You’re reading Dispatch Faith, our weekly newsletter reporting on the biggest stories in religion and faith. Looking for more ways to support our work? Become a Dispatch member today.

Since his papacy began in May, Pope Leo XIV has had a mostly warm reception among faithful Catholics and church-watchers. That came to an end for some in recent weeks, following remarks Leo made about a host of hot-button issues and after issueing his first apostolic exhortation, Dilexi Te.

For Dispatch Faith today, Dan Hugger argues that when such controversies arise, there are helpful ways to scrutinize statements and teaching of the head of the Catholic Church. And—surprise!—they probably don’t gel well with the world of clickbait and conflict entrepreneurialism.

Dan Hugger: How to Question a Pope

On May 15, 1961, Pope St. John XXII promulgated a social encyclical on Christianity and social progress titled Mater et Magistra. The pope endeavored to further develop and extend the tradition of modern Catholic social teaching inaugurated by Pope Leo XIII in his social encyclical Rerum Novarum 70 years earlier. Such encyclicals by 1961 were part of a venerable tradition to which every succeeding pope had made contributions. The opening paragraph of Mater et Magistra explains both the encyclical’s title and the nature of the tradition of which it is a part:

Mother and Teacher of all nations—such is the Catholic Church in the mind of her Founder, Jesus Christ; to hold the world in an embrace of love, that men, in every age, should find in her their own completeness in a higher order of living, and their ultimate salvation. She is “the pillar and ground of the truth.” To her was entrusted by her holy Founder the twofold task of giving life to her children and of teaching them and guiding them—both as individuals and as nations—with maternal care. Great is their dignity, a dignity which she has always guarded most zealously and held in the highest esteem.

In the world of the early 1960s, the church’s social teaching was not criticized or dismissed lightly, especially by Roman Catholics. When Priscilla Buckley, elder sister of William F. Buckley Jr. and then managing editor of National Review, concluded her August 12, 1961, “For the Record” column with the stray observation, “Going the rounds in Catholic conservative circles: ‘Mater si, magistra no’” (Mother yes, teacher no), the magazine received torrents of criticism. In an interview more than 40 years later she was asked if she had any editorial regrets and replied, “I had belated second thoughts about the wisdom of republishing a quip of Garry Wills’s … ‘Mater si, Magistra no,’ in response to a papal encyclical that got us into lots and lots of trouble with the liberal Catholic press over lots and lots of years.”

In 1961, a single sly, macaronic phrase playing off the Cuban dissident slogan “Cuba sí, Castro no” could hurt a magazine’s credibility among Catholics for decades. Papal criticism by Catholics is now its own cottage industry, as any Catholic who has spent any time on the internet over the past month has seen vividly demonstrated. The near-universal adoration and acclaim that greeted Pope Leo XIV in the aftermath of his election in May has given way to pointed criticism, much of it intemperate, as he has addressed controversies around hot-button political issues like the death penalty, abortion, migration, and poverty.

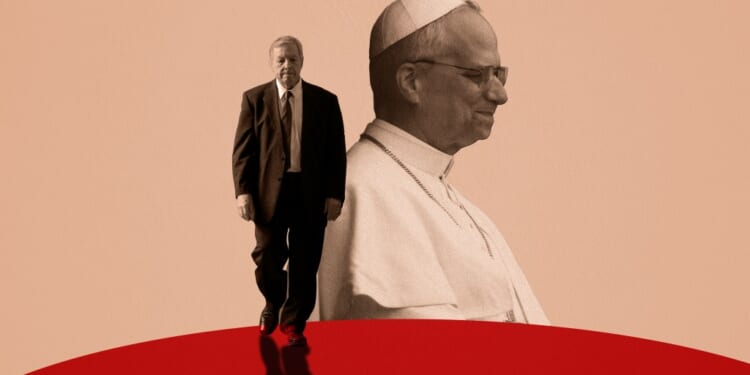

The catalyst for the latest controversy and criticisms was, uncannily enough for a pope hailing from the Windy City, the Archdiocese of Chicago. The diocese had planned to present retiring Illinois Sen. Dick Durbin with a lifetime achievement award for his work on migration issues in November. Durbin is Catholic and has been supportive of the church’s work on behalf of migrants. He is also a supporter of abortion rights and is currently prohibited from receiving the Eucharist in the Diocese of Springfield, where he resides. Springfield Bishop Thomas J. Paprocki expressed his shock at the planned award in comments to The Pillar published on September 20:

