The fall is coming and, with it, school. As parents, we have all the usual concerns. Did my kid get the best homeroom teacher? Do we have the right pencils? When is pajama day, and can they please give us more notice this year?

To this, many parents have added a new worry: Is my child’s class now full of a bunch of unvaccinated kids? There is a lot of discussion in the media and in parent groups about vaccine skepticism, declines in vaccination rates, and the possible risks of having fewer children vaccinated. The Kaiser Family Foundation recently issued a report showing vaccination rates declining among kindergarteners. The resulting confusion may leave parents wondering: How much should I worry about this? Do I need to vet possible playdates for their family’s vaccine views?

To get to some answers, it’s helpful to go to the data on a few questions. First, how much are vaccination rates really falling? Second, is our new health and human services secretary, longtime vaccine skeptic Robert F. Kennedy Jr., making people more wary of vaccines? Third, where might we go from here? And, finally, should you cancel those playdates?

How much are vaccination rates really changing?

There is much discussion of this in the media, but it’s worth both right-sizing and localizing this concern.

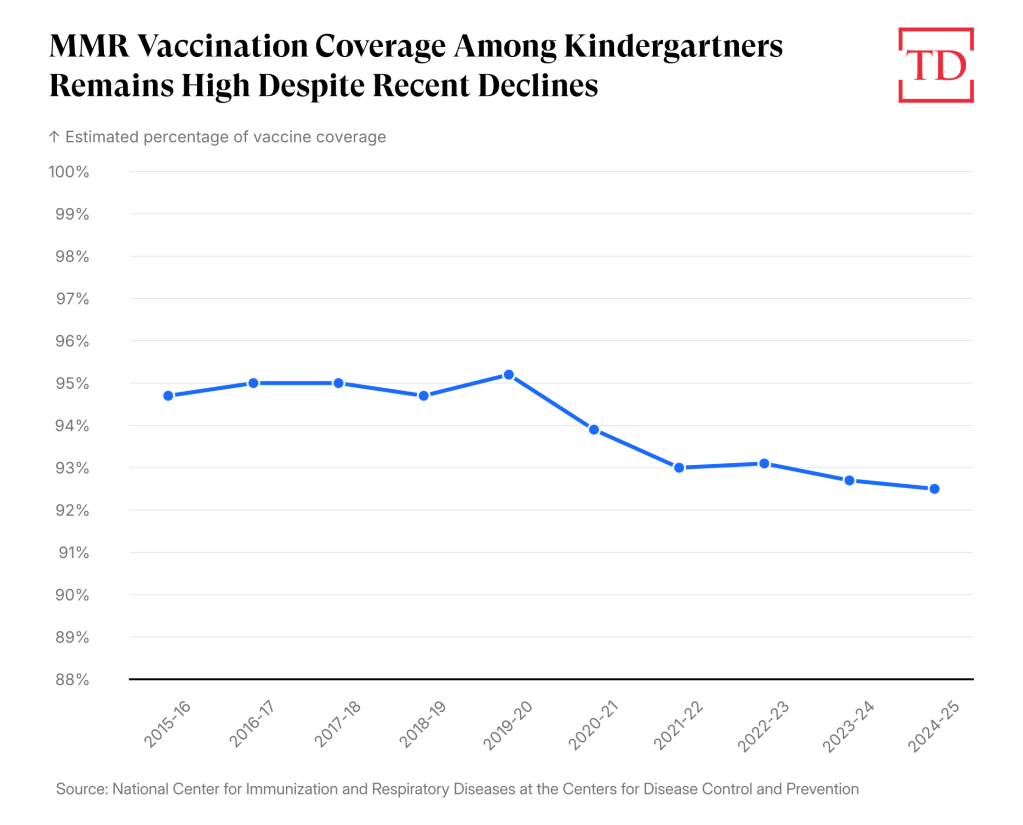

Despite the rhetoric and volume of discussion in the media, the actual change in vaccination rates over time has been small. The graph below shows vaccination rates for measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR), a combination vaccine, reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for children entering kindergarten nationwide since the 2016-2017 school year. The current MMR vaccination rate is 92.5 percent, down from a peak of 95.2 percent in the 2019-2020 school year. This is a meaningful decline, to be sure, but it is still the case that the vast majority of kids entering kindergarten are fully vaccinated.

