“THE ALAMO HAS FALLEN!”

In March 1836, that tocsin spread terror throughout the fledgling Texas Republic. The timing couldn’t have been worse. On the second day of that month, while Antonio López de Santa Anna’s cannon hammered the walls of the mission fort, rebel delegates declared independence from Mexico; four days later, the caudillo launched an assault and killed every Texian (as Anglo-American colonists of Texas styled themselves) defender.

The Alamo garrison, commanded by Lt. Col. William Barret Travis, had overwhelmingly supported separation from Mexico. On March 3, Travis wrote his friend Jesse Grimes explaining why he and his men were risking their lives.

Let the Convention go on and make a declaration of independence, and we will then understand and the world will understand, what we are fighting for. If independence is not declared, I shall lay down my arms, and so will the men under my command. But under the flag of independence, we are ready to peril our lives a hundred times a day, and to drive away the monster who is fighting us under a blood-red flag, threatening to murder all prisoners and make Texas a waste desert.

Travis knew his history. Thomas Jefferson’s words and legacy weighed heavily. Independence: It evoked the power of heritage. It made Travis and his followers not mere adventurers, but soldiers in a righteous cause. He was unaware that delegates had already done the deed. Alamo defenders never knew, but they would have rejoiced at the news. A republic—now that was something worth dying for.

In the immediate aftermath, word of the calamitous defeat incited nothing but abject terror among Tejano (Texas residents of Spanish/Mexican heritage) and Irish settlers. Begun in mid-January in South Texas, the exodus of civilians fleeing Santa Anna’s army gathered speed following the loss of what was known as San Antonio de Béxar. Texians abandoned their homes, took to the roads, and headed east for the Sabine River or Galveston Island in what they, with mocking self-deprecation, labeled the “Runaway Scrape.” Virginia land agent William Fairfax Gray described the bedlam: “The Alamo has now fallen, and the state of the country is becoming every day more and more gloomy.”

Yet, in the weeks that followed, the Alamo dead became a source of pride and exultation. Contemporary newspapers extolled the departed defenders as “founders of new action as patterns of imitation!” David G. Burnet, the Republic’s interim president, reflected the mood:

The Alamo has fallen … Let us therefore, fellow citizens, take courage from this glorious disaster; and while the smoke from the funeral pyre of our bleeding, burning brothers ascends to Heaven, let us implore the aid of an incensed God who abhors iniquity, who ruleth in righteousness and will avenge the oppressed.

Their sacrifice delivered a potent rallying symbol—one that, seven weeks later, bore fruit on the boggy field of San Jacinto, near present-day Houston. There, Texian volunteers won a battle and the war—all the while howling their battle cry: “Remember the Alamo!”

The story continued to evolve and inspire. In 1840, Presbyterian minister A.B. Lawrence visited San Antonio. The Alamo had already become a tourist attraction, and it awed the pastor. He inquired rhetorically (and with considerable grandiosity):

Will not in future days Bexar be classic ground? Is it not by victory and the blood of heroes, consecrated to liberty, and sacred to the fame of patriots who there reposes upon the very ground they defended with their last breath and last drop of generous blood? Will Texians ever forget them? Or cease to prize the boon for which these patriots bled? Forbid it honor, virtue, patriotism. Let every Texian bosom be the monument sacred to their fame, and every Texian freeman be emulous of their virtues.

It’s no surprise Lawrence described the site as “sacred.” The Alamo became a central component of a secular religion. Consider the vernacular Texians employed. They celebrated William B. Travis, James Bowie, and David Crockett as the trinity of heroes; they eulogized the sacrifice of the defenders and the redemption of San Jacinto. The martyrs offered their lives in an abandoned mission, on consecrated ground as it were. Indeed, as if by divine design, they died on a Sunday.

After the Republic of Texas agreed to be annexed by the United States in 1845, Texans began to embellish the narrative. By the end of the 19th century, the parable became the central scene of a Lone Star State morality play, a melodrama in which slain champions served as elemental types. Consider the fevered prose of a popular 1888 textbook:

