Did you know that the president of France and his wife Brigitte are actually blood relatives in an incestuous marriage? Or that Brigitte is a transgender woman? Or that President Emmanuel Macron was manipulated into becoming the president of France through a CIA mind control program? Or that the Macrons conducted an extensive campaign of violence, fraud, and identity theft to cover all of this up?

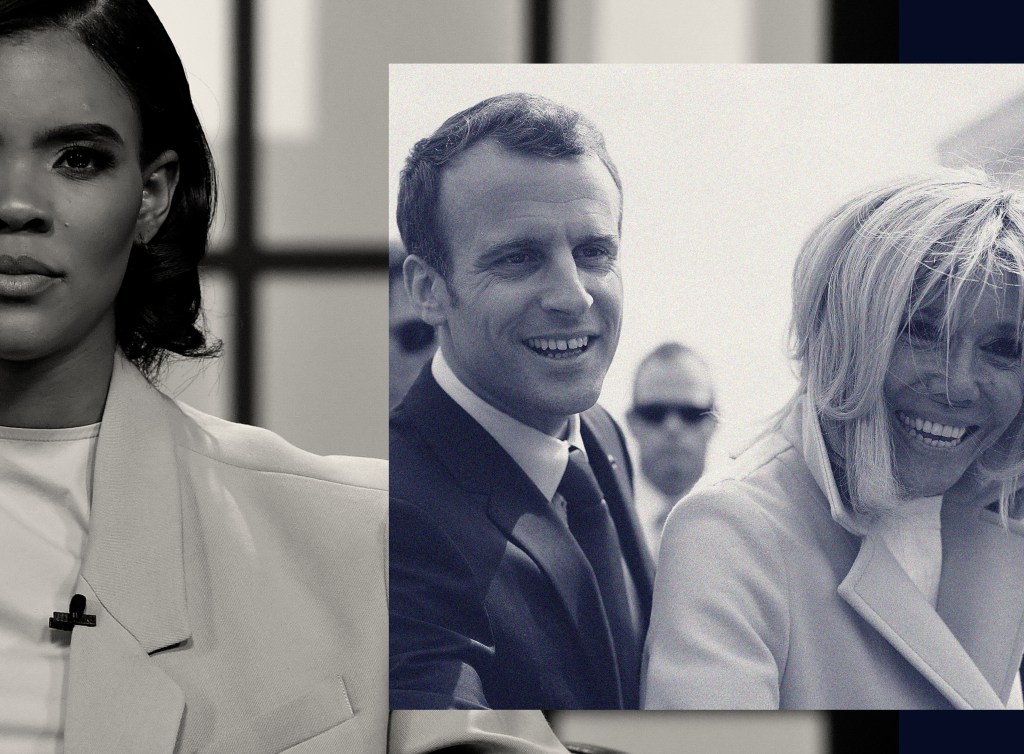

Well, you probably didn’t know this, because nothing would lead a reasonable person to believe any of it is true. But this didn’t stop Candace Owens, a self-styled independent journalist, from propagating that delusional narrative. Over the last year, Owens produced an eight-part podcast, Becoming Brigitte, that placed the Macrons at the center of a vast and incredible conspiracy. In July, the Macrons sued Owens for libel in Delaware.

But the modern rules for defamation liability nearly guarantee that the Macrons will lose. This is an emblem of alarming trends in both journalism and law today. Indeed, modern law encourages the production of liability-free slander that, in the past, would have triggered slam-dunk defamation victories for reputationally injured plaintiffs.

What changed? The Supreme Court made new law in its 1964 decision of New York Times v. Sullivan, in which the Court held that no libel suit involving a public official could succeed unless the plaintiff could prove actual malice. Such a requirement creates an uphill battle for plaintiffs, and subsequent Supreme Court holdings that have fleshed out the test have made that hill much steeper. The modern rule of actual malice is that defamation against public figures requires proof, by clear and convincing evidence, that the alleged defamer either intentionally lied or ignored serious doubts (and thus exhibited “reckless disregard”) about the truth of the statements at issue.

That rule is out of step with much of American law. Consider a court that produces a verdict and apportions damages for a car accident. To determine liability, courts in “fault” states try to work out whether a reasonable person could have avoided the accident, while in “no fault” states, liability is simply assigned for being in an accident, regardless of fault. But no state uses anything like the actual malice rule to determine fault in that context or in most others. Unlike the usual rules of civil liability, the actual malice rule compels courts to focus on the alleged defamer’s psyche—not on outward actions or on standards of reasonable behavior. Instead of considering what a reasonable speaker or journalist would have done or said, actual malice requires the plaintiff to prove that the defendant was either lying or hellbent on indifference. Figuring out what someone was thinking, let alone proving it, is a profoundly difficult task.

Moreover, the plaintiff must meet that burden with clear and convincing evidence—that’s unusual, too. Compare the car accident case: In a fault jurisdiction, a plaintiff must prove only that conduct was unreasonable “more likely than not”—that is, once the law and facts are examined, the balance tips in the plaintiff’s favor. In no-fault states, there is no burden of proof at all. “Clear and convincing evidence,” however, is a much higher standard of proof that forces an uneven balance between plaintiff and defendant. That burden is closer to the prosecutor’s “beyond a reasonable doubt” requirement in criminal law. Proof with “clear and convincing evidence” is most frequently required in civil cases when justice requires demonstration of genuinely wicked behavior—for instance, to support punitive damages or to prove liability for especially shocking medical malpractice.

