“Yet men go out and gaze in astonishment at high mountains, the huge waves of the sea, the broad reaches of rivers, the ocean that encircles the world, or the stars in their course. But they pay no attention to themselves.” —Saint Augustine, Confessions

To know a little about Saint Augustine (354—430) is a dangerous thing. To know a little about anyone or anything of importance is also a dangerous thing, especially today when a news blip (perhaps transplanted by some bot farm) that skates across our screens is taken for truth and repeated ad nauseam; when the players are playing the played; when the plague of FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) infects the unquiet mind with rabid restlessness and unquenchable want; when rage is running rampant and volatility in all its forms and its attendant psychosis are enflaming our lives and incinerating the social contract. In today’s world, there is no dousing this conflagration with the balm of truth that will set us all free; truth only fans the flames.

You need not be a Christian or even believe in God—if that word for a transcendent creator is somehow too odious, but that’s the word Augustine used and I will be using here—to want to understand what Augustine had tried to do with his momentous life. And the depth of our understanding depends on our willingness to see him first and foremost—as he himself would want us to see him—as just another struggling soul who messed up some things in his life, who tried to change his ways, and who tried to show others how they, too, could make amends and cure whatever ills they had allowed to take over their lives. The story that Augustine reveals to us in his Confessions is nothing if not that.

We can see ourselves in him—in his Confessions—if we open our heart and mind to our own foibles and faults and failures, to our desire for forgiveness of self and others, and to our longing to be swept away by the gifts of beauty. It’s true that this book is not the easiest to read. But even if this story of Augustine’s evolution is situated in a particular time and place and clothed in the language of scripture and ancient philosophy and even metaphysics, what Augustine achieved and passed on to us through his Confessions has universal value. His story is our story. It is the story of Everyman.

“Although his experiences are profoundly personal,” writes Paul Henry in his book, The Path to Transcendence: From Philosophy to Mysticism in Saint Augustine, “they are nevertheless so rich and so full that souls of every age and every land have been able to recognize in his descriptions their own finest and most beautiful experiences.”

***

I first read Saint Augustine’s Confessions in the spring of 1995. I had enrolled in a course on the life and times of Saint Augustine at a seminary in New York City. I audited the class, taking Amtrak once a week for the two-hour trip from my home in the Hudson Valley, to find out if I wanted to apply to the seminary’s Master of Divinity degree program.

Going into the course, I knew very little about the man and his times. What I knew about Augustine then was perhaps what most people know because so much has been made of it—that he struggled with sexual temptation and even once in his younger days admitted that he prayed to God, “Give me chastity and continence, but not yet.” He did this because—and here, as in so many other instances, context is everything—he goes on to write in his Confessions, “For I was afraid that you would answer my prayer at once and cure me too soon of the disease of lust, which I wanted satisfied, not quelled.” We cannot know exactly what was going through his teeming mind when he wrote this. Some say he was poking fun at his youthful self. And who could blame him? By all accounts, it appears that his early life was so rife of adolescent shenanigans that he, like anyone of us looking back on our youth, was appalled at what he’d gotten away with and somehow lived to tell the tale.

And yet, he also had a serious, self-possessed side to him. I would learn that Augustine was a tireless seeker of knowledge and experience, and in his life, each influenced the other. The knowledge he sought directed the course of the experiences to which he opened himself. At the same time, the experiences expanded the breadth and depth of this knowledge. Ultimately, what he wanted most to know and to experience was genuine happiness.

As a teenager, Augustine was deeply influence by the writings of Cicero. Henry Chadwick in his book, Augustine, writes:

“Cicero’s ideal was personal self-sufficiency and an awareness that happiness, which everyone seeks, is not found in a self-indulgent life of pleasure, which merely destroys both self-respect and true friendships. Contemplating the paradox that everyone sets out to be happy and the majority are thoroughly wretched, Cicero concluded with pregnant suggestion that man’s misery may be a kind of judgement [sic] of providence, and our life now may even be an atonement of sins in a prior incarnation.”

