On August 11, Trump signed a pair of executive orders giving the White House control of city police forces and mobilizing the National Guard to address what Trump characterized as a crime “emergency.” In the days following, roughly 800 members of D.C.’s National Guard and 500 federal law enforcement officers from various agencies took to the district’s streets, bolstered by small contingents of National Guard from Ohio, West Virginia, and South Carolina. More troops from Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana are reportedly on the way. Much of the Guard deployment is of dubious legality, observers say, and won’t fix the structural issues with D.C. policing. But it’s also likely to have at least a short-term impact on the city’s relatively high crime rate.

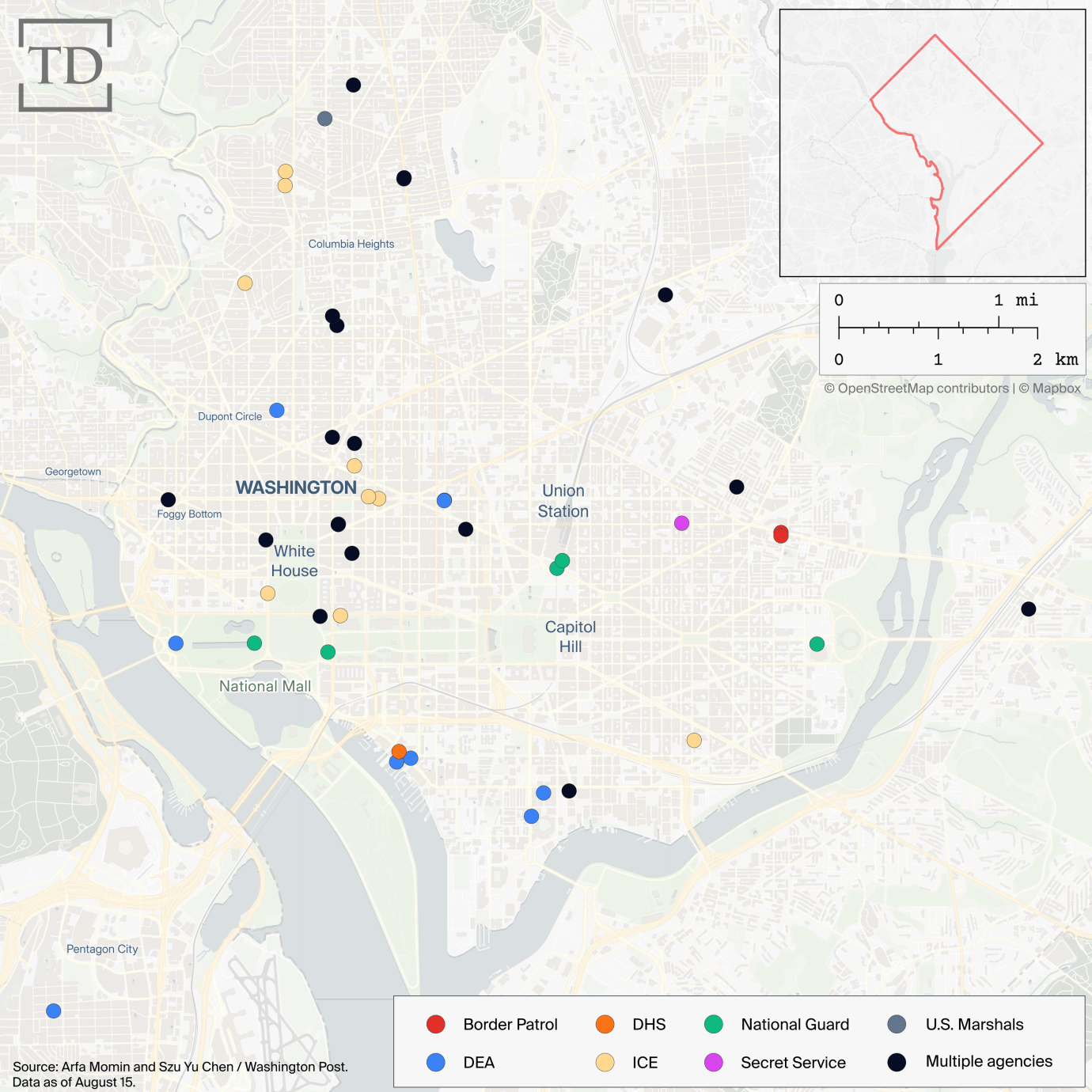

The federal deployment to D.C. can be split into three broad categories: troops activated from the capital’s own National Guard, various state contingents under the command of their respective governors, and federal law enforcement personnel, including officers from the Drug Enforcement Administration, the FBI, Border Patrol, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, U.S. Marshals, and the Secret Service.

