Introduction

In July 2025, the New York City Charter Revision Commission (NYC CRC) appointed by Mayor Eric Adams approved five November ballot questions proposing revisions to the city charter, the document establishing the structure and functions of city government. This brief addresses the first three questions, which, taken as a whole, represent a major restructuring of the land-use approval process. In particular, the mayor would gain power, at the expense of the city council, on actions that facilitate housing production.

The brief concludes that the enactment of the proposed amendments in the citywide referendum scheduled for the fall would be good for the city. However, newly empowered city planners and city housing officials should use those powers constructively. Not doing so invites a future political backlash against new housing construction, as has occurred in the past.

Table 1 summarizes the three ballot proposals changing the land-use approval process.[1]

Table 1

| Ballot Proposal | Current City Charter | Proposed Change |

| 1 | All zoning changes must be approved by the City Planning Commission (CPC) and the city council. The Board of Standards and Appeals (BSA) may issue site-specific zoning variances, provided that stringent standards are met. | For rezonings facilitating affordable housing in 12 community districts identified as having the smallest proportional increase in affordable housing, a fast-track approval process is instituted, requiring only the approval of the CPC and not the city council. The BSA may issue site-specific zoning waivers for publicly financed affordable housing projects under less stringent criteria. |

| 2 | All zoning changes must be approved by the City Planning Commission and city council. | In medium- and high-density zoning districts, a fast-track approval process is instituted for zoning changes increasing permitted floor area by not more than 30%. In low-density zoning areas with a standard height of not more than 45 feet, any zoning change is subject to the fast track. The fast track requires only the approval of the City Planning Commission, not the city council. Specified additional land-use actions are also eligible for the fast track. |

| 3 | The mayor may veto a city council disapproval or modification of a zoning change approved by the City Planning Commission. The council may override the mayor’s veto by a two-thirds vote. | For zoning changes that facilitate the creation of affordable housing and require city council approval, an Affordable Housing Appeals Board is created, comprising the mayor, city council speaker, and relevant borough president. Where the council disapproves or modifies a zoning change, the board by a two-thirds vote may reinstate the terms of the City Planning Commission’s approval, in whole or in part. |

Years ago, New York City gave up its reputation as a city on the cutting edge of urban policy. That is particularly true of housing, where NYC led the way in the 1930s on public housing, in the 1940s on urban renewal, and in the 1960s on zoning reforms intended to reduce built densities and adapt cities for the automobile age. Subsequently, and in a welcome contrast with earlier misguided and damaging policies, NYC was a leader in historical preservation, adaptive reuse of obsolete commercial and industrial buildings, and zoning rules that promote active and appealing streetscapes.

But in recent years, important innovations in housing policy have occurred in other places. The YIMBY (Yes-In-My-Backyard) movement has swept states and cities across the country, advocating for land-use deregulation and streamlined approval procedures to address widespread housing supply shortages. New York was a laggard—and suffered for it, as a chronic housing shortfall worsened. In an initial effort to address a vast housing need by lifting unnecessary regulatory burdens on private investment, the city council enacted in late 2024 the Adams administration’s “City of Yes for Housing Opportunity” (COYHO) zoning reforms. While helpful, the scaled-back version of the amendment passed by the city council again revealed the political constraints on pro-housing policies.[2]

COYHO was the one major citywide pro-housing zoning initiative possible in Mayor Eric Adams’s four-year term. This is a consequence of time-consuming procedural requirements lasting more than two years. These included widespread outreach to community boards, elected officials, and other interest groups; preparation of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS); and the city’s multilevel city charter–mandated public review process.[3]

This zoning amendment was notable in that Mayor Eric Adams and City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams assembled a majority coalition of council members to vote in favor, but the zoning changes have effect citywide, including the districts of those members who voted against. The council thus overcame the practice of “member deference,” which gives members a de facto veto over land-use changes in their districts. There was nonetheless a great deal of deference to opponents’ concerns, as the council majority scaled back changes approved by the City Planning Commission (CPC) in ways that will result in less housing production in the districts of council members who were opposed.[4] For example, COYHO, as originally approved by the CPC, removed off-street parking requirements for residences throughout the city. Many of the members who voted “no” saw the complete or partial restoration of off-street parking requirements in their districts.[5] In the areas with restored parking requirements, new housing will be costlier to construct.

I wrote earlier this year that with 2025 and 2026 election years for mayor and governor, respectively, “the outlook for aggressive pro-housing actions . . . is not promising.”[6] However, the Adams administration had one more daring citywide initiative to come in 2025: the appointment of the CRC.

The proposed land-use process amendments are intended to address, in a substantive way, concerns about the length of the approval process for new housing and the practice of “member deference” on the city council, which deters land-use applications to add housing in the districts of members known to be opponents.[7] The amendments would be the first substantive changes to the city charter land-use process (known as the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure, or ULURP) since 1989, when the city council became the final decision-maker on zoning and other land-use regulations.[8] The current CRC proposes to shift power from the 51-member city council to the CPC, the Board of Standards and Appeals (BSA), the five borough presidents, and the city council speaker. The CRC hopes thereby to speed up approvals for publicly assisted housing, lowering process costs for developers and delays that increase total project costs. It also hopes to make zoning changes more predictable and less costly to obtain, thereby encouraging more private applicants. The CRC’s final report states:

