Looking to get the most from your Dispatch experience? By filling out a few key details about yourself, you can help us ensure we’re delivering exactly the kind of content you want to read. We’re all about prioritizing your time and interests—fill out this quick survey to get started.

Dear Reader (including those of you who don’t put the lime in the coconut),

In the TV series Yellowstone, one of the most poignant and heavy-handed themes is that the “cowboy” is dying out. Every now and then, one of the cowboys will lament that there are so few of us real cowboys left, and in 10 years, it’ll be impossible to work as a cowboy in America because we’ll get all of our beef from Brazil.

Now, this isn’t true, strictly speaking. The beef industry is contracting for a bunch of reasons, but it’s nowhere near collapse (more on that in a moment), and trade with Brazil is probably not in the top five reasons. Also, it’s worth pointing out that even during the glory days of the cowboy, very few Americans were cowboys—between 30,000 and 40,000 (and a big chunk of them were black and Hispanic, for what it’s worth). That means that at their peak after the Civil War, using very generous definitions of “cowboy”—like cattle hands, etc.—maybe 0.2 percent of the labor force could come close to calling themselves bona fide cowboys.

But the lament feels true-ish, because nostalgia, while often glaringly wrong on the facts, speaks to some very real feelings about change, progress, etc. Yellowstone’s appeal derives in part from its sometimes deft, sometimes cartoonish appeals to cultural unease or even panic about the decline of “masculinity.” A bigger source of its appeal is its sometimes deft, sometimes cartoonish use of sex and violence. But that’s hardly anything new.

The American experiment is still happening.

As the United States approaches its semiquincentennial, The Dispatch has launched The Next 250—a year-long project examining America’s founding principles and what makes this country, imperfect though it may be, so exceptional. Featuring exclusive essays from historians, political theorists, military experts, legal scholars, and cultural commentators, we’re exploring the biggest questions facing our nation and the unique qualities of this big, messy experiment we call home.

Then again, neither are appeals to nostalgia and ideas about masculinity. The Western has always been popular. But I think it’s fair to say the genre’s high-water mark was the two decades after World War II. In 1959 alone, there were 30 Western-themed shows in primetime (at least according to Wikipedia). John Wayne made around 180 movies, and around 80 of them were Westerns.

The appeal of the Western is inseparable from American masculinity and nostalgia for the “real America” that most Americans never actually lived in. Those aren’t the only reasons for the genre’s popularity, of course. The conquest of the frontier, the struggle between the law and the lawless, rugged individualism, and similar themes are deeply ingrained in American culture because they’re deeply ingrained in American history.

One irony about Westerns is that, despite being one of the most identifiable and quintessentially American pop cultural products, a lot of them are pretty anti-capitalist. The villains are often bankers (Stagecoach), or railroad tycoons (Once Upon a Time in the West), or cattle barons (Shane). In Bonanza, the villains were routinely cattle barons, bankers, railroad magnates, mining companies, etc. Sometimes, the anti-capitalism is more nuanced: for example, big business rolling over the small entrepreneur. Deadwood is one of the best examples of this. But McCabe & Mrs. Miller is a more fun and transgressive example: An enterprising businessman starts a brothel and casino, but then a mining conglomerate comes in and wants to put them out of business.

One could also note that the Western’s relationship with traditional values and Christian morality is much more complex than one might expect, given their stereotypical target audience. I mean, there are more prostitutes in Westerns than at Matt Gaetz’s bachelor party. But that’s a different rabbit hole.

Some of the nostalgia or male insecurities that some Westerns tap into is bound up with the notion that “progress”—that is, capitalist-driven progress—gets in the way of real men having a good time. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence (easily one of my favorite movies), is partly about how “progress”—i.e. the rule of law—throws a wet blanket on the very masculine free-for-all of the Wild West.

So what’s the point of all this?

Well, simply that a lot of the stuff that happens in America that the right doesn’t like is driven by a thing the right professes to like a great deal: Capitalism.

Capitalism, not wokeness or lefty social engineering, is the single most powerful engine of social transformation ever invented. I’ll spare you a few thousand words on Joseph Schumpeter and just make things more concrete. I love print newspapers and magazines. They’re dying—or dead—because of technological innovation in pursuit of profit. The general store was killed by department stores, grocery chains, and other big retailers. It’s largely forgotten now, but the decline of the general store—which was often the primary source of debt financing for farmers and rural Americans—was one of the biggest drivers of populism in America and Europe in the 1930s. One of the promises in the Nazi Party’s 1920 platform was the “communalizing of big department stores.”

“Where is the corner groceryman?” Huey Long raged in the early 1930s. “He is gone or going. … [The] little independent businesses operated by middle-class people … have been fading out … as the concentration of wealth grows like a snowball. In other words, the middle class is no more.”

