On Saturday, May 27, 2006, then-Vice President Dick Cheney traveled to Wyoming to give one of the most important speeches of the many thousands he would deliver over the course of his 84-year life.

It came at a busy time: graduation season.

Cheney had spoken one week earlier at Louisiana State University’s commencement ceremonies, where a graduate student strode directly in front of the vice president to fetch her diploma while wearing a hunting vest over her gown and a bullseye atop her cap, mocking the vice president for shooting one of his hunting buddies earlier that year. (Cheney later instructed the school’s chancellor to “find out who she is and tell her I thought that was well done.”) A few days later, he spoke at the U.S. Naval Academy, delivering a speech focused on duty and honor.

All the while, Cheney was carefully monitoring events in Iraq, where violence against both American troops and Iraqi civilians was continuing without an end in sight. The regime in Iran was once again refusing to cooperate with international nuclear inspectors, and the country’s leader was issuing increasingly threatening statements against both Israel and the United States. Cheney was involved in delicate negotiations with senior Justice Department officials and House leaders over an FBI raid of Democratic Rep. William Jefferson’s office, and he was trying to mollify congressional Republicans opposed to an immigration reform package the administration was pushing. In a development of perhaps the greatest personal import to Cheney, the New York Times had reported that the vice president might be called to testify in the trial of Scooter Libby, his former chief of staff.

In Wyoming, Cheney didn’t talk about any of that. Addressing the 340 graduates of Natrona County High School—his alma mater and that of his wife, Lynne—the vice president delivered a speech that he had written aboard Air Force Two en route to Casper.

Stay focused on the job you have, not the next job you might want. In your careers, people will give you more responsibility when they see that you take your present job seriously. Do the work in front of you. Try to find ways to make yourself indispensable. And I can almost guarantee that recognition, advancement, and other good things will follow.

I think there’s a lot of truth to the old wisdom that you should choose your friends carefully. They have a big influence on the kind of person you become. So when you see good qualities in people—things you admire, habits you’d like to pick up, principles you respect—keep those people close at hand in your life. In many ways, when you choose your friends, you choose your future.

Diligence and character. For those graduates paying careful attention, Cheney had just described the simple wisdom he followed on his path from Casper, Wyoming, to becoming the most powerful vice president in American history.

Over the course of his nearly four decades at the highest levels of the U.S. government—from White House staff assistant in the Nixon administration to White House chief of staff in Gerald Ford’s, from congressional leadership to secretary of defense to being elected vice president—Cheney did the work in front of him. Nobody who has had the kind of career Cheney had can be described as ambitionless, but at each of these stops, in different ways, he prioritized substantive, behind-the-scenes work over self-aggrandizement and attention.

Upon first arriving in Washington for a fellowship, Cheney opted for a policy role in the office of a relatively obscure congressman—Rep. William Steiger of Wisconsin—rather than press work for a famous senator. He chose the unglamorous work of the Cost of Living Council in the Nixon administration over a position on the Committee to Re-elect the President (CREEP). He took a short-term job in a small consulting firm rather than as a top aide to the U.S. ambassador to NATO. When he was named chief of staff to President Gerald Ford, he declined the Cabinet-level status that came with the title.

In Congress, he opted for far-from-the-spotlight committee assignments, such as the House Intelligence and Budget Committees, over more prominent posts available to a member of Republican leadership. He gave very few floor speeches, even as chairman of the House Republican Policy Committee, and media appearances were very rare occurrences. During the Gulf War, when Cheney was serving as secretary of defense, Cheney asked Colin Powell, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to handle the regular on-camera briefings about the status of the conflict.

George W. Bush didn’t know these details when he first approached Cheney about serving as his running mate, but others who were advising him did. And in the end, Bush chose Cheney in no small part because of his well-earned reputation as a workhorse in a showhorse town. What Cheney couldn’t provide in electoral benefits—Wyoming was the least populous state in the country, with fewer than 500,000 residents—he would bring in governing experience if they prevailed. Cheney agreed to serve in what he had described four years earlier as “a cruddy job,” in large part because he understood from Bush that his responsibilities would be far from the ribbon-cutting-and-funeral role that had come to characterize the modern vice presidency.