[T]he City’s existing process limits the City’s ability to build publicly financed affordable housing, particularly on City-owned land, delaying badly needed projects and raising costs of construction. [Additionally,] because the local councilmember functionally has the final say on a project, proposals for land use changes are vanishingly rare in the districts of councilmembers who are known to be opposed to additional housing, irrespective of citywide need. Further, the length, cost, and uncertainty of proceeding through ULURP means it almost never enables small changes. Because ULURP [applies] the same procedures to massive projects and modest ones, only large proposals—which will bring in enough revenue to justify years of costs prior to approval—are ever put forward.[9]

Charter Revision Commission Proposals

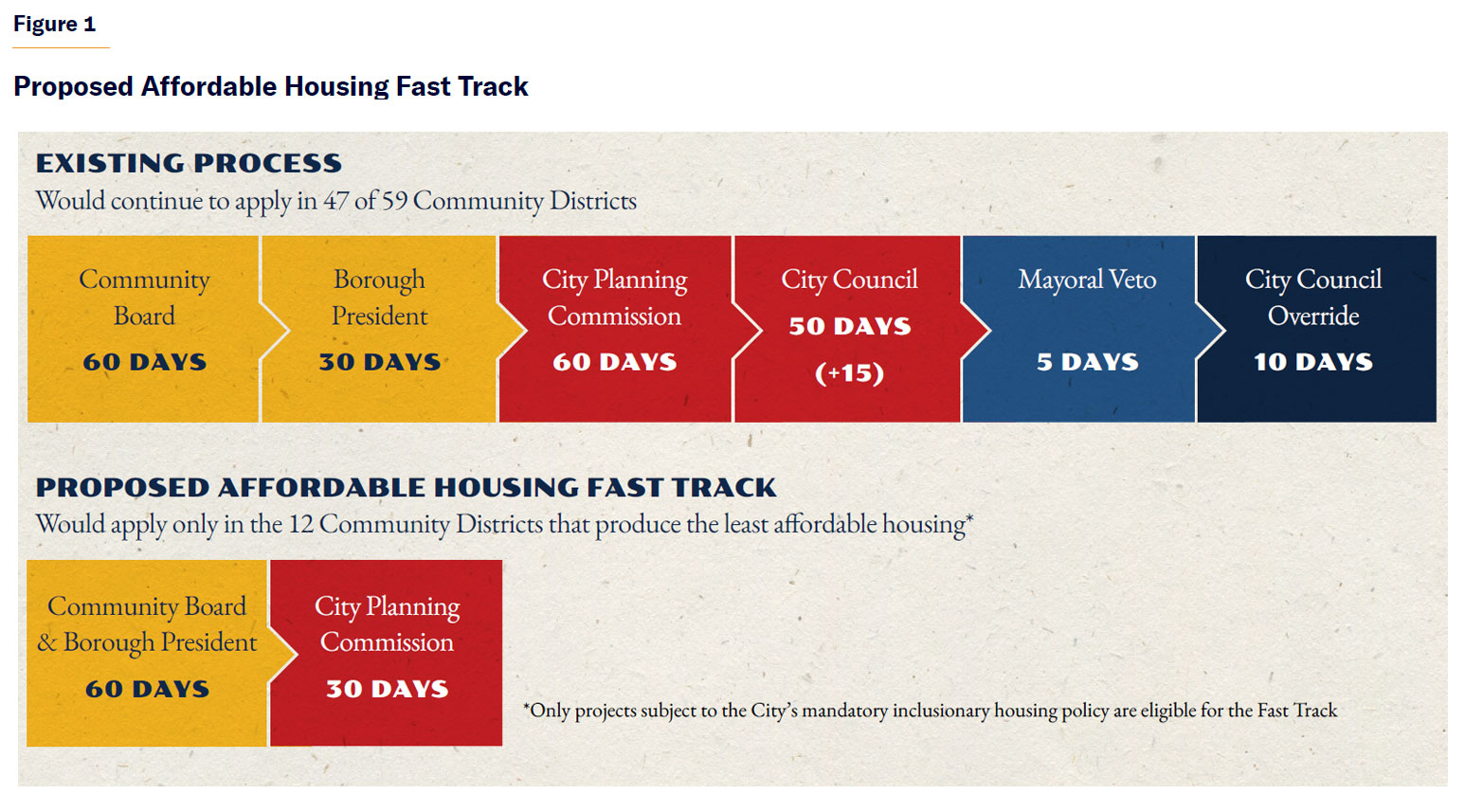

Ballot Proposal 1: Fast-Tracking Affordable Housing

The CRC proposes two separate changes[10] to speed up approvals of affordable housing and prevent recalcitrant city council members from blocking such housing in their districts. The first, summarized in Figure 1, would apply in 12 community districts, identified by NYC DCP, where the lowest numbers of affordable housing units, as a percentage of total housing units, have been produced in the previous five years. The list of community districts would be published by October 1, 2026, and every five years thereafter. “Affordable housing” is broadly defined to include housing units restricted by agreement with a government agency that limits residents’ incomes. In those community districts, and within a five-year window, rezoning applications subject to the existing Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) program[11] would be eligible for a special expedited land-use review procedure (ELURP). Under ELURP, rezoning applications would be referred concurrently to the applicable community board and borough president for 60 days.[12] As in the current process, the community board and borough president recommendations are advisory. The sole required and binding approval would be from the CPC, which would have 30 days to approve, modify, or deny the application, with an extra 15 days for applications that require an EIS, for which a more detailed staff review is needed. The application would not be referred to the city council for additional review and approval, as occurs today.

