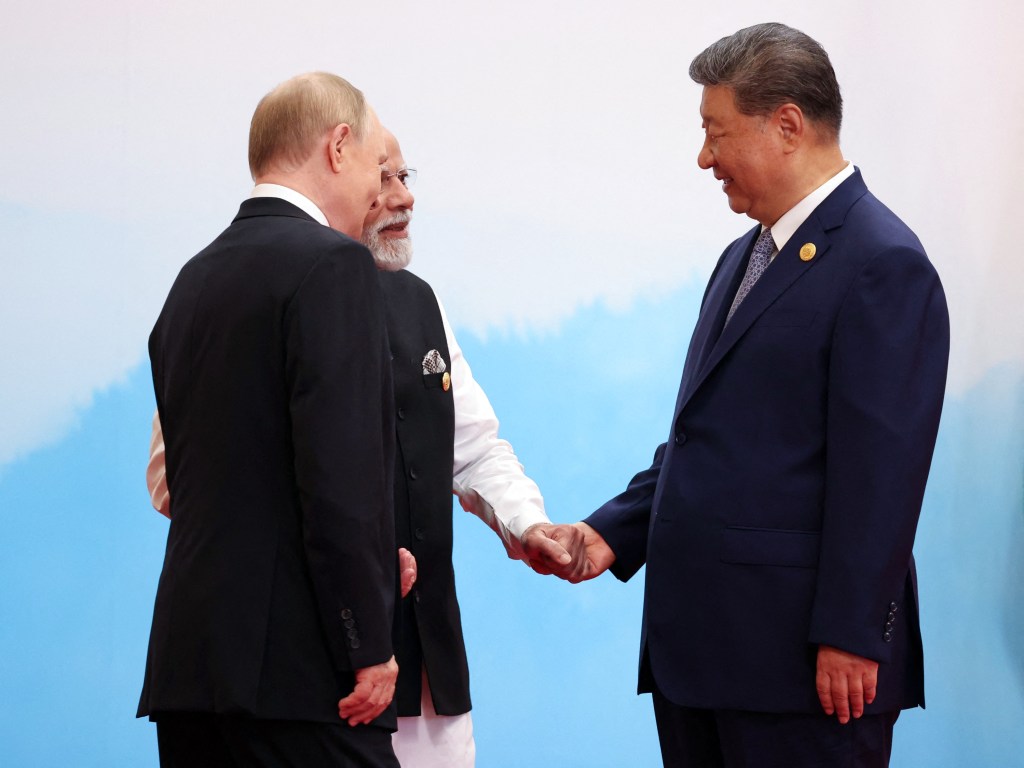

Russian caudillo Vladimir Putin was there, too. Russia and China also have a long history of territorial disputes, though these have been resolved relatively recently. It is tempting to write that they have been resolved “on paper,” but they apparently haven’t even been really resolved on paper, with Beijing publishing maps that claim Chinese authority over supposedly Russian territory.

There were other awkward pairings: Turkish strongman Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was at the SCO, and so was his Armenian counterpart, Nikol Pashinyan—two heads of states that have no official diplomatic relations and whose peoples have been mutually hostile toward one another for 1,000 years or so. Egypt and Iran, which have been inching toward a normalization of their relationship, sent their president and prime minister, respectively.

Beijing has thus made another robust display of what is known in diplomatic circles as “convening power,” the ability to get disparate and even hostile parties to sit down together to work through issues of shared concern. The issues that brought together these countries are—here is the revealed priority—powerful enough to overcome concerns about past and future wars, territorial disputes, a little bit of military occupation here and there, nuclear terror, and more.

The brain-dead partisan will here be tempted to say, “Thanks a lot, President Trump!” And there is a pretty good case to be made that the Trump administration’s incompetent diplomacy and whatever-is-on-the-far-side-of-moronic trade antics have driven India, a natural U.S. ally (an English-speaking, trade-oriented democracy with predatory Chinese nationalists on one side and mad jihadists on the other), more intimately into the orbit of one of the two countries with which the Republic of India has fought an actual war. A 50-percent tariff (or, you know, 100 percent or whatever) can even propel India to take a seat at the SCO alongside the other country with which India has fought a war, which also happens to be the country it is most likely to fight a war with in the foreseeable future. Informed in 1959 that China was building a highway through Indian territory in Ladakh, a placid Jawaharlal Nehru remarked: “Not a blade of grass grows there.” Mess around with an $80 billion export market, on the other hand, and you will ring all sorts of bells in New Delhi.