Critics say federal personnel are focused on highly visible actions in low-crime areas—not the the areas local residents encounter the most crime—but the White House has countered that 101 out of 212 non-immigration-related arrests made between August 9 and 17 were in wards 7 and 8 (two of the city’s violent hotspots across the Anacostia River.) On Wednesday, U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi said federal law enforcement had so far made more than 550 arrests in total, at least 300 of which were related to immigration enforcement.

Even so, it’s indisputable that National Guard troops are essentially absent from the most dangerous neighborhoods. Instead, they are positioned in a shallow arc across southwest D.C., in tourist-heavy areas like the National Mall, Union Station, and Metro stops around the city.

Federal law enforcement officers also operate in these areas, but they have been scattered across the city, in both high and low crime areas. DEA and ICE officials have patrolled the gentrified Dupont Circle and Adams Morgan neighborhoods, FBI agents recently patrolled Georgetown, ICE and U.S. marshals conducted operations in the less-safe neighborhood of Columbia Heights, and Secret Service and Border Patrol agents made arrests in D.C.’s Northeast, a relatively high-crime area. In the quiet residential neighborhood of Mount Pleasant, a masked ICE agent tore down a poster with obscene anti-ICE slogans, telling a videotaping onlooker, “We’re taking America back, baby.” The video was posted to ICE’s official account on Sunday.

Guard soldiers were considerably less gung-ho. TMD spoke with nine soldiers, who all shied away from expressing opinions on their current mission and stressed their supportive role. “We can’t arrest or anything like that,” a D.C. Air Guard member told TMD outside the Pierre L’enfant Metro entrance. “We’re here to support law enforcement and just back them up.”

But he did say his unit had been trained in “basic apprehension and de-escalation” techniques, and he mentioned members of his unit had temporarily detained someone who had assaulted a police officer on the National Mall. That sort of incident appears to be relatively rare: TMD could not find any Guard members who had personally assisted D.C. police.

The Guard’s limited range of action is due to relatively strict legal constraints. “Their initial mission is to provide a visible presence in key public areas, serving as a visible crime deterrent,” the Army said in a statement last week. “They will not arrest, search, or direct law enforcement.”

With these parameters, the National Guard is on fairly solid legal footing, Mark Nevitt, a professor at Emory University School of Law and a former Navy JAG, told TMD. Protecting federal property and employees “would be consistent with existing legal authorities,” he said.

With almost a quarter of Washington’s land owned by the federal government, concentrated around downtown government buildings and the National Mall, Guard members have a lot of freedom of movement, he noted. But anything beyond that is “a thornier question,” Nevitt said. The D.C. National Guard isn’t subject to the Insurrection Act—the law that allows presidents to federalize state Guard troops for law enforcement purposes—as they’re already directly under Trump’s authority.

“It’s sort of an end-around the Insurrection Act,” said Nevitt. But he also said it’s an “open legal question” as to whether the Posse Comitatus Act, which criminalizes the use of the military for law enforcement in the absence of the Insurrection Act being invoked, or in certain specific support roles, applies to D.C.’s Guard. If D.C. Guard troops actively assisted federal or local law enforcement, there’s simply no judicial precedent, outside of a few opinions from the Department of Justice, for dealing with the situation.

For the state Guard contingents beginning to arrive in Washington, the situation is even less clear. “They haven’t been deputized under D.C. law to arrest,” said Nevitt, although he noted that the use of state Guards to enforce the law in the absence of the Insurrection Act would likely be criminal.

But legal complications are separate from the Guard’s effectiveness at deterring crime. “I would expect to see some effect,” Peter Moskos, a professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice and former police officer, told TMD. He pointed to evidence from rapid large-scale deployments of federal personnel to D.C. during terror alerts in the early 2000s, creating a noticeable drop in crime.

The effect, said Moskos, is twofold. First, Guard troops performing relatively simple duties like standing by Metro stops free up D.C. police for more proactive missions. The mere presence of uniformed personnel can also deter crime, simply by fostering a sense that the government is focused on law enforcement.

Several hundred more law enforcement personnel patrolling the streets will likely intimidate criminals. Beyond this, Rafael Mangual—an expert on crime and policing at the Manhattan Institute—told TMD that incarcerating criminals who are likely to reoffend could reduce street crime for years. “Even [getting] a few hundred gun-toting criminals off the street, for a multiyear prison term, can yield significant benefits of public safety over time,” he noted.

The question, both Mangual and Moskos said, is whether U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia Jeanine Pirro and the Metropolitan Police Department can translate this relief into sustainable long-term gain. Metropolitan Police staffing levels are currently at a 50-year low, and coordination between D.C. police and the U.S. attorney’s office and criminal justice system remains difficult.

“It is a good way to get things under control in the places where these officers are being deployed,” Mangual said. “But when they leave, D.C. is still going to need to have an answer for the things that have been driving crime over the long term.”