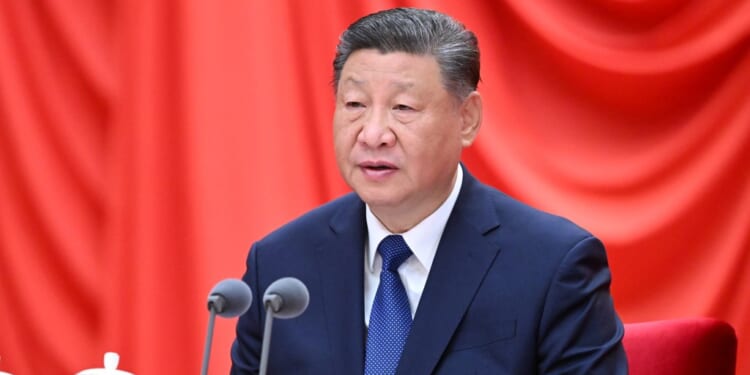

According to Rana Mitter, a historian of modern China and the S.T. Lee Chair in U.S.-Asia Relations at Harvard University’s Kennedy School, the military purge might also bring one of the more independent parts of China’s governing apparatus to heel. “[Xi] has done a pretty successful job of making sure that the governmental structures are essentially there to do his bidding,” Mitter told TMD. “[But] there is a sense that the PLA and the structures there may not have been as completely under control as the civilian elements.”

In China’s one-party state, the government and the Party apparatus are essentially parallel structures—but the Party has always been the senior partner, charged with supervising the state’s ideological direction. Under Xi’s immediate predecessors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, factions called “cliques” held more power, and the state was at least nominally distinct from the Party. “What Xi Jinping has done over the last 12 years is to make that distinction almost meaningless,” Mitter said. “Essentially, to put party domination directly and fairly explicitly above any state structures.”

Multiple fired officers were members of the “Fujian clique,” which had previously been among Xi’s most powerful backers. But Xi clearly no longer needs their support.

As China develops from a middle-income to a high-income country—which means rising above a Gross National Income of $14,000 per person, a goal expected to be achieved within the next few years—the Party is confronting a trade-off between encouraging top-down technological development and fostering a robust consumer economy.

“We’re going to see China double down on depending on technology to help drive growth,” Scott Kennedy, the trustee chair in Chinese Business and Economics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told TMD. The official communique from the plenum, published by the state-run Xinhua News Agency on Thursday, stressed the development of “new productive forces,” as in high technology, for the next five years.

China has already constructed much of its national economic strategy around high-tech manufacturing. It’s the world’s largest producer of solar panels and electric cars, and earlier this year, Chinese planners announced a list of new technologies for future development, including hydrogen energy, robotics, and quantum computing.

“Chinese leadership believes that its economic and security future depends on tech,” Kennedy said. Recent efforts by the U.S. to block China’s rise in frontier technologies—most notably, bans on advanced semiconductor chips used in AI development—have only strengthened the CCP leadership’s conviction that China needs greater economic self-reliance.

“I think they have now realized that the U.S. is determined to slow China’s growth,” Tianlei Huang, a research fellow and China Program coordinator at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, told TMD. “That’s why they have to be self-sufficient, not just in terms of technology, actually, but also in terms of energy and food.” China’s support for Russia in Ukraine, he argued, is at least partly due to its desire to maintain access to Russian energy and food exports, as an alternative to the U.S., which remains a major exporter of food, such as pork, to China.

The impulse toward self-sufficiency has deep roots. Ever since the Communist Party’s victory in the Chinese Civil War in 1949, China’s leaders have been doggedly focused on avoiding another “century of humiliation,” the term used to describe the country’s domination by Europe and America from 1839 to 1945. The self-strengthening movement, an effort during the late-19th century to modernize China’s military and government, was a famous failure, not least because the Chinese Empire was reliant on imports of modern Western weaponry, which could be cut off at will. Xi refuses to risk the same dependency with batteries and semiconductors.

But the drive to self-reliance has trade-offs. China is an increasingly wealthy nation, but one plagued by entrenched poverty and deep inequality. In 2021, roughly 17 percent of the population was still living below the World Bank’s poverty line of $6.85 a day. Rural poverty is still common, and Huang noted that more than 300 million Chinese citizens are migrant laborers, often shut out from place-based health care and employment benefits.

Every dollar spent on manufacturing, then, is a dollar not spent on fortifying the country’s still-meager social security system, adapting health care to the needs of a rapidly aging population, or providing child care support. Many economists have highlighted the need for China to continue developing its consumer market by increasing disposable income; expanded social programs are one way to do so.

But China’s leaders are not completely prioritizing technological development over all other concerns. Huang pointed out that Chinese productivity growth—a key driver of economic growth and overall wealth—has stalled in recent years. Encouraging the development of new industries and technological firms, such as the AI company DeepSeek, should eventually diffuse benefits throughout the economy. And the state has made some efforts to increase household incomes. Starting this year, families will receive a child benefit of around $500 per child under 3, as the Party seeks to reverse the stark demographic challenges created by the one-child policy.

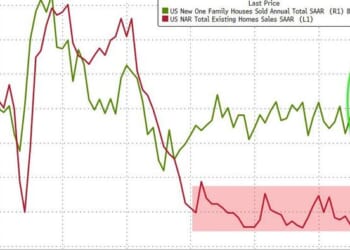

Even so, the CCP will focus its coming Five-Year plan primarily on manufacturing and self-sufficiency, and the average Chinese citizen will likely continue facing similar challenges over the next half-decade. Fángnú, roughly translated as “mortgage slave,” describes a person who spends more than half his or her income on a home loan. This represents a growing percentage of China’s population, and the country’s housing market, which cratered in the early 2020s and continues to slump, will only compound the problem. The weak social safety net also means Chinese citizens tend to save more than in other developed countries. Xi’s personal views, including a dislike of “welfarism,” might also limit the prospects for reform in these areas.

And even though the CCP is willing to prioritize technological advances over bread-and-butter concerns, that doesn’t mean China is destined to become a high-tech superpower. Vibrant private-sector pockets, producing successful companies like DeepSeek and BYD, sit alongside a massive, underperforming swath of state-owned enterprises that account for around a third of the country’s GDP. “There’s no guarantee that their investment in those new technologies will really deliver higher TFP (productivity) growth,” Huang said.

But Xi, fully in command of the Party and the country, plans to move forward in the face of a “complicated international landscape.” Translated from dry Party-speak, that means China is preparing for mounting challenges. Like any good engineer, Xi is tinkering with both the Party and the economy to confront that challenge.