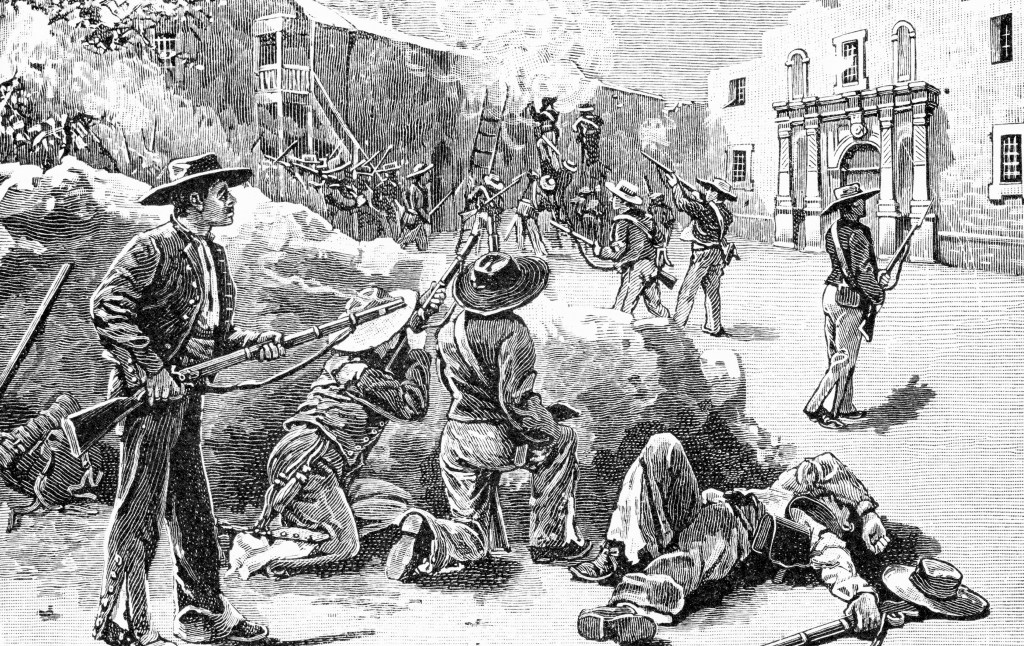

The Mexicans bleeding, wounded, and shattered, hesitated to renew the attack, but the stern command of Santa Anna and the flashing sabers of the cavalry, forced them on. By tens, by hundreds, they swarmed up the ladders. Down fell the first, down, down went the second, crushing all beneath them, while the Texans stood like gods waiting to let others feel their mighty strength.

Such assessments survived the 19th century and thrived even into the mid-20th century. In 1960, actor and director John Wayne styled his film The Alamo as “the story of 185 men joined together in an immortal pact to give their lives that the spark of freedom might blaze into a roaring flame. It is the story of how they died to the last man putting up an unbelievably gallant fight against an overwhelming enemy; and of the priceless legacy they left us,” according to a lobby display describing the movie.

Poor Duke. He unwittingly pinpointed the problem with the mythic version of the Alamo battle. The traditional story was, indeed, “unbelievably” gallant. On March 3, Travis wrote the delegates at the Independence Convention then assembled in the town of Washington-on-the-Brazos: “I look to the colonies alone for aid; unless it arrives soon, I shall have to fight the enemy on his own terms. I will, however, do the best I can under the circumstances.” Later that day, he revealed even more bitterness: “I am determined to perish in the defense of this place,” he explained, “and my bones shall reproach my country for her neglect.”

Travis was not, as some have insisted, a zealot with a death wish. Nor were his men bent on ritual suicide. Such fanaticism was not part of their cultural tradition. They were citizen soldiers. They may have been willing to die for their country, but that was never their intent. They fervently prayed that such a sacrifice would prove unnecessary.

It never occurred to them to join “in an immortal pact to give their lives.” (No reliable primary documentation supports the fable of Travis drawing a “line in the sand” asking those willing to die defending the mission fort to step across it.) That knowledge makes the Alamo defenders’ sacrifice more, not less heroic. When their political leaders did not respond to their repeated calls for reinforcements, Travis and his men did as they promised. They fought the enemy on “his own terms” and did the best they could “under the circumstances.” What more could anyone ask of them—or any soldier?

After the March 6 assault, Santa Anna entered the compound. Capt. Fernando Urissa observed him ambling among the smoldering corpses of both sides of the conflict. Surveying the dead, he betrayed no emotion whatsoever. “Urissa, these are the chickens,” he remarked. “Much blood has been shed, but the battle is over; it was but a small affair.”

Some have scorned Santa Anna for the callousness of his comment, but in pure military terms he was correct. Considering the scale of the Napoleonic wars and the 1810-21 Mexican Revolution, the 13-day siege appeared trifling indeed. By way of comparison, the Duke of Wellington suffered more casualties (some 5,365) at Talavera in 1809 than the total number of combatants at the Alamo. Therefore, one may forgive Santa Anna for believing the capture of an isolated border outpost to have been of marginal importance.

