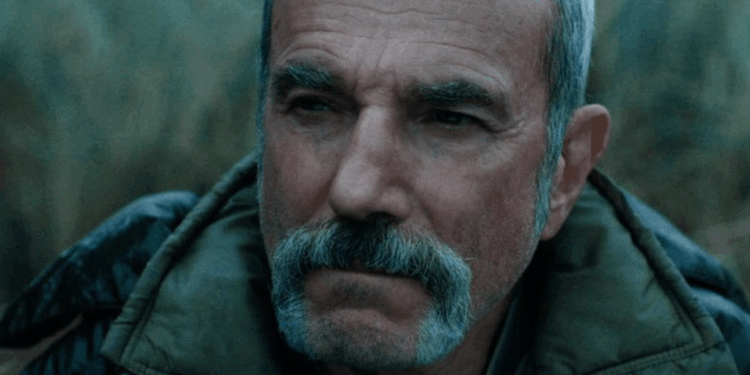

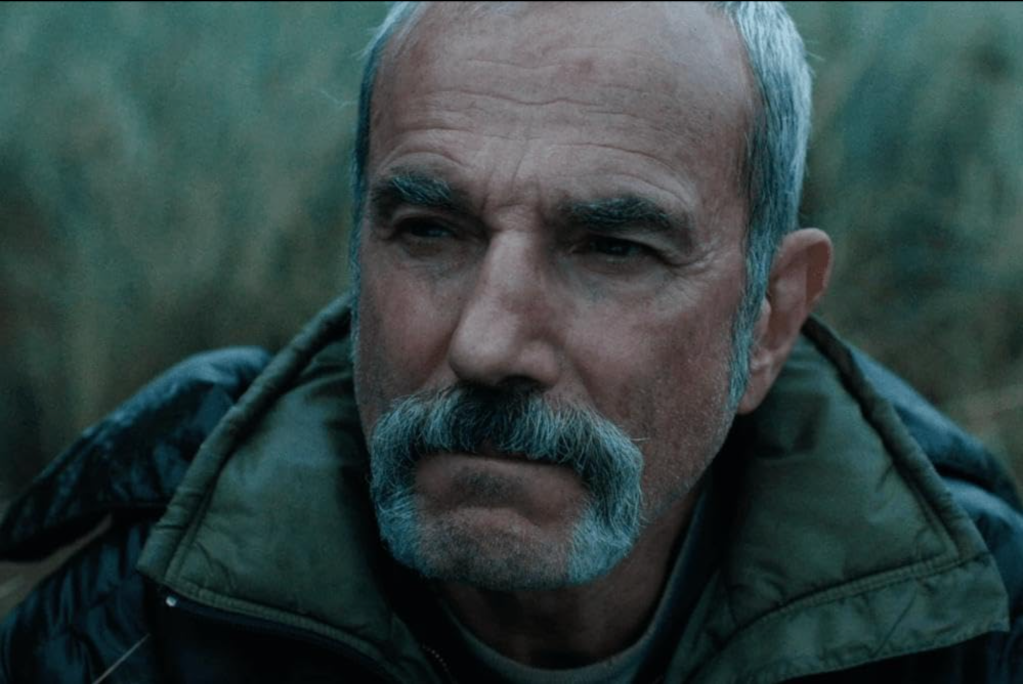

I felt like I just watched a graduate student’s final project when the credits rolled on Anemone. There was little dialogue, especially at the beginning, and most of the film relied heavily on acting giants—Daniel Day-Lewis, Samantha Morton, and Sean Bean—to make up for dialogue via expression and dramatic movement. The writing, which revealed a fraught history between father, son, and brother, was so drawn out that the few scenes that started to build suspense deflated, minute by minute.

But one of the most frustrating aspects of the movie is its approach to symbolism. Directed by Ronan Day-Lewis—Daniel Day-Lewis’ son—the film fails to capture the imagination it appears to desperately chase. Mystical elements are inserted throughout the film, but they rarely resonate with the narrative or dialogue. In one scene, Day-Lewis’ character, Ray Stoker—who secluded himself in the middle of a dense forest, leaving behind a wife and son due to a long-held secret gained during his time as a soldier in The Troubles—encounters a white, polar-bear-like spirit with a human-like face, which he perceives as his estranged son. After camping on a beach during a rainy day, Stoker is drawn by a white light to a lake, where the creature stands, its internal organs visible through transparent skin—a striking visual that, unfortunately, does little to convey emotional or narrative clarity.

During another scene, a dead fish about six feet long with what looks like chunks of skin taken out of its iridescent body floats by Stoker. Although earlier in the film Stoker reveals a traumatic story related to guts and gore, the scene itself does little to connect the plotlines together. The fish looks similar to a Japanese oarfish, and according to folklore, seeing an oarfish usually means an earthquake is coming—that is, certain doom and destruction. But in the movie, no such doom is shown.

The point of symbolism in film is to incorporate psychology and myth to give a story more depth. Beyond the immediate plot, what can this moment convey to the watcher? In Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan, the mirrors throughout the film—whether in the dance studio or the bathroom—symbolize introspection, vanity, and distortion. In Jordan Peele’s Us, the opening credit scene shows rabbits in cages, symbolizing a group of underground dwellers called the Tethered, doppelgangers created by humans that live strange and horrific lives that mirror those of their aboveground counterparts.

Contrast these to the opening scene of Anemone, where we see a child’s drawing go from depicting sweet visuals of home life to darker scenes of war. One wonders who exactly this is supposed to represent. Is it Ray Stoker’s son, with whom he has no relationship? Likely not, because later in the movie the mother explains what The Troubles are. Is it Ray Stoker? Doubtful, because he is a grown man.

One scene near the beginning does use symbolism quite well. Jem gives his brother a letter from Ray’s ex-wife, Nessa Stoker. The letter remains sitting on Ray’s windowsill, unread. A bit later, a human-sized doll, resembling Nessa, levitates over the edge of the bed. The lifeless body, more reminiscent of a specter than his ex-wife, gives the audience the haunting feeling of his past. Unfortunately, the rest of the film fails to live up to the sense of tension in this one scene, leaving movie-goers with a sense of dullness.

The title of the movie Anemone comes from flowers of the same name. Ray is out in his garden, tending to the flowers, when his brother, Jem, walks out and asks, “Are those the same flowers our father used to grow?” That’s it. One line as a nod to the flowers. One wonders whether the movie would be richer had there been any nod to the famous myth with which the flowers are most commonly associated—that of Aphrodite crying for her dying Adonis, her tears blossoming into anemones.

Day-Lewis’ acting is almost Shakespearean, with much of the plot revealed through long monologues. Although I personally didn’t find it entertaining, one cannot ignore the star’s talent in carrying the weight of the film. The music also at times seems to substitute for what the plot lacks, in the sense that it adds suspense.

Good acting and good music choices, though, cannot totally make up for subpar dialogue and narrative—and puzzling attempts at symbolism. Ronan Day-Lewis seems to understand the elements of what a movie needs, and what the audience demands—acting powerhouses, strong imagery, and a story that explores the human psyche—but fails to incorporate these elements in a cohesive manner. The artistry is there, the depth isn’t.