Cheney’s expansive role quickly became a topic of discussion in the nation’s capital and beyond, with Democrats and some journalists suggesting that the vice presidency was the true locus of power in the White House. At one point, Saturday Night Live parodied the arrangement, with “Bush” seeking permission for all manner of things from “Cheney.” Senior Bush administration officials were sensitive to the subject, even if they understood better than outsiders that such perceptions were untrue—or at least incomplete.

The reality wasn’t terribly complicated: Dick Cheney was a powerful vice president because George W. Bush wanted him to be a powerful vice president. Even before the attacks of September 11, 2001, that would shape so much of the Bush presidency, Cheney had a leading voice in every policy discussion he chose to join, usually reserving his advice for one-on-one conversations with the president. Cheney’s role grew further after the World Trade Center fell, not only because of his experience with the Pentagon and intelligence community, but also because he had for years been deeply involved in kinds of continuity-of-government exercises that imagined exactly the kind of threat environment the 9/11 attacks created. Condoleezza Rice, who served with Cheney in the Bush administration as national security adviser and then secretary of state, told me that his greatest influence as vice president was in his “intellectual contribution to the conceptualization of the war on terror.”

If Cheney’s experience was a primary reason for his influence, so too was his lack of ambition. Cheney was, as he might have put it, focused on the job he had, not the next job he might want.

And that, too, made him unique.

“You’ve never read a story where the vice president’s office is concerned about the recent presidential decision, what it may do for the X, Y, Z. And that even keeps Richard Cheney—Dick Cheney—closer,” Bush said in a 2007 interview. “It makes it much easier. I am blessed to have a guy who is smart, capable, and tells me what’s on his mind, and doesn’t have a political bone in his body.”