Perhaps the most troubling implication of the actual malice rule is that it creates a kind of permission slip for sloppy journalism. Consider: The journalist who credibly demonstrates genuine belief in what he or she wrote, however absurd, is free of defamation liability. But the more a journalist asks questions and learns facts that induce doubt about his or her narrative, the more likely the journalist might be subject to defamation liability. In other words, the actual malice standard encourages journalists to ask no questions. It encourages journalists not to do their job.

The Macrons’ 219-page complaint against Owens eloquently demonstrates the absurd hurdles that the actual malice rule creates. In fact, the Macrons’ complaint attempts to get to the goal line by reciting a six-part argument for actual malice 22 separate times. Their argument goes something like this:

Candace Owens had a preconceived mental narrative about what happened before she ever began gathering evidence for what she produced. She relied on obviously biased sources that confirmed her narrative while ignoring the sources she had in her possession that disproved it. Indeed, she had actual knowledge that her preconceived narrative was false because she had access to relatively authoritative sources that disproved it. She refused to retract her story even after being presented with evidence that it was false. Furthermore, her business model encourages her to propagate fabulous falsehoods.

The problem here is that this argument does not quite reach actual malice. If the Macrons’ lawyers merely had to demonstrate that Owens behaved carelessly—or that her behavior violated the most minimal standards of what society expects from a journalist or any reasonable person—they would win easily. But the Macrons must prove Owens intentionally lied or that she intentionally disregarded the doubts that she had. Owens will almost certainly claim to believe everything she publishes.

To be clear, the defendant’s purported belief in her own veracity is not immune to challenge. Suppose the Macrons’ lawyers discover an email that Owens wrote that says, “I plan to lie about the Macrons in my podcast.” Or suppose the lawyers introduce into evidence a past conversation between Owens and a colleague in which Owens said, “I have serious doubts about the truth of my claim that Brigitte is transgender.” That might persuade the court to disbelieve Owens’s self-serving claims of good-faith belief and find actual malice. But such smoking-gun discoveries rarely happen. In their absence, Owens likely wins.

Another line of argument is suggested in the Macrons’ brief, something like: All this stuff about the First Lady’s transgenderism and identity theft and mind control is inherently ridiculous, and so the prospect of Owens actually believing it is not credible, which is to say that if she testifies in good faith that she believes in it, she’s got to be lying. This line of argument might be persuasive with a different defendant. But Owens has a history of purporting to believe weird stuff: She has denied the truth of both the 1969 moon landing and core facts about the Holocaust. In many juridical contexts, such beliefs would invite attacks on her credibility. In an ordinary civil case, this evidence might persuade the court that Owens is not a reasonable person, so she should bear liability. Here, however, her extraordinary public credulity actually bolsters her defense to actual malice.

As the larger implications of the actual malice doctrine have become clearer, many members of the Supreme Court have pointed out its weaknesses. Originally, three of the nine justices who supported Sullivan’s result argued in concurrence that even intentionally false statements about public officials should be immune from liability. They at least recognized that proof of someone’s mental state is a poor fulcrum for defamation liability. Ten years after Sullivan, in Gertz v. Robert Welch, a majority of the court noted the doctrine’s alarming implications: “Plainly many deserving plaintiffs, including some intentionally subjected to injury, will be unable to surmount the barrier of the New York Times test.” More recently, when the Court declined to accept Berisha v. Lawson for appellate review, a dissent by Justice Neil Gorsuch summarized the current state of the law: “Under the actual malice doctrine as it has evolved, ‘ignorance is bliss.’”

In fairness, Sullivan’s architects had good intentions and were trying to solve real problems. The Sullivan court wanted to expand First Amendment protections for journalists and for their extraordinarily valuable work, while decreasing the likelihood that embittered subjects of news stories would retaliate by weaponizing libel actions. These are laudable goals.

But the actual malice rule is a blunt instrument for fine-tuning the plaintiff-defendant balance: The rule simply pays insufficient attention to reputational protection—a foundation of both commercial marketplaces and the marketplace of ideas. Indeed, the actual malice rule can be understood as a kind of predecessor of modern-day proposals for tort reform that are meant to protect classes of professionals: Under this framing, the entities wanting protection in the 21st century are doctors and hospitals; the entities that needed help in the 20th century were journalists and publishers.

Many commentators now place the actual malice rule on a pedestal, as if it is something sacred. They argue that criticism of Sullivan is, in effect, an attack on the First Amendment. But that overlooks Gorsuch’s point: the Sullivan standard incentivizes the publication of falsehoods, and such falsehoods do not add value to a system of free expression. As Gertz v. Welch underscores, “There is no constitutional value in false statements of fact.” It is difficult to defend the proposition that falsehoods contribute to news coverage. I think the better perspective is that the law of defamation should be changed in order to discourage them.

The Owens case underscores how the professional ethics and institutional safeguards of journalism that Sullivan took for granted have eroded (in an age when anyone with an internet connection can broadcast conspiracy theories to millions). Until the actual malice rule is modified, a growing number of “deserving plaintiffs, including some intentionally subjected to injury,” will have nowhere to go to get their reputation back.

That includes the Macrons, who will likely lose their suit under current law. Perhaps their strategy is to appeal a lower-court defeat to the Supreme Court–and to hope that a majority of Justices will be so horrified by the absurd consequences of the status quo that they will produce a new opinion that rewrites our defamation rules. That is, after all, what happened sixty years ago in Sullivan. The status quo is good news for journalists—or pseudo-journalists—who rush to publication with no accountability. For those of us who believe that reputation and personal dignity deserve protection against defamation, lest we sacrifice civility and self-governance, the changes Sullivan triggered have become a tragedy.