You’re reading Dispatch Faith, our weekly newsletter exploring the biggest stories in religion and faith. Looking for more ways to support our work? Become a Dispatch member today.

Welcome back to Dispatch Faith.

If I’m being honest, there are weeks I worry whether some of the themes we return to frequently in this newsletter are too narrow, or perhaps if we come back to them too often. But especially since the assassination of Charlie Kirk—and at the end of a week in which a vile racist like Nick Fuentes was platformed and pardoned—I think we can’t examine the ways in which our disordered politics are deforming our hearts (or perhaps vice versa) enough.

Author and former political insider Michael Wear is one of the most helpful voices in those conversations. As a matter of full disclosure, I should note that I’ve just concluded a fellowship with Wear’s organization, the Center for Christianity and Public Life, in which my cohort and I spent nine months praying about, contemplating, and writing about the resources Christianity offers to our society’s civic life. Regardless of that Wear, I believe, has a knack for asking the right questions to help us understand what’s going on beneath the surface of partisan or tribal wrestling and what it says about what we believe ourselves, our fellow citizens, and God. He does that again in this week’s essay.

And one housekeeping note: Artificial intelligence reporter Jonathan Gibson makes his Dispatch debut today with a piece on artificial intelligence use from the pulpit, excerpted below.

Michael Wear: Political Hatred Seeps Deeper Than We Think

Since the tragic murder of Charlie Kirk, it has seemed urgent to many civic leaders to insist that words are not violence. This insistence is directed toward making clear that no act of political speech makes the speaker deserving of violence. Certainly, when it comes to questions of guilt or complicity, the distinction between speech and violence is reasonable and, unfortunately, necessary. It is true: political speech, even hateful speech, is not the same as political violence.

However, we stop far too short when we condemn political violence while excusing and contributing to a culture of political hatred.

The reason some people were prepared, quite literally, to justify or even celebrate the assassination of Charlie Kirk the man is that they had grown so accustomed to hating the idea of him. When his image would appear as they scrolled through social media, they might mutter under their breath, “F— that guy.”

One of the lies we tell ourselves is that we can cultivate hatred of someone like Charlie Kirk (or slain Minnesota state Rep. Melissa Hortman or former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi) as “political figures,” and that this hatred will remain quarantined to the abstractions of politics. We have bought into the fiction that hatred mediated and directed by what we consider to be our “good” or “correct” political views somehow makes our hatred righteous. We sanctify our hatreds and even tell ourselves that our loves require hate. We say, “I don’t hate Charlie Kirk, I love my immigrant neighbors,” or “I don’t hate Democrats, I love the truth.” These evasions, this slipperiness, are how we assimilate ourselves to the idea of wishing others ill. It is then only out of the overflow of our hearts that we celebrate when they are harmed.

In the wake of something so horrifying and final as an assassination, it becomes more difficult to abstract the person from the idea we say we hate. But as time goes on, and as our political opponents keep doing things we find to be worthy of scorn, the rationalizations will kick back in. We are told by esteemed political strategists that voters only respond to being given an enemy, and that hatred is the most effective fuel for our politics. We are told that any honest assessment of reality requires hatred.

Stories We Think You’ll Like

The New Medievals

The bones of our conspiracies haven’t changed, though their details are different.

In 1949, Howard Thurman published a radically defiant book, Jesus and the Disinherited. In the work, Thurman—a spiritual mentor of Martin Luther King Jr.—describes “the significance of the religion of Jesus to people who stand with their backs against the wall,” and he singles out hate as “one of the hounds of hell that dog the footsteps of the disinherited.” In a political moment when hate is increasingly lifted up as a tool to be used in our politics, a tactic that can be wielded and controlled to advance specific purposes, it is worth considering Thurman’s diagnosis of how hatred develops once again.

Thurman believed hate needed to be rooted out of the heart of man and of society, but he also believed that mere sentimentality was not sufficient to do so. According to Thurman, hatred had a cause and rationality that deserved to be taken seriously. He describes a kind of four-stage process in the development of hate.

It often begins, Thurman wrote, “in a situation in which there is contact without fellowship.” Thurman saw how this sort of removed interaction—think social media, the very epitome of “contact without fellowship”—creates conditions in which hatred can develop and fester. “Much of modern life is so impersonal that there is always opportunity for the seeds of hatred to grow unmolested,” he explained.

Thurman believed that in this state of contact without fellowship, when we are constantly confronted with one another but never really in a position to be with one another, a strikingly unsympathetic understanding of the other develops. We are close enough to people to observe them, but through that shallow contact we come to develop an understanding of them that is “hard, cold, minute and deadly.” This is the second step. This cold understanding—this ugly portrait that we form in our minds of our fellow citizen, our fellow man or woman—then tends to express itself “in the active functioning of ill will,” And fourth, when that ill will becomes such that it animates a human being, it becomes “hatred walking on earth.” We become, in other words, hateful people who do not have to even think before we revel in the suffering or downfall of others.