But there is more to it than that, of course. In the Cold War years, India held itself out as a “nonaligned” country, but it has an awful lot of Russian jets in its air force, having cultivated close military links with Moscow since the Soviet era. And it did not go unnoticed in India that its archrival, Pakistan, enjoyed generous U.S. support in those years—the Pakistani regime, Indians used to say, rested on the “three As”—the army, Allah, and America. Neither India nor China is very much inclined to support U.S. efforts to wage economic warfare against Russia as a matter of general principle, and both are even more intensely disinclined to toe Washington’s line when there is a great gusher of bargain-basement Russian petroleum to be had on easy terms.

A fair, charitable, and realistic reading of India’s attitude might be that it is, as a practical matter, genuinely nonaligned as far as the Russia-Ukraine war goes. Modi is a nationalist who believes that India’s business is India, and that seeing to India’s business means keeping a line open for that Russian oil and military hardware, maintaining productive relations with the behemoth next door, and prioritizing these over making democratic happy talk with Washington, which increasingly shows itself to be lacking credibility as an ally and—even worse—as an enemy. Modi is not a stupid man, and he knows that if he really needs something from Donald Trump, then he can flatter Trump and bribe his friends and family in some obvious but non-actionable way and get what he needs. Critics call him a religious fanatic, but think of him as a less sanctimonious J.D. Vance.

The Egypt-Iran pairing at the SCO exemplifies similar dynamics. The leaders of those two countries (to say nothing of their people) have not suddenly discovered a bottomless well of mutual respect and friendship. They have seen the dynamics of their region transformed by a number of factors, including a normalization of Iran-Saudi relations—in a deal brokered by China. If the Saudis can talk to the Iranians, the thinking goes, so can the Egyptians and other Arabs. The Israel-Iran confrontation has raised shared concerns about military security and energy security. When Iran wanted to reach a technical agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency, which was signed last week, Egypt brokered the deal and hosted the negotiations.

All of this apparently is consistent with Beijing’s philosophy of international relations. And there is more to that philosophy than nationalism, ethno-nationalism, imperialism, socialism, and calculating self-interest. Of course, all of those things are important factors, but there is another sensibility at play. The elderly tyrants of the Chinese Communist Party are not Western-style liberals, democrats, or humanitarians. They are shrewd and cruel, and they are as vulnerable to the “passions” that the American founders warned us about as any majoritarian or demagogue facing a vote. The Chinese vision may be monstrous in ways, but monstrousness is not all that there is to it.

Think of it as “Chinese exceptionalism.”

The most eminent intellectual advocate of Chinese exceptionalism is Zhao Tingyang, a professor at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, who has dedicated much of his work to reinvigorating and recontextualizing the political concept of tianxia. What’s that? In the words of China analyst Henry Hopwood-Phillips—who is far from being an admirer of Zhao’s:

Tianxia is shorthand for a traditional Chinese vision of a world order in which states govern their relations on the basis of Confucian norms of filial piety, benevolence and the “five relations” of ruler-subject, father-son, husband-wife, sibling-sibling and friend-friend. Each involves specific duties and expectations for maintaining moral conduct. Tianxia’s substance, however, is less important to the Chinese state than its ability to discredit the chaotic, selfish and poorly-structured status quo of the U.S.-led international order, in which America monopolizes the legitimation of violence. Conversely, tianxia is advertised as capable of managing global interests in a manner that avoids hegemonic relations.

Among Hopwood-Phillips’ criticisms is the charge that “Zhao shrouds claims of Chinese exceptionalism in clothes made of liberal silk.” He is far better suited to make that judgment than I am, and I do not doubt the merit of his insights. But at the same time, Zhao’s work is at times very liberal-sounding while also enjoying (or at least seeming to enjoy) a great deal of prestige and influence in Beijing’s circles of power. And while Zhao may deemphasize or soft-pedal a few tricky points—e.g., that the Middle Kingdom has been and remains the natural metaphysical center of the world—it is interesting to consider the way that Beijing’s revealed preferences for managing a world order coincide with Zhao’s philosophical musings.