Given Senator Durbin’s long and consistent record of supporting legal abortion — including opposing legislation to protect children who survive failed abortions — this decision risks causing grave scandal, confusing the faithful about the Church’s unequivocal teaching on the sanctity of human life.

Cardinal Blase J. Cupich, archbishop of Chicago, responded to criticism in a statement issued on September 22, claiming that, “Senator Durbin informed me some years ago that he had purchased a condo in Chicago, registered in a parish of the archdiocese and considers me to be his bishop,” and argued that:

At the heart of the consistent ethic of life is the recognition that Catholic teaching on life and dignity cannot be reduced to a single issue, even an issue as important as abortion. The annual celebration of immigrants, Keep Hope Alive, will recognize all the critically important contributions Senator Durbin has taken to advance Catholic social teaching in the areas of immigration, the care of the poor, Laudato Si’, and world peace.

The identity of Durbin’s bishop is surely known to the Lord but is best left to canon lawyers to discern. More than half a dozen other bishops in the U.S. made criticisms of the planned award.

The debate reached the pope at Castel Gandolfo by the end of September where he received a question about it from EWTN News. He answered that while he was not familiar with the particulars of the case:

I think it’s important to look at the overall work that a senator has done during, if I’m not mistaken, in 40 years of service in the United States Senate.

I understand the difficulty and the tensions. But … it’s important to look at many issues that are related to the teachings of the Church.

Someone who says I’m against abortion but is in favor of the death penalty is not really pro-life. Someone who says I’m against abortion but I’m in agreement with the inhuman treatment of immigrants in the United States, I don’t know if that’s pro-life. … The Church teaching on each one of those issues is very clear.

Pope Leo XIV’s foray into the controversy occurred the same day Cardinal Cupich announced that Durbin decided to decline the award. Perhaps the controversy having reached the pope’s attention caused Durbin to decline, or perhaps his decision was made before. Either way, the pope’s remarks gave new legs to the controversy.

The chair of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Committee on Pro-Life Activities, Bishop Daniel E. Thomas of the Diocese of Toledo, reiterated Pope Leo’s concluding statement that the church’s teaching is very clear but then called attention to “a hierarchy of truths” within that teaching:

There’s no question that people across the board are vulnerable, but who are the most vulnerable? Those are the innocent and completely vulnerable little children in the womb who cannot defend themselves. So, you know, if you are for immigration, that’s one thing. But if you are promoting the protection and the promotion of direct killing of infants in the womb, I would say that that’s a very grave matter.

Others were less judicious and charitable in their engagement with the pope’s response to the Durbin kerfuffle, with a similar pattern of reaction following the release earlier this month of Pope Leo’s first apostolic exhortation, Dilexi Te, in which he called on all Christians to see Christ in the poor among us, embrace a more holistic understanding of poverty, welcome migrants, and embrace almsgiving.

The Lord commands us to “[h]onor your father and mother. Then you will live a long, full life in the land the Lord your God is giving you” (Exodus 20:12) and to “[o]bey your spiritual leaders, and do what they say. Their work is to watch over your souls, and they are accountable to God. Give them reason to do this with joy and not with sorrow. That would certainly not be for your benefit” (Hebrews 13:17). It can, however, be difficult for believers to listen to religious leaders when they address hot-button political issues like the death penalty, abortion, migration, and poverty. It is especially difficult if we have strong opinions or independent expertise. How can we be dutiful children and earnest students of religious authorities whom God has appointed to bring us spiritual life and earthly guidance?

