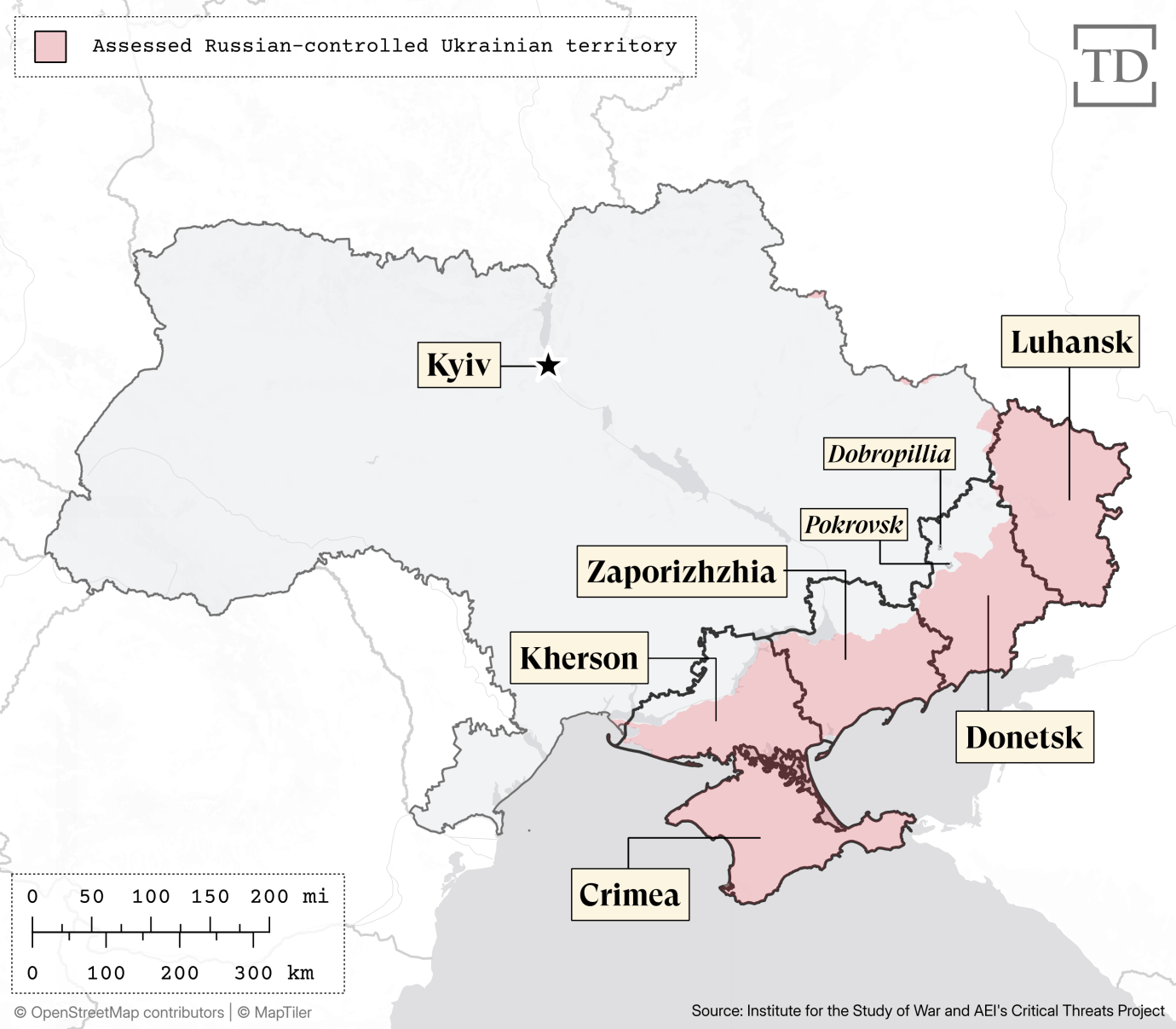

Though this week’s negotiations could determine Ukraine’s fate, they’ve come together with very little input from Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky. Last week, White House special envoy Steve Witkoff met with Putin at the Kremlin, returning with a ceasefire offer from the Russian president: Ukrainian troops would withdraw from the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, Russia’s 2014 conquest and annexation of the Crimean Peninsula would be internationally recognized, and in return, Russian forces would agree to a full truce.

The pitch was good enough for Trump to set a date for negotiations, although he cautioned that it was not a “breakthrough.” The president agreed to hold off on imposing threatened sanctions on Russia, which were set to take effect last Friday, and scheduled a meeting in Alaska for the end of this week. It was not, however, good enough for Ukraine and its European allies. After being briefed by White House officials last week on the Russian proposals, European leaders were reportedly unclear on the exact details of the Russian offer. But they were clear that Ukraine had to have a seat at the table.

“Ukraine’s future cannot be decided without the Ukrainians, who have been fighting for their freedom and security for over three years now,” wrote French President Emmanuel Macron on social media Saturday. Later in the week, top European officials presented their own peace proposal to the White House, demanding firm security guarantees for Ukraine—including potential NATO membership—in any postwar settlement.

