I recently went to the Netherlands to visit an old friend. He lives in Zeewolde, a small town (pop. 24,000) located in the Flevoland province. I found it remarkable that in this old country, the Netherlands, Zeewolde is only 42 years old, the province being included in 1986. In contrast, we spent an afternoon in Elburg, only about one kilometer on the other side of a little waterway from Flevoland, which was a Medieval fishing village with an impressive gate from 1392 that is still standing.

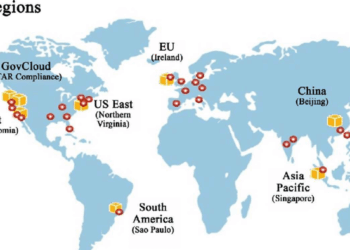

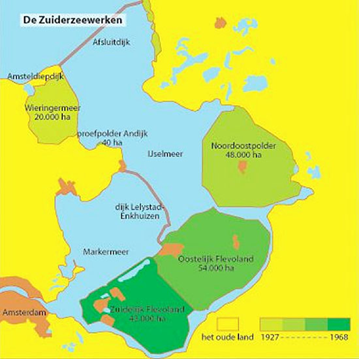

Flevoland. Zeewold is in the south, near the bottom of the image. Elburg is on the right-center, just outside of Flevoland, and Amsterdam is out of the image, just to the left on the AI.

The village gate of Elsburg.

This contrast exists because all 540 square miles of Flevoland are reclaimed territory, called polders, created by the Dutch for centuries. A short summary of the history of polder systems in The Netherlands is given below.

“The traditional polders in The Netherlands have been formed from the 12th century onwards, when people started creating arable land by draining delta swamps into nearby rivers. In the process, the drained peat started oxidizing, thus soil levels lowered, up to river water levels and lower. Throughout the centuries farmers have been adapting their agricultural system to lowering soil levels and occasional floods and invented new ways to organise themselves and keep sea and river water out – resulting in the building of hundreds of drainage windmills and later pumping stations to pump water from polders into the rivers and the sea. This development resulted in the creation of present-day polder landscapes that are characterised by grasslands on peaty soil with drainage channels, economically sustained by dairy farming, which harbour a rich flora and fauna. These systems function in a context of (among others) rising sea and river levels, continued lowering land levels, increasingly multifunctional use of land (urbanisation, recreation and tourism, nature conservation, culture conservation), interference of agricultural policies, and other interests. A plethora of government, non-government and private parties with intense negotiation practice make up the polder governance arena. The oldest of such organisations are the “water boards” with the mandate to provide safety from water threats for all citizens. The physical and institutional polder culture is indeed a crucial aspect of the Dutch national identity.”

Of course the Netherlands is famous for dams (or dikes). The Zuiderzee Works that eventually created Flevoland includes “the Afsluitdijk (enclosure dam), running from Den Oever on Wieringen to the village of Zurich in Friesland. It was to be 32 km long and 90 meters wide, rising to 7.25 meters above sea-level, with an incline of 25% on each side” that was completed in 1932. As an aside, the Wikipedia article on the Zuiderzee (South Sea) includes a short history of the “massive St. Lucia’s flood [that] occurred 14 December 1287, when the seawalls broke during a storm, killing approximately 50,000 to 80,000 people.” It destroyed “several dams and dunes and transform[ed] it into a bay which was then called the Zuiderzee, meaning Southern Sea.” What is stated without any notice of its political impact today is that a primary cause of the disaster was “rising sea levels due to global warming known as the Medieval Warm Period.”

The dams and polders around the Zuiderzee. The Afsluitdijk (enclosure dam) is at the top of the image.

In quaint Elsburg, we drank witte (also called wheat or white) beer in the warm Indian summer sunshine and talked about the current world situation. With images of Flevoland fresh in my mind, herein I describe my mixed perceptions. My host is an avid reader of LewRockwell.com. He is a pessimist. And as you readers can concur with him, there is a strong case for pessimism these days. With that in mind I thought of Flevoland itself, and the enormous size and duration of these projects, especially for such a small country. Today I can’t imagine any European country, or even the US, completing something similar today (for example, the California high speed train). Yet I remain optimistic. I could not disregard the tasty beer, the good looking people, and the charming village. In spite of my friend’s attitude, the Dutch seem to be a very prosperous and cheerful people. To understand the technical ability to create and maintain the polders impels one to have great admiration for this industrious country. How they came to endure the insipid Mark Rutte as prime minister for 14 years is a contradiction I leave for the Dutch to explain. A materialization of and symbol for me of the Dutch spirit of solidity and prosperity are the paving bricks and their patterns that make up virtually all of the sidewalks and many streets. To integrate these thoughts, I wonder why the “re” in reclamation is used to describe these projects. They created the land itself. While a real reclamation project would be to take back the culture of the West. I think it is possible, I think we must try.

Dutch paving bricks.

Just before this visit I had read Hope Against Hope: A Memoir by Nadezhda Mandelstam. She recounts her life with her husband, the poet Osip Mandelstam, in particular, during the Stalin induced Great Purge. In effect, Osip was arrested for poetry. After a period of internal exile with Nadezhda, he was sentenced to a forced labor camp. He subsequently died in a transit camp in 1938. She dedicated her life to preserving his poetry including memorizing much of it in the manner of Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. She lived isolated and in terror for many years. Finally, after Stalin’s death in 1953 she was able to lead a more normal life and to eventually write this memoir. In a late chapter titled Rebirth she wrote.

“I must admit to being an incorrigible optimist. Like those who believed at the beginning of this century that life had [emphasis in the original text] to be better than in the nineteenth century, I am now convinced that we will soon witness a complete resurgence of humane values. I mean this not only in respect to social justice, but also in cultural life and in everything else. Far from being shaken in my optimism by the bitter experience of the first half of this incredible century, I am encouraged to believe that all we have been through will have served to turn people against the idea, so tempting at first sight, that the end justifies the means and “everything is permitted.” M. [Osip Mandelstam] taught me to believe that history is a practical testing-ground for the ways of good and evil. We have tested the ways of evil. Will any of us want to revert to them? Isn’t it true that the voices among us speaking of conscience and good are growing stronger? I feel that we are at the threshold of new days, and I think I detect signs of a new attitude.”

If she could be an optimist after her experiences I can be optimistic too.