Yes, BLS Reports Have Some Problems

Every month, the BLS publishes figures from two different government surveys of the U.S. labor market: the “household survey” (which gives us the unemployment rate, among other things) and the “establishment” or “payroll” survey (which gives us the “nonfarm” jobs numbers). The latter is what caused Friday’s chaos, and—as Bloomberg’s Justin Fox detailed early last week—it’s generated from the payroll figures of more than 120,000 U.S. employers delivered to BLS electronically or over the phone. The payroll report differs from the household survey in several ways, but the most important distinction for today is, as Fox explains, that the former is revised three different times over the course of a year:

The first two revisions come as information trickles in from late-reporting employers — only about two-thirds submit their numbers in time to be included in that month’s jobs report. Then comes an annual “benchmark revision,” based mainly on state unemployment insurance records, which leads to changes every February in the previous 21 months of not seasonally adjusted numbers and the previous five years of seasonal adjustments. Other corrections and historical reconstructions often follow.

These revisions are intended to improve the payroll numbers’ accuracy and long-term value to economists, policymakers, investors, and more. However, Fox presciently adds, “[T]he many revisions paradoxically lead to much more public skepticism about the accuracy of these statistics than the less accurate but never-revised numbers derived from the household survey.”

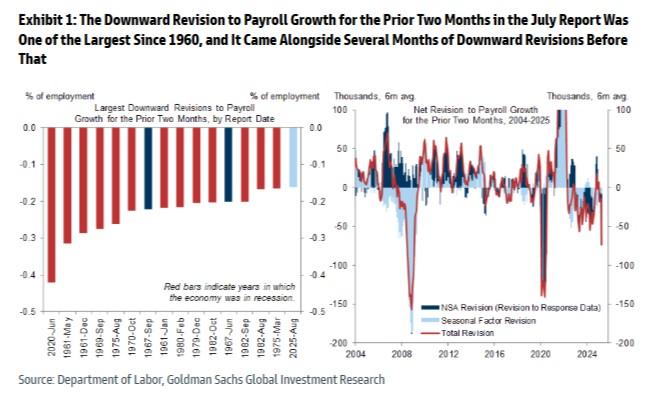

Indeed, Trump’s defenders have latched on to relatively recent and significant revisions to the payroll figures as grounds to fire the BLS commissioner, and in one very narrow sense they have a point. As economists at Goldman Sachs noted over the weekend, for example, the combined downward revision to the May and June payroll figures was, at 258,000, the largest two-month, non-recession revision since 1968:

Annual revisions to the payroll data have also been quite large in recent years, with last September’s preliminary benchmark trimming more than 800,000 jobs from the annual U.S. job creation total.

But It’s Not a Political Conspiracy

These issues, however, aren’t the big political conspiracy that Trump and others have claimed. For starters, several aspects of the payroll survey make a fast and super-accurate report effectively impossible. Fox notes, for example, that properly accounting for new business formations and closures in a massive and dynamic U.S. economy has been a longstanding challenge that the BLS has continuously worked to address. Its current model nevertheless struggles during recessions and, given recent non-recession revisions, may need more updating in the post-pandemic U.S. economy. National Review’s Dominic Pino adds several more practical hurdles for the tens of thousands of businesses reporting their numbers to the government, such as properly accounting for contractors or new hires—an especially difficult task “for large businesses, where countless managers have hiring and firing authority throughout the company.”

