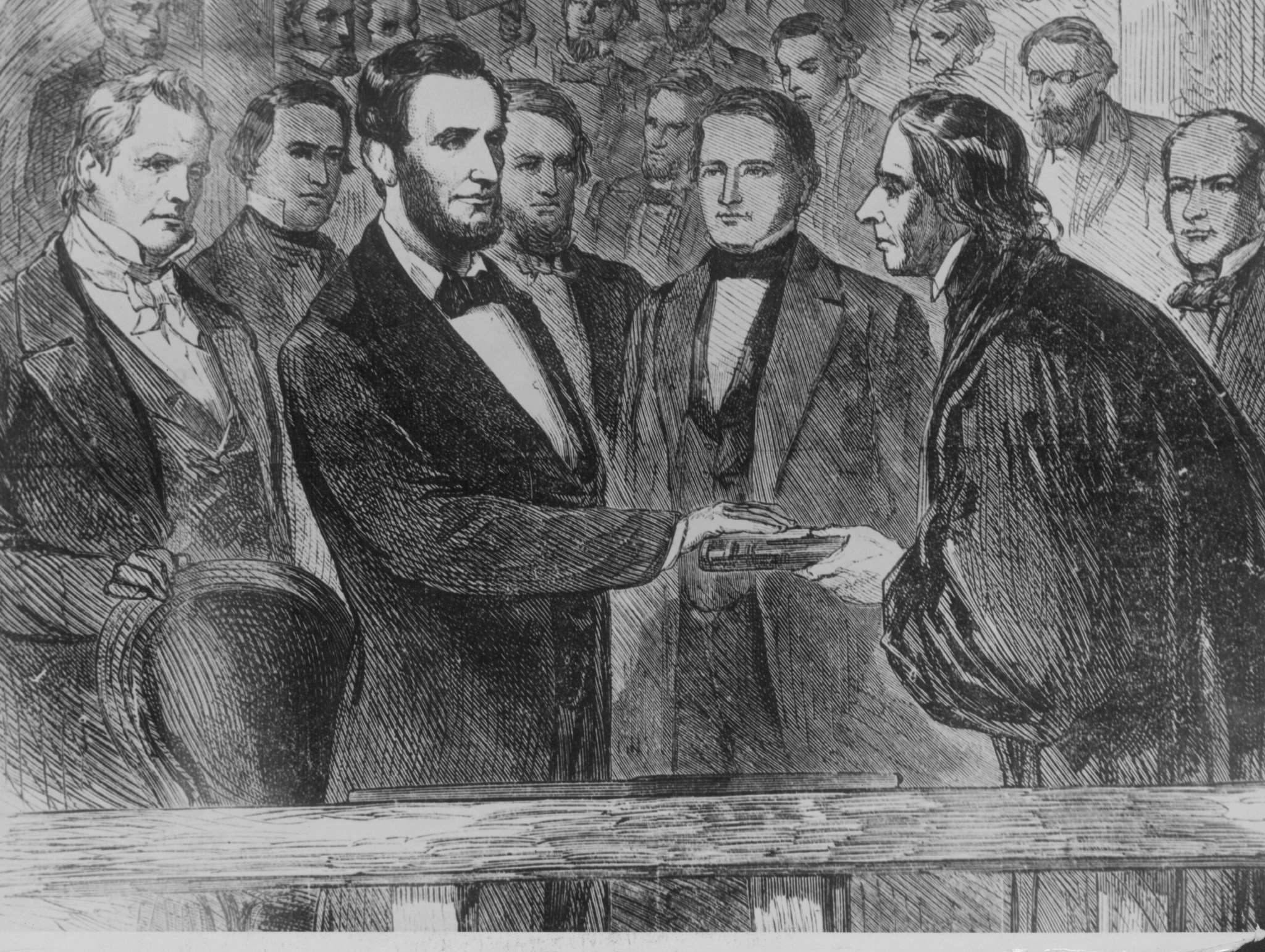

The same republican sensibility inspired Abraham Lincoln’s reflections on the Supreme Court, almost four years to the day after the court’s infamous and ruinous pro-slavery decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford.

“I do not forget the position assumed by some that constitutional questions are to be decided by the Supreme Court,” Lincoln said in his first inaugural address, “nor do I deny that such decisions must be binding in any case upon the parties to a suit as to the object of that suit, while they are also entitled to very high respect and consideration in all parallel cases by all other departments of the Government.”

But then he offered the single most vexing sentence in the history of American constitutional self-government:

At the same time, the candid citizen must confess that if the policy of the Government upon vital questions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, the instant they are made in ordinary litigation between parties in personal actions the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having to that extent practically resigned their Government into the hands of that eminent tribunal.

