Well, they asked for a culture war, didn’t they? I’m thinking of the overzealous apostles of wokeness, who set out to trammel the right but ended up feeding the foul forces of Trumpism. As the comedian Marc Maron quips to fellow progressives in his new HBO special, Panicked, “You do realize we annoyed the average American into fascism, right?”

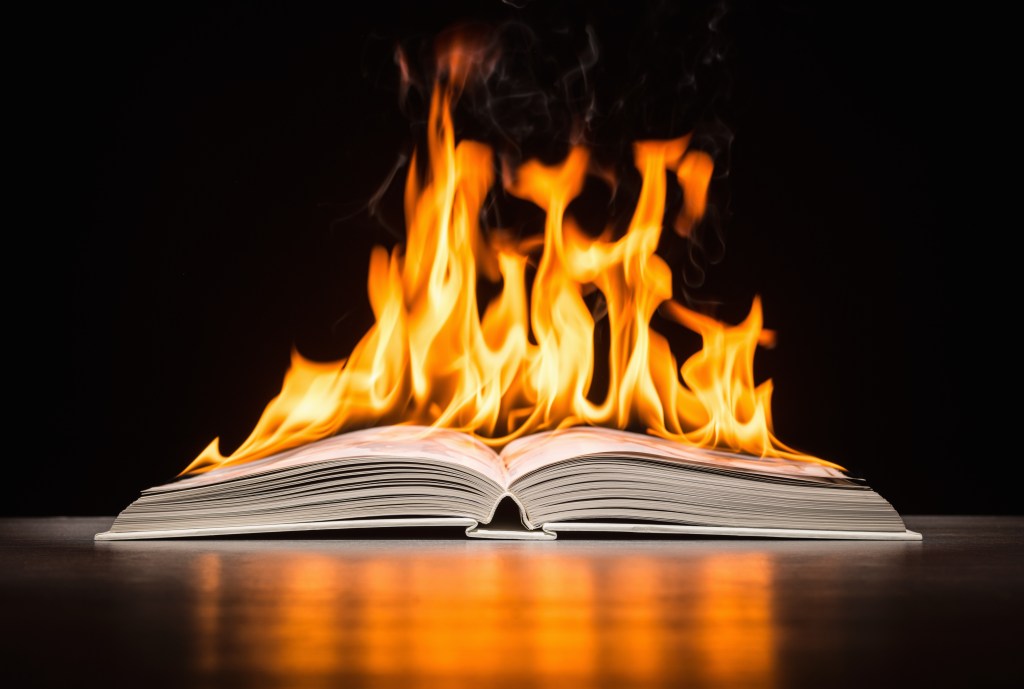

Another unintended consequence of wokeism—less often discussed but still gravely significant—is that it badly warped American literary culture. This is the argument that Adam Szetela puts across, with verve and erudition, in That Book Is Dangerous! How Moral Panic, Social Media, and the Culture Wars Are Remaking Publishing. It ought to be a galvanizing book, though I’d be surprised if it leaves many readers feeling optimistic. The degradation of our publishing ecosystem will be difficult to reverse.

Szetela, who recently earned his PhD in English at Cornell University, anatomizes what he calls the “Sensitivity Era,” which began crystallizing perhaps 15 years ago. It’s an era thick with ironies: Many online activists, who ostensibly wanted to broaden people’s horizons, went the opposite direction. They turned rigid, censorious, and exclusionary. Often, they weren’t very nice, either. Few currents in American intellectual life have been at once so ruthless and fragile.

You wouldn’t know it from its title, but much of That Book Is Dangerous! concerns young adult literature. To be fair, the genre was not without faults. Szetela shows that for a long time, it featured too few stories by LGBT authors and racial minorities, and occasionally trafficked in stereotypes. It seems likely that these problems were overlooked, at least partly, because the publishing industry has historically been overwhelmingly white.

Trouble arose in the Sensitivity Era, however, when legitimate calls for reform morphed into a moral panic. Take, for instance, the 2019 Twitter pile-on that occurred after Random House announced its plan to publish Amélie Wen Zhao’s debut novel, Blood Heir, which was set in a mythical kingdom where systems of oppression were not race-based. This provoked a swarm of digital detractors. They called Zhao “antiblack” and said she trafficked in “cultural appropriation.” Some of Zhao’s critics had read advance copies of the book, but thousands who amplified their complaints with shares and retweets had not—because it hadn’t been published. Sounding a bit like she had been kidnapped, Zhao swiftly offered an apology for the “pain” she’d supposedly caused.

Fortunately, Blood Heir eventually saw publication—and was generally well-received—but only after it was sent to “sensitivity readers.” As Szetela explains, many such readers are well-compensated but dubiously qualified. They may present themselves as “experts” simply by virtue of sharing identities with fictional characters. Often they give the poor impression that they think people from underrepresented groups all think and act alike.