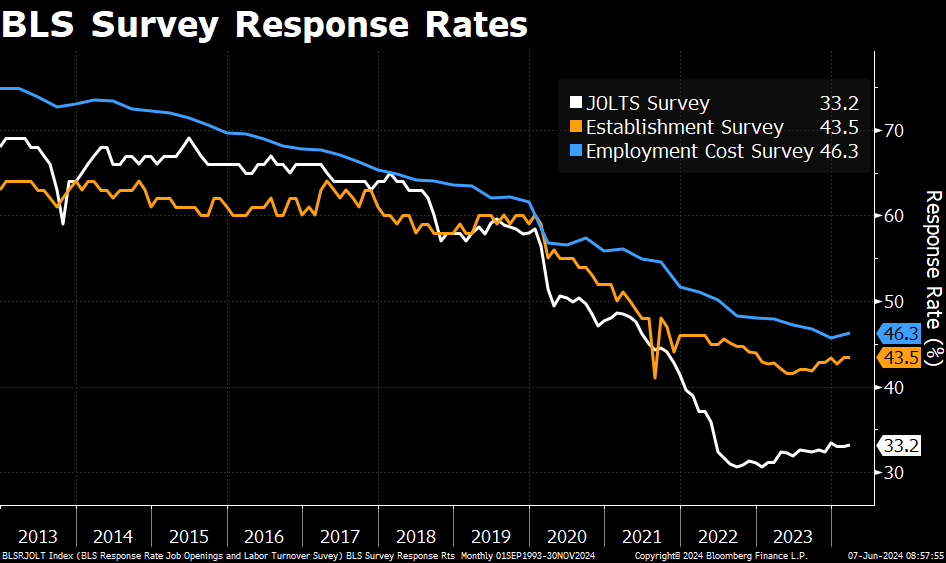

The other big challenge to the payroll surveys is more recent: As several observers have noted, the response rate of surveyed companies collapsed at the beginning of the pandemic and never recovered:

Fewer reporters mean less-accurate reports. Employers and the government get better data over time, so subsequent revisions to the payroll reports are more accurate. But waiting a year for an initial set of U.S. employment figures would raise other, obvious problems, so we get an initial report quickly and then we get more accurate revisions in the following months, with changes and methodologies all transparently explained along the way.

BLS and labor wonks are aware of the challenges that the current system faces, especially the declining response rate. As a result, many folks have proposed possible changes to the system, such as by continuing to report the initial data but shifting the report’s attention to a three-month change instead of one month. None of those solutions, however, involves firing the BLS commissioner the same day you get a bad jobs report.

Trump’s Response Won’t Solve Anything

That’s because firing McEntarfer won’t address any of the White House’s concerns. For starters, as former BLS Commissioner (and Trump appointee) Bill Beach just explained to Politico, the commissioner just reports the survey results and couldn’t “rig” the data if she tried:

These numbers are constructed by hundreds of people. They’re finalized by about 40 people. These 40 people are very professional people who have served under Republicans and Democrats. And the commissioner does not see these numbers until the Wednesday prior to the release on Friday. By that time, the numbers are completely set into the IT system. They have been programmed. They are simply reported to the commissioner, so the commissioner can on Thursday brief the president’s economic team. The commissioner doesn’t have any hand or any influence or any way of even knowing the data until they’re completely done. That’s true of the unemployment rate. That’s true of the jobs numbers. As a consequence, there’s very little chance that there could be any influence from the commissioner.

Given this rather obvious hole in the president’s case, the White House has pivoted to claiming that the commissioner’s ouster was about the payroll report’s large revisions and aforementioned methodological problems, but this is also nonsense for multiple reasons. Most obviously, Trump expressly and repeatedly (even yesterday) said he fired the BLS commissioner because she “rigged” the jobs data for political reasons—a claim that’s, again, ridiculous on its face and one belied by the rather obvious fact that he was cheering the data a month ago. In fact, mere hours before Trump fired the commissioner, his vice president was crowing about this month’s BLS report showing gains for native-born workers (a nonsense claim itself, but that’s an issue for another time).