With Lincoln’s words in mind, and the nation’s 250th anniversary in view, how might the candid citizen think of courts and democracy today?

As it happens, the relationship between courts, the rule of law, and the rest of government was a central focus of the Declaration of Independence. After the Declaration’s famous opening passages, as the document turns to an indictment of King George III’s misdeeds, the list starts with his abuses of legislative powers but then moves to his abuse of the courts. “He has obstructed the administration of justice, by refusing his assent to laws for establishing judiciary powers,” the signatories announced. “He has made judges dependent on his will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.”

What caused these accusations? Pauline Maier explains them in her luminous book, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (1997). On King George’s prevention of laws establishing judiciary powers, Maier points to “an extended controversy in North Carolina,” where the king withheld his assent from a North Carolina law that would have empowered courts to liquidate nonresidents’ property for the nonpayment of debts; the Crown, Maier writes, considered this “contrary to the substance and spirit of English law.”

Perhaps that debate seems archaic today. The second one, however, is surely more salient in light of modern attacks on judicial life tenure. On King George’s attacks on judicial tenure and salaries, Maier points to a much broader colonial dispute. “Controversies over the independence of the colonial judiciary raged in Pennsylvania and New York” as early as the 1750s, and in 1761, the king “forbade the issuance of colonial judicial commissions for any term except ‘the pleasure of the crown.’” This was a stunning assault on the judicial life tenure that English judges had long retained, something that the king himself had hailed as “one of the best securities of the rights and liberties of his subjects.”

As Bernard Bailyn describes in The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (1967), “[a]ll of the colonies were affected,” and especially so in Massachusetts in the run-up to 1776, once the king declared that he would control judges’ salaries. “More and more,” Bailyn writes, “as the people contemplated the significance of crown salaries for a judiciary that served ‘at pleasure,’ was it clear that ‘the designs of administration [were] totally to subvert the constitution.’”

When the colonies won independence, they were able to restore judicial independence, to varying degrees, on a state-by-state basis. But federal law, such as it was in the initial confederacy, still was subject to the states’ own whims and preferences, because the Articles of Confederation provided for no federal judiciary except for courts for the trial of “piracies and felonies committed on the high seas.” In all other respects, an interstate rule of law would depend on each state giving “full faith and credit” to “the judicial proceedings of the courts and magistrates of every other State.”

But when the postwar government began to collapse, and a “more perfect Union” required a truly national government, with a Constitution and laws that would be “the supreme Law of the Land,” the delegates to the Constitutional Convention quickly grasped the necessary implication: The federal government would need a federal judiciary, at least in the form of one Supreme Court. The need for lower courts was somewhat less obvious—the Constitution authorized Congress to create “inferior courts,” but it didn’t command their creation. At the very least, the state courts’ misjudgments could be corrected by the Supreme Court.

And the Supreme Court, Hamilton argued in Federalist No. 78, would be a “bulwark” for liberty and the rule of law precisely because the Constitution guaranteed that justices “shall hold their offices during good Behaviour”—that is, the justices would serve for life, or at least until voluntary retirement subject only to constitutional impeachment. “In a monarchy,” Hamilton explained, life tenure “is an excellent barrier to the despotism of the prince; in a republic it is a no less excellent barrier to the encroachments and oppressions of the representative body,” and “it is the best expedient which can be devised in any government, to secure a steady, upright, and impartial administration of the laws.”

Hamilton could not have been more emphatic: Giving judges “permanent tenure,” he argued, is the best possible protection for “that independent spirit in the judges which must be essential to the faithful performance of so arduous a duty.” But, he continued, the Constitution also needed to guarantee judges’ life tenure in order to bring forth the very best kind of judge.

To “avoid an arbitrary discretion in the courts,” judges would need to be experts in the “voluminous code of laws” and the “records of those precedents” that would inevitably “swell to a considerable bulk over time.” Simply to learn the laws would “demand long and laborious study”—the kind of study that would normally be rewarded with a lucrative legal career.

But, he added, it was not enough for federal judges to be just well-educated. Federal judges, in a republican system, needed the right kind of character and virtues. “And making the proper deductions for the ordinary depravity of human nature, the number must be still smaller of those who unite the requisite integrity with the requisite knowledge.” Without the guarantee of life tenure, attracting great lawyers with great character would be practically hopeless, “throw[ing] the administration of justice into hands less able, and less well qualified, to conduct it with utility and dignity.”

As I noted earlier, Hamilton’s argument for judicial life tenure responded to the arguments of “Brutus” (possibly Hamilton’s fellow New Yorker, Melancton Smith), who warned that giving the Supreme Court not just life tenure but also the power to declare laws unconstitutional would inevitably tempt the court into autocracy. “There is no authority that can remove them, and they cannot be controuled by the laws of the legislature,” Brutus observed. “In short, they are independent of the people, of the legislature, and of every power under heaven. Men placed in this situation will generally soon feel themselves independent of heaven itself,” he warned.