The proposed charter amendment further specifies the criteria that the CPC should use in determining whether to approve applications in the 12 community districts. These include consistency with the Fair Housing Plan already mandated by the charter and the adequacy of existing transportation, sewer, and other infrastructure.[13] Conspicuously absent is consideration of “neighborhood character”—consistency with the scale and character of the surrounding community, a finding that NYC’s planning commission, as well as others across the nation, typically has used to justify restrictive zoning and preserve low-scale housing, even as restrictively zoned neighborhoods become less affordable. The proposal clearly contemplates the creation of districts with a distinctly different, higher-density character in the 12 community districts, in order to support housing production and affordable housing goals.

The CPC comprises 13 members: seven appointed by the mayor; one each by the five borough presidents; and one appointed by the public advocate. However, except for the chair, who is appointed by the current mayor, members serve staggered five-year terms and thus may have been appointed by the current incumbent’s predecessor. In practice, this has not materially affected the incumbent mayor’s ability to get favored affordable or mixed-income housing applications approved by the CPC and block disfavored ones, usually by indicating to potential applicants early in the process that the application does not have administration support.

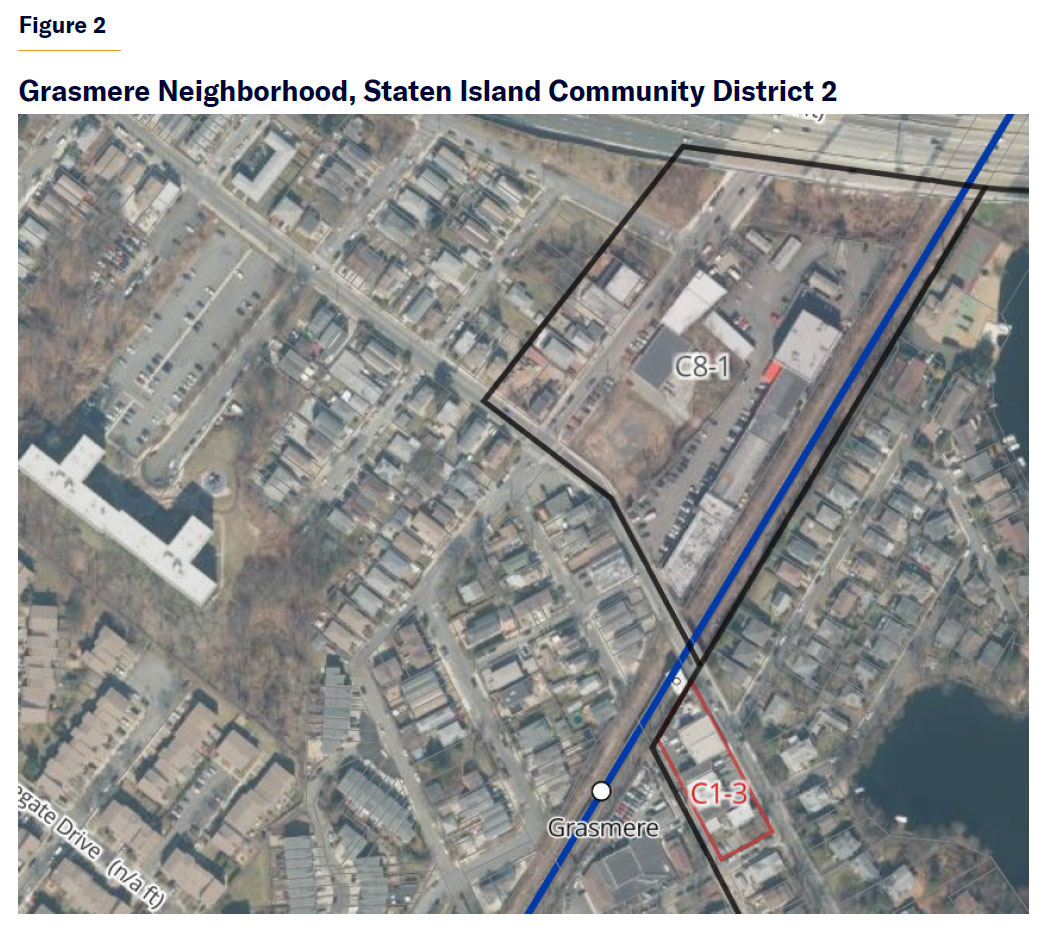

As an example of the type of rezoning affected by this change, one community district likely to be included among the 12 low-affordable-housing production areas is Staten Island Community District 2, where little housing of any description has been constructed in recent years. In a 2022 report, I identified the development potential in the Grasmere neighborhood, served by SIR rail transit (Figure 2).[14] Within a short walk of the station, a C8-1 zoning district allows no new housing. A nearby apartment building is surrounded by a large parking lot and vacant land that could be developed with more apartments but is restrictively zoned. While unlikely to get the council member’s support, a rezoning in this area could be achieved by a CPC empowered by the proposed charter change.

A second proposed city charter change in the “Fast-Tracking Affordable Housing” ballot proposal affects the BSA, which is currently charged with approving site-specific zoning variances, among other matters. The criteria for a variance are tailored to the legal requirement that zoning provides an avenue for relief to property owners experiencing bona fide hardship.[15] The criteria are intentionally difficult to meet, requiring unique physical conditions that create practical difficulties for a nonprofit applicant and financial hardship for a for-profit applicant. The BSA is also charged with granting site-specific special permits waiving various zoning provisions.[16] The charter change would create a new BSA waiver, easier to meet than a variance and more akin to a special permit. It would apply to any zoning use, bulk regulation, or parking regulation for a building used in whole or in part for affordable housing, provided that:

- The underlying zoning allows residential use.