Zelensky was even more blunt. “Any decisions made against us, any decisions made without Ukraine, are at the same time decisions against peace,” he said in a Saturday video address from the presidential office. “They will bring nothing. These are dead decisions; they will never work.” Zelensky also rejected the suggestion, made by Trump on Friday, that an eventual peace deal could include swapping some Ukrainian territory not controlled by Russia in order to regain occupied lands.

In response, Trump said that he was open to Zelensky’s participation in a future meeting, even if the Ukrainian leader would not attend the Alaska summit. It was a marked shift from Trump’s rhetoric earlier in his term, when he repeatedly blamed Ukraine for starting the war and expressed reluctance to impose more sanctions on Russia. But faced with Russian intransigence in negotiations, Trump threatened to impose sanctions on countries that buy Russian oil, a critical source of revenue for Moscow, starting August 8—a deadline that has now been moved to August 27.

On Sunday, Vice President J.D. Vance told Fox News that while Putin had initially refused to meet with Zelensky, “the president has now got that to change.” He also claimed that the U.S. was discussing “scheduling and things like that around when these three leaders could sit down and discuss an end to this conflict.”

But even as diplomatic deal-making accelerates, Russian troops continue to steadily advance in eastern Ukraine, gaining roughly a few dozen square miles per week. “They’re advancing faster than they were this time last year,” Rob Lee, a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute who recently returned from a tour of the Ukrainian front, told TMD. Lee noted that Russia has significantly improved its tactics and drone capabilities, integrating drone teams, like the elite Rubikon unit, with small-unit infiltration tactics to penetrate Ukrainian lines.

Kyiv is also facing an acute manpower shortage. Spread thin along a long defensive front, the Ukrainian Army is struggling to recruit or conscript enough troops for the infantry, as many Ukrainians balk at the long tours of duty now required on the frontline. “It creates this potentially vicious cycle,” said Lee. “It’s really important that Ukraine can improve the way they’re recruiting and employing infantry, because that’s still the biggest challenge on the frontline.”

In some places, according to some experts and former soldiers, a dozen soldiers can be responsible for up to six miles of frontline, making Russia’s infiltration tactics that much more effective. Russia has also massively expanded its recruitment and conscription efforts from earlier in the war: Moscow now claims that it has more than 600,000 troops deployed in Ukrainian territory, compared to Ukraine’s 300,000 frontline troops.

Ukraine has attempted to close the gap, lowering the draft age to 25 to 27 last year, granting amnesty to AWOL soldiers who return to their units, and increasing the financial incentives for volunteers. However, early efforts have had mixed results.

And concerning developments emerged along the frontline on Monday afternoon. In Donetsk, Russian forces broke through Ukrainian lines east of the town of Dobropillia, near the strategically important city of Pokrovsk. “This might be a tactical breakthrough,” noted Lee, although it remained to be seen whether the Russian Army could convert the roughly six-mile salient into a lasting gain. If they succeed, the chances of Russia occupying most of the Donbas by year’s end will rise.

But the Ukrainian armed forces are far from collapse. Even if Russia succeeds in taking the rest of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, Lee noted, their fall is unlikely to have a domino effect on the rest of Ukraine. And Ukraine has continued to carry out smaller-scale versions of its daring long-range drone strikes on Russia’s heavy bomber fleet in June. On Sunday, Ukrainian drones struck an oil refinery in Russia’s Komi Republic, more than 1,200 miles from the border.

Meanwhile, the Ukrainian public remains opposed to making major concessions to Russia. While 69 percent of Ukrainians now favor seeking a negotiated end to the war as soon as possible, 52 percent oppose ceding territory to Russia, with that number rising to 78 percent when asked about territory that Russia does not currently occupy. “Ukrainians are a nation that does not trade its own territories,” wrote former Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko on Facebook last week.

But Russia has its own reasons for fighting on, Nicholas Fenton—an associate director for the Europe, Russia, and Eurasia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies—told TMD. “At the current level of sanctions pressure, the current level of battlefield intensity, the Russians can continue to fight on,” he said, with their army sustained by massive recruitment efforts and their economy buoyed by military spending.

Putin, therefore, may simply be using the Alaska talks as a way to buy time, Fenton noted. “He’s a former KGB agent,” he said. “He’s going to want to try to flatter Trump into some sort of degree of satisfaction with the results of the summit and keep him on side.” Trump has certainly displayed a predilection for splashy diplomatic summits in the past, and might be mollified by the perception that Putin is engaging in the peace process, even as Russian forces press forward in Ukraine. The White House already has refrained from enacting more sanctions on Russia, and, on Sunday, Vance—long an advocate for limiting U.S. involvement in Ukraine—stated that the U.S. was “done with the funding of the Ukraine war business,” although he noted it would still sell arms to Europe that would be used by Ukraine.

Vance’s boss also signaled on Monday that the U.S. might be ready to wash its hands of the war. “At the end of that meeting, probably the first two minutes, I’ll know exactly whether or not a deal can be made,” Trump told reporters, calling the Friday summit a “feel-out meeting.” If Putin doesn’t seem amenable to a deal, which he claimed would include land swaps, Trump said that he may tell the Russian president, “lots of luck, keep fighting.”

On Monday afternoon, Zelensky predicted the latter outcome. The Russian president “is definitely not preparing for a ceasefire,” Zelensky said on X. “Putin is determined only to present a meeting with America as his personal victory and then continue acting exactly as before.”