“In a monarchy it is an excellent barrier to the despotism of the prince; in a republic it is a no less excellent barrier to the encroachments and oppressions of the representative body. And it is the best expedient which can be devised in any government, to secure a steady, upright, and impartial administration of the laws.”

Alexander Hamilton, on lifetime tenure for judges

Federalist 78

Brutus’ words could not be shrugged off lightly, in our own time no less than in Hamilton’s, thanks to Lord Acton’s warning that, “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power tends to corrupt absolutely.”

But Hamilton’s response in Federalist No. 78 reflected the very nature of the judicial office, as embodied by the traditions of the judiciary and the legal profession. Hamilton’s judges, again, would exemplify the best kind of legal wisdom and judicial character—and for this, the system would rely not just on the judges themselves, but also on the president who would nominate them and, crucially, the Senate that would confirm or reject the president’s nominations. (Writing on the Senate’s constitutional “advice and consent” responsibilities, Hamilton predicted that presidents facing a risk of Senate rejection “would be both ashamed and afraid to bring forward” nominees who were simply “personally allied to him, or of possessing the necessary insignificance and pliancy to render them the obsequious instruments of his pleasure.”)

Hamilton urged that federal judges would not be autocrats so long as they exercised their power of judicial review in a spirit of genuine self-restraint. On this point, there is Federalist No. 78’s most famous line, quoted above, on a judiciary that “may truly be said to have neither Force nor Will, but merely judgment.”

But more important are the essay’s less-famous lines about how judicial review would actually work in a constitutional republic. Yes, the courts would have a “duty … to declare all acts contrary to the manifest tenor of the Constitution void.” But, Hamilton spelled out, this means that courts must not declare a law unconstitutional unless there is no reasonable way to construe the law in a constitutional way.

“So far as they can, by any fair construction, be reconciled to each other, reason and law conspire to dictate that this should be done,” Hamilton explains. When there is an “irreconcilable variance” between the Constitution and a law, but only where that variance is irreconcilable, should the courts declare the law unconstitutional.

Today, it might be rather easy to chuckle at Hamilton’s vision for the federal judiciary. So much for that, no?

Not exactly. Even nearly a half-century after The Federalist, Alexis de Tocqueville’s own famous account of judges was still strikingly Hamiltonian. The American judge “is vested with an immense political power,” he observed, but a judge’s exercise of that power would be “enclosed” by the very nature of the judicial process as defined by the Constitution, procedural rules, and judicial traditions. First of all, American courts existed only to hear actual cases between actual parties, not to simply decide constitutional questions at will. Second, when actual cases came to the courts, the judge would decide the “particular question” at issue, not simply announce general abstract theories of law. And finally, the American judicial power “is able to act only when it is appealed to, or, following the legal expression, when it is seised [of a matter].”

And for Tocqueville, the “essential” point was the last one: American judges were safe for democracy because their office made them purely reactive, not assertive. Cases found judges, not vice versa. The American judge never “entered onto the political stage with a bang,” Tocqueville writes (with Harvey Mansfield’s and Delba Winthrop’s beautiful translation), “[b]ut the American judge is led despite himself onto the terrain of politics. He judges the law only because he has to judge a case, and he cannot prevent himself from judging a case.”

The alternative, Tocqueville saw, would be ruinous. “The judicial power would in a way do violence to this passive nature if it took the initiative by itself and established itself as censor of the laws.”

Perhaps that is the thing that needs the most attention from us today—not simply the substance of the court’s work, but the process, and especially the pace.

We are long accustomed to arguing over the substance of justices’ constitutional decisions. Normally—and understandably—the general public tends to read Supreme Court news headlines through a political lens: Did the Supreme Court uphold a policy that I like? Did it strike down a policy that I dislike?

Lawyers, legal journalists, law professors, and other specialists approach the substantive question with a little more principle, or at least one would hope so. At their best, those who know the court rightly focus on the court’s substantive methodology. Did the justices faithfully read the Constitution or law in terms of its originally understood meaning?, today’s originalists ask. Did the justices fairly apply the Constitution in light of modern understandings of the Constitution’s word and spirit?, others ask. Did the justices uphold or overturn a precedent for the right reasons?, practically everyone asks, albeit with their own underlying premises about what the right and wrong reasons might be.

We ask these questions because the judges’ substantive methodologies are, at root, the most important thing, for all the reasons that Hamilton and other great statesmen of the Founding understood. But we also ask these questions because they are the most familiar. Originalists and non-originalists disagree profoundly on how to read the Constitution, but today we all come to these substantive debates with familiar, well-developed vocabularies for each side of the debate.