That wasn’t remotely true, or at least not for long. The middle class grew massively after World War II. But it was true that for a time, the most common route to the middle class and economic self-sufficiency was, at one point, opening your own store. The big chains changed that. It made it harder to become your own boss, which was seen as part of the American dream. The crowding out of the mom-and-pops seemed to close off a path to realizing that dream. In the words of Robert and Helen Lynd in their landmark 1937 work Middletown in Transition, this crowding, combined with the Great Depression, “increased this helpless commitment of a growing share of the population to the state of working for others with a diminished chance to ‘get ahead.’”

What’s remarkable is how often Americans lament changes in the status quo, only to lament the end of the same status quo. The introduction of factories invited massive pushback and lamentations from intellectuals and citizens alike, across the ideological spectrum. And the closure of factories arouses similar rage today. Some intellectuals are pretty funny about this. As I’ve noted before, Patrick Deneen regrets the turn we took in opening factories at the beginning of the industrial revolution in the 18th century and laments the closing of factories in the 21st.

I bring all of this up to provide some broader context to a particularly stupid controversy about Cracker Barrel. The company was launched in 1969 by a Shell Oil representative as a kitschy gas station eatery and Southern tchotchke joint. Fill up on some chicken-fried steak after you fill the tank, and maybe pick up a fun apron for Grandma that says, “Kiss My Grits.” It became successful, expanded, left the gas stations behind, and eventually went public.

I have no beef against Cracker Barrel. I’ve eaten in a few. The food was not stellar, but it was better than you might expect, and the service was good. The funny thing about Cracker Barrels is that they’re little capitalist temples to faux authenticity. This is not some grand institution with deep cultural roots in the South, or any place else. Cracker Barrels in New York sell Reuben sandwiches, and Cracker Barrels in Texas serve salsa.

You know why? To make money. And consumers in Texas apparently want salsa, and customers in New York want Reubens. Indeed, as it expanded outside of the South, the decorations changed to fit the locales, too. It has an industrial-scale décor warehouse to provide “local flavor” to each restaurant.

Now, Cracker Barrel is updating its décor and branding—slightly. The bulk of the update is a brighter, less cluttered interior design, but the “controversial” decision is to change its logo. The company removed the old white guy in overalls sitting by a barrel, and now just has a text-only sign that reads “Cracker Barrel.”

And people are losing their minds, claiming that it has gone “woke.” What seems to have sparked this brouhaha is a tweet saying that the store has “scrapped a beloved American aesthetic and replaced it with sterile, soulless branding.”

This prompted an outraged “WTF is wrong with @CrackerBarrel??!” tweet from Donald Trump Jr., that loyal guardian of all that is homey and traditional in American life. The very popular End Wokeness Twitter account proclaimed: “Cracker Barrel CEO Julie Masino should face charges for this crime against humanity.”

Chris Rufo then came out with a Cracker Barrel delenda Est pronunciamiento:

Alright, I’m hearing chatter from behind the scenes about the Cracker Barrel campaign and, on second thought: we must break the Barrel. It’s not about this particular restaurant chain—who cares—but about creating massive pressure against companies that are considering any move that might appear to be “wokification.” The implicit promise: Go woke, watch your stock price drop 20 percent, which is exactly what is happening now. I was wrong. The Barrel must be broken.

Now, it’s true that Cracker Barrel has done some LGBT marketing stuff, probably as a result of being criticized for alleged discriminatory policies in the 1990s. But maybe also because gay people—and people who aren’t particularly horrified by gay people—might like good, affordable breakfasts, too. They’ve also tried to cultivate Hispanic customers. I’m not sure this means they’ve been taken over by the Latinx reconquista.

I am also, shall we say, skeptical that a few old website screenshots of these efforts are proof that, in the words of Federalist co-founder Sean Davis, “Cracker Barrel’s CEO and leadership clearly hate the company’s customers and see their mission as re-educating them with the principles of gay race communism.”

Oh, one last thing about all of these lovers of American heritage and culture—since, uh, 1969—Cracker Barrel’s new logo is … wait for it … the original logo.

Cracker Barrel’s core customer base is what demographers and marketing gurus call “old.” Lots of chain restaurants change things up to deal with the fact that old people have a high propensity to die in the near future, while young people have more prospective CLV (customer lifetime value). This is why McDonald’s sells more salads and snack wraps these days.