- The subject building is owned in whole or in part by “a company that has been organized exclusively to develop housing projects for persons of low income.” This would include a Housing Development Fund Company (HDFC, the vehicle, regulated under state law, for most 100% affordable housing developments).

- The building complies with applicable city standards.

The BSA would need to find that the subject building could not be developed without the waivers. Additionally, the board would need to find that the proposed building would not alter the essential character of the neighborhood and that the benefits of the waivers outweigh any disadvantages. The inclusion of the “neighborhood character” finding here, but not in the CPC expedited approval in the 12 community districts, likely reflects concerns about the site-specific nature of the approval. Allowing one property owner in a neighborhood to construct a building substantially different from what others already have built, or are permitted to build, could raise concerns about impermissible “spot zoning,” i.e., zoning that benefits or harms particular property owners.[17] While the standards for spot zoning are somewhat nebulous, regardless of the charter language, the CPC would not typically approve mapping of a zoning district with distinctively denser parameters for an area comprising only one lot.

The BSA comprises five members, appointed by the mayor for six-year terms. As with the CPC, current members may have been appointed by the previous mayor. However, the incumbent mayor always has a strong influence on the board’s decisions. Given that every application under this provision will likely be a city-sponsored affordable housing project, significant opposition on the board is unlikely.

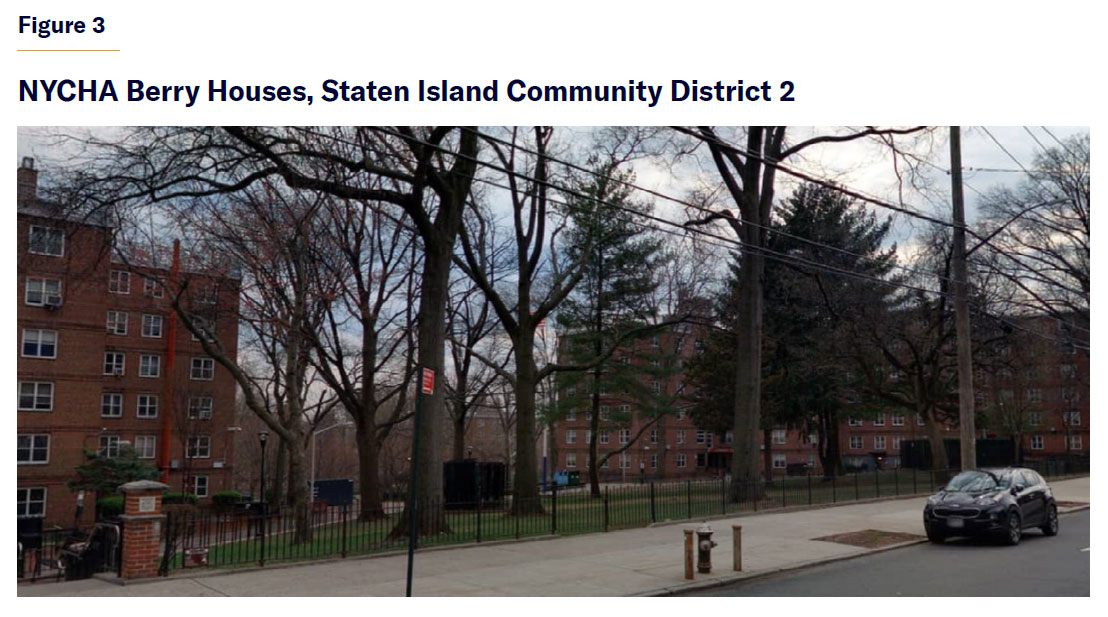

An example of the type of project that the BSA might approve also uses a potential housing site in Staten Island Community District 2. In the 2022 report, I pointed out the redevelopment potential of the NYC Housing Authority’s 506-unit Berry Houses, located near the Jefferson Avenue SIR station (Figure 3). This public housing development’s extensive open space could likely accommodate one or more new buildings of similar six-story scale.