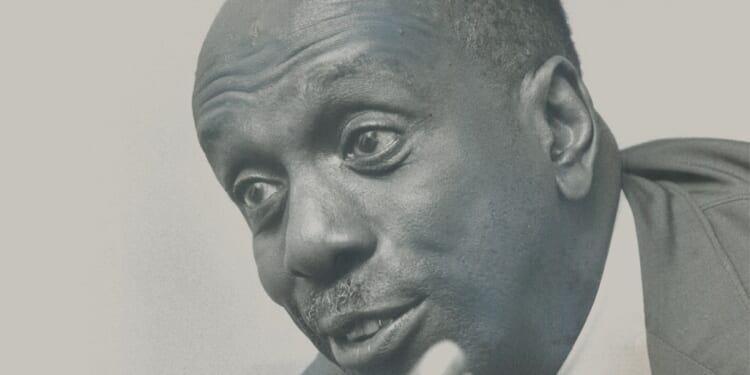

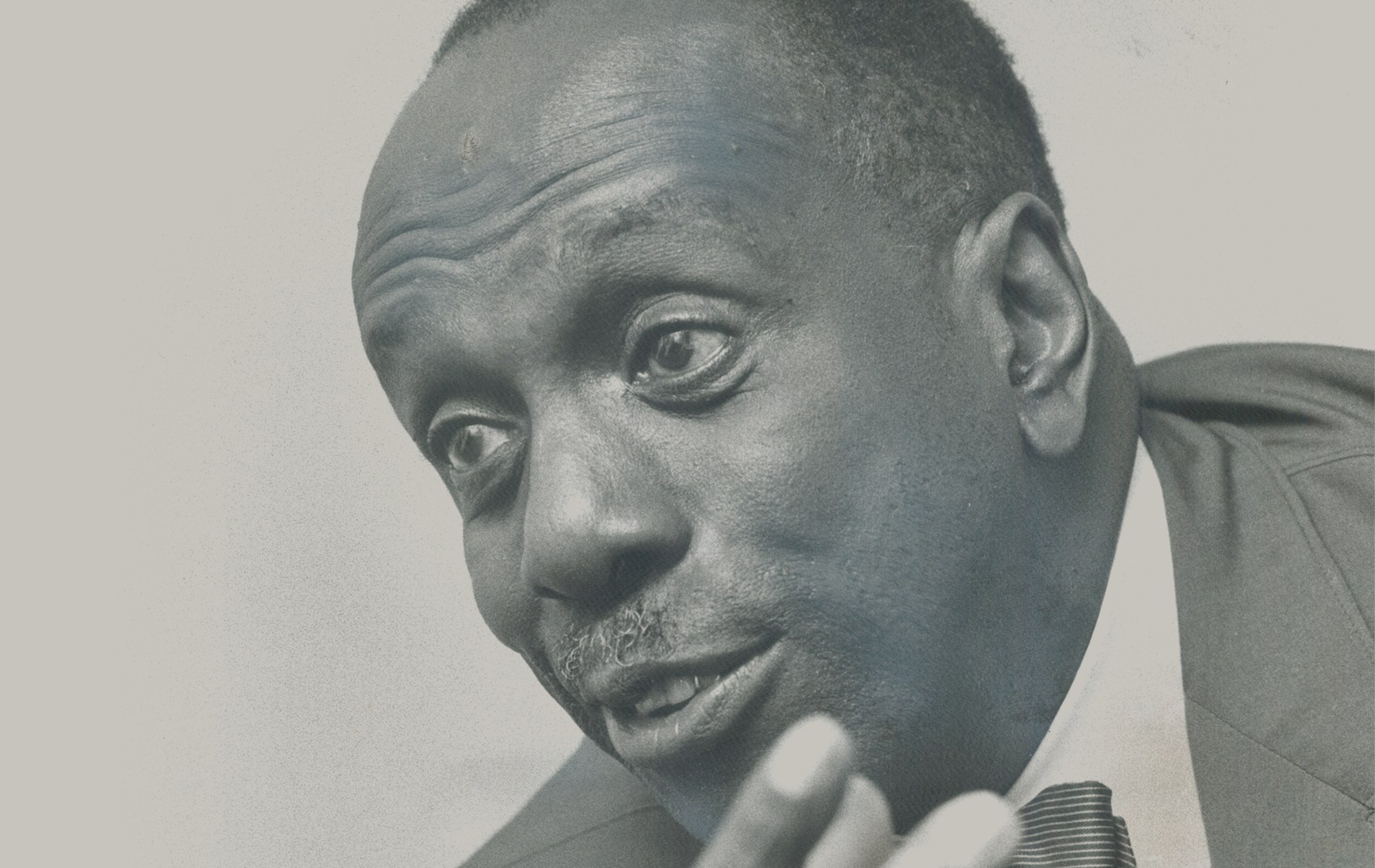

I lead the Center for Christianity and Public Life, a nonprofit with the mission to contend for the credibility of Christian resources in public life, for the public good. We believe Christianity has essential gifts to offer, and that those gifts go beyond the private and personal, but actually flow out to the public and even the political. At our annual summit last month, we honored the Rev. Otis Moss Jr. with our Civic Renewal Award (he was one of two recipients this year, along with Father Greg Boyle). The award honors Christians who have made extraordinary contributions to our civic life, and Moss certainly fits the bill. A close associate of Martin Luther King Jr., his friend who officiated his wedding, and longtime pastor of the Olivet Institutional Baptist Church in Ohio, Moss was a leader in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and was there with King in Selma, Alabama.