The first step is listening. It is easy to devalue and dismiss teaching from religious leaders by placing them in opposition to earlier religious teaching within the tradition. This is often done today with the church’s teaching on the death penalty. As stated in The Catechism of the Catholic Church, “[T]he death penalty is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person.” Critics of this teaching note that from the days of Noah (Genesis 9:6) until the mid-20th century, recourse to the death penalty by legitimate authority was held to be licit in order to safeguard the common good. The Catechism itself argues that the current teaching is not merely a rearticulation of what came before but an organic development of doctrine. The grounds for this development are “an increasing awareness that the dignity of the person is not lost even after the commission of very serious crimes,” the emergence of a new understanding “of the significance of penal sanctions imposed by the state,” and the development of more effective systems of detention that “ensure the due protection of citizens but, at the same time, do not definitively deprive the guilty of the possibility of redemption.” Catholics must earnestly wrestle with this account of development rather than casually dismiss it.

Listening can be difficult when contemporary religious leaders themselves disagree, as the bishops involved in the Durbin dust-up certainly appear to! During such cacophonies we must listen with greater concentration to hear a deeper underlying understanding. Bishop Thomas’ response to this quandary of invoking the concept of “a hierarchy of truths” to understand Pope Leo charitably is an example of how the church has always sought to reconcile apparent contraries, by making careful distinctions.

When religious leaders go against the grain of powerful political trends, such as Pope Leo’s strong stance against the worldwide backlash against migrants, we must seek to quiet our own passions so we can hear the teaching with dispassion and openness removed from the polarized framing of populist politics and resistance.

Listening is only the first step, and even the conscientious children and dutiful students can struggle to understand and affirm, let alone live out the church’s social teachings.

New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, after reading and reflecting on Dilexi Te, wishes it was less general and more concrete in its policy prescriptions. While recognizing that the church is not a policy shop, he hopes for a more constructive engagement with the challenges posed by demographic strains experienced by mature 21st century welfare states in Europe and North America.

Others, such as my colleagues John C. Pinheiro and Caleb Whitmer, after reading and reflecting on Dilexi Te, wish the pope’s language around the economy were less concrete. Often the language in Dilexi Te around “the economy” makes it appear as if markets are a single monolithic, impersonal, and malevolent force. The understanding of economists is different. Markets are complex, personal, and positive-sum. The pope’s rich and holistic understanding of the complex and multilayered nature of poverty is strikingly different and clearly informed by the social sciences. The greatest service the poor, as he encourages throughout the exhortation, is to bring them from the margins to the center of our economic, social, and spiritual life.

The newest doctor of the church, St. John Henry Newman, taught that the church should not fear constructive engagement with its teaching, “for all branches of knowledge are connected together because the subject matter of knowledge is intimately united in itself, as being the acts and work of the creator.”

Pope Leo’s response when questioned about the Durbin affair outside Castle Gandolfo contained great wisdom about how constructive engagement with the church’s teaching should proceed:

So they are very complex issues and I don’t know if anyone has all the truth on them, but I would ask first and foremost that they would have respect for one another and that we search together. … And to find the way forward as a Church.

The church is both mother and teacher, deserving of love and respect, but she is also an endless reservoir of patience and eager for sincere questions.

Isaac Wood: ‘If You’re Hungry, We’ll Feed You’

It’s been more than a year since Hurricane Helene careened into the South and ravaged much of the Appalachian region. On the site today, Isaac Wood chronicles how churches in one town have continued to step up to aid their communities, a story that has played out in multiple places.

Churches helped fill the gap. One of them was Valley Hope Church, a Presbyterian church only three minutes from the Alan Campos neighborhood. Down a hill from Valley Hope is a creek that shoots off from the Swannanoa River. During the hurricane, its banks overflowed. About 50 yards from Valley Hope, a Spanish-speaking couple and their three kids were in their house when the creek flooded. Water filled their entire first floor, trapping them on their balcony.

Neighbors helped the kids escape with a rope, throwing it to them and pulling them across the rushing river. But the current was relentless, and the mother was swept away. Her husband swam after her. They caught themselves on shipping containers that had washed into the creekbed, and neighbors helped them to dry land from there.