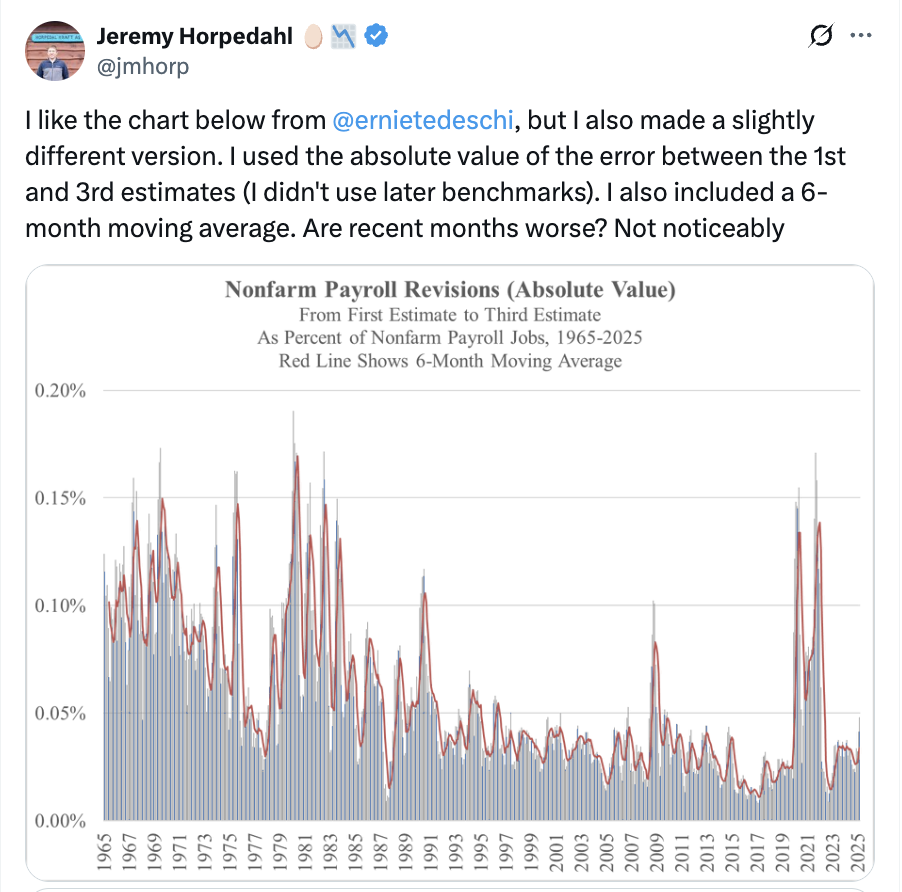

Second, large revisions to the payroll figures and the various technical issues underlying them started long before both Trump and McEntarfer took office and have cut both ways in recent years, with both downward and upward revisions and no clear political tilt thereto. Even more importantly, there’s no sign of a big deterioration in the payroll reports’ accuracy, and the White House has yet to show any evidence of that problem (or of political interference). In fact, despite the challenges the BLS faces and some big recent misses, the bureau’s first estimates have actually been getting more accurate—meaning they’re deviating less from the final figures – over the long term:

Finally, as my British colleague Ryan Bourne reminded me over the weekend, survey response issues and report variability aren’t unique to the United States, as the United Kingdom is having similar problems.

This doesn’t mean the initial payroll reports can’t be improved or that certain things like response rates aren’t a concern (see here for more). And a new BLS commissioner might eventually be able to improve the data and methodologies that have been generating recent and large revisions to the payroll report. But none of that would justify or necessitate the instant firing of the current BLS commissioner following one bad report. It won’t solve a thing.

But It Does Risk Bigger Problems

If Trump’s move were only about inefficacy, we could dismiss it with a few snarky tweets, but the sad reality is that it raises a host of new and serious concerns. First and most obviously, the firing will inevitably taint public perception of the accuracy—and thus value—of all U.S. government data, not simply the jobs report. Even if Trump replaces the BLS commissioner with the best wonk on the planet, millions of people—partisans, yes, but surely others too—won’t believe the jobs numbers being reported. And they’ll justifiably start asking what other data may also have been politicized—a concern the White House didn’t exactly tamp down when National Economic Council Chair Kevin Hassett suggested the White House would review more than just the jobs reporting or when the administration scrambled to issue a “report” on supposed BLS survey biases that … showed no such thing.

Second and relatedly, a lack of confidence in federal economic data can have real market repercussions, even if the figures remain accurate. As numerous folks have written since Friday, the BLS figures, even with their flaws, are well-respected and relied upon by businesses, investors, U.S. policymakers, central banks, and other governments. Other government data, such as those published by the U.S. Energy Information Administration, are similarly regarded—if not more so. And, while private alternative data like the monthly ADP payroll figures do exist, they’re not without their own serious limitations. Indeed, that financial markets around the world react swiftly—and often significantly—to the monthly jobs reports and other economic releases is a clear indication of their value and of the current lack of sufficient private alternatives.

Widespread doubt about government figures would weigh on economic efficiency and resource allocation by distorting market actors’ decisions about hiring, investment, debt-issuance, and other business moves and by increasing transaction costs (e.g., forcing people to find or produce alternative data). This skepticism can also inhibit public oversight and analysis—either critical or supportive—of the government’s policies and fiscal situation and of the politicians implementing these things. Maybe in the long run better private alternatives would emerge in a world without government stats, but that libertarian paradise (ha!) would take months if not years to materialize—and even longer for people to trust the private data like they do (or did?) the BLS and other government sources.

In the meantime, however, the U.S. economy will be worse off.

