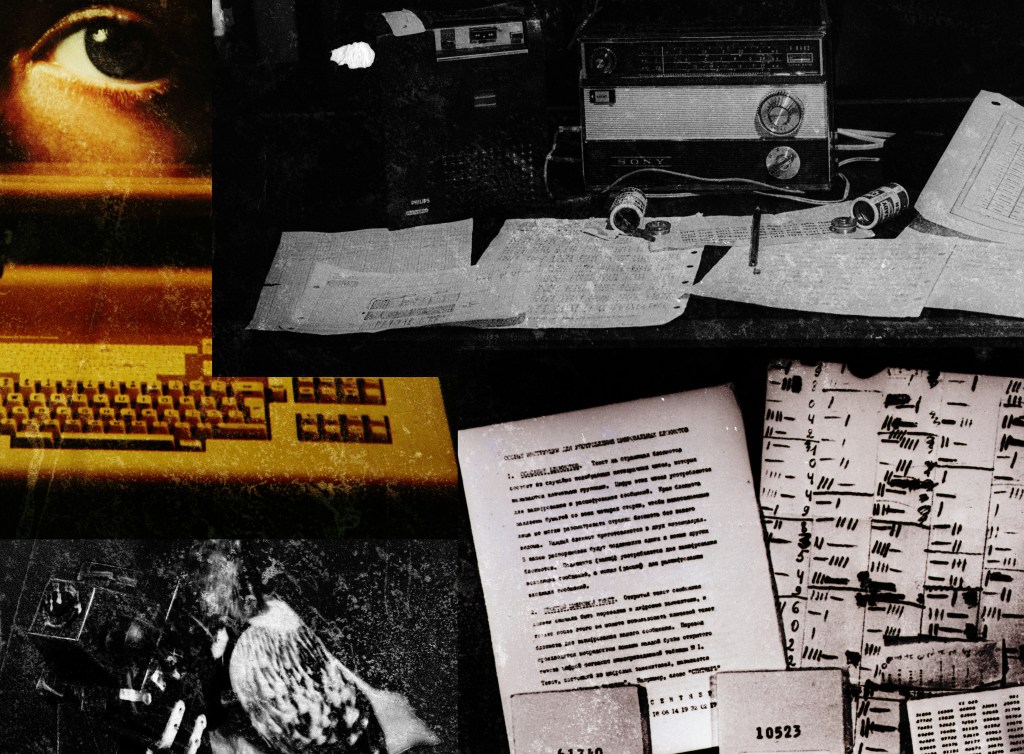

Most Americans think of double agents in Hollywood tropes: a furtive meeting in a distant hotel, a dead drop in a swanky casino, coded messages in dark web chatrooms. In reality, betrayal of one’s country often starts at home, with far more mundane scenes—a sudden financial crisis, a personal indiscretion, a rescinded job offer. History teaches us that insider threats are rarely the product of elaborate foreign machinations. More often, they germinate in the domestic lives of the desperate, disillusioned, and spurned, words that now describe far too many of America’s national security professionals.

In late May, Nathan Vilas Laatsch, a civilian employee of the Defense Intelligence Agency’s Insider Threat Division (which exists to stop leaks), was arrested for allegedly trying to pass information to a foreign government through a dead drop in a park. This would have been a major news story, and perhaps sparked a national debate, had these deeper and longer-term threats not been overshadowed by the Trump administration’s more sensational scandals, such as Signalgate. (This is not to downplay the seriousness of that intelligence breach, or its international repercussions). Worse still, journalism and intelligence work are natural enemies, in the sense that one profession requires uncovering things while the other survives on the basis of them remaining covered. This begs the question: If the intelligence community’s house were on fire, how would the public know?

Under this paradigm of secrecy, the most successful espionage operations are those you don’t hear about. So, while it may be easy to write off easily exposed efforts like Chinese trawling for secrets on LinkedIn as a nuisance rather than a legitimate threat, the risk-reward calculus for foreign agencies on these “dragnet-style” operations is changing. In a very real sense, through both broad actions and those targeting the intelligence community specifically, the Trump administration has fomented the exact conditions that are believed to generate double agents. The motives for unauthorized disclosure of classified information are predictable and generalized into four categories: money, ideology, compromise/coercion, and ego, forming the helpful mnemonic “MICE.”

