from the will-they-never-learn dept

Two headlines walked into a UK courtroom: the BBC says “Wikipedia loses challenge,” while the Guardian says “Wikipedia can challenge if the strictest rules apply.” Annoyingly, both are true—and that split-screen is a perfect microcosm of what’s wrong with the UK’s Online Safety Act.

The core issue is whether or not Wikipedia would be considered a “Category 1” service, which, while size-gated like the DSA’s “Very Large Online Platform” (VLOP) concept, comes with a different bundle of duties (e.g., “user empowerment” filters and ad-fraud prevention obligations) and a different theory of risk. Category 1 services are required to do a whole bunch of things, many of which would be at odds with Wikipedia’s promises to be a worldwide information source, without compromising user safety or privacy (for example, it would likely require Wikipedia to verify the identity of many of its contributors).

So Wikipedia sued to challenge not the OSA as a whole, but just the categorization rules, which it feared would have it declared a Category 1 service by Ofcom.

In a detailed ruling, the High Court rejected Wikimedia’s core, up-front bid to torpedo the threshold regulations, basically arguing that because Ofcom has yet to declare Wikipedia as a Category 1 service, then it is not yet a “victim” of the law. The judge notes that it is not clear that Wikipedia will qualify as a Category 1 service at all:

In particular, I do not accept that it is “likely” that Wikipedia is a Category 1 service. The furthest that Ofcom has gone is to say that it might be. The Secretary of State’s officials considered only that it was a “possibility” (whereas other services were “likely” to qualify).

The judge also said that even if it were found to be a Category 1 service, it might not violate the European Convention on Human Rights to force Wikipedia to verify identities… because the judge believes that there is some convoluted scheme to have Wikipedia contributors verify themselves that wouldn’t be problematic (that’s… just wrong).

I do not, however, consider that it is inevitable that the application of Category 1 status to Wikipedia would necessarily result in a breach of Convention rights. That may depend on how the Code of Practice (compliance with which is deemed to achieve compliance with the statutory duties) operates. One of Wikipedia’s primary concerns is the requirement to enable users to choose only to encounter content from users whose identity has been verified. I accept that this runs completely counter to Wikipedia’s operating model (which has, on the evidence, been shown to be effective in promoting freedom of expression whilst promoting a high quality of content). There may, however, be ways to accommodate the requirement without causing undue damage to Wikipedia’s operations. It may, for example, be possible to ensure that users who make the requisite choice are only able to access pages where every editor who has contributed to the live content on the page has verified their identity. It is not obvious that this would be unduly difficult to achieve. It would mean that such users would only be able to access a small subset of Wikipedia’s content, but that would be their free, autonomous choice. It may well be that only very few people would make that choice, and that might then raise a question as to the proportionality of the entire exercise.

He also noted the plodding process: Ofcom has only just sent information notices (Wikimedia got one on March 27 and responded May 16), the register of Category 1 services comes first, and the relevant Codes of Practice won’t be in force “before 2027.” In other words: years of uncertainty by design.

But here’s the part many folks will miss: the judge also went out of his way to say Wikipedia “provides significant value for freedom of speech and expression,” that this ruling is “not… a green light” to impede Wikipedia’s operations, and that if Ofcom later jams Wikipedia into Category 1 in a way that breaks Article 10, Wikimedia can challenge Ofcom—and the Secretary of State may be obliged to amend or carve out the regs.

I stress that this does not give Ofcom and the Secretary of State a green light to implement a regime that would significantly impede Wikipedia’s operations. If they were to do so, that would have to be justified as proportionate if it were not to amount to a breach of the right to freedom of expression under article 10 of the Convention (and, potentially, a breach also of articles 8 and 11). It is, however, premature to rule on that now. Neither party has sought a ruling as to whether Wikipedia is a Category 1 service. Both parties say that decision must, for the moment, be left to Ofcom. If Ofcom decides that Wikipedia is not a Category 1 service, then no further issue will arise.

Doors remain open. Lawyer time remains billable.

Which is exactly the problem. The OSA was drafted so vaguely and bluntly that a non‑profit, collaboratively edited encyclopedia now has to spend all this time, money, and effort playing administrative Calvinball just to preserve the thing almost everyone agrees is good.

The court’s summary reads like a warning label lawmakers refused to print:

- Ofcom’s advice was deliberately generic and “service-agnostic” because recommender systems are opaque and constantly changing. Translation: we don’t actually know how any of this works in practice across wildly different services, but we’re regulating as if we can fit them all into simple buckets anyway.