Third, there’s the clear risk that government data actually do become less accurate or transparent in the years ahead. Beyond the concern that the Trump administration may be willing to pressure government statisticians into fudging politically important numbers (e.g. on manufacturing output or southern border crossings), there’s also the less obvious risk that federal bureaucrats simply adopt different methodologies because they feel implicitly pressured to report good figures or risk being fired. As anyone in the economics biz can tell you, getting to a final, published number typically requires several small methodological decisions along the way—ones that don’t necessarily have a “clearly right” answer but instead require professional judgement about what will produce the most accurate result at the end. Trump’s firing of a public employee for reporting a politically inconvenient number might thus cause others to preemptively ensure their jobs aren’t at risk by making judgment calls that collectively ensure more positive results.

Or it could lead to simply offering less data. Indeed, the ostensible grounds for firing the BLS commissioner stem from the agency’s issuance of timely reports on important economic indicators and its transparent revisions to those figures as better, more accurate data arrive. But if the revisions get you into political trouble—few politicians and hacks complain about the one-off monthly household survey—maybe the easy answer for a risk-averse bureaucrat is simply to stop making the revisions.

Less and worse government data would surely amplify the costs that mere doubts about their reliability could inflict on the U.S. economy. Research shows, for example, that clearer and better economic reporting tends to correspond with improved national economic performance across a range of important metrics (productivity, output, incomes, etc.). As we discussed in 2022, moreover, one of the reasons that authoritarian regimes consistently underperform economically is that they generate unreliable information that might make the state look good but doesn’t reflect reality. In these places, bad data can come from the bottom up (local governments, bureaucrats, and businesses providing bogus stats to keep The Boss happy) and from the top down (the central government cooking the books to make The Boss look good). And, while bogus numbers might bolster perceptions of the regime in the short term, autocratic economies can unravel over longer periods because the informational vacuum undermines “government and private sector decision-making on economic, military, public health, and other crucial policy matters.”

This problem is at its worst in authoritarian regimes where countervailing private information is also suppressed, and it’s something now weighing on the still-struggling Chinese economy under Xi, where data and economists keep mysteriously disappearing. But the headwinds aren’t unique to autocracies. The study I discussed back in 2022, for example, found that many “partly free” countries also suffered from informational problems that undermine economic performance. And, as the New York Times’ Ben Casselman just documented, some of the worst data-manipulators in recent history were the governments of ostensible democracies Argentina and Greece. That manipulation unsurprisingly coincided with intense economic suffering—with the former both fueling and fueled by the latter. Private alternative data did eventually emerge in those places to shine some light on fiscal and other matters, but not before the countries’ economic fate was sealed. And it’s taken both nations years—and in Argentina’s case a chainsaw-wielding libertarian—to recover in terms of both institutional credibility and economic performance.

Maybe Trump’s rash move on Friday won’t lead to these and other problems, but it’s undoubtedly a big and troubling step in that direction.

