Elections went smoothly, with final results expected to be announced later today. However, they also highlighted that al-Sharaa’s new government still faces a challenging road ahead, with the process marred by concerns about top-down decision-making and with elections postponed indefinitely in some parts of the country.

Al-Sharaa’s visit to the U.N. General Assembly in September, the first by a Syrian president in nearly 60 years, is a sign that the rest of the world is eager to welcome his country back from the isolation of the Assad years. But even if al-Sharaa’s transformation from jihadist to secular statesman is sincere, his commitment to transparent, accountable government is more ambiguous. Along with a nonbinding, one-day “National Dialogue” in February, a seven-member committee selected by al-Sharaa set the rules for Sunday’s election.

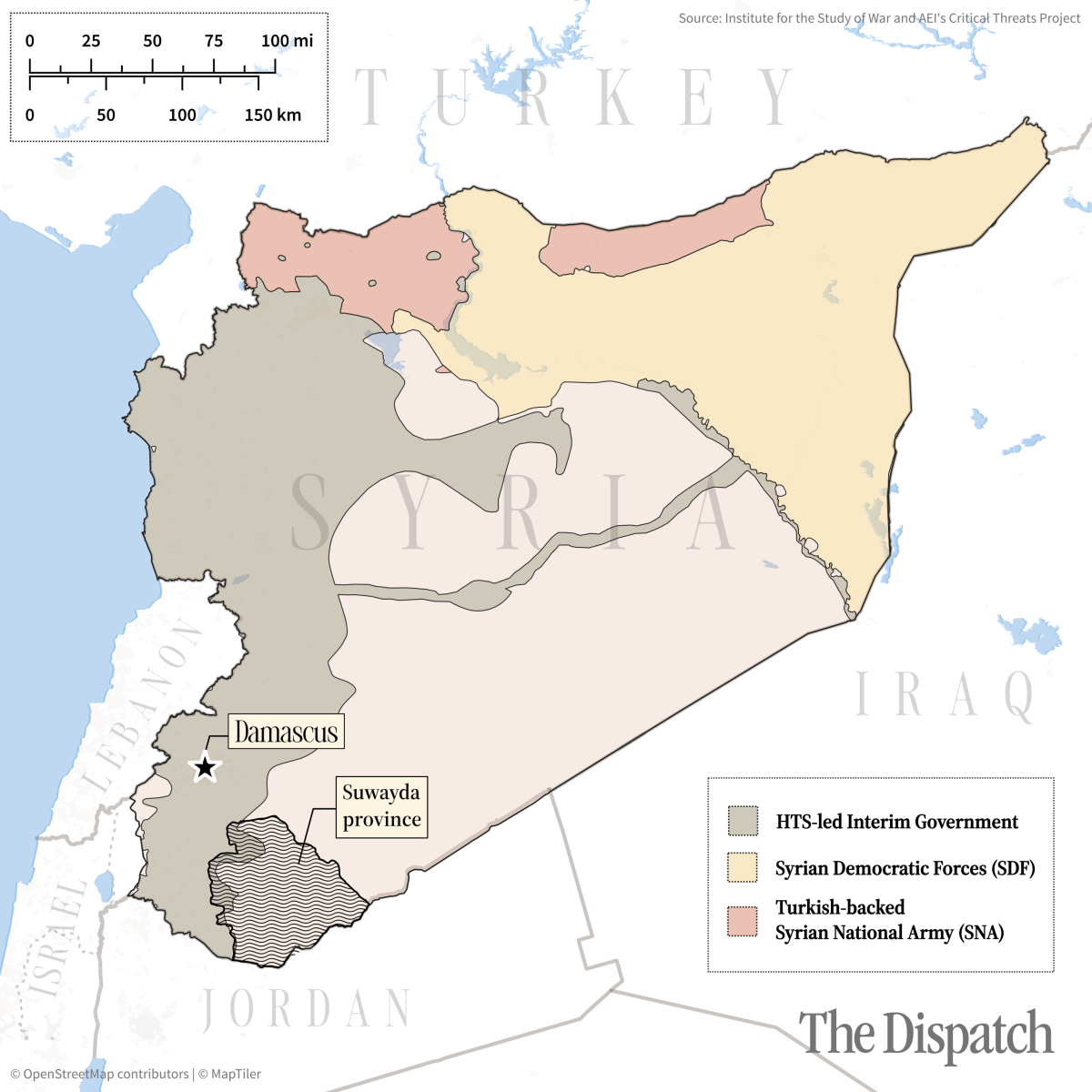

However, few Syrians actually voted. A Supreme Committee (again handpicked by al-Sharaa) appointed subcommittees, which then selected approximately 6,000 regional electors across the country to vote in about 120 members of the 210-seat People’s Assembly. al-Sharaa will appoint an additional 70 members, and roughly 20 additional seats will remain empty for now, with the government indefinitely postponing voting in northeastern Syrian areas controlled by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and a southern province controlled by members of the Druze minority.

Critics charge that the entire electoral process was opaque, with limited popular participation and excessive influence from the president. There are also no quotas to ensure the parliamentary representation of women and minorities, although draft electoral college rules required that 20 percent of electors be women. “This is the biggest concern with the new government,” Nanar Hawach, the senior analyst for Syria at the International Crisis Group, told TMD. “It’s how centralized power is within a handful of people.”