Ballot Proposal 2: Simplify Review of Modest Housing and Infrastructure Projects

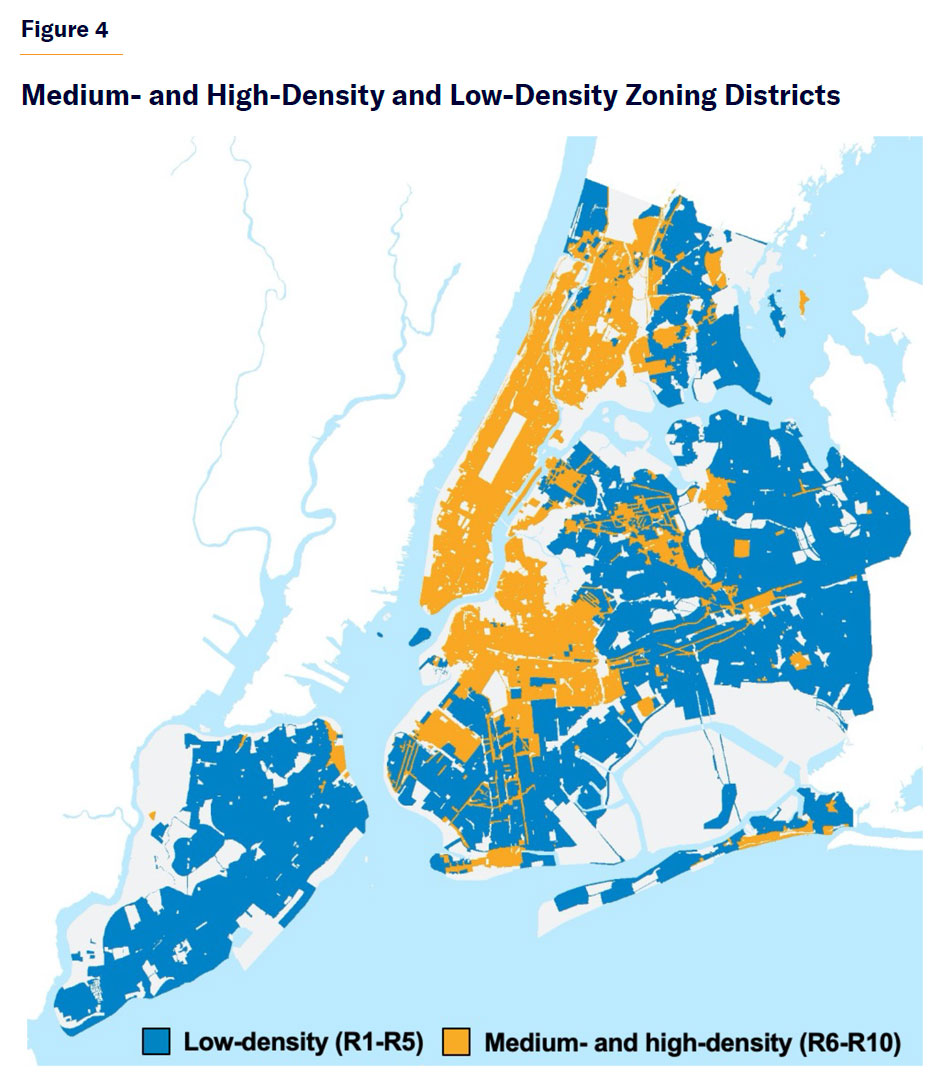

The CRC proposes that ELURP also apply to a specified group of land-use changes considered “modest.”[18] For zoning map changes, ELURP would apply only to changes that do not require an EIS. Different rules would apply in medium- and high-density districts and low-density districts. The CRC’s final report includes a map (Figure 4) depicting where these districts are mapped in the city.

In medium- and high-density districts, ELURP is proposed to apply to zoning district map changes in locations where housing is already allowed and that increase maximum residential floor area by not more than 30%.[19] The CRC’s Adopted Final Report notes that such relatively small changes are rarely seen in ULURP applications. It attributes this rarity to the cost and expense of ULURP.[20] Notably, the city’s policy in these districts is to apply in rezonings the forbidding math of MIH, which effectively requires that 25% or 30% of units be marketed at what are, in the best-case scenario, rents that cover operating costs but not amortized construction costs. Any property owner whose current zoning predates the policy’s advent in the de Blasio administration, and thus is not required to set aside affordable units at all, will seek a rezoning only if there is, in addition to the required set-aside, a large increment of market-rate housing (likely more than 30%) to support construction financing and provide for the desired return on investment.

ELURP won’t change the economic calculation much. Thus the main beneficiaries of this charter change in medium- and high-density districts will probably be property owners whose lots are already covered by MIH.[21] They will have an incentive to seek more floor area, since that won’t be subject to pushback from the local council member. For example, on East 116th Street in East Harlem, a row of low-rise commercial buildings sits in an MIH area, steps from a subway station at Lexington Avenue (Figure 5). The buildings are zoned R7D, at 5.6 FAR. That level of density has not been enough, thus far, to spur redevelopment of the block. With this charter amendment, the property owners might find that applying for a fast-track rezoning by the CPC to R8A (7.2 FAR, an increase of 29%) is in their best interest.

ELURP in low-density districts, as proposed, would be far more powerful as a spur to new housing. In these districts, ELURP could be used to map from any district to any other district, provided that the FAR of the new district does not exceed 2 and the maximum height permitted does not exceed 45 feet. Fortunately, the Zoning Resolution has a district that meets those parameters, called R5D, which is not widely mapped today but certainly could be in the future, were this charter amendment to be adopted.

Figure 6 shows a typical four-story R5D apartment building in Queens. ELURP would allow the CPC to accomplish widespread mapping of R5D in areas that now have restrictive zoning and see little new housing development, provided that such rezonings do not cross EIS thresholds. For example, near the Broadway Long Island Rail Road station at the eastern edge of densely populated Flushing, Queens, COYHO allowed some increases in zoned capacity for new housing through the “Town Center”[22] and “Transit Oriented Development”[23] proposals, but the city council cut out areas zoned for single-family homes from eligibility for the latter provision[24] (Figure 7).

Source: Screenshot from NYC DCP, Zoning and Land Use Map, Cyclomedia Street View

The proposed charter change would allow the CPC to map R5D throughout the area within walking distance of the station (a small portion already has this designation). The housing production effects could be far greater than those possible even in the CPC-approved version of COYHO.

The charter proposal would also apply ELURP to several other categories of land-use actions considered minor.[25] In addition, a special version of ELURP, in which the city council would be the final decision-maker and the CPC would not be involved, is proposed for dispositions of property, and acquisitions of property for the purposes of disposition, to companies organized exclusively to develop housing for persons of low income. This creates the interesting possibility, should ballot proposals 1 and 2 be approved by voters, that the council would be involved in approving the disposition of city-owned property to an HDFC while the BSA would be charged with approving zoning waivers. In that event, the council might well want to weigh in on the zoning waivers as well, regardless of what the charter specifies.

