You’re reading Capitolism, Scott Lincicome’s weekly newsletter on economics. This edition has been unlocked for all readers. If you’d like to support more of our work, you can become a Dispatch member today.

As the federal government shutdown enjoys its third week with no end in sight, Americans are being treated to a common Washington spectacle: breathless media coverage of offline government services, furloughed workers, and rising economic costs—as politicians from both parties fight over who’s to blame (spoiler: the other guy). If you’ve seen more than one shutdown—and, unless you’re in grade school, you have—you know the script well.

Of course, as with any good dramatic series, certain characters and plotlines change with each episode. This time around, there are new wrinkles about possible mass firings (some already walked back), and the shutdown’s MacGuffin is billions in “temporary” Obamacare subsidies that were enacted during the pandemic. Overall, however, it’s pretty standard stuff. Most of the government is actually open, and the drama will almost certainly end like it always does: with an agreement no one likes, with both sides claiming victory, and with little long-term damage to the government or the economy.This reality doesn’t mean, however, that the shutdown is meaningless. Besides the real effects on certain people (especially certain government workers), the shutdown also reveals some serious, structural problems in how Washington operates—problems that neither party seems willing or eager to fix, or even acknowledge. That’s the real shutdown story, not shuttered museums, delayed passport applications, or even the contentious government program at the root of it all.

The Government Isn’t Really ‘Shut Down’