In his first months in power, al-Sharaa seems to be running much of his government through a small, tight-knit circle of advisers. Foreign businessmen claim that his brother, Hazem, who does not currently hold a formal position, is the primary decision-maker for government contracts, and al-Sharaa’s powerful foreign minister, Asaad Hassan al-Shaibani, has moved into Assad’s former residence in Damascus. Al-Sharaa is also the chair of Syria’s new sovereign wealth fund and has the power to select its board, with little legal oversight from the Finance Ministry. Several of its initial investment deals have been with what some experts describe as obvious shell companies.

Defenders of the new government pointed out that a fully modern election is simply untenable in Syria as it stands, as millions of Syrians have been internally or externally displaced, and basic facts like addresses and population counts remain murky. The new assembly will also be tasked with making plans for popular elections during its 30-month term.

And then there are the areas where the government indefinitely postponed elections, a result of sectarian tensions that have become worryingly heightened in recent years. Syria has always been a diverse state, composed not only of Sunni Arabs (the majority) but also significant populations of Christians, Alawites (a small Muslim sect that the Assad family hailed from), Kurds, and Druze. The new government has struggled to incorporate these groups, leading to violent incidents, like the fighting around the city of Sweida earlier this summer.

The incident was an example of how severe the divisions between the central government and regional minorities have become. Located in the south of Syria, near the border with Israel, Sweida’s population is majority Druze. Members of an insular, syncretic religion that combines aspects of Islam, Christianity, and various Middle Eastern mystical traditions, the Druze made up around three percent of Syria’s pre-war population.

In July, armed Bedouins (desert-dwelling tribal groups) kidnapped a Druze merchant on the highway between Sweida and Damascus, beating him and stealing his goods. In retaliation, the merchant’s relatives kidnapped Bedouin tribal members in Sweida, leading to another round of counter-kidnapping.

The violence quickly spun out of control. Militias from both groups mobilized, with Bedouins entering the province from across the country, passing through Sunni-run government checkpoints to do so. Al-Sharaa sent government forces to restore order, but Druze militias, convinced that the government was allied with the Bedouins, fought back. Syrian vehicles were also targeted by Israeli jets, intervening on behalf of the Druze. Israel also attacked the Ministry of Defense in Damascus, striking near the presidential palace. By the time the U.S. helped to broker a ceasefire on July 19, around 1,000 civilians and militants had been killed. Israel claimed that it intervened to protect the Druze, as a large number of Druze live in Israel and serve in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). Israel has also sought to expand its zone of influence in Syria in the past year, creating a buffer between its border and Syria’s to forestall cross-border attacks.

July’s fighting, however, wasn’t the only outbreak of bloody sectarianism under the new Syrian regime. Multiple ambushes and massacres, purportedly by government-aligned forces, killed dozens of Druze last spring and prompted limited Israeli strikes. In March, three weeks of fighting and massacres in Alawite-majority areas of western Syria—between former members of Assad’s forces and armed groups aligned with the new government—killed as many as 2,000 people, according to civil rights observers, and caused thousands of Christians and Alawites to flee into Lebanon.

There hasn’t been as much violence between the SDF and the new government, but the signs so far are not encouraging. While dominated by Kurdish armed groups (including the all-female Women’s Protection Units), the SDF has included a host of other groups that fought against Assad and the Islamic State, including the Syriac Military Council (made up of Christian Assyrians), various Arab militias, and at one point, the International Freedom Battalion, made up of leftist foreign fighters.

With a commitment to secularism and local democracy, the SDF has been remarkably successful at working across Syria’s sectarian divisions. “Northeastern Syria is the most integrated region of Syria,” Michael Rubin, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, told TMD. “It should be the model for the rest of the country.”

Following its seizure of Damascus, al-Sharaa’s government has sought to incorporate the SDF’s territory. However, amid skirmishes between government forces and SDF groups this summer, negotiations to integrate SDF forces into the new Syrian armed forces have largely stalled. SDF-aligned groups, especially Kurdish forces, are deeply wary of Turkey’s support for al-Sharaa, as Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has sought to prevent the growth of Kurdish power on his country’s border and stave off new influxes of refugees.

On Wednesday, Erdoğan hinted that Turkey might intervene if negotiations fail. “We have engaged all channels of diplomacy both to preserve Syria’s territorial integrity and prevent a terrorist structure from forming across our borders,” he told the Turkish parliament last week. “Turkey will not allow a deja vu to take place in Syria.” Turkish troops have fought with the SDF in years past, carving out a buffer zone in parts of northern Syria.

But despite Turkish pressure, the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES)—the SDF’s civilian authority—has not yet recognized the legitimacy of Sunday’s elections, calling them “an attempt to reproduce the exclusionary policies that have governed Syria for decades” and urging other countries not to recognize them. More concerningly, regional newspapers have reported in recent days that the SDF is arresting men for allegedly dodging conscription in areas it controls, a clear signal of independence from the central government.

The SDF has denied the accusations, stating that its forces were conducting routine security operations. On Sunday, it claimed that seven of its members were wounded in drone attacks conducted by “militants of the Damascus government.” Rubin told TMD that, given its distrust of al-Sharaa’s government and the challenges facing Damascus, the SDF does not appear poised to relinquish much of its autonomy anytime soon. “For all practical purposes, the Kurds will try to outlast al-Sharaa,” he said.

But on Sunday at least, al-Sharaa attempted to project optimism that the elections represented a major step toward a modern Syrian state—one that included all the country’s inhabitants. “Building Syria is a collective mission, and all Syrians must contribute to it,” he said. However, it remains to be seen whether the former militant can accomplish that task through persuasion rather than force.