Ballot Proposal 3: Establish an Affordable Housing Appeals Board

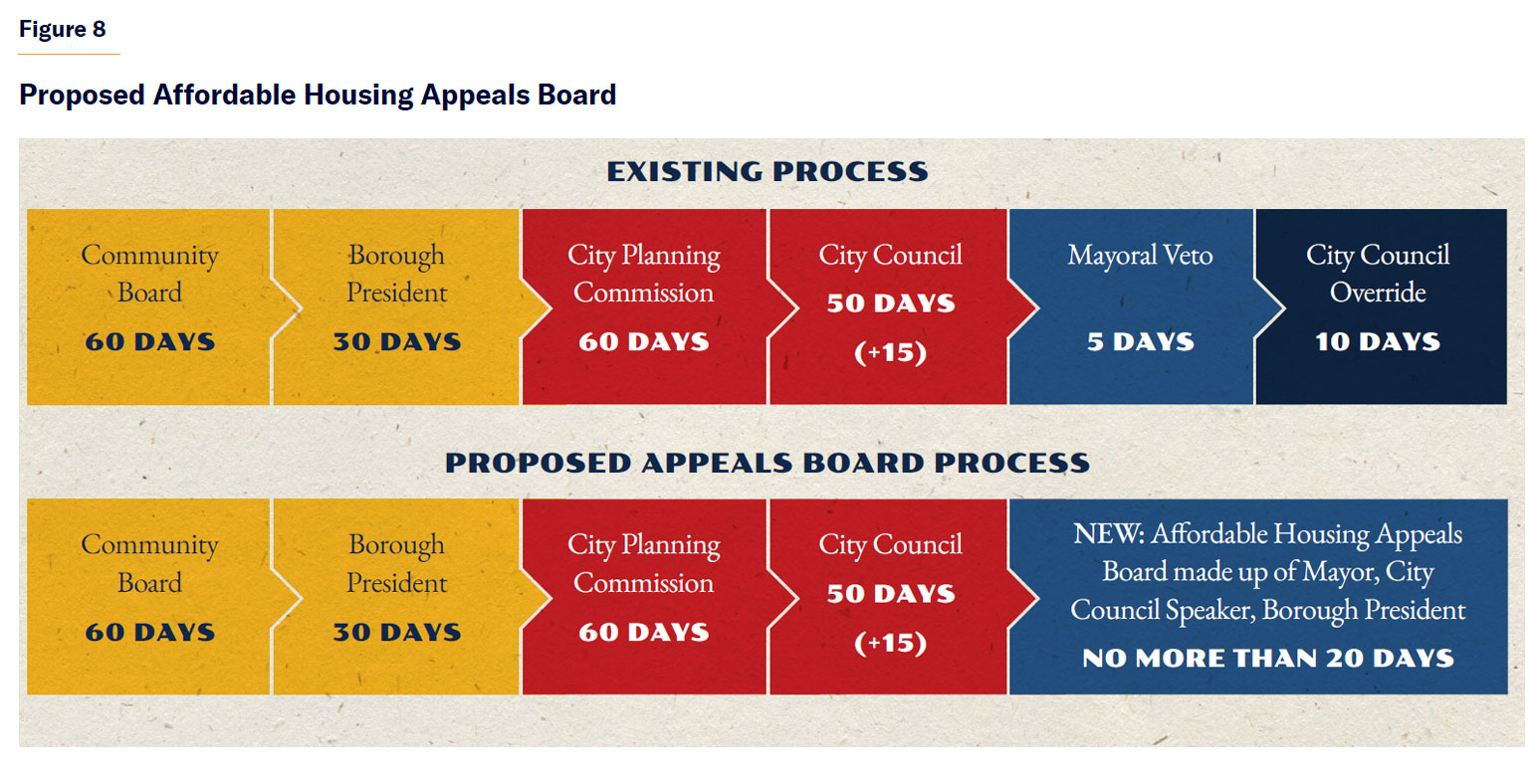

A third CRC land-use proposal[26] would establish an affordable housing appeals board to replace the current mayoral veto of specified city council actions. The mayoral veto has proved ineffective because of member deference; council votes are usually lopsided enough to override a mayoral veto, and thus the mayor chooses not to use the power in the face of certain defeat. The proposed change is summarized in Figure 8.

The appeals board would consist of the mayor, council speaker, and applicable borough president. The idea is derived from written testimony that I submitted to the CRC in March 2025,[27] although adapted to the CRC’s specific objectives. In the CRC proposal, the board’s jurisdiction would be activated when the council disapproves or modifies a land-use application approved by the CPC facilitating the development of affordable housing. Such an application can affect only a single borough—generally speaking, a site or an area of that borough. By the vote of two of the three members, the board could call up the application. Also by the vote of two of the three members, the board could reinstate, in whole or in part, the application as approved by the CPC. The board would not have the power to make new modifications.

The proposed board would have the most effect in situations where the mayor and borough president were aligned in opposition to a council member trying to defeat a land-use application facilitating new affordable housing, such as a rezoning in the member’s district. The possibility that the board might be activated would likely moderate the member’s position and make council approval more likely with modifications acceptable to the mayor. Less frequently, the mayor might align with a speaker trying to keep the council members in line.

An example of the type of situation where this provision might come into play is One45, a mixed-income project in Harlem whose rezoning application was withdrawn in 2022, facing certain defeat at the council due to the then–council member’s opposition.[28] With the election of a new, more conciliatory council member, the project was resurrected and approved by the council in 2025.[29] Had the appeals board been in place, and the project supported by the borough president or the council speaker, the community might already be benefiting from a completed project.