Other common childhood vaccines look very similar, including DTaP (protecting against diphtheria, tetanus, and whooping cough), chicken pox, hepatitis B, and polio. All have declined some over time, with the biggest year-over-year drop during the pandemic.

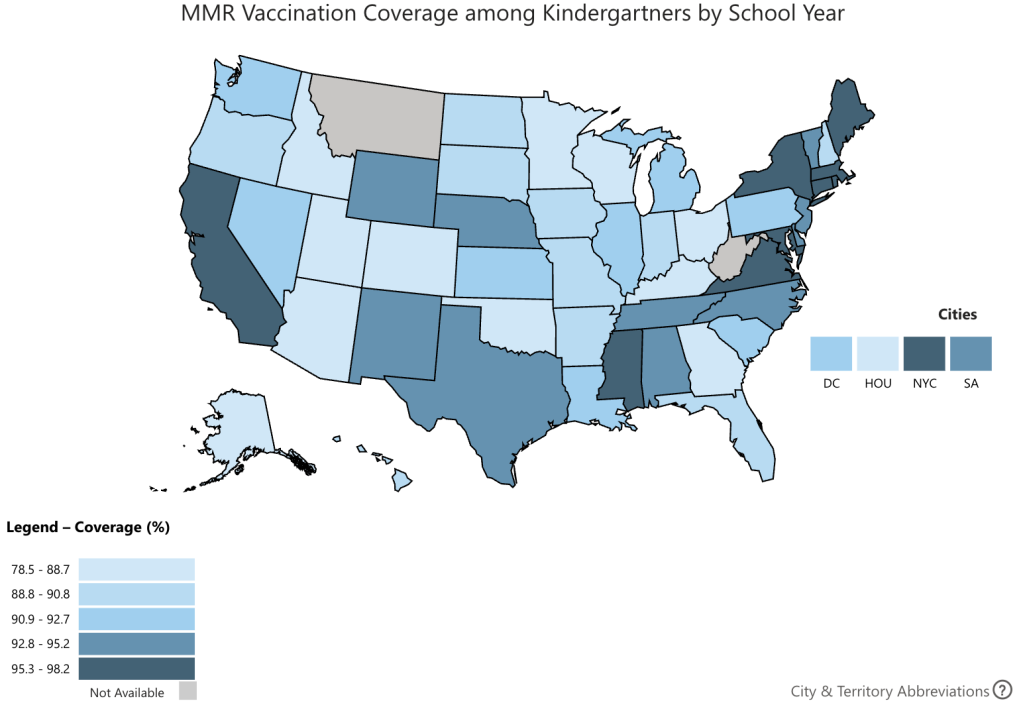

Another important point is that vaccination rates vary widely from state to state. The CDC has a helpful map that shows this at the state level. In Idaho, for example, 78.5 percent of kindergarteners have the MMR vaccine. In Connecticut, it’s 98.2 percent.

For measles, the vaccination rates to achieve “herd immunity” are 92 percent to 95 percent—meaning that if vaccination rates are at or above that level in a community, even those who are unvaccinated are likely to be protected against the disease. The relevant community is a small one—if you live in Connecticut, with a 98 percent vaccination rate, the risk of a measles outbreak is extremely small, even though vaccination rates in Idaho are lower.

In fact, what really matters is even more local: the vaccination rates at your child’s school or school district, and those can vary enormously. Data from California before the state tightened its vaccine exemption policies in 2016 showed some schools with vaccination rates as low as 13 percent, even as the state’s overall rate was 93 percent.

Both of these points reinforce the idea that for most people, it’s likely the vaccination rates where you live and where your child attends school are very high.

The RFK Jr. factor.