In a letter accepting the award, he wrote:

Let it be forever remembered that all racism and hate lead to genocide, (Professor George Kelsey taught us this decades ago), past, present and future. In a society of hate no one is safe. The haters and the hated are in constant danger.

However, Love, Justice, Liberation, Transformation and Reconciliation must be our abiding commitment. This commitment must be kept alive and active from generation to generation.

Our prayer must forever remain: Dear God, make me too brave to hate and too courageous to be unkind.

This is hard-earned wisdom from someone who has seen hatred up close, who has battled it. We should heed his warning. We should make his prayer our own. The point is not that those who had every reason to hate were able to resist hatred as an expression of courageous self-rejection. The point is that we should question the grounds, the rationality, of hatred in the first place. The denial of hatred is not an act of asceticism that we should only pursue as a prerequisite to piety. If we could see from the outside what hatred does to our hearts, not to mention those around us, we would not spend so much time seeking to define exactly when hatred might be most permissible. We would know that we need to turn from it before it devours us whole.

I am concerned about where we go from here. The pseudo-catharsis of a politics of hatred, particularly in this moment, is a great temptation. But it is a temptation that must be resisted. Voters should reject appeals to their basest instincts, their instinct to wish the worst for those they view as their political enemies, and instead embrace a politics that puts forward the impulse to love, to seek the good of all who share in this project of self-governance with us, regardless of their willingness to do the same.

The hatred we allow ourselves to nurture and express day by day is training our hearts to conduct and condone violence when the opportunity arrives. It is not just the act of violence but the spirit of violence that must be opposed. It is not just the action to harm another that must be opposed, but the desire that harm would fall to another. If we do not have the courage to pursue a politics of love, our political heart will become consumed by hate.

We are lying to ourselves if we think we will make real progress against political violence without confronting the hatred that now pervades our political life.

Jonathan Gibson: Does AI Have a Place in the Pulpit?

The newest member of The Dispatch team is Jonathan Gibson, a reporter who will be covering artificial intelligence. His first piece for us examines how Christian, Jewish, and Muslim clergy are using AI in writing sermons.

“I personally feel like there is an opportunity here to go out of your way to not use AI for sermon-writing,” David Zvi Kalman, a research fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute’s Kogod Research Center in New York, told The Dispatch. “And it’s not because AI wouldn’t do a good job.”

Kalman referenced a recent Pew Research study, which found that 73 percent of people do not want AI to play a role in advising them about their faith. “There’s an opportunity here actually to kind of harness public opinion on the matter and say like, okay, you know, we’re creating these spaces in which you can be assured this is a kind of human-to-human interaction … you’re not reading words written by a robot,” Kalman said.

Religious institutions’ resistance to new technologies often seems awkward at first, but, Kalman argues, those acts of restraint can grow in meaning over time. He points to the Jewish Torah as an example. By continuing to use scrolls instead of the more efficient codex, Judaism has preserved a physical and spiritual distance between sacred text and everyday reading. That very distance, Kalman says, has only enhanced the Torah’s significance. Through preserving the unique method of producing and reading the Torah across generations, the sanctity and sacredness of the text is elevated in its uniqueness and distinctiveness from other texts. The same, he suggests, could one day be true of sermon-writing, in its retention of a skill that may otherwise degrade through reliance on AI. “Going out of your way to preserve human writing in this specific context is one of those things that can gain meaning over time,” said Kalman.

Across all faiths, scholars and leaders are weighing in on these same questions.

Another Sunday Read

- Perhaps something a bit different: In the London Review of Books, Em Hogan reviewed a book that includes some perhaps counterintuitive religious roots of tattooing. “Matt Lodder’s Tattoos: The Untold History of a Modern Art focuses on the history of tattooing in the West,” Hogan wrote. “His story begins in the 18th century, by which time tattooing had become an established commercial activity in the Middle East. Images of the crucified Christ or the skull of Adam were popular souvenirs among European pilgrims returning from the Holy Land. In 1658, the French pilgrim Jean de Thévenot described Christian tattooists in Jerusalem using wooden blocks to stamp religious symbols—often crosses—onto the skin of visitors before pricking in the ink: ‘They have several wooden moulds, of which you may choose that which pleases you best, then they fill it with coal dust, and apply it to your arm, so that they leave upon the same the mark of what is cut in the mould; after that, with the left hand they take hold of your arm and stretch the skin of it, and in the right hand they have a little cane with two needles fastened in it, which from time to time they dip into ink, mingled with ox’s gall, and prick your arm all along the lines that are marked by the wooden mould.’” (If you’re interested, I wrote about my own tattoo last Thanksgiving.)

Religion in an Image