- To be Category 1, you need big UK user numbers plus features Ofcom says correlate with virality in its “content recommender system.” However, the definition of a “content recommender system” is so broad it might swallow moderation tools like Wikipedia’s New Pages Feed—tools used by a tiny subset of volunteer editors to catch low‑quality edits quickly, not to turbocharge “going viral.”

- The judge basically says, look, this is a bright-line policy choice in a complex area; it will be over‑ and under‑inclusive by design. If Wikipedia gets caught, your remedy is: fight Ofcom, then maybe get the government to tweak the rule later.

Be real. For Meta or Google, this is Tuesday. For Wikipedia—the site that runs on donations and volunteer labor—this is an expensive, chilling time sink. And for the rest of the internet, it’s a preview of how the OSA turns governance into “prove you shouldn’t be crushed.”

As I wrote just recently about the OSA’s rollout, the law is already delivering exactly the harms critics predicted: invasive “age assurance” checkpoints, mass migration to VPNs, and collateral damage to health, safety, and news content—while small communities shut down or get fenced off behind ID walls. The only players that can comfortably absorb this are the largest commercial platforms, which… somehow always seems to be the point.

This ruling doesn’t fix any of that. It entrenches the architecture:

- Legislators set category thresholds using mushy, one‑size‑fits‑all tech abstractions (recommenders! shares!) and massive user counts.

- Ofcom does “indicative” assessments that (by its own admission) can’t discern how those features actually work across sectors.

- Nonprofits and smaller communities get told: if you’re swept up, litigate later; maybe government officials will bail you out if the damage is obvious enough.

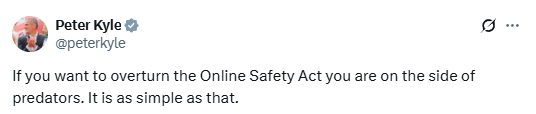

And, remember, the government official in charge of a potential “fix” recently said anyone criticizing the OSA was on the side of child predators.

Meanwhile, the most fraught duty looming for Category 1—adult “user empowerment” filters that let people block all content from non‑verified users (OSA’s Section 15)—is fundamentally incompatible with Wikipedia’s collaborative model. The judge’s “subset of pages where every editor has verified” workaround would balkanize articles, shatter the integrity of collaborative editing, and create a perverse incentive to link real‑world identity to speech—exactly what Wikipedia’s governance model (and basic safety) try to avoid.

The OSA keeps forcing square pegs through round compliance holes, then tells courts to mop up the mess with proportionality after the fact.

A couple clarifications worth nailing down, because sloppy narratives help bad law:

- “Wikipedia lost.” Procedurally, yes: Wikimedia didn’t blow up the thresholds. But the court explicitly invited future challenges if Ofcom’s classification or the downstream duties impede Wikipedia’s operations or chill speech. Both things can be true.

- “Wikipedia can challenge later.” Yes—and that’s… bad? It means the standard posture is “comply first, sue later,” which advantages giant incumbents and punishes public‑interest infrastructure. It also leaves a ton of uncertainty on the backs of a non-profit who has better things to focus on.

If lawmakers genuinely wanted to avoid this farce, they had tools: narrowly tailor the definitions so that this wasn’t such a guessing game. Maybe scope certain features, like “forward/share” to end‑user distribution features, not moderator utilities; build a clear exemption path for sites with demonstrably low risk profiles. Or maybe just have Ofcom do the hard, service‑specific work before writing the rule, not after.

Or maybe just stop falling for the exaggerated moral panic that we can magically make the internet perfectly safe for kids by putting more and more rules on internet services, instead of better teaching kids how to use the internet appropriately.

Instead, we got “we’ll fix it in post.” The court just confirmed that the only safety valve is more process, more guidance, more codes of practice, and maybe—maybe—a future amendment if the damage becomes undeniable.

As I said in my recent OSA article: this is regulation written as if the internet is only Facebook and Google; the giants glide, everyone else bleeds. This ruling doesn’t change that. It spotlights it.

The UK can keep pretending this will all shake out in proportionate, sensible ways once Ofcom finishes the paperwork. Or it can accept what’s already obvious: a law that makes Wikipedia litigate for the right to keep being Wikipedia is a law that’s broken at the premise.

Filed Under: free speech, intermediary liability, ofcom, online safety act, platform regulation, uk, uncertainty, verification

Companies: wikimedia, wikimedia foundation