I have been completely appalled at the rhetoric on vaccines coming out of the Trump administration, as I think many people have been—including people on both sides of the political aisle. Kennedy’s long-held position on vaccines is fringe, and there is a significant amount of data that refutes his claims about, for example, a link between vaccines and autism.

However, RFK Jr. has been running the Department of Health and Human Services only since January, so in explaining the declines in vaccination rates that we have seen in the past several years, we cannot put blame for recent rate trends at his feet.

Looking at the graph above, there is a clear decline in vaccination rates that corresponds with the COVID pandemic. During the pandemic, a lot of standard pediatric care was disrupted, including routine vaccinations. The conflicts over the COVID vaccine—discomfort with vaccine mandates, misinformation around vaccine safety profiles, concerns about overuse of boosters for children—have all contributed to a distrust of the COVID vaccine, especially on the political right. That distrust seems to have spilled over to other vaccines, leading to persistently lower vaccination rates overall.

Looking not just over time but across geographical areas, some localities have lower vaccination rates than others, and a major determinant of this is state or school rules about vaccine exemptions. States that allow religious or, especially, personal exemptions from school-based vaccine mandates tend to have lower vaccination rates.

We can see this very starkly in 2016 in California. Prior to 2016, California allowed many vaccine exemptions, including a personal belief exemption. As a result, a third of children lived in counties with measles vaccination rates below 90 percent. After a 2014 measles outbreak, the state tightened the rules considerably, and the California State Legislature passed a law in 2015 that prohibited parents from claiming exemptions from vaccinations based on philosophical or religious beliefs. Exemptions were granted only for medical reasons. In the first year after that law took effect (the 2016-2017 school year), less than 1 percent of children lived in counties with vaccination rates below 90 percent.

This is all to say: The current situation, both the decline in vaccinations and the geographic variations of those rates, is likely not a result of RFK Jr.’s recent moves in particular.

Where do we go from here?

Based on the recent trends, we might expect continued small declines in vaccination rates. There are at least three reasons, however, to be concerned about more dramatic changes given the current leadership in Washington, D.C.

First, Kennedy has brought vaccine skepticism into the mainstream of news and culture, and reinforced even more casual concerns about vaccines that some parents have. In my own discussions with parents, I’m seeing much more vaccine hesitancy and many more questions than I once did. Is there really a reason to get the hepatitis B vaccination at birth? My sister-in-law says we should space out all of our vaccines – is that better? My husband is worried about vaccines and autism. What can I tell him? Pediatricians I speak to have also told me they are spending more time with parents discussing vaccination choices.

Current kindergarten vaccination rates are a lagging indicator; we may see new parents in the next year or two vaccinate their children at much lower rates.

Second, the administration may push states to make vaccine exemption policies looser, encouraging more states to allow for personal belief exemptions and reversing trends toward higher vaccination rates like California experienced. Based on what we know from the data, this is likely to lower vaccination rates.

Third, Kennedy has made some moves that could lead to changes in insurance coverage for vaccines or even approvals. Smart people, such as Dr. Paul Offit, a pediatrician and leading authority on vaccinations and infectious diseases, have argued that Kennedy’s long-term goal may be the elimination of childhood vaccines. This feels unlikely given that the American Academy of Pediatrics has maintained its existing vaccine schedule, and most Americans still do want to vaccinate their children. Still, it seems like a legitimate concern.

Overall, the fact that current vaccination rates are lower than they were in 2019-20 is not something this administration has engineered. But the rhetoric from some officials and some of Kennedy’s moves pertaining to vaccines have created the possibility that in the future, the changes will be even more extreme and damaging.

So … should you have that playdate?

Here is the good news, at least for parents of school-aged children: If your child has been vaccinated, they are extremely well protected against illness. The measles vaccine is 99 percent effective after two doses. So while I would never encourage you to seek out exposure to measles, if your child happens to be exposed, they are protected. The same can be said for other vaccines (DTAP, chicken pox, etc). If you’ve got a fully vaccinated kid, feel free to make whatever playdates your child would like, regardless of whether a potential playmate’s family has a different take on vaccination.