Commentators have noted that this proposed charter change re-empowers borough presidents, who largely became figureheads after the 1989 changes that abolished the board of estimate.[30] Some questioned whether the provision would simply allow the mayor to bypass the council member’s concerns and cut a deal with the borough president. My expectation, like that of the CRC, is that borough presidents will be responsive to local opponents, as the council member would be. However, the borough president, elected on a borough-wide basis, would be less fearful of electoral defeat based on hyper-local concerns. That increases the likelihood of an outcome that takes the city’s broader needs, particularly for housing production, into account.

Effectuating a Land-Use Revolution

The proposed charter amendments can be viewed as solving several long-standing political problems. One is the issue of scatter-site affordable housing, an outgrowth of the mandate in the 1968 Fair Housing Act that recipients of federal housing aid “affirmatively further fair housing (AFFH).” According to a summary of a proposed federal regulation published in 2023, “The Fair Housing Act not only prohibits discrimination, but also directs HUD to ensure that the agency and its program participants will proactively take meaningful actions to overcome patterns of segregation, promote fair housing choice, eliminate disparities in housing-related opportunities, and foster inclusive communities that are free from discrimination.”[31]

Housing policy experts understand this mandate as requiring that localities build a significant share of new affordable housing outside high-poverty and majority-minority areas. In the early post–Fair Housing Act period, the administration of Mayor John Lindsay took that mandate seriously, proposing new low-income housing in the majority-white and relatively affluent neighborhoods of Riverdale, the Bronx; and Forest Hills, Queens. The Riverdale project, known as Faraday Wood, was originally proposed for 340 units in an 18-story building, of which 20% of the units would be low-income. With development thwarted by community opposition, the site was sold to the Soviet Union, to become staff housing for what is now the Russian mission to the United Nations.[32] The Forest Hills project was ultimately scaled back and tenanted largely by whites, in a compromise with community opponents brokered by future New York governor Mario Cuomo.[33]

After these bruising battles in the early 1970s, NYC avoided controversial low-income housing proposals in affluent white-majority areas with strong political opposition. At the same time, the federal government showed little interest in implementing the Fair Housing Act mandate until a proposed AFFH rule was drafted by the Obama administration in 2015, and again by the Biden administration in 2023. Trump’s administration has subsequently withdrawn the Biden proposal and returned to the pre-2015 practice of not pressuring federal housing funding recipients to comply with an expansive interpretation of the AFFH mandate.[34]

NYC remains politically committed to AFFH principles,[35] and low-income households benefit from new affordable housing located in neighborhoods with better public services and access to employment centers. NYC has utilized inclusionary zoning mechanisms and tax incentives in recent years to achieve construction of mixed-income housing in medium- and high-density zoning districts, including middle- and high-income white-majority areas. However, new affordable housing construction has been sparse in recent years in some areas, such as Manhattan’s Upper East and Upper West Sides, as well as low-density zoning districts.[36]

The proposed charter changes would allow the mayor substantial leeway to secure approvals for affordable housing in these areas, despite opposition of the local council member. This is not merely an academic possibility; in the 2025 mayoral election, Zohran Mamdani, the Democratic candidate and the current polling favorite, built a primary-winning coalition of renters and residents of relatively high-density areas where new housing development has been concentrated in the past two decades. Andrew Cuomo, his leading primary opponent and now running in the general election as an independent, found a significant part of his smaller coalition in many low-housing-production areas likely to be on the initial list of the 12 community districts designated for ELURP.[37]

Should Mamdani win the November election, and the charter changes be approved, he would have enhanced power to overcome local opposition to new housing in areas where, in doing so, he would likely alienate relatively few of his supporters. The mayor’s power under the changed charter is not absolute; he will still need the city council’s support—not only on land-use issues still subject to ULURP but on the budget and other matters under the council’s purview. Many affordable housing developments will continue to require council approval for city-owned land dispositions and tax exemptions. However, it is possible, should the charter changes pass, that the ideals of the Fair Housing Act, enacted following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King but not seriously pursued after initial community pushback, will finally be realized in NYC—to a far greater extent than has been seen anywhere else in the nation.

Ballot Proposal 2’s provision that shortens the approval timeline for rezonings in low-density areas applies not only to affordable but also to fully market-rate housing. This is an important observation because many past mayors have formed a successful electoral coalition that unites affluent Manhattanites and antidevelopment homeowners in low-density areas of the other boroughs. That led to widespread “downzoning” of low-density areas in the mayoral administrations of Edward Koch, Rudolph Giuliani, and Michael Bloomberg. The proposed fast-track rezoning process would allow the CPC to reverse that pattern and even increase permitted residential densities beyond the starting point of the 1961 zoning[38]—again, even over the objections of the local city council members.

As I observed for COYHO,[39] and continuing with the proposed Ballot Proposal 2 change, satisfying housing demand while preserving an ideological commitment to the MIH program in medium- and high-density areas drives NYC’s housing planning into dependency on the areas with the least transit access and the highest levels of auto ownership. NYC would be much better off if the city simply made new unsubsidized apartment building construction possible in the maximum possible number of medium- and high-density areas. That could focus new housing on areas that are generally well served by public transit, have lower car ownership per household, and are relatively close to the employment concentrations in the city’s central business districts.[40]

MIH’s affordability mandates represent a de facto tax on new housing in rezoned medium- and high-density zoning districts. These mandates ensure that new housing is economically feasible only to the extent that it is offset by explicit public subsidies or property-tax exemptions, which provide private developers with an acceptable return on investment. Since the city’s ability to supply cash subsidies is limited by available resources, that in turn makes potential private MIH developers dependent on the state legislature, which sets the terms of the tax exemptions.