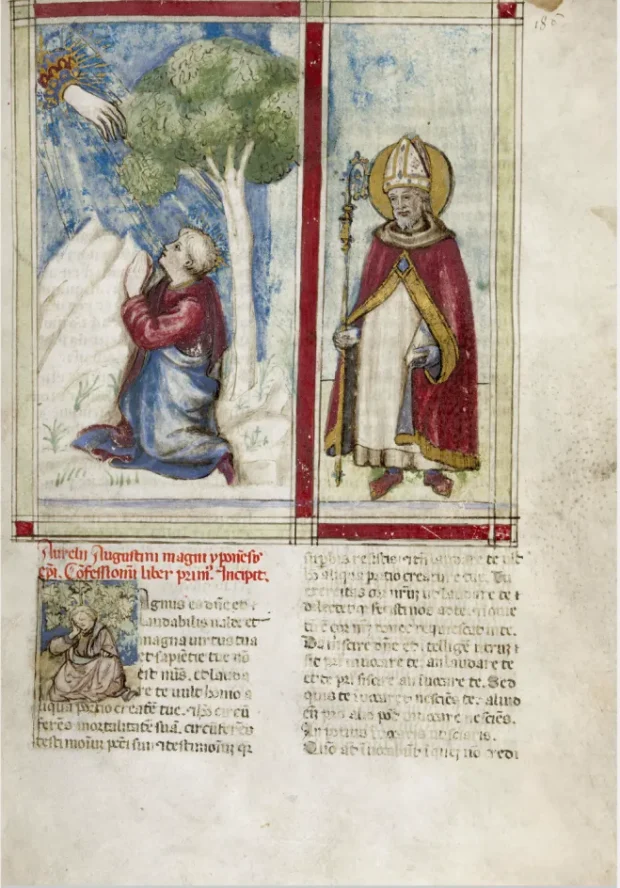

An illuminated version of Saint Augustine’s Confessions. Unknown Printer, Florence 1456-1480. (Source: Villanova University)

In his youth and early adulthood, Augustine, by his own admission, dissipated himself searching for happiness in the external and temporal world despite what he’d read of Cicero, particularly his Hortensius, as well as of Plato and the Neoplatonist, Plotinus, who focused on the interiority of life and liberation from the distractions of the external world, including—or especially—sexual relations. As he approached middle age, however, he realized, that his own happiness and the happiness of all of us is to be found in the spiritual life or, more to the point, the search for God.

The pendulum of Augustine’s life had apparently swung from one extreme to the other as if he had been driven by some psychological compensatory effort to find a middle ground. Perhaps because he was so repelled by his behavior in his early life and so startled that he’d been looking for happiness in all the wrong places, he never really found that middle ground. The remainder of his life would be spent in a restless search for that true rest in God.

His was a restless search because God, though eternal and changeless and always with us, was, for Augustine, elusive. Around the time he converted to the Catholic faith when he was in his 30s—partly at behest of his devout Catholic mother, Monica—Augustine had come to the conclusion that our knowledge of God, in this life, would remain incomplete. But that never stopped him from searching. And his search was a deeply personal toil. Certainly, there were plenty of intellectual guideposts and guides along the way. But the ultimate source of his knowledge came from his own experience. It was if he had to first stumble through the dark to see the light.

“In Augustine there were two natures, one passionate and sensuous, the other eagerly high-minded and truth seeking,” writes Williston Walker in his book, A History of the Christian Church. The Confessions is very much a story of his struggle with these two natures. Yet, this is not all that he revealed in his Confessions. He also grappled with having to abandon his secluded, private life of close friends as he increasingly became a popular public figure.

He came to write his Confessions in his 40s, a time in his life when he had achieved a modicum of admiration, notoriety, and respect; the book would become a best-seller. He began the book around 397, a few years after he had been appointed Bishop of Hippo (now Annaba in Algeria). And yet he wrote the book not to boast; rather he wrote it to cut himself down to size, to “make out a case against himself before an audience which was predisposed to believe him a saintly man,” writes R.S. Pine-Coffin in his introduction to his translation of the Confessions that I used for this essay.

