Authored by Antonio Graceffo via The Epoch Times,

After 12 years, Beijing’s four major defenses against the Belt and Road “debt trap” argument are dispelled.

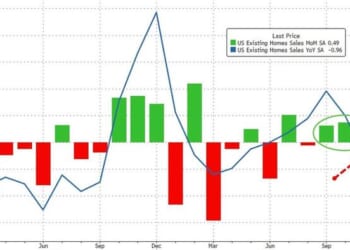

The 12th anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative (also called One Belt, One Road) was last month. Amid ongoing accusations that it is a debt trap, the Lowy Institute think tank reported that 75 developing nations now face severe debt crises driven by massive repayments to China. Developing countries are expected to pay Beijing a record $35 billion this year, $22 billion of which will come from the world’s poorest nations, forcing deep cuts to health, education, and essential services.

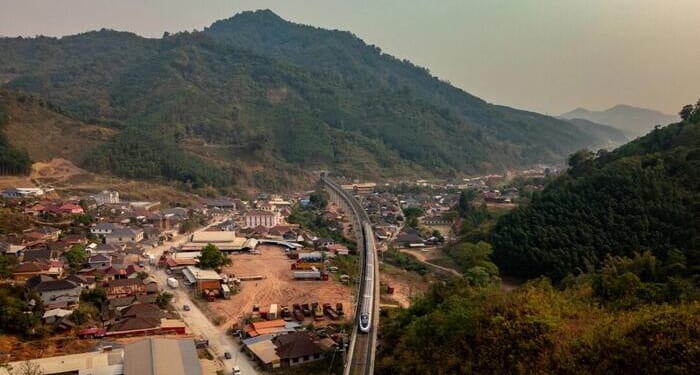

Launched in 2013, the BRI financed large-scale infrastructure projects across Asia, Africa, and Latin America through state-backed loans, making China the world’s largest bilateral creditor. Over the program’s first decade, roughly 80 percent of lending from the Chinese regime went to nations already in or near default. As these debts mature, repayment pressures are straining public finances and reinforcing the charge that Beijing deliberately created a global debt trap.

In its defense, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) advances four flawed arguments to deny that the BRI is a debt trap: first, that many developing countries owe more to Western lenders; second, that U.S. interest rate hikes caused their debt problems; third, that currency depreciation and a slowing global economy are to blame; and fourth, that China rarely seizes assets from countries unable to repay. Each of these claims collapses under scrutiny.

The CCP’s first defense—that many Belt and Road countries owe more to Western or international lenders than to China—is mathematically true in some cases but deeply misleading. While Chinese loans may represent less than half of a country’s total debt, these nations already had extremely low credit ratings and were considered too risky for traditional lenders. Western institutions stopped lending to avoid pushing them into default. China, however, stepped in and issued the very loans that tipped them over the edge. In many cases, Beijing became the lender of last resort because responsible lenders had walked away.

The second argument—that rising U.S. interest rates caused the debt crisis—is equally flawed. Fluctuating rates are a well-known risk built into every sovereign credit assessment. Countries that continue to borrow heavily despite poor ratings do so knowing refinancing will become more expensive when global rates rise. Responsible lenders account for that risk and withdraw when borrowers approach unsustainable levels of debt. China ignores those warnings, continuing to lend, ensuring that default becomes inevitable.

The third claim—blaming the crisis on currency depreciation and a slowing global economy—also collapses under scrutiny. Economic downturns and exchange-rate fluctuations are foreseeable risks that must be weighed before taking on debt. Many Belt and Road countries have weak, partially convertible currencies, but must repay their loans in U.S. dollars. As the dollar strengthens, debt service costs rise, draining national reserves and deepening economic distress. This is not the fault of the West, nor the result of U.S. monetary policy designed to harm others. The CCP’s reasoning is illogical, especially since most Belt and Road loans are themselves denominated in dollars.

The fourth argument used by the CCP against the “debt trap” accusation is that it rarely seizes assets from countries that cannot repay; instead, it claims to provide “debt relief” through refinancing or extending loans. In practice, this approach only deepens dependency. Beijing typically grants short-term restructuring, such as maturity extensions or grace periods, to low-income nations without reducing principal or easing interest rates.

It also relies on “rescue lending” mechanisms, including bridge loans from state banks, currency swap drawdowns through the People’s Bank of China, and commodity prepayment arrangements. These measures do not solve underlying solvency problems but merely postpone default, keeping borrowers afloat long enough to protect China’s own financial system.

A major study by AidData, the World Bank, Harvard Kennedy School, and the Kiel Institute found that by the end of 2021, China had carried out 128 bailout operations totaling $240 billion across 22 countries, marking a clear shift from infrastructure financing to emergency rescue loans. In 2010, less than 5 percent of China’s overseas lending went to distressed borrowers; by 2022, that figure had soared to 60 percent.

These bailouts also expose Beijing’s hypocrisy: while the CCP accuses the West of predatory interest rates, the average Chinese rescue loan carries an interest rate of about 5 percent, more than double the IMF’s standard 2 percent. As of Oct. 1, 2025, despite higher U.S. interest rates, the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights lending rate stands at only 3.41 percent, still significantly lower than what China charges struggling nations for so-called relief.

The true scale of Belt and Road debt may be far worse than official data suggest. To shield its own banking system, the Chinese regime increasingly uses the People’s Bank of China’s global swap-line network, which has provided more than $170 billion in short-term liquidity to foreign central banks. These loans, often labeled as “temporary,” are routinely rolled over for years, allowing governments to conceal their true debt exposure since international reporting rules exclude short-term liabilities.

This practice has created vast “hidden debts,” estimated at roughly $385 billion by AidData in 2021, and the figure is likely far higher today, as more loans come due and few have been repaid in the intervening years.

The CCP’s opaque bailout strategy—designed to protect its lenders rather than assist struggling nations—ensures that the full weight of Belt and Road debt remains concealed from public view.

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times or ZeroHedge.

Loading recommendations…