The tax exemptions are most valuable to developers in the city’s highest-rent areas. Thus the city also becomes dependent on continued high market rents to make the MIH program economically feasible, even with the property-tax exemption. I wrote in 2020 about how the city’s own study indicated that MIH could work only in neighborhoods with the strongest underlying rental housing markets.[41] Sadly, the map of areas where the MIH program is economically feasible has likely expanded since then, but only because the city’s ongoing housing supply crisis has caused market rents to escalate. Because rents need to be so high to make MIH work, any zoning initiative in medium- and high-density zoning districts is self-limiting in terms of spurring housing production.

The most recent version of the tax exemption, known as 485-x, applies prevailing-wage requirements to buildings of 100 units or more. These requirements are likely infeasible in most of the city, further limiting potential MIH housing production to buildings of 99 units or fewer.[42]

I discussed some of the needed MIH reforms in a 2023 report.[43] The key is to create predictable, easy-to-obtain waivers of MIH requirements in cases where those requirements cannot feasibly be met. Those reforms would require the support of both the next-term mayor and the incoming city council, which, even after the CRC-proposed charter changes, still gets to vote on amendments to the text of the city’s Zoning Resolution.

In the absence of such enlightened pro-housing reforms, the Ballot Proposal 2 charter proposal for low-density zoning districts allows the CPC to designate areas for construction of small market-rate condominium and rental buildings, unconstrained by affordability mandates or state tax-exemption programs. Mapping R5D over blocks of small homes in high-demand neighborhoods could allow for a meaningful housing increment quickly, as homeowners cash in on their homes’ value as development sites for small apartment buildings.

That might seem just fine to housing-hungry New York households, but building large amounts of new housing beyond easy walking distance of the subway and neighborhood services has predictable effects: high car ownership, overuse of on-site open space and available curbside space for parking, and excessive auto commuting at peak times when the arterial highway system is already at capacity. Although COYHO largely retained off-street parking requirements for new housing in low-density neighborhoods, the number of cars generated by new housing will exceed required spaces where car ownership exceeds one per household. This is often the case in areas where public transit use is low. On-street parking often proves inadequate in these areas.

Some of these impacts can be mitigated by transit improvements—particularly, improved bus service feeding from low-density areas into the subway and commuter rail. Two recent reports have criticized the slow pace of the city’s rollout of global-standard bus rapid transit.[44] While taking road space away from autos has historically been a heavy political lift, this charter amendment makes it a planning imperative.

Another important zoning amendment that NYC should undertake in the next administration is to eliminate off-street parking requirements for businesses, so that more space for retailers and other neighborhood services can be provided. Commercial space parking requirements are generally a bad idea because property owners know better than city planners how much parking they need. The city’s low-density areas include many shopping centers with large parking lots; zoning now requires that they be maintained. As these neighborhoods become denser, services need to increase as well, which may create a demand for more commercial space that could be met by building in what are now required parking lots. Allowing more commercial construction will deter excessive driving and improve residents’ quality of life.

The affordable housing appeals board established by Ballot Proposal 3 would mainly affect proposed rezonings in the 47 community districts not on the low-affordable-housing-production list. In those community districts, the appeals board could be activated in the face of council-member opposition to proposed rezonings to medium- and high-density districts, including areas where new housing is currently not allowed. Those rezonings, if this charter change is enacted, will be more likely to get to some version of “yes,” albeit with modifications that respond to community objections, than in the past era of pure “member deference,” when several well-publicized zoning changes, like One45, were simply defeated. This version of give-and-take between representatives of the local and the citywide interest is much closer to the way ULURP worked from 1975 to 1990, when the board of estimate was the final land-use decision-maker, as well as the early years of city council control after 1990, when the council was dominated by strong speakers. That, in turn, will encourage more applicants to enter the public review process to seek rezonings. However, since MIH is still a prerequisite of such rezonings, economic feasibility will remain a constraint.

Conclusion

In my view, the city will be better off with the approval of these three ballot proposals amending the city charter’s land-use provisions. The housing supply crisis demands innovative solutions. With these changes, the zoning map will be more permissive, and thus more housing will be built. The city council will still have avenues to influence land-use decision-making, even where it no longer has the final vote. Mayors will need to negotiate with local opponents and make concessions. However, in many cases, opponents will no longer have a blocking veto, through the local council member, to new housing.

I recognize that this optimistic scenario must be tested by experience. The CPC and BSA should use their new powers responsibly and be sensitive to the potential for bona fide land-use impacts from rezonings.[45] The success of these changes also depends on good-faith efforts in medium- and high-density areas to make MIH less of a deterrent to new housing construction. This would allow more housing in areas well served by transit. In areas beyond walking distance of rail transit, mostly low-density, NYC needs to adopt international best-practice bus improvements and zoning regulations less oriented to maximizing car trips. These would permit New Yorkers living in areas long since adapted to the auto-oriented lifestyle to travel more via public transit and meet more of their needs locally instead.

If the city proves unable to implement such efforts, a public backlash against the charter changes would be likely. That could result in the reinstatement of city council oversight and empowerment of development opponents in a city with continuing housing supply shortfalls.

Through these proposed charter changes, NYC gets another chance to reinvigorate its growth in a sustainable way. Seizing that opportunity well is an enormous challenge for NYC’s government.

Endnotes

Photo: Stocktrek Images / Stocktrek Images via Getty Images

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).