Last week, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman made an announcement. “In December, as we roll out age-gating more fully and as part of our ‘treat adult users like adults’ principle, we will allow even more, like erotica for verified adults,” he wrote on X.

This decision seems to be part of Altman’s larger plan to double down on a chatbot that sounds like an endlessly encouraging companion, rather than a clipped, professional assistant. His choice to allow sexting will have obvious negative consequences for his users—and, just like pornography, it will have serious negative effects on those who never even engage the chatbot directly.

Altman’s announcement framed the issue as though only the users, not he, are moral actors here. “If you want your ChatGPT to respond in a very human-like way… or act like a friend, ChatGPT should do it (but only if you want it, not because we are usage-maxxing),” he said. He argues chatbots should be responsive to users’ desires, including those for sexual role play, but he disclaims his own role in providing a sexbot.

It is odd to treat adult spaces as though the marker of maturity is simply abundant pornography. In response to Altman’s post, one user asked: “Why do age-gates always have to lead to erotica? Like, I just want to be able to be treated like an adult and not a toddler, that doesn’t mean I want perv-mode activated.” Altman ducked the question, replying simply, “You won’t get it unless you ask for it.”

But the cultural impact of increasingly violent pornography makes it obvious he is wrong. Women who have never watched pornography will still meet men in their dating pool who are disgusted by pubic hair, since those men’s appetites have been formed to desire pre-pubescent-appearing women. Women will meet men who assume women commonly enjoy anal sex. And increasingly, women meet men who assume choking is a natural part of sex.

Debby Herbenick, the director of the Center for Sexual Health Promotion at Indiana University, has conducted successive surveys of rough sex practices. In every wave, she finds that choking is becoming more common. In her 2022 survey, 15 percent of women who had ever been choked had been left with visible bruises at least once. About 40 percent had had trouble breathing and 3 percent had lost consciousness.

These acts are dangerous. Even when they are not malicious, they carry a serious risk of death and brain damage. Choking is correlating with risk for further intimate partner violence. At one time, it would have been a stronger sign that your partner desired to harm you. But as choking has become more prevalent in pornography and has crossed over to soft-core shows like Euphoria, men can engage in violence casually, with no ill will.

When Peggy Orenstein, a popular ethnographer of adolescence and sex, conducted Q&As with students, she was surprised by how often choking came up. In 2020, she was asked by a 16-year-old girl, “How come boys all want to choke you?” and then by a 15-year-old boy, independently, “Why do girls all want to be choked?” These young teens hadn’t converged on choking through real encounters with the opposite sex. Their sexuality was instead being shaped by a third party: pornographers. Both boys and girls were being directed away from each other, as they tried to imagine what it would look like to be together.

When, in 2015, This American Life sat in with a group of frat boys taking a sexual ethics class, many of the college boys said they learned how to have sex from watching pornography. They liked watching it, of course, but they also hoped it would teach them to be good at sex—to be good at sex before they actually had any sex with a particular woman.

The story that most stuck with me was that of Nagib, a freshman, whose cousin told him that he needed to kiss girls on the neck. So he did, and was confused and a little betrayed when a girlfriend told him she didn’t like it and wanted him to stop. As he explained it, “When you’re younger, you think, oh, I have to do this step. I have to follow these steps. So I have to kiss her in this certain place. Then I have to make out with her.”

Nagib had been treating hookups like working through an algorithm: If you do the right steps in the right order, you get sex. He wasn’t a bad guy; he hoped it was mutually desired and mutually enjoyable. But, in his own telling, it took him a while to realize that, “It’s not like that at all … Girls vary. Not every girl will like something that you do. Every girl is different.”

A preteen today will be expected to see pornography earlier than Nagib and his frat brothers ever did, and what he sees will be more likely to be violent. Now, with Altman, Elon Musk, and Mark Zuckerberg working to offer “adult” bot experiences (Meta initially approved their bots to sext with 8-year-olds), more and more preteens will be turning to AI to learn how to talk to a member of the opposite sex. We should expect perverse results. Some will stick with their endlessly pliant bot rather than take the chance of a relationship with a real person, one with goals of her own. Some may be confused or upset when a real person doesn’t defer to them the way the bot does. Some are already appealing to bots to upbraid their actual partners. Neither boys nor girls will be well-formed by one-sided relationships.

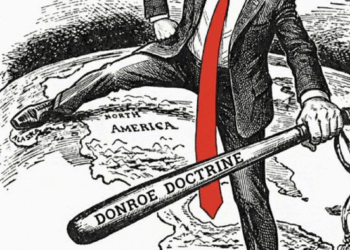

Altman’s initial announcement drew enough blowback that he attempted a clarification. OpenAI’s job was to offer “freedom for people to use AI in the ways that they want,” Altman said, and it was up to users to want good things—or not. If he offered a product that caused users to turn away from real-life friends or grow to expect the same panting sycophancy from a boyfriend as from their bot, those effects were downstream only of the user. As for OpenAI: “We are not the elected moral police of the world.”

There, Altman is correct. When companies have no internal moral force to prevent them from pumping sludge into our waterways or our social currents, we rely on our elected officials to stop them. We don’t have to allow AI erotica to reshape our human relationships. We can attempt boycotts, but vice companies depend on a core of addicted users, not a broad base of customers. We’re better off overhauling our existing obscenity laws so that we protect human speech, not procedurally generated smut. Altman keeps gambling with our future (in more ways than one) while disclaiming any duties to make moral choices. We can’t opt out—except by clipping his wings.