Indeed, Augustine wanted to show the world that he was not always the flawless person many of his parishioners perhaps imagined him to be. He did not want to be put on a pedestal. All his life he longed to be close to people; he adored his friends and was rarely alone. Here, at the peak of his career as a Roman cleric, he suddenly felt more unknown and isolated than ever. And he didn’t like it. Peter Brown writes in his exceptional book, Augustine of Hippo: A Biography:

“As Augustine faced his congregation, perched up on his cathedra, he will realize how little he would ever penetrate to the inner world of the rows of faces…. And Augustine’s insistence on revealing his most intimate tensions in the Confessions, is in part a reaction to his own isolation: it is, also, a deliberate answer to a deep-seated tendency of African Christians to idealize their bishops. In a world of long-established clerical stereotypes, it is a manifesto for the unexpected, hidden qualities of the inner world—the concentia.”

He also wrote the book to make himself better known among his ecclesiastical contemporaries near and far. Brown writes:

“Augustine will also have to resign himself increasingly to a purely African circle of episcopal colleagues. The other men to whose friendship he felt entitled—Paulinus at Nola, Jerome in Bethlehem—remained far away. He would have to content himself with ‘knowing their soul in their books’. This phrase might be a polite cliché for some Later Roman correspondents; but as we have seen, it forced Augustine to commit himself to writing the Confessions. For this book, at least, could carry his soul across the sea to the friends whose absence tantalized him. It is the touching reaction of a man drifting against his will into a world of impersonal relationships.”

Augustine intrigued me. I saw something of myself in him. What most intrigued me was not his struggles with his concupiscence or his fame but rather his profound thinking and beautiful writing. And his desire to be known—to reveal his depths—in his writing. That is to say, I was far less interested in his way with women and his public life than I was with his way with words and how he used them to explore and express himself, to make himself better known to others, to connect with others. It was one of the motivations that led me early in life into writing, and partly what has inspired me to write this Underlined Sentences column.

Educated as a rhetorician, Augustine became a teacher who would later leave teaching to become a priest in the Catholic church. Above all, his Confessions is a kind of conversation with God. In this conversation, Augustine speaks and asks questions and God answers in passages from the scriptures. What’s at stake here is that Augustine so much wants to know who he is and who God is. He also wants to know what genuine happiness is and how to find it. Throughout much of the Confessions, he is often on the cusp of finding out. It not only drove his life. This search is what drives the story; it’s the plot line.

This all came clear to me one day during that class I took. As the professor, an erudite Oxford educated theologian and priest, spoke about Augustine’s search for God and for himself in the Confessions, he said something so startling—and seemingly off the cuff—that it has stayed with me all these years later. He said, “For Saint Augustine, only God knows us better than we know ourselves. So, the search for self and the search for God are one and the same damned thing.”

These words cracked something open in me. They made me think I was in the right place at the right time in my life. They inspired me to apply to the seminary, which I did and into which I was accepted in the fall of 1995. All of this speaks volumes about how a good teacher can change the direction of a student’s life. I could belittle my role in this by saying that all I did was show up. But a writer friend of mine once said that’s what a meaningful and creative life is all about: just showing up. And it did take a considerable amount of time outside of my full-time job to do this. I like to think there was a confluence of energies that offer some validity to the idea of how when the student is ready, the teacher appears. It’s a form of divine intervention. I think it’s what happened to Augustine and it had also happened to me when we were both about the same age and at a kind of crossroads in our lives.

Perhaps it was the same confluence of energies that led me to a little-known book by Hannah Arendt, best known for her masterpiece, The Origins of Totalitarianism. This other book, Love and Saint Augustine, was Arendt’s 1929 doctoral thesis. (An English translation, including revisions by Arendt, was not published until 1996.) I’d only learned about this book while preparing this essay, and in reading it I found something that was similar to what that professor said some 30 years ago. In her book, Arendt writes: “Self-discovery and discovery of God coincide, because by withdrawing into myself I have ceased to belong to the world. This is the reason that God then comes to my help. In a way I already belong to God.”