The procedural debates are much more difficult, for at least two reasons. First, they are simply newer. We have debated the substance of modern originalism and anti-originalism for practically half a century, but debates about the pace of judicial intervention are much newer. Only very recently have debates about the Supreme Court’s so-called “shadow docket”—its docket for emergency procedural motions, on whether to freeze an administration’s action or a lower court’s order while the litigation is proceeding, or to allow it for the time being—come to overshadow debates about the court’s final decisions in fully litigated cases.

And, for that matter, only in the last couple of decades has constitutional litigation come to be defined by district courts quickly granting “nationwide injunctions,” largely in lawsuits that state attorneys general or activists bring in a very small number of courts where the judges’ methodologies already line up well with the plaintiffs’ claims.

But second, it is harder for originalists and non-originalists alike to debate the pace of judicial review. We have methodologies for how to interpret a law, and we have vocabularies for debating those methods, but we have neither methods nor phrases for describing when is the right time for the court to take a case or grant an emergency stay, or how soon to schedule an oral argument or decide the case. The pace of the courts’ proceedings surely affects both the substance of a judge’s work and the public’s perception of that work. Yet we have not learned how to evaluate the process and the pace of good constitutional judgment.

It is surely no coincidence that our era’s profound change in constitutional litigation coincides with an equally profound change in modern president-centric policymaking (as I wrote recently in The Dispatch). But it is hard enough to wrap our arms around the full implications of the modern administrative state. It is even harder to fully grasp the changes we have seen recently in the federal judiciary.

Still, it is increasingly clear that the sheer amount of discretion involved in the justices’ power to choose their cases (the power to grant or deny “certiorari,” which Congress gave to the court in 1925), and the similarly boundless discretion that justices wield in deciding whether to stay an administration action or lower-court order at the very earliest stages of a case, are increasingly difficult to square with the original notion of the judiciary. That is, it is hard to see the Supreme Court’s procedural discretion in a way that is consistent with Hamilton’s judiciary that lacked a “will” of its own, or with Tocqueville’s judge, who wields the power to judge a case only because “he cannot prevent himself from judging a case.”

This is, to be sure, not the current justices’ fault. A century ago, Congress gave the Supreme Court discretion to choose its cases. Congress delegated that discretion, to the then-justices’ great relief, in order to cope with the sheer volume of litigation reaching the court. Today’s court simply could not do justice to every possible appeal from the circuit courts and state Supreme Courts.

“We have debated the substance of modern originalism and anti-originalism for practically half a century, but debates about the pace of judicial intervention are much newer.”

Similarly, the justices’ power to issue unexplained emergency orders—again, the ominous-sounding “shadow docket”—is a well-precedented judicial tool that is now being sought by litigants with unprecedented frequency in a staggeringly unprecedented policymaking era. The power and velocity of modern executive power has no real precedent, nor does the sweep and speed of modern district courts’ nationwide injunctions.

For both its selection of cases and its issuance of emergency orders, the Supreme Court has long tried to impose standards on itself: in choosing cases, the court explicitly prefers legal questions that have divided lower courts, or that involve a particularly “important question of federal law”; in granting emergency stays, the justices have long said that there must be a “reasonable probability” that the Supreme Court eventually will hear the case in full, a “fair prospect” that the court will reverse the lower court, and “irreparable harm” would occur in the absence of the stay. But these standards, too, are acts of the court’s own will and discretion—laudable ones, but still ones of the justices’ own creation. It is long past time for Congress to amend the laws that empower the Supreme Court, to impose clearer standards for which cases the justices must hear, and what kind of remedies are available in a given case.

But, quite frankly, the genuine source of the problem probably reaches far deeper into America itself. The same culture that powers the administrative state also powers the pace of modern litigation. That is, the same culture that drives politically engaged Americans to demand immediate policies from their government also demands immediate resolution from a judge, and then from the Supreme Court. It is surely the instinct that causes us to bristle when our Netflix buffers, or to grumble when our GrubHub delivery is 10 minutes late.

Are we capable anymore of tolerating a constitutional judiciary that works with the judicial self-restraint and deliberation that, as Hamilton and Tocqueville and others warned, our constitutional system needs? Let’s hope so, because it is indeed our only hope. The Constitution’s institutions are our “auxiliary precautions” for liberty and the public interest, but our primary precaution is “the people themselves,” the founding generation that ratified the Constitution at the start, or the later generations who perpetuated or even improved it at our nation’s turning points.

Which brings us back to Lincoln. His first inaugural warned us not to put too much weight on the courts, but also not to put too little weight on them, either. His real warning, then, is the importance of knowing how hard it is to strike that balance.