If that’s the case, why does the battle hold such sway in our collective imaginations? Why do we “Remember the Alamo”? Even before they rode into the old mission, James Bowie and David Crockett—he never encouraged anyone to call him “Davy”—were already frontier personalities. No matter where they occurred, the deaths of those celebrities would have attracted attention; it was especially poignant that they perished at the same time and place.

Myth is an unalienable part of the Alamo story. Even if it were possible, efforts to purge the mythic content would prove unwise.

Moreover, the Alamo was a last stand. Determined warriors standing against long odds and fighting to the last man has proven a fascination and inspiration to all nationalities (for an erudite examination of the topic, see Michael Walsh’s Last Stands: Why Men Fight When All Is Lost). Examples abound: the last stand of Leonidas and his 300 Spartans at Thermopylae, the last stand of the Jewish Sicarii at Masada, the last stand of Roland and his companions at Roncevaux Pass, the last stand of the Anglo-Saxon housecarls at Hastings, and the last stand of the Old Guard at Waterloo. Of course, Custer’s Last Stand in 1876, the most famous in American history, had not yet occurred when the Alamo fell in 1836.

Many still cling to the fiction that Alamo defenders died fighting to the last man. Several Mexican accounts confirm that soldados took captive six or seven defenders. Mexican Gen. Manuel Fernández Castrillón interceded with Santa Anna to spare their lives but “His Excellency” ordered their immediate deaths. Members of his staff drew their swords and hacked the unarmed prisoners into pieces. Best evidence asserts that Congressman Crockett was among these unfortunates.

No, the defenders did not fight to the last man. Rather, Santa Anna had his soldiers kill them to the last man. Therein lies a delicious irony. Had he been willing to take prisoners, he would have robbed the battle of its moral power; Americans would recall the Alamo only as a terrible debacle; Hollywood would have had no interest in making movies about a military disaster; and few today would express any curiosity in a long-forgotten defeat. Whatever mythic mojo the battle enjoys is because it was a last stand. And who was responsible for making it one? Antonio López de Santa Anna.

In recent years, activist historians and journalists have tried to “problematize” the accepted Alamo story in their attempts to “alter the narrative.” In their telling, the defenders did not die in defense of liberty and freedom, but to protect and promote the South’s “peculiar institution.” Fortunately, one can easily refute this pernicious poppycock.

The Alamo garrison was extremely cosmopolitan. It strains credulity to believe that James Brown of Pennsylvania, or John Flanders of Massachusetts, or John Hubbard Forsyth of New York, or Gregorio Esparza of Texas and especially Daniel Bourne from England, John McGregor from Scotland, Lewis Johnson from Wales, Stephen Denison from Ireland, Henry Courtman from Germany, or Charles Zanco from Denmark would have risked their lives for a “southern land grab.” Amos Pollard, chief surgeon of the Alamo garrison, was an ardent and vocal abolitionist. Further, Travis’ letter to the “People of Texas & all Americans in the world” made no mention of slavery. He explained his circumstance and implored his countrymen to come to his aid “in the name of Liberty, of Patriotism, & every thing dear to the American character.”

Slavery was part of the toxic stew that led to war—but never the main ingredient. The late Randolph B. Campbell, the foremost authority on Texas slavery, should have the final word: “The immediate cause of the conflict was the political instability of Mexico and the implications of Santa Anna’s centralist regime for Texas. Mexico forced the issue in 1835, not over slavery, but over customs duties and the general defiant attitude of Anglo-Americans in Texas.”

Myth is an unalienable part of the Alamo story. Even if it were possible, efforts to purge the mythic content would prove unwise. George Washington and the cherry tree and William B. Travis and the line in the sand are homilies that convey vital lessons. They are part of a shared national experience and constitute valuable cultural touchstones. It does children no harm to hear them and it may even do them some good. Ponder the wisdom of C.S. Lewis: “Since it is so likely that children will meet cruel enemies, let them at least have heard of brave knights and heroic courage. Otherwise, you are making their destiny not brighter but darker.”

Understand and appreciate myths; understand and appreciate history. But, please, graze them in different pastures. Hazards arise for both individuals and societies—not when they treasure national myths—but when they begin to mistake those myths for history. That said, when one strips away legend, what remains is still grandly heroic. Travis and his men personified the Spirit of ’76. Michael Walsh may have said it best: “They were not at the Alamo because they loved slavery or hated Mexicans but because they loved freedom and self-determination and were willing to die for it—archetypal revolutionary American traits still being evinced 60 years after the Revolution.” A yearning Americans termed “Manifest Destiny” may have steered A.B. Lawrence’s pen, but he was not wrong. At its core, the Alamo story is one of “honor, virtue, and patriotism.”