I like alternative-timeline movies for their funny little details, like that scene in Watchmen when two former superheroes are reminiscing about how their lives were derailed by Richard Nixon, still president and essentially a dictator in this imaginary version of the 1980s. “To think, I voted for that prick five times,” says the grizzled old veteran. His younger interlocutor shrugs: “Hey, it was him or the commies, right?”

We live on the dumbest timeline. I know this because millions of Americans believed that they had to vote for Donald Trump to avert a national descent into socialism—“It was him or the commies, right?”—and so they sent the malignant little criminal back to the White House, where he went about . . . setting up state-owned enterprises in order to seize the means of production on behalf of the workers. It’s still more Idiocracy than Watchmen or 1984, but it’s all in the mix. If it were a series of shorts, it would be called Way More Than Three Stooges.

“Don’t get so excited,” the apologists say. “This is basically like the financial crisis, with the bailouts and General Motors.”

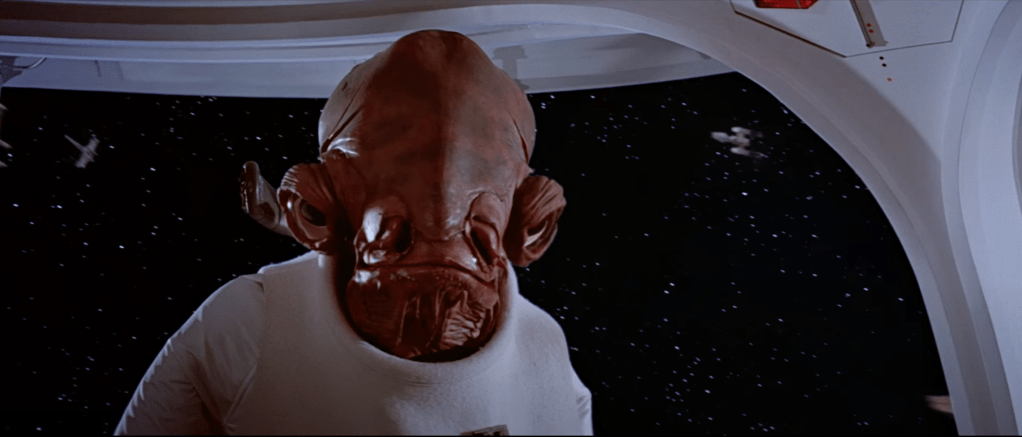

Oh, is that it? In the words of CFO Gial Ackbar: “IT’S A TARP!”

You’ll remember TARP–the Troubled Asset Relief Program—and the bailouts that were executed during the 2008-09 financial crisis. I don’t think anybody remembers that time fondly except for me and other journalists who had the daily pleasure of writing about it. Bad times, great story.

I suppose there are some similarities between the Trump administration’s partial nationalization of Intel and the Obama administration’s bailout of GM, in which the U.S. government owned an equity stake. You have two opportunistic presidents who like to talk about economic nationalism jumping into two businesses they don’t understand for purely political reasons and, in both cases, probably doing so illegally. The U.S. government ended up losing billions of dollars on its “investment” in GM, and there is every reason to believe that Uncle Stupid’s stake in Intel—whose Ohio-based chip-foundry is foundering because it has no customers—will end in tears one way or another.

Citing the bailout policies of the early 21st century as your model going forward is a real . . . interesting choice. U.S. taxpayers lost billions on GM, and GM is still a piss-poor company that makes inferior products at every price point from $20,500 to $130,000-and-up while pissing away billions of dollars on mismanaged overseas partnerships. It didn’t even make sense from the political baloney “saving jobs” point of view, inasmuch as GM has shed some 80,000 employees since 2008. The heavy-handed government-backed GM restructuring saw the firm kill off Saturn as a sop to the union bosses, who did not like the semi-autonomous division’s independence from rigid work rules. The parallel bailout of Chrysler (not Chrysler’s first) saw the administration essentially rob the bondholders—the secured creditors who had first claim on the firm’s assets—to pay off its union-goon allies.

The bank bailouts were no better. The geniuses in Washington who fretted that firms such as JP Morgan were “too big to fail” watched, apparently helpless, as those firms grew larger and larger during subsequent years of consolidation—JPM today has a market value four times what it was back when we were all hearing the words “systemic risk” five times a day.

The economics of failing banks can be pretty funny, in a so-obvious-you’d-think-somebody-would-notice kind of way: When a badly run bank gets bailed out by the badly run government, the market concludes—correctly—that the badly run bank has the badly run government’s backing, and access to the badly run government’s magical money machine. That means that the badly run bank can access capital at a lower cost than its better-run competitors, and it uses that cheap money to buy up those better-run competitors and various little fish, creating a much bigger badly run bank. Financial systems dominated by a relatively small number of large banks rather than by lots of smaller players in a large competitive marketplace tend to be more brittle, experiencing worse outcomes during economic crises.

The bank and nonbank bailouts of the TARP era were different from what Trump is doing in many important ways: The GM shenanigans probably were illegal, but the overall bailout program was, for good or for ill, duly authorized by Congress (it was the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008) and other relevant authorities, and the program was kept on a reasonably short leash—and by the very modest criterion of having prevented a total worldwide credit collapse, you might even call it a short-term success. We are not in a comparable crisis now. And Trump, being Trump, is pretty vague about the legal authorization for his moves at Intel and elsewhere. The CHIPS Act gives the government the power to make grants to chipmakers (i.e., to engage in massive corporate welfare) but no explicit power to use those grants to buy stock in firms. As with the “golden share” that gives the U.S. government the power to veto decisions at U.S. Steel (now a subsidiary of Nippon Steel), setting the government up as a boardroom dictator is the whole point of the exercise. It is an open-ended project.

You can call that corporatism if the right-wing flavor of the word makes you feel better, but it is simply a half measure of socialism, a government takeover of certain economic assets for the purpose of replacing market forces with political mandates.

Hey, it was him or the commies, right?