Sunday’s election for the 101-seat Moldovan parliament was a victory for pro-European politics in the country of 2.4 million people, wedged between Romania and Ukraine. The Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS), which advocates for joining the European Union and greater security cooperation with NATO, led with 50.1 percent of the vote as of Monday morning, easily outpacing the pro-Russian Patriotic Electoral Bloc and the populist Alternativa, with vote shares of 24.2 percent and 8.0 percent, respectively.

PAS’s winning margin makes it highly likely that Moldova’s president, Maia Sandu (a PAS member), will be able to form a government without relying on any other parties. Sandu and other PAS politicians had cast Sunday’s vote as existential: “Moldova, our dear home, is in danger and needs the help of each of you,” Sandu said after voting on Sunday morning. The stakes, she had repeatedly warned, were nothing less than Russian “control” of the country.

The coalition of parties that ran against PAS, the Patriotic Electoral Bloc (BEP), claims that it only wants peace and campaigned on a platform of permanent neutrality and “friendship with Russia.” However, that relationship is often more than neighbourly.

Two parties—Heart of Moldova and Greater Moldova (part of the BEP)—were banned from competing in Sunday’s election on Friday, after an electoral investigation commission found that both parties worked with Russian political activists, used illegal financing, and attempted to bribe voters in advance of the election.

However, it’s unlikely the bans had much of an impact. “All the fundamentals are basically the same,” David Smith, a Moldovan-based political analyst, told TMD. Heart of Moldova voters still had other options in the BEP, and Greater Moldova had never really been considered a serious contender.

Igor Dodon, a former Moldovan president who leads the BEP-aligned Party of Socialists, claimed without evidence on Sunday that Sandu was planning to annul the election results, stating that it was “already clear” his coalition would win, and called for a rally on Monday outside the parliamentary building. In one recent TikTok video, he labeled Sandu a “DICTATOR.”

Dodon’s social media claims dovetail with the efforts of a massive Russian influence operation uncovered this summer by Moldovan investigative journalists. Regional groups coordinated through Telegram, a secure messaging platform, were trained as “activists” and charged with disseminating Russian propaganda, such as claims that Russia was leading a global fight against fascism or that PAS was intent on releasing serial killers from prison. Participants received prizes, such as phones, for posting and for inviting more “activists” to the group, and were paid in cryptocurrency or from accounts opened with Promsvyazbank, a Russian bank that has already been accused of enabling a Moldovan vote-buying scheme in 2024. While those running the Telegram groups were vague about who, exactly, paid them, it was clear that social-media operatives were working with the Victory Bloc, a group of political figures associated with the oligarch Ilan Shor.

Shor, the heir to a Moldovan business empire, is one of the most prolific bank robbers in history, stealing nearly a billion dollars in 2014 through a fraudulent loan scheme. He was sentenced to more than seven years in prison in 2017, but Shor fled the country, living first in Israel and then in Russia, where he is now a citizen. Still in exile, he financed a vote-buying campaign that Moldovan authorities claimed had paid 130,000 people during the 2024 election—likely contributing to the much narrower-than-expected 50.4 percent “yes” win in the connected EU referendum—and his activities continued, using ever-more-complex financial workarounds, through this election. In the past year, Shor created a ruble-backed cryptocurrency to anonymously pay Moldovan agents and launder billions of dollars of Russian money.

Russia has also attempted to infiltrate Moldova physically, not just digitally. The Wagner Group, a mercenary organization associated with the Russian government, trained Moldovan nationals in drone operation and riot tactics last year at training camps in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, in an attempt to disrupt the 2024 presidential election and EU referendum. Around 300 Moldovans are also alleged to have participated in a similar training scheme outside of Moscow.

Fast forward to last week, and Moldovan police conducted 250 raids and detained 74 people, who officials said had travelled to Serbia to receive “training for disorder and destabilization.” Police also said they had seized cash and weapons during the arrests, and accused at least one GRU (Russia’s military intelligence service) agent of coordinating the trainings. One day after the raids, police announced that they had disrupted an online cash-transfer scheme in the city of Balti, seizing $50,000 and identifying around 10 times that amount linked to transfers related to a “criminal scheme” planned for Sunday’s election.

Eugen Muravschi, an associated expert at Watchdog.MD, a Moldovan election interference monitor, told TMD that the police have become more successful at disrupting these schemes and proactively combating online disinformation. “I think it’s a significant improvement this year,” he said. However, he also cautioned that even if PAS won a clear victory on Sunday, Russian interference efforts could continue.

Along with the planned Monday rally by BEP, Dodon’s claims of interference, cyberattacks, and bomb threats could all be sources of instability in the days to come. “They will try to do something if they don’t have a majority,” Muravschi predicted, even though such a gambit might be a long shot.