“We’ve gotten to know them,” said Valley Hope pastor Anthony Rodriguez. “We helped take care of their house.” Once the storm abated, the Valley Hope congregation quickly decided to focus on helping others near the church. “God has put us here in this neighborhood,” Rodriguez said, “and we want to make sure our neighbors, on this street, have food, water, and whatever they need for sanitation.”

Pieter Valk: Sloppy Laws Risk Silencing Good Therapy

Last week the Supreme Court heard a case that could either uphold or overturn a Colorado law making illegal so-called “conversion therapy.” The problem with the law, according to Pieter Valk, who opposes conversion therapy after having gone through it himself, is that if it stands, it can (and probably will) be abused to restrict good, faith-based therapy. On the site today, he argues:

The problem is syntactic as much as substantive. In the Colorado definition, the phrase that follows including (“efforts to change behaviors or gender expressions … ”) is grammatically ambiguous. In linguistic terms, it’s unclear whether including is used illustratively (banning only practices meant to change orientation) or definitionally (making behavior/identity change themselves count as conversion therapy, regardless of purpose). Depending on how one reads that single word, the Colorado statute could either narrowly target orientation-change efforts or broadly penalize ordinary Christian therapy.

Colorado’s solicitor general, defending the law before the Supreme Court last week, insisted it “only bans performing a treatment that seeks the predetermined outcome of changing a minor’s sexual orientation or gender identity” and “does not stop a professional from expressing any viewpoint.” But as Justice Alito replied, “I don’t see that limitation in the text of the statute. The statute says ‘including efforts to change behaviors or gender expressions.’ So why isn’t that broader than what you’re describing?” The law’s plain language could easily be read to make those behaviors themselves sanctionable, regardless of intent.

More Sunday Reads

- Last week Chinese authorities carried out a crackdown on several house churches there, arresting more than two dozen pastors and church staffers, including influential Zion Church pastor Jin “Ezra” Mingri. Angela Lu Fulton reports on the arrests in Christianity Today: “The government began threatening to close the church in August 2018 after Jin refused to install security cameras in the sanctuary. Authorities pressured about 100 church members to stop attending. In September, the government officially banned the church, sealing off the church property. Police detained Jin and other leaders for a few hours before releasing them. This week’s roundup was different, said Sean Long, a Zion pastor pursuing a doctorate in theology at Wheaton College. In a coordinated attack, police in cities around the country carried warrants to detain the leaders and staff. They face charges of ‘illegal dissemination of religious information via the internet,’ Long said. Yet Long noted that Jin had long anticipated a crackdown. In 2018, even before the church was shut down, Jin sensed persecution coming and sent Long and his family abroad so an arrest of pastors would not leave the church leaderless. Jin’s wife, daughter, and two sons also moved to the US so the government could not use them as leverage. This year Jin again sensed a storm coming.”

- Have you ever wondered how the Catholic Church tracks particular feast days for particular saints, and what happens when multiple feasts fall on the same day? For The Pillar, Michelle La Rosa interviewed canon law professor Father James Bradley to find out: “There can be overlapping feasts. And not all of those who have been canonized are actually celebrated in most places. Most days have multiple saints, and it might depend on a number of factors as to whether or not you ever celebrate them. They’re all recorded in what’s called the Roman Martyrology. That book, it has a record, basically, of every blessed and saint in the life of the Church, and if you turn to a page of that, you’ll see sometimes 20 or 30 saints. Some of them will be kept universally, because they’ve been included in the universal calendar, which we call the General Roman Calendar, and others will be kept locally. So you might find that there are saints that are celebrated in France or in England or in India or in Australia which are local to there, but are not celebrated elsewhere. Each nation has a national calendar, and then each diocese and each religious order also has a particular or proper calendar, and that’s for them. Countries in Europe and elsewhere have got saints going back 2,000 years. In England there’s a huge number of Anglo-Saxon saints that most people have never heard of, and they’re not even kept in the national calendar in England, because the national calendar is itself quite full. So you might even find a local saint who’s kept in one diocese, but not in all the others, because they were the bishop of that diocese, for instance. So they’re kept there, but they’re not necessarily kept everywhere.”

Religion in an Image