That begins with the seemingly paradoxical nature of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which is something that looks for all the world like a multilateral institution for states that range from those which are indifferent to multilateralism as such to those that seek to cynically exploit multilateral institutions to those that are positively hostile to the entire notion of a nation’s being constrained by such a thing or by the notions associated with such institutions. Beijing sees the world in bilateral terms, a matter of state-to-state relationships rather than encumbering, NATO-style alliances, and it sees states as autonomous and equal in the sense that two boxers in the ring are equals—equally entitled to enter the ring, not that one of them isn’t going to win and the other lose. In Zhao’s formulation, a state or a civilization (no points for guessing which one!) offers a kind of focal point precisely by possessing and deploying a grander version of the kind of convening power Beijing showed off at the SCO. Other states associate with it for their own benefit through a kind of organic process. No, that is not the view from Tibet or Taiwan—but even whitewashing is useful to observe for what it might teach us about a state’s aspirations. In Zhao’s view, the goal is not simple bilateralism at all but a kind of larger philosophical cosmopolitanism, the evolution of international politics into world politics.

Zhao’s Redefining a Philosophy for World Governance is a book I have been recommending to the China-curious for a few years now. (N.B.: I am by no means a China scholar or a China expert, my experience with the country being about 40 hours in Hong Kong, the contents of five or six books, and what I read in the papers. I am curious and trust that readers are curious enough to follow me down the rabbit holes of my enthusiasms.) In it, he writes:

The world order has two traditions: imperialism invented by the Romans and the Tianxia system invented by China. These two are parallel but different concepts. Although both have “worldness” perspectives, they are very different in their visions about how to construct a world order. While both envision a universal world order, the imperial system seeks to conquer and achieve a dominating rule, while the Tianxia system, on the other hand, tries to construct a sharable system. We may say that the Tianxia system aims to create a world system that can become a benevolent “focal point” for all . …

We need to notice that imperialism and hegemonism are failing rapidly in a globalized and universally technological world. Therefore, we need another world outlook.

From Hopwood-Phillips’ point of view, Tianxia is not a substitute for hegemonism—it is Beijing’s gussied-up attempt to assert itself as the natural hegemon, a fact that is easier to see the closer you get: “Laos and North Korea, for instance, are left alone thanks to ideological alignment,” he writes, “while Cambodia and Myanmar are forced to adjust to forms of clientelism.”

But of course clientelism, ugly as the word is, must be based on shared interests, too—that is what distinguishes a client state from one that is merely vanquished. And it is not as though Beijing’s success in such areas as the “Belt and Road” initiatives came at the point of a bayonet or that poor countries have been tricked into accepting those infrastructure development funds and aid. Beijing has a lot of money sitting around and would like to expand its access to markets here and there; the powers that be in Kazakhstan and Kenya want better ports and railroads and such. Building a new high-tech Silk Road serves those shared interests. Of course, Beijing is acting in self-interest. Of course, Beijing wants to use these projects to further non-economic interests and is not acting from some kind of disinterested or philanthropic love of international development. Beijing rightly sees these projects as being built on not only Chinese capital and Chinese expertise but on a foundation of Chinese norms and assumptions and politics. It isn’t do-good-ism, it isn’t liberalism, it isn’t democracy, it isn’t humanitarianism—but it isn’t just raw imperialism, either.

History has taught us that it has always been hard to resolve the issue of “the one and the many” in politics. It is almost impossible to have a perfect system that sets up a common order acceptable to all political parties. [N.B.: “Parties” here implicitly means “states.”] For example, the issue of national politics has until now never been able to evade Plato’s political curse, namely that a national political system is no more than cyclical alternations between the two extremes of dictatorship and democracy. No system that is positioned between these two extremes can sustain its advantages for long and will eventually decline and swing to one end or the other. Though Plato did not offer sufficient proof for this insight, history seems to be on his side as it constantly bears witness to its validity. Compared with the issue of national politics, world politics is even more challenging. A country with a long history of unification usually carries some collective uniformity , such as in religion, language or history, or at least shares some common interests. However, the world has until now not shown any uniformity or sharability in spirit or interests. So, today’s world remains a mere geographic space, rather than being commonly shared, indicating that it is still in an anarchy. In essence, the world remains in a primitive and natural political state. The introduction of a world politics that can construct a political world is yet to take shape. What we have now is only so-called international politics. This is not the same as world politics, but just a derivative of national politics: strategies for international competition that cater only to national interests. Consequently, international politics still retains its natural primitive nature, rife with conflicts and hostility. The strategies of international politics, based on non-cooperative games, are quintessentially hostile to world politics. Therefore, we need to search for another approach to construct the political world, a new politics that can transcend hostilities.