Moldova, however, is simply the most extreme example of Russia’s attempt to expand its influence over Europe, using methods that go right up to the edge of war. In the past several weeks, Russia has sent fighter jets into Estonian airspace, prompting Italian aircraft to scramble in response; Russian drones have flown over Poland and Romania, with some being shot down by the Polish military; and a Russian warplane buzzed a German Navy frigate in the Baltic Sea. Mysterious drone activity has also shut down airports in Denmark and Norway in recent weeks, and on Sunday night, NATO jets and air defenses were deployed, and Poland shut down parts of its airspace, in response to Russian strikes on Ukraine.

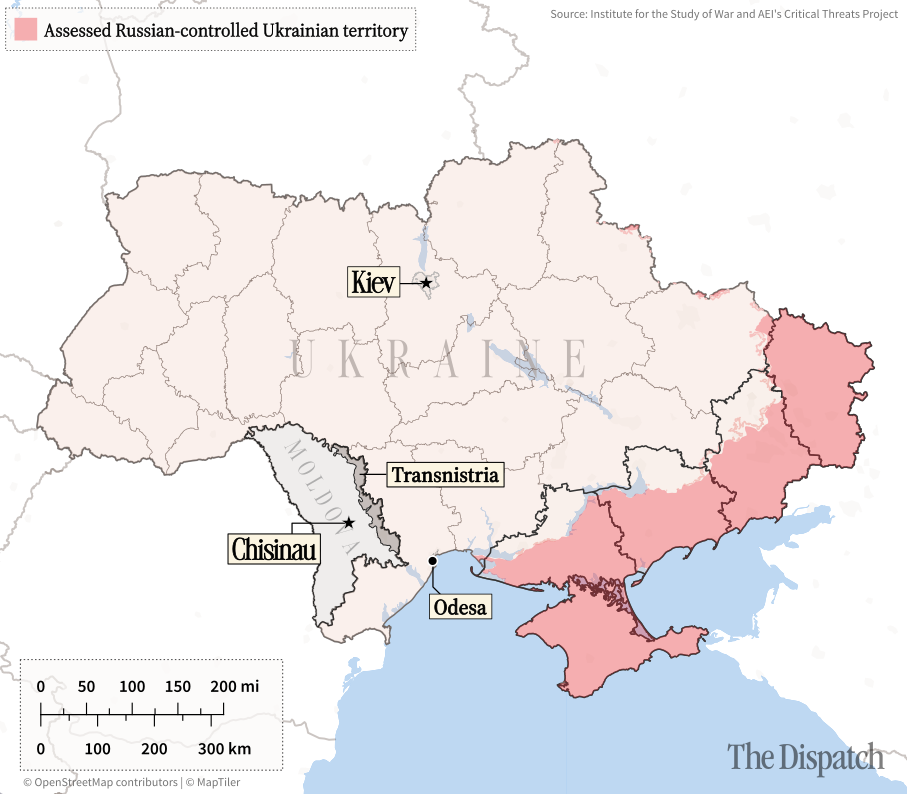

If Moldova were to become a welcoming host to Russian operatives, provocations against Europe could increase even more, Iulia Joja, the director of the Middle East Institute’s Black Sea Program, told TMD. “You could see Moldova turning very quickly into a launching pad” for drones and jets flying sorties over Europe and Ukraine, she said. Ecaterina Locoman, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Lauder Institute, also told TMD that Russian access to Moldova would make Ukraine “far more vulnerable,” forcing it to commit even more forces to the defense of the country’s southern coastline: the crucial port city of Odessa is under 40 miles from the Moldovan border. Thousands of Ukrainian troops are already stationed near the Moldovan border, away from the front lines in the east, and an increased Russian presence in Transnistria, a largely pro-Russian breakaway region that already hosts Russian “peacekeepers,” would require Ukraine to increase that commitment.

Currently, the Russian forces in Transnistria are poorly trained and equipped. But Ukrainian military leaders have been warning for years about Russian plans to reinforce them with around 10,000 troops. Although Moldova doesn’t share a land border with Russia, Smith cautioned that the Kremlin could use covert means to slowly move soldiers into the country. If men—who may or may not have links to the Russian military—slowly filtered through Moldovan border checkpoints, it could become a reprise of the “little green men:” troops in unmarked uniforms who were the vanguard for Russia during the Georgian conflict of 2008 and the seizure of Crimea from Ukraine in 2014.

Russian leaders have protested that they harbor no aggressive intentions toward Moldova, or toward the rest of Europe (besides Ukraine). Russia “does not have any intentions” of attacking NATO or Europe, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov proclaimed at the U.N. General Assembly last week. But he also promised a “decisive response” to Western countries that threatened Russia. Russian officials also said last week that they had nothing to do with Moldova’s election, calling reports of interference “imaginary” and accusing Sandu’s government of anti-democratic practices and anti-Russian “hysteria.”

But rather than engaging in hysteria, on Monday morning, Moldovans who favor a pro-European future for their country were likely relieved. After years of Russian attempts to dominate its country’s politics, Moldova, with a population almost 50 times smaller than Russia’s, is still moving toward the West.

“Today, in our country, democracy is in the hands of Moldovans,” Sandu said. For now, that appears to still be true.