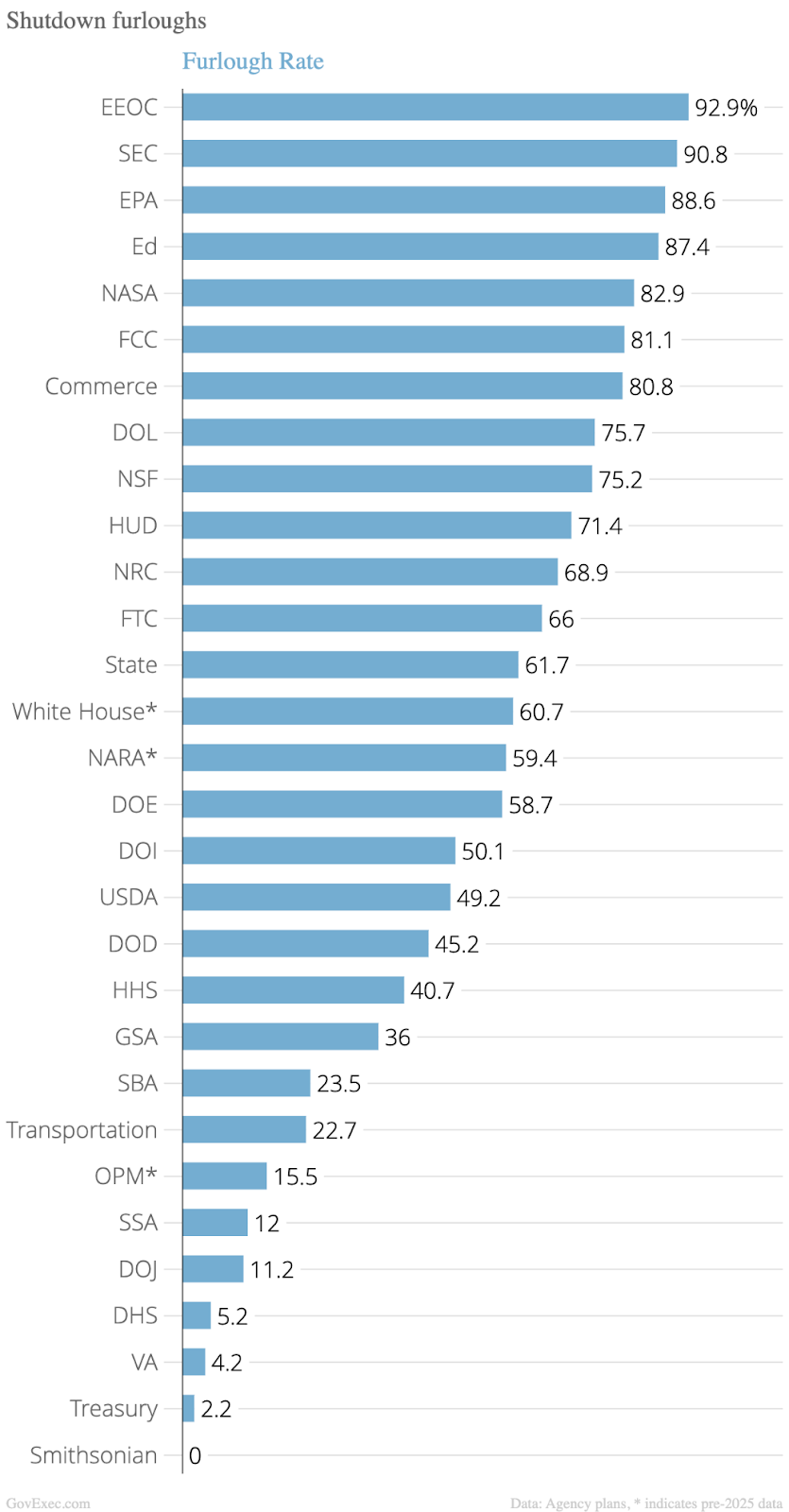

Before we get to that, however, let’s review just how much—or, more accurately, how little—of the federal government is actually shut down. First, the vast majority of the federal workforce is still working. According to the Trump administration’s shutdown contingency plans for executive branch agencies, around 25 percent of federal workers—approximately 547,000 of 2.1 million—were initially furloughed. Since then, the number has climbed to more than 610,000, but that’s still just around 29 percent:

As the folks at Government Executive explain, the administration has wide latitude to determine who stays or goes during a shutdown, and Trump officials actually erred on “stay” side a little bit more than did previous administrations during recent shutdowns—and not just at the Department of Homeland Security.

The White House, through the Office of Management and Budget, maintains some latitude in the exact consequences of a shutdown. Federal employees funded through mechanisms other than annual appropriations, as well as those necessary to protect life and property, are considered either “exempted” or “excepted” and work throughout shutdowns on only the promise of backpay …

Most of the change stems from two agencies: in a shutdown this week, the Trump administration would allow the entire Internal Revenue Service to continue working using funds provided in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. In preparation for a potential funding lapse in 2024, the Biden administration had planned to furlough more than half of the agency. The Defense Department on Wednesday would send home around 45% of its 741,000 civilian employees. In 2024, the Pentagon would have furloughed more than 100,000 additional workers.

More furloughs could come if the shutdown drags on, but Government Executive also notes that some workers could get called back. Regardless, it adds that “following the record-setting 35-day shutdown in 2018 and 2019,” workers who are sent home are guaranteed back pay via the Government Employee Fair Treatment Act of 2019. Surely, delayed paychecks can create genuine hardship for some government workers, but this clearly isn’t the halt to government that the term “shutdown” implies.

More importantly, virtually all core government operations continue uninterrupted—and many other services are still being provided. All active-duty military personnel, for example, continue to perform their duties (with the Trump administration controversially paying them through supposedly leftover Pentagon funds—something we will get back to in a moment). Law enforcement agencies—the FBI, CIA, Drug Enforcement Administration, and Coast Guard—all continue operating. Border protection, in-hospital medical care, power grid maintenance, wildfire and disaster response, weather forecasts, air traffic control, TSA, and other infrastructure and/or safety-related government operations are also proceeding as normal—again, with back pay assured for the workers involved.

Mandatory spending programs—Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid—are also still (mostly) running because they’re funded through permanent authorizations and thus operate independently of the congressional appropriations process now stymied by the political impasse. Other programs that might eventually stop, such as SNAP and WIC, also have continued because the executive branch tapped into leftover or reserve funds. (States might also step in should that funding eventually run dry.) The U.S. Postal Service is also unaffected because it’s funded through its own revenue from services and products, not congressional appropriations—another point we’ll return to shortly.

So, what has shut down? As this useful agency-by-agency review from the New York Times shows, it’s been frivolous stuff like the Smithsonian Institution, which just closed its museums after limited carryover funding ran out; certain government research projects and investigations; processing of new applications for government services, permits, and awards (grants, loans, contracts, etc.); and the dissemination of some government statistics. Heck, even the national parks—long a political bargaining chip during shutdowns—are still open to visitors, though with limited services and maintenance.