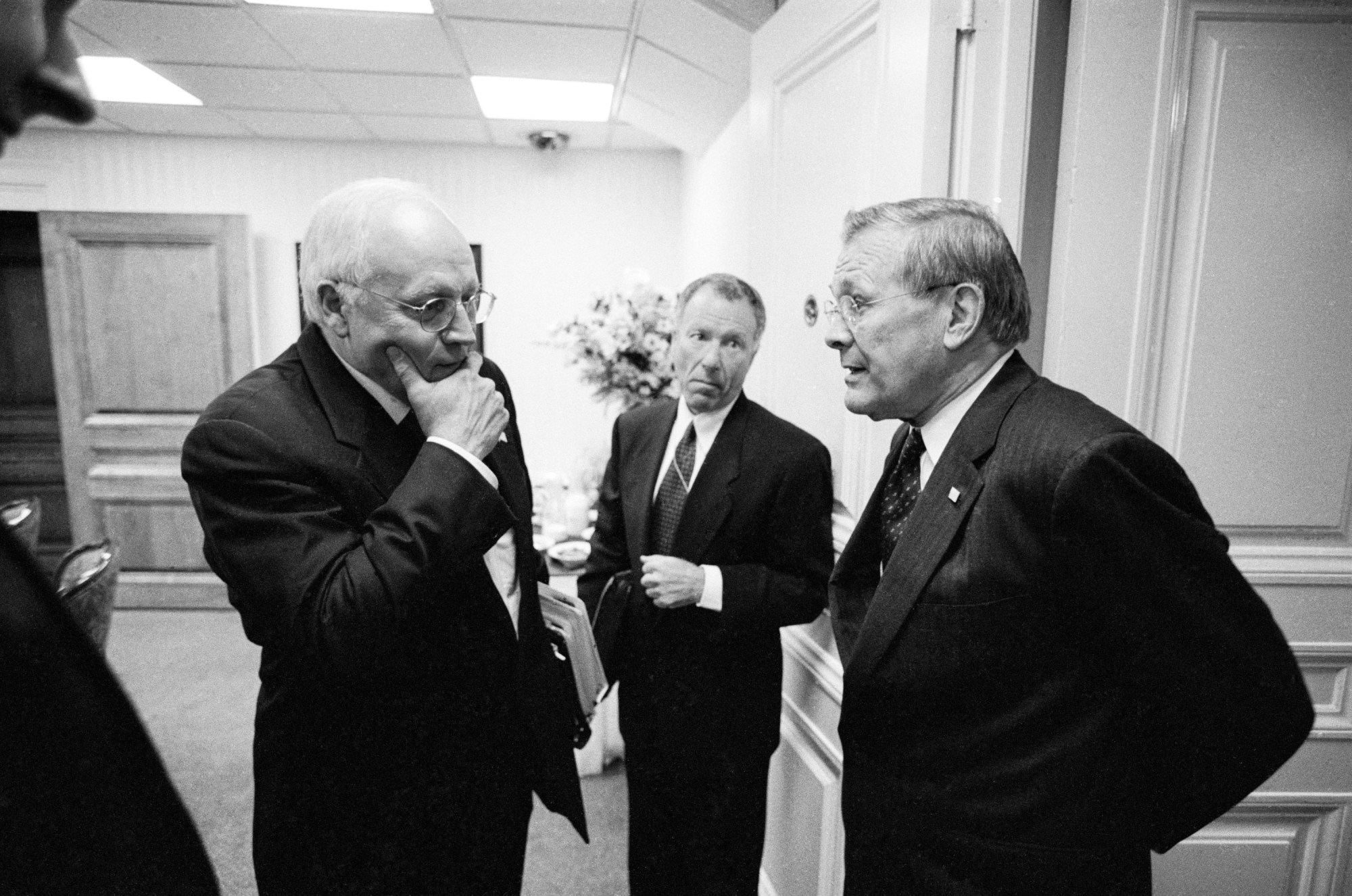

Cheney also lived by his advice to those Natrona County High graduates on character. Nowhere was that more evident than in his relationship with Donald Rumsfeld. Cheney got to know then-Rep. Rumsfeld early in his time in Washington and went on to work closely with him in the Nixon administration. When Rumsfeld was named chief of staff to President Gerald Ford after Nixon resigned, his first call was to Cheney, offering him the job as his deputy, pending an acceptable FBI report after a routine background check.

But Cheney’s background investigation was far from routine. He had dropped out of Yale University after the school revoked his scholarship due to poor academic performance, returning to Wyoming and working as a telephone lineman. Within a matter of months, he was arrested twice for driving while intoxicated.

Rumsfeld hadn’t known about these incidents, and he wasn’t happy to learn about them. When calling Cheney in to grill him about the arrests, Rumsfeld was particularly interested in whether his would-be deputy had voluntarily disclosed his legal troubles as required on the FBI forms. When Cheney assured him that he had, Rumsfeld agreed to make the case to Ford directly that Cheney’s record shouldn’t be disqualifying. “I spent a good deal of time with the president, who of course did not know Cheney at all, and convinced him that this was a good guy,” Rumsfeld recalled. In his view, the arrests themselves were less important than the fact that Cheney had owned up to them.

It was a pivotal moment in Cheney’s career. If Rumsfeld hadn’t vouched for him, Cheney would never have become the youngest White House chief of staff in history. “It impressed the hell out of me that he was willing to stand by me,” Cheney later told me. It was a loyalty that Cheney would repay three decades later when Rumsfeld served as secretary of defense during America’s wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Although he and Rumsfeld disagreed about the number of troops on the ground required, Cheney went out of his way in public—and in internal administration deliberations—to avoid the appearance of any daylight between him and his longtime mentor. And when Bush, with the backing of most of his national security team, eventually decided to replace Rumsfeld in 2006, Cheney gave a speech at his departure ceremony in which he pointedly said, in Bush’s presence, that Rumsfeld was the best boss he’d ever had.

“My first association with Don Rumsfeld was one of life’s great turning points, both professionally and personally,” Cheney said at the time. “On the professional side: I would not be where I am today, but for the confidence that Don first placed in me those many years ago. And on the personal side: It’s enough to say that I have no better friend, and ask for none.”

Then, with Bush sitting just a few feet away, Cheney added: “I’ve never worked harder for a boss, and I’ve never learned more from one, either.”

Dick Cheney’s long political career ended less than 20 years ago, but the profound changes to our country since he left office make it seem like a different era. The attributes that drove his success—diligence, discretion, policy mastery, character—feel ever more anachronistic in a political moment that prioritizes attention and outrage.

“In this world, there is information and opinion—and then there is knowledge and wisdom,” Cheney told the crowd at Natrona County High School that day. “And a lot turns on knowing the difference.”