Summing It All Up

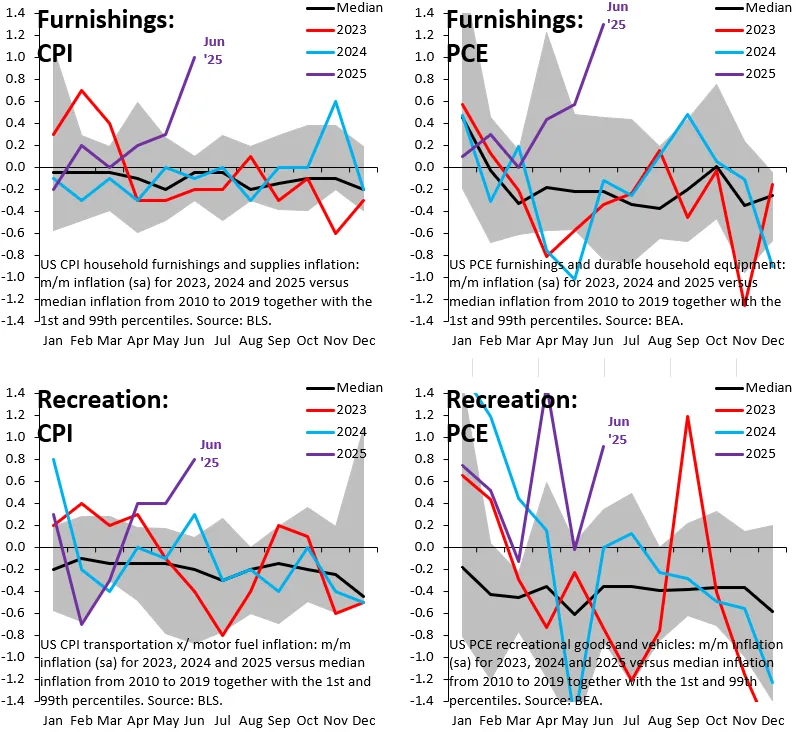

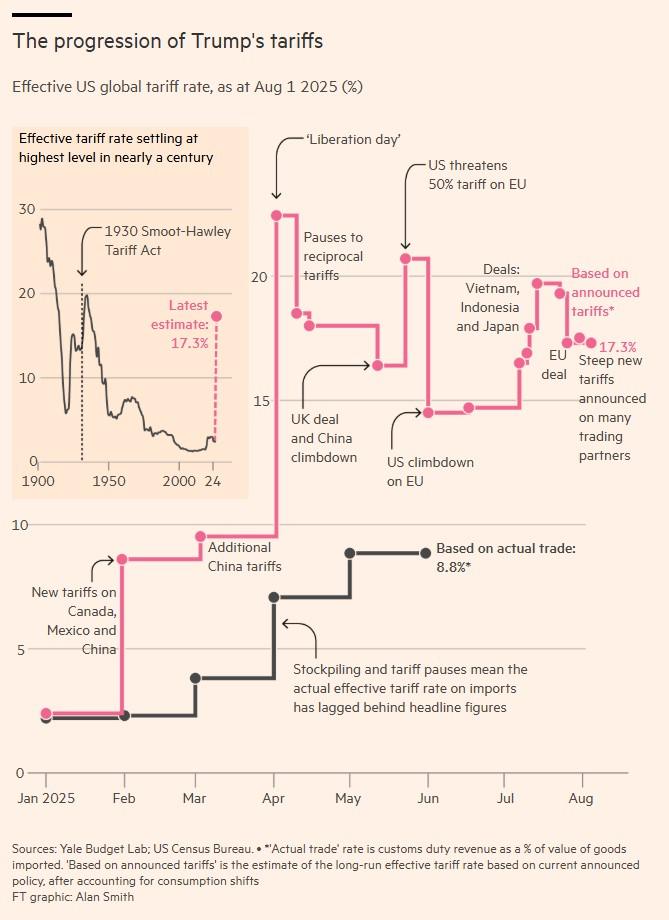

Last week’s soft jobs numbers weren’t a political conspiracy to undermine Donald J. Trump and weren’t strong evidence of persistent and unaddressed methodological problems at BLS. They were, instead, the predictable result of onerous and uncertain U.S. trade and immigration policies smacking into a U.S. economy that was already slowing before the new Trump administration took office. Indeed, as American Action Forum’s Douglas Holtz-Eakin documented earlier this week, the U.S. economy hasn’t consistently generated new jobs outside government or health care/education for a while now. Last week’s jobs report continued that trend and revealed additional labor market weakness. And it followed a sour July 30 report on second-quarter economic growth (excluding volatile trade and inventory distortions caused by Trump’s tariff actions), the next day’s “personal consumption expenditures” (PCE) report showing significantly higher goods prices and slower consumer spending, and yet another survey revealing sluggish U.S. manufacturing performance. (We’ve actually lost 37,000 manufacturing jobs since April, by the way.)

This doesn’t mean the U.S. economy is imploding, but it’s surely showing signs of strain—some of them self-inflicted. In a sane world, Megan McArdle rightly observes, the president would heed the warning signs and change course on policy. Or, at the very least, he’d use the soft economic data to bolster his case against the Federal Reserve or, as some pundits (and his own VP) did, cherry-pick the reports to show “clear evidence” that Trumponomics is working. Instead, Trump summoned his inner autocrat, declared the economic message “RIGGED,” and proceeded to shoot the messenger. In the process, he likely made things worse for himself and the economy, while likely boosting the relative fortunes of censorious tinpot autocrats around the world. It’s all, quite frankly, embarrassing—precisely the opposite of what a confident leader of the world’s greatest economy would do and just the type of stuff we mock and expect from China, Iran, North Korea, and other authoritarian regimes weighed down by their own statist policy mistakes.

We’re America, dammit. We should resume acting like it.

Chart(s) of the Week