These disruptions are annoying, even costly for some Americans, but the overall patchwork of workers and operations reveals a government that’s not “shut down” in any meaningful sense. Instead, almost everything almost everyone thinks of as a standard “government service” is still up and running, albeit sometimes in a less efficient way. (Insert government efficiency joke here.) And most of the offline services and workers will pick right back up where they left off when the shutdown ends. (Meanwhile, President Donald Trump is running around the world like nothing’s even happening back home.)

In short, the vast machinery of our federal government continues to crank—even when it’s “shut down.”

The Economic Hit Is Trivial

This helps to explain why government shutdowns tend to have small economic effects over the medium to long term. For example, the Congressional Budget Office’s analysis of the 35-day shutdown in 2019 documented that the result was almost entirely a deferral of economic activity, not a permanent economic loss. As CBO explained, the shutdown did have some immediate economic effects—mainly reduced demand in the private sector resulting from reduced consumer spending by federal workers who missed paychecks. However, this “dampening of economic output” was “reversed once people returned to work.” Federal workers got their back pay and resumed spending, government operations resumed, and related bottlenecks in the private sector unclogged. During the shutdown, moreover, Americans substituted away from certain government services that were offline or simply changed their plans. As CBO noted, for example, “losses in tourism activity due to closures of national parks and museums may be offset if tourists choose alternative destinations or activities or may be recovered if tourists reschedule their visits.”

Overall, CBO found that only about $3 billion was permanently lost during the five-week shutdown. That was the equivalent of about 0.02 percent of U.S. GDP that year—insignificant for an economy that grows 2 to 3 percent each year. Research from previous shutdowns shows similar patterns (and creative ways furloughed workers avoided debt and credit problems at little to no cost), and CBO wrote last week that it expects the same this time around.

This isn’t to say shutdowns are entirely costless. Along with that $3 billion in GDP losses, delayed government approvals, permits, and awards can create problems for the parties involved. Uncertainty can impede business planning, and thousands of federal workers face real financial stress. It’s also less than ideal—as we’ve discussed—that some government economic statistics have gone missing (though other data are still getting published and private entities are stepping in to fill some gaps). And more harms could materialize if the shutdown lasts an abnormally long time and reserve/stopgap funding dries up.

As a macroeconomic matter, however, the shutdown’s impact has thus far been typically negligible—regardless of what bickering partisans and cable news pundits might suggest. And, of course, the vast majority of the private economy continues to chug right along. (Lessons abound.)

The Real Problems the Shutdown Reveals

This reality check matters because politicians on both sides of the aisle routinely weaponize shutdown hysteria to score cheap political points and to avoid harder policy conversations that the shutdown reveals they should be having.

First, the shutdown raises an obvious question about why government services that are shut down are still beholden to the whims of the annual appropriations process when they could instead be self-funded or separated from the government entirely. As noted, the Postal Service doesn’t shut down during budget impasses precisely because it operates on this model. The same goes for the State Department’s passport services, FDA reviews of drug and other applications, and a few other government services. As a result, they’re far more insulated from politics than most other services—including ones that really should be.

The clearest example is air traffic control, which is supposedly open but now struggling. As we’ve discussed, the U.S. is virtually alone among developed nations in funding its ATC system through general revenues. Yet, as Reason’s Bob Poole explains, this approach comes with real costs, including during government shutdowns when ATC is supposed to still be up and running:

As this article is being written, the federal government shutdown is dragging on, and reports of overstressed controllers taking sick leave are reflected in late arrivals and departures at more and more airports (following the ‘air traffic control zero” event at Hollywood Burbank Airport on Oct. 6, when there were zero controllers in the tower on the evening shift).

The tragic aspect of this fiasco is that it could not have happened in 98 countries that, since 1987, have depoliticized their air traffic control systems by taking them out of the government budget and converting them into user-funded public utilities (analogous to toll roads and electric and water utilities). New Zealand was the first, spinning off its air traffic control (ATC) system as Airways New Zealand, and transferring the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO)-compliant weight-distance ATC fees so that instead of being paid to the New Zealand government, they were paid directly to Airways. And since aviation is a growing industry, that revenue stream became bondable, making it possible to long-term finance ATC modernization, of both technology and facilities.

[These ATC programs] are outside their governments’ budget and hence not affected by their governments’ fiscal problems. Our airlines, passengers, and air traffic controllers would be spared the present miseries if Congress were to depoliticize our Air Traffic Organization (ATO) by separating it from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and enabling it to charge ICAO-compliant user fees and issue revenue bonds based on that revenue stream.