After the SCO, there was a gigantic military parade. Donald Trump apparently kept angling for an invitation that never came, and he had a good time last time he was in China, feted like an emperor. There was a remarkable picture of Xi Jinping with Putin on one side and Kim Jong Un on the other. No North Korean leader had attended such an event in China since Kim Jong Un’s grandfather, Kim Il Sung, who was not invited to stand next to Mao Zedong in the place of honor. (Mao was flanked by Ho Chi Minh and Nikita Khrushchev. Kim Il Sung was down on the far side of Zhou Enlai and Mikhail Suslov, who was not even a head of state but merely the foreign minister of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.) The photo of Xi, Putin, and Kim was remarkable for its elevation of the North Korean tyrant. Of course, Xi must regard Putin as very much a junior partner, but Kim is the bossman of a barely functional psycho-state. If that is clientelism, Kim must be very happy to be such a client.

The juxtaposition of the SCO and the military parade was not an accident of the calendar. Perhaps Zhao watched it and reflected on his own words: “Rule by force is not politics, but just a way of ruling; true politics is an art that creates universal cooperation and coexistence.”

One could take an unsentimental view of American exceptionalism: “This is our country, these are our values, we believe them to be good and true, to be the basis of any decent and humane society, and they have made ours the most successful country in the history of the world. We invite you to share in these values. Also, we can and will stomp you into goo if you give us a lot of trouble.” Chinese exceptionalism is not a mirror image of American exceptionalism, and universalist-triumphalist Tianxia is not a mirror image of universalist-triumphalist liberalism—but it may be worth considering that there is more of a family resemblance than is immediately apparent. Nobody ever thinks he is the bad guy in the story—and while it is important to keep a very skeptical eye on what Beijing is doing, it also is worth the effort to try to figure out what Beijing thinks it is doing, which, presumably, isn’t some kind of Dr. Evil or Ernst Stavro Blofeld caper—or what Hitler or Stalin were up to and about, either.

And it is worth meditating for a moment on the alternative currently on offer from Washington, where the ladies and gentlemen in power seem to have forgotten their Talleyrand while rewatching Goodfellas for the 93rd time, as though “F—k you, pay me!” were a sustainable strategy worthy of this republic.

Economics for English Majors

A brief thought about the work China has been putting in for all these years to build that new Silk Road: It is remarkable that while China is working to build out the infrastructure of trade, understanding that this works to China’s advantage—economically and politically and culturally—the United States has laid a heavy (and unconstitutional) tax on its people to protect us from abundance and low prices. The world brings its best produce to our shores and lays it at the feet of our people, and we Americans complain that the prices are too low. As a matter of economics, that is difficult to understand; it is much easier to understand as a matter of extortion and rent-seeking.

Words About Words

A while back, I wrote that it is foolish and pointless to blame a pest for being what it is: “You cannot hate a mosquito—you can only swat him.” A reader responded: “I believe only female mosquitos bite. So it probably should say, ‘—you can only swat her.’”

Well, I’m not sure how they get “assigned at birth,” but I am pretty sure there are only two mosquito sexes, and I hate them both.

In Other Wordiness …

About the top item: What does it mean to “get Shanghaied?”

To get Shanghaied is to be kidnapped. The original meaning was to be kidnapped and then pressed into service as a sailor. People who engaged in this were known as crimps. But why Shanghai? Nobody really knows.

We know why it wasn’t Lubbock, Texas, or Allen, South Dakota, the U.S. municipality that is furthest from an ocean or gulf, 1,012 miles from the shore. Apparently there is a geographic term for such a place: the “inhabited pole of inaccessibility.” Obo, in the Central African Republic, is a continental pole of inaccessibility.

The closely related phrase “inhibited pile of inaccessibility” describes the prose style of the typical Ivy League college professor in the humanities circa 2025.

Elsewhere

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can check out “How the World Works,” a series of interviews on work I’m doing for the Competitive Enterprise Institute, here.

In Closing

From Abraham Lincoln’s first inaugural:

[block] We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection.[end block]

From Lincoln’s second inaugural:

Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword as was said three thousand years ago so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’

There are those among us who pray fervently for a second civil war. I cannot imagine why. Maybe they are bored. Maybe they have forgotten what goodness and sweetness are like, or maybe they never knew to begin with. “The judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.” If Americans are praying for anything, it should be that we know more of His mercy than His righteousness.