Money is the most potent incentive, such that financial trouble has long been the most common reason for security clearance denial. It was the primary apparent motivation of Aldrich Ames and Jim Nicholson, some of the highest-ranking CIA officers ever convicted of selling information to Russia, and more recently, the motivation of Navy sailors selling information to China. It is safe to assume that those with security clearances were financially stable when that clearance was granted or renewed, but as national security professionals ranging from the probationary to the most senior are fired without warning or recourse, they are thrust into an imbalanced job market with dwindling comparable positions. Those who survive the mass layoffs face reclassification as de facto political appointees and the risk of arbitrary firing for reporting inconvenient truths or for alleged connections to President Donald Trump’s critics. Whether facing profound job insecurity or already fired, they know that some secrets can be sold for the price of a house or more. As the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) dismissed thousands at once, squandering a strategic investment that can run into the millions per person, it flooded a shrinking sector with at-risk former employees while downsizing the very agencies tasked with counterintelligence.

Ideology, or loyalty to mission, is also imperiled on an unprecedented scale. In the case of Laatsch, the civilian DIA employee who allegedly tried to pass top secret information to what the Department of Justice described as a “friendly” foreign government, his stated motivation hinged on “the values of this administration.” President Donald Trump is known for his toxic relationship with his own intelligence community, and his attempts to assert control have been poorly received, but the issue runs far deeper. An America that is distancing itself from core allies in favor of Russian interests, led by a president intricately connected to the Russian head of state, would have once been unfathomable. It goes against the ideological foundations of American intelligence. Even in cases where it is not a primary motivation, ideological erosion may still engender a sense of nihilism in which other motivations could flourish.

Compromise and coercion are more dramatic but less common ways for adversaries to elicit collaboration, but these risks are also increasing. The way in which parts of the federal government have been fed “into the wood chipper” has multiplied both physical and digital entry points, opening new opportunities for hostile intelligence agencies to obtain leverage. Beyond the obvious risk of suddenly jettisoning standard cybersecurity practices across the federal government to enable DOGE’s quest for limitless data access, there is a more esoteric danger: that the aggregation of data presents a security risk in and of itself. If this weren’t enough, in an extraordinary confluence of harmful acts, the identities of intelligence officers were exposed in unencrypted communications at the same time as they were being fired, in some cases reportedly without so much as an exit briefing. This creates a nonzero chance that intelligence professionals could have been compromised and then given opportunities to surreptitiously access sensitive materials during their chaotic off‑boarding.

Finally, ego can be broken down into disgruntlement/revenge, ingratiation, and thrills/self-importance. It may seem petty, but many intelligence disasters spring from bruised pride or a need for validation. Edward Snowden was apparently upset at the insufficiency of a job offer. More recently, Jack Teixeira sought to “impress anonymous friends on the internet” by leaking classified documents about the war in Ukraine. By denigrating, interrogating, and potentially even spying on civil servants, the Trump administration does damage to the ego (and the morale) of these officials at every turn. The nonstop barrage of media coverage is an inescapable reminder of the insult.

Deeply troubling structural risk factors are amplifying the already-elevated MICE threat. While the current number of people with a U.S. government security clearance is unknown, the last count in 2019 estimated there to be 4.2 million. Whether that is too many, too few, the product of overclassification, or an irrelevant number are all topics of debate, but everyone agrees that the current system for protecting classified information is far from airtight.

The DOGE layoffs compounded these structural risks: An ever-growing amount of classified material now overwhelms a shrinking pool of specialists. The immediate solution—the next generation of the intelligence community—is being cut from the federal payroll, and cannot be quickly or cheaply replaced while the process for obtaining a security clearance remains complex and backlogged. By hacking away at intelligence in its quest for “efficiency,” DOGE may have positioned America to pay in blood, not dollars, and the cuts might not even generate net savings.

Either way, someone has to say it: The next high-profile espionage case won’t surprise the experts. We are not just watching a catastrophe approach, we’re building one from our own blueprints, step by step.