Many businesses and products are incapable of updating to new market demands, so they die. You know why no one drinks Tang anymore? I mean, aside from it being meh. The Baby Boomers stopped drinking the NASA-inspired elixir, and younger generations never touched it. Jell-O will never recover its glory days, because tastes change and chunks of fruit in aspic-like globules are gross. Ovaltine went the way of the Dodo when the generation raised on it died out. Ditto the once wildly popular Postum, which I’d bet most readers of this “news”letter have never even heard of. (Editor’s Note: This 25-year-old editor had to Google it.) When was the last time you had a burger at Howard Johnson’s? I loved that place as a kid.

So Cracker Barrel is trying to fend off similar forces of economic entropy. Maybe it’s a bad idea. Maybe not. But heaven forbid anyone blame capitalism, not when the bogeyman of wokeness is available. But the anti-woke warriors are happy to use capitalism—in precisely the way they decry when the left does it—to badger them for failure to comply with their ideological and aesthetic demands. Cracker Barrel lost 11 percent of its market value because of this idiocy.

Back to capitalism and social change.

The social and cultural change wrought by capitalism-fueled innovation is behind a lot of the things people—including, in some cases, me—don’t like about American culture. Social media is the most obvious example, but not the most important one.

Some of the “1950s” jobs that the new right wants back have been lost to trade, but far more have been lost to robots. But who often gets the lion’s share of the blame? Immigrants. But blaming immigrants isn’t good enough. If you can’t ultimately pin the charge on Democrats and other peddlers of “gay race communism,” what’s the point? So Democrats or “the left” get blamed for letting the immigrants in to “replace” the workers who think the Cracker Barrel logo guy was their grandfather. They’re the ones who won’t let us be cowboys anymore.

For years, I’ve tried to make the case that the left doesn’t appreciate how much social progress can be credited to free markets. They always want to tell a story of how every good thing has come thanks to enlightened and heroic government policies over the objections of racist, sexist, or otherwise bigoted and reactionary greedy capitalists. Sometimes government policies were necessary and good, to be sure. But sometimes government policy stood in the way of progress.

You know who hated the “back of the bus” segregation policies of the Jim Crow South? The for-profit bus companies. Under Jim Crow, segregation was right-wing wokeness. What I mean is that the established political powers imposed ideological priorities on free people and free enterprise. As Thomas Sowell has recounted, mass transit businesses lobbied against segregation because it was an undue regulatory burden. Capitalism, you see, is more often than not on the side of freedom. And freedom begets change.

In 1953, the owner of Anheuser-Busch, “Gussie” Busch Jr., bought the St. Louis Cardinals. He was miffed that the Brooklyn Dodgers were mopping up thanks to their acquisition of Jackie Robinson, the first black Major League Baseball player. He asked his staff how many black players the Cardinals had in the pipeline. They said none. “But,” he stammered, “we sell beer to everyone!”

We now live in a moment when many on the right don’t like the churn of capitalism and creative destruction. They want their say about what Robert Nozick described as the practice of “capitalist acts between consenting adults.” They want to score corporations for their “social responsibility”—as they define it—every bit as much as the left did, and does. Milton Friedman spent years taking flak from the left for saying that corporations’ only responsibility is to maximize returns to shareholders (within the law). If he were around today, he’d be taking even worse flak from the right for his willingness to surrender to gay race communism.

And that would be before he even ventured an opinion on the federal government’s new acquisition of Intel.

Various & Sundry

Canine and Feline Update: Everyone has been doing well, though Pippa’s appetite has been off. We have no idea why, and I have told her it’s unacceptable. It’s impossible to tell, however, if she actually feels bad, given her spanielly addiction to slumber and belly rubs and her tendency to liven up once outside. Gracie, too, likes her sleep. Only Zoë greets every day with the spirit of carpe squirrel. I’ve gotten a massive new tranche of Fafoon and Paddington content. For those of you who don’t recall, they were my late mother’s cats and now live full-time with my mom’s dear friend Dru. All you need to know is that Fafoon was apparently exiled from a parallel dimension where she ruled the known universe and is constantly annoyed that the rest of us didn’t get the memo. Paddington, meanwhile, is one of the softest cats on earth, and thinks he’s a dog. He’s also crazy. Oh, and Chester continues to shake us down.

I will be on CNN’s State of the Union on Sunday.

I recorded a marathon episode of Adaam’s podcast, Uncertain Things. We covered a lot of territory. The episode should drop tomorrow.

