One thing that typically divides what might be called left-leaning liberals from the classical liberals associated with American conservatism (e.g., Reaganites) is that left-leaning liberals are more prone to dismiss the significant impact that cultural and marital/sexual norms have had on the success of liberal democracy. That is not to say that all left-leaning liberals do this. But for some of them it is almost a first principle that as long as you are not harming others with your lifestyle, especially as regards family and sexuality, then no regulations or social norms should legitimately restrain you. Conservative liberals, on the other hand, tend to favor the social regulation of such behavior: norms and taboos, or even subtle policies. Recent news about the political rise of resentful young incels like Nick Fuentes should cause left-leaning liberals to take this conservative-liberal concern more seriously.

One of the best books I have read in recent years is The WEIRDest People in the World by Joseph Henrich, an anthropologist at Harvard. In the book, Henrich makes a case for what he sees as the entirely unique psychology of members of Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) societies, based on his extensive studies of cultures around the world. WEIRD people are more analytical, individualistic, and cooperative with strangers than other people; they are also prone to a universalistic ethics that transcends their tribe. We WEIRDos are thus particularly prone to, and suited for, liberal-democratic government. All this should matter to anyone, left or right, who sees constitutional democracy as a blessing. If we want to preserve that order, we should preserve the factors that led to it.

According to Henrich, one significant contribution to the development of WEIRD psychology was the effort by the Catholic Church to discourage and even ban cousin marriage in Christian Europe. Henrich argues that this new prohibition broke kinship bonds, forcing people to find mates outside their kin and cooperate with strangers, contributing to the development of public institutions based in trust. Another contributor to WEIRD psychology was the development of mass literacy after the invention of the printing press and the educational reforms of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, increasing literacy from the perennially low rates of the ancient and medieval worlds (10 percent to 20 percent at maximum) to the near-universal literacy we take for granted in the modern world.

For my purposes here, however, the most relevant contribution to the creation of WEIRDos was the banning of polygamy, a practice that was permitted in 85 percent of human cultures across time. That’s not to say monogamous marriage was not the norm in those cultures—it was—but elite men were permitted to take multiple wives. The effect on those societies was significant, with roughly 40 percent of the male population forced, by what Henrich calls polygamy’s “number problem,” to be involuntarily celibate. Today, we would call those men “incels.”

The research of people like Henrich, in some ways vindicates the above-mentioned concerns of the conservative liberals. A return to a 40-percent rate of involuntary celibacy would be a disaster for our society. Why? Because the tendency Henrich finds in all these cultures is that the involuntarily celibate are driven by the desperation and resentment, caused by lacking a mate, to risky, dangerous, and criminal behavior. In one 2006 article, Henrich and his coauthors cite modern evidence of a causal relationship: One study tracked boys, who had attended a Massachusetts reform school, from age 17 to 70, and found that marriage was correlated with reduced crime rates.

“Most subjects were married multiple times, which allowed the researchers to compare their likelihood of committing a crime during married versus unmarried periods of their lives, using each individual as his own control,” Henrich and his coauthors wrote. “Across all crimes, marriage reduces a man’s likelihood of committing a crime by 35 per cent. For property and violent crimes, being married cuts the probability of committing a crime by half. When men are divorced or widowed, their crime rates go up.” One potential cause that Henrich mentions is the higher testosterone levels of mateless males, which tends to make them more aggressive.

If we think that resentment is a problem in politics now—and it is—imagine politics when 40 percent of adult males are incels. Assuming half of the around 260 million adults in the U.S. are male, 40 percent of those 130 million men would constitute around 52 million people. Donald Trump won the 2024 presidential election with 77 million votes. Motivated by resentment, similar numbers of incels could capture either party’s primary electorates, which even in a competitive primary have no more than 30 million voters each. In an “incel republic,” we might not have to worry about J.D. Vance as the next GOP nominee; we might instead have to worry about someone more like Nick Fuentes, a self-described incel who leads a cult of unusually resentful young men. And even if incels did not join the electorate in sufficient numbers, they would create a population of potential zealots whose resentment demagogues could easily exploit.

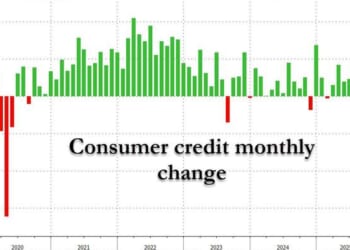

We’ve thus avoided a scenario like this, in part thanks to the banning of polygamy. But even without polygamy, a similar numbers problem can occur if the marriage rate becomes low for other reasons. In an article from 2018, the demographer Lyman Stone wrote that the most promiscuous males take on a disproportionate amount (60 percent) of sexual partnerings—which is more conservative than the related 80/20 narrative of incel writers, but still significant. We know from other research that those men are generally those with less interest in commitment and who are more savvy and aggressive in strategizing short-term hookups. (It is also true that more promiscuous women take part in a disproportionate amount of partnerings). Since those proportions are fairly stable over time, if there is evidence of a rise in young male sexlessness, which Stone acknowledges, it is mostly explained by a declining marriage rate. Incels might want to complain about women excluding them, but it is unlikely that the balance of unmarried sex will change significantly. The problem is not, therefore, that young women owe these young men more equitable non-marital sex. It is that too few of both are married.

It is for reasons like this that philosophy professor Dan Demetriou defends legal prohibition of polygamy and other social efforts to promote monogamous marriage. This is legitimate, he argues, out of civilizational concerns just as it is legitimate to support environmental laws and stewardship. Of course, you cannot force people to get married. But it seems reasonable to encourage monogamous marriage through education, social mores, and subtle family policies. This idea is not new. It is basically the idea of “human ecology” that one would frequently hear from older, typically more religious fusionists like Michael Novak.

Among social conservatives today, there is no shortage of those who would rather undermine liberal democracy to fix this problem, handing power to a strongman who can force solutions on an unwilling populace. Consider the preference for Viktor Orbán, or even the Chinese Communist Party, among some postliberals. One thing that attracts them to Orbán in particular is his aggressive family policy (e.g., exempting women with four or more children from paying income tax, family housing support programs). We fusionists may agree with them about the problems, but we cannot support their solution if that means giving a strongman autocratic power. We can, however, meet them halfway, for instance, by supporting policies that increase the child tax credit, or by zoning reforms to increase the supply of housing and reduce the cost of a home.

Those are also policies that can be supported by the left. But more important than sensible family policies, we must do something to create a culture that promotes male responsibility and commitment, preparing young men to be more marriageable to young women. That will take abandoning old liberal taboos about promoting marriage and family in public discourse. Lifestyle pluralism has its limits. If you care about liberal democracy, whether you are on the left or the right, say it out loud: Marriage is good, and we should prepare young men for it.