Other U.S. government services where beneficiaries can be identified and charged should be similarly reformed—especially things like parks and museums that could easily operate based on a combination of fees, merchandise/event sales, and private donations. (Privatizing them entirely would be even better, but I’m happy to start small.) Doing so would create better incentives, more stable funding, and greater insulation from political theater. Until the current and dysfunctional funding model changes, disruptions will persist—and, in the case of things like air traffic control, the costs could be a lot bigger than a lost day at the park.

The next and perhaps most troubling problem this shutdown reveals isn’t what’s closed, but what remains open—and how. In particular, the Trump administration has found ways to continue funding its political priorities without actual congressional appropriation, revealing the extent to which the executive branch has unilaterally claimed spending powers that should reside with Congress. Most notably, Trump announced his administration had “identified funds” to pay military service members on schedule, directing the defense secretary to ensure October 15 paychecks went out. The FBI also got paid in a similarly dubious way.

These and similar moves are undoubtedly politically popular—few want to see active duty military go unpaid—but they represent a dramatic expansion of executive power over the federal purse. And, as our own Chris Stirewalt recently explained, the seeds of this expansion were planted years ago when President Obama kept Obamacare afloat via “a kind of slush fund in the Treasury Department to pay subsidies to insurance companies that hadn’t been included in the original legislation passed by Democrats alone four years earlier.” Because the lawsuit challenging Obama’s ploy died, Obamacare lived, and the door to ever-greater executive abuse was opened:

One president got away with making his own laws, and future presidents have indeed done the same. In the current funding fight, the power of Congress is to inflict pain by refusing to appropriate funds. And on the list of pain points in a shutdown, none surpass the troops going unpaid. But by quiet, bipartisan assent, that’s being taken off the table as the president just moves some money around to make payroll. Just add that to the list of laws the president either just ignores or skirts, from the unilateral declaration of war against drug cartels to the TikTok ban.

Unfortunately, Politico reports, the parties’ acquiescence to this presidential lawmaking continues today, with congressional Republicans upset—but silent—about Trump’s spending moves during the shutdown. Until this dynamic changes—until Congress gets back in the game by blocking illegal funding moves and passing appropriations bills individually and on time—we should expect future presidents to take even more license to go on shutdown spending sprees without legislative approval. As a result, the constitutional separation of powers will weaken even further.

Finally, as Romina Boccia of the Cato Institute notes, current bickering over a few billion dollars in disputed health care spending distracts from the massive fiscal crisis almost everyone in Washington created yet still refuses to acknowledge. Federal spending in Fiscal Year 2025 exceeded $7 trillion for the first time ever—a $275 billion increase over last year. The deficit is $1.8 trillion; total debt is $38 trillion; and, as a share of U.S. GDP, the debt will exceed its postwar high in 2029 and then just keep on climbing from there. Interest on that debt hit $1.2 trillion—roughly 17 percent of total spending in FY2025 and, Boccia notes, more than total spending on national defense. She adds that interest will consume more than a quarter of all federal revenue within the decade—trillions that must be taken from American taxpayers and that can’t be spent on anything else.

As AEI’s Michael Strain explains, the enhanced Obamacare subsidies that ostensibly caused the current shutdown were “designed as a temporary measure to soften the blow of the pandemic,” originally scheduled to expire in 2022, and should be allowed to expire today because they give billions to middle- and upper-middle-class families who don’t need government assistance (yes, including these folks). At $35 billion per year, however, their cost is a mere rounding error when compared to even the interest on the federal debt, yet Strain predicts that they’ll be extended again—proving again that the impasse is far more about political messaging and point-scoring than actual fiscal discipline.

Summing It All Up

The current government shutdown matters, but not because of temporary inconveniences that will be resolved when Congress strikes a deal, as it always does. It matters because the shutdown reveals a fundamentally broken Washington, where services are needlessly funded by annual political fights rather than sustainable revenues, an executive branch—thanks to cowardly legislators—claims ever-greater authority to spend taxpayer money without congressional approval, and a political class—in both parties—would rather engage in budget theater than address the nation’s unsustainable fiscal trajectory.

Until we fix these structural problems, we’ll keep having shutdowns—and keep missing the point. The only bright side is that hardly anyone in the real economy seems to have even noticed the government is shut down at all.

Chart(s) of the Week