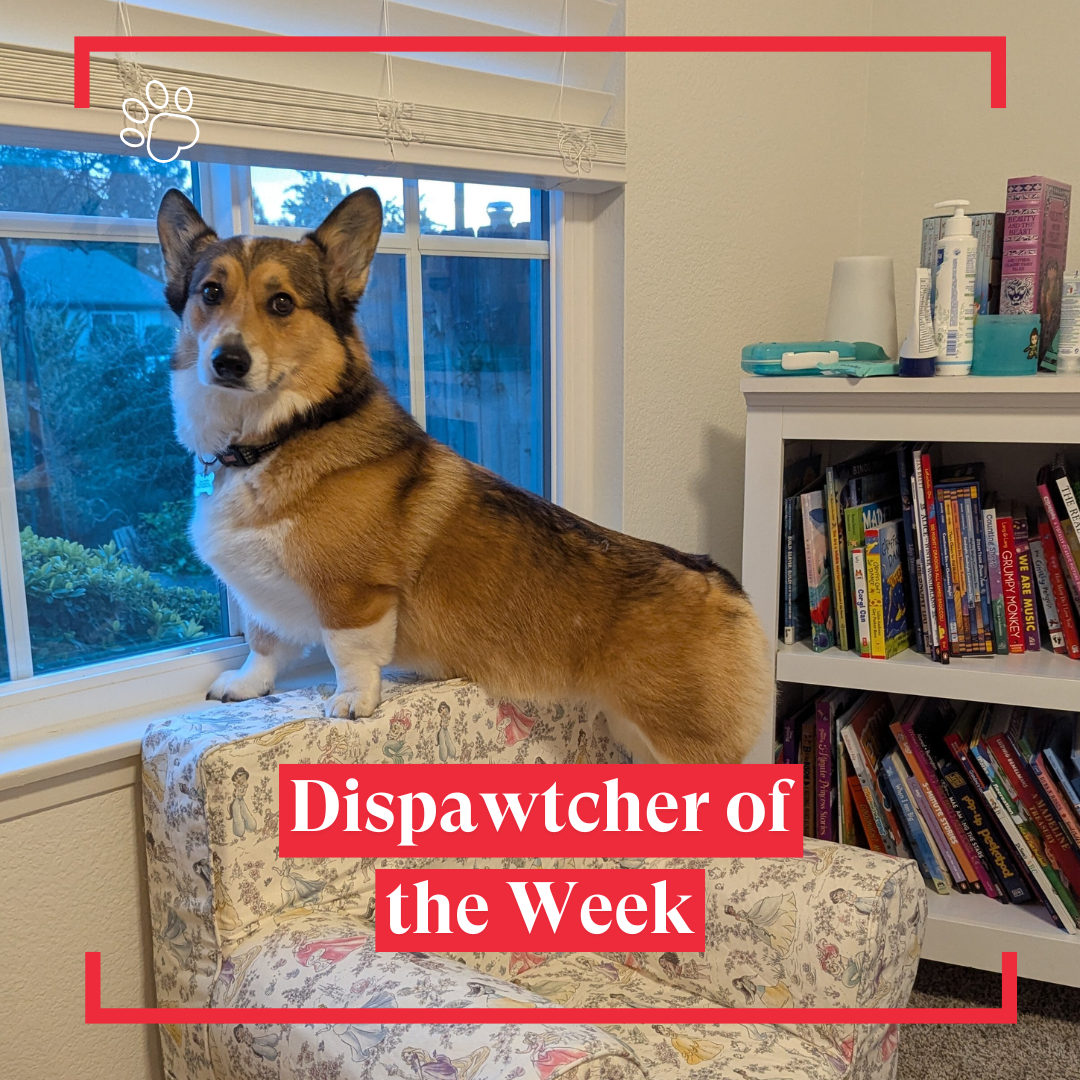

The Dispawtch

Owner’s Name: Marisa Gonzalez Martino

Why I’m a Dispatch Member: I’ve been a fan of Jonah’s since Liberal Fascism (I got scolded for reading it in high school English class because of the Hitler mustache on the smiley face). I don’t remember how I came across The Remnant podcast, but I was immediately hooked. I’ve been a Dispatch subscriber since day one. I appreciate the range of perspectives, the in-depth reporting, the fact-checks, and most especially the podcasts.

Pet’s Name: Basil (rhymes with dazzle)

Pet’s Breed: Welsh Corgi

Gotcha Story: In late 2019, after two unsuccessful pregnancies and desperate for something small and noisy to love, my husband and I got Basil.

Pet’s Likes: Basil loves belly scritches and treat-os, playing tug, fetch, and chase.

Pet’s Dislikes: Basil’s true nemesis is the doorbell, but he also regularly does battle with any bird that lands in our backyard.

Pet’s Proudest Moment: After four years of tolerating his human sister only when she dropped food, Basil recently trained her to play fetch and tug correctly. He’s very proud.

Bad Pet: He puked up the remains of a toy squeaker on the carpet about 20 minutes ago.

Do you have a quadruped you’d like to nominate for Dispawtcher of the Week and catapult to stardom? Let us know about your pet by clicking here. Reminder: You must be a Dispatch member to participate.

Weird Links

No weird links today. My apologies.