There used to be an unwritten rule, Szetela writes, in newspaper and magazine publishing: Before you could review a book, you ought to have written one yourself. That’s because publishing a book is enormously difficult. Most people can’t do it. It typically requires years of discipline and toil. Now, however, anyone can play the critic, thanks to Twitter, Tumblr, TikTok, Goodreads, and many other platforms. Online activists sometimes seek to bury books under one-star reviews, as they did to Laurie Forest, author of the young adult novel The Black Witch. Her offense? She heretically suggested to young readers that even people who are prejudiced and have done bad things can learn, grow, and change.

It’s not just young adult authors who have been caught in the crosshairs. In 2020, Jeanine Cummins published American Dirt, a novel that humanized the plight of Mexican migrants by telling the story of a mother and son fleeing cartel violence. Yet the book ignited a furious backlash, beginning with a distasteful takedown by the writer Myriam Gurba, which went viral: “Penjada, You Ain’t Steinbeck; My Bronca with Fake-Ass Social Justice Literature.”

Into the fray, like a cancel-brigade commando, leapt David Bowles, a Mexican-American writer and translator who, despite his accomplishments, is also known for a 2020 profane Twitter meltdown in which he called his critics “disgusting worms.” Bowles inveighed against Cummins’ novel on Medium, in the New York Times, and on NPR. He lobbied against the book in a private meeting with Cummins’ publisher, and petitioned Oprah Winfrey to retract it as an Oprah’s Book Club selection. It took the journalist Jesse Singal—a Dispatch contributor and himself the target of online smear campaigns—to meticulously show that Bowles’ review of American Dirt was so “riddled with unfair inaccuracies and distortions” that “he either read it very hastily or is lying about what is and isn’t in it.” Nevertheless, Cummins’ book tour was canceled after violent threats, not only against her but also against booksellers—tactics that recalled the fatwas hurled against Salman Rushdie.

Often, wokeism’s roots are traced to a supposedly august line of theorists—Foucault on power, Marcuse on repression, Butler on gender, Crenshaw on race. But the lineage really ought to include Lewis Carroll’s Humpty Dumpty, the pompous, pedantic, and delicate egg creature, who said a word means “just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.” According to the left’s moral entrepreneurs, cancel culture isn’t real. The Kansas State University English professor Philip Nel called it a “white-supremacist fantasy.” Similarly, the author Roxanne Gay claimed cancel culture is just a “boogeyman that people have come up with to explain away bad behavior” after their transgressions are justifiably punished. Nel and Gay are both talented performers of what Freddie deBoer calls the world’s “most annoying discursive two-step”: Cancel culture doesn’t exist, they argue, except when it does, in which case it’s obviously a good thing.

You don’t have to be famous or successful to suffer mightily for holding opinions that collide with the censorious left. Just ask Brooke Nelson, who in 2017 was a junior at Northern State University in Aberdeen, South Dakota. She volunteered to serve on a committee for her university’s Common Read program and suggested that the author Sarah Dessen’s young adult novels were too lightweight for college students. She advocated instead for Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy, a memoir about death row injustices.

Dessen shared Nelson’s comment with her 286,000 Twitter followers, thereby kicking off yet another “degradation ceremony.” “F-ck that f-cking b-tch,” tweeted fellow author Siobhan Vivian. (She later apologized.) But even that was too mild a rebuke for Dhonielle Clayton, the CEO of We Need Diverse Books and—wait for it—a sensitivity reader. “F-ck that RAGGEDY Ass f-cking b-tch,” she added.

Fortunately, however, Northern State University’s administrators stood up for their beleaguered undergraduate. Just kidding! Instead, the school tweeted an apology to Dessen, and Nelson deactivated her social media accounts in response to the harassment, though as Szetela compassionately observes, “the first page of Google will remind her what she went through.”

Other moral panics in recent history—around comic books, Satanism, and marijuana, for instance—fell by the wayside after they became so unhinged that reasonable people turned away. But the Sensitivity Era appears far from over. The unavoidable takeaway from Szetela’s sharply-etched and powerfully argued book is that left-wing illiberalism has been institutionalized. It’s already deeply entrenched in schools, libraries, literary agencies, and publishing houses.

Nothing illustrates this better than the fact that while researching This Book Is Dangerous!, Szetela spoke to scores of successful authors, agents, editors, and industry professionals, nearly all of whom refused to go on the record for fear of repercussions. “Even at the most senior level, people are pressured to conceal how they feel,” Szetela writes. One vice president at a major publisher—“literally one of the most powerful people in publishing”—plainly shared some of Szetela’s concerns about the left’s misguided moral crusade over literature. Alas, the executive wouldn’t even let Szetela record the interview, much less be quoted. “Before we ended, they reconfirmed that their name would not be attached to one word they said,” Szetela tells us. As the executive ruefully acknowledged, “a lot has changed in the past ten to fifteen years.” No kidding.