It was the last winter of America’s holiday from history—less than a year before September 11, 2001—and as cold as you could expect from a winter day in Chandler, Arizona, at around 60 degrees. My mother and her parents were there to greet me on my entry into this world, alongside the doctor who cut my umbilical cord and checked my vitals. My grandfather drove me home that day, a slightly worn “McCain 2000” campaign sticker on his bumper.

I am what previous generations called a “bastard child,” though I don’t consider myself much of a bastard (others have mixed opinions). That I was born without a father was not something I understood as significant for many years. Those born fatherless, like those born blind, never fully understand what they’ve missed. My childhood is filled with fond memories. Staring out the window of my grandparents’ Sedona home with its view of Snoopy Rock, eating scoop after scoop of homemade vanilla ice cream, playing tag with friends in the cool evening, zig-zagging through cacti-dotted nature and suburban homes adorned in desert tones.

Standing in our home was a statue of Saint Joseph. I barely noticed him as a child, but after I’d grown a bit older, my mom told me the story of how I’d received my name. The day she was told that I had spina bifida—only a few months in the womb—she left her doctor’s office in a frenzy, pacing around a nearby flea market. Terror was all she could feel. She happened upon a kiosk selling saint medals, and on a whim, recited a prayer: “God, if you save my child, I will name him after whichever saint medal I buy.” She left her glasses at home that day and could not discern one medal from another. She thought she bought Saint Jude. It was Saint Joseph.

The next day her doctor called, telling her that the diagnosis had been a mistake. Saint Joseph must have said a mighty prayer for me. My mother kept her promise to God.

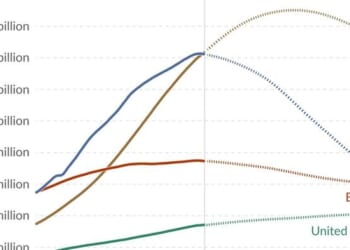

Around 60 years ago, Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan published a landmark report about fatherlessness among economically disadvantaged black Americans. That nearly 25 percent of urban non-white fathers were either divorced or absent from their children’s lives was, back then, evidence of a national crisis (for the purposes of this essay, “fatherlessness” encompasses those whose fathers are still alive but not involved in their children’s rearing—it is them that I am most concerned with, not those whose fathers have passed away). Today, 25 percent of all American children are raised without fathers. A startling 54 percent of Hispanic children and 72 percent of black children are born out of wedlock. While some voices have raised concerns about these statistics, most of us have shrugged and moved on—better not to ask difficult questions that might upset progressive pieties.

Stable families with present fathers are remarkably strong predictors of a child’s future success. “Kids who are raised [by] their own married parents are twice as likely to graduate from college … the boys are half as likely to end up in prison before age 30, and we also see girls are half as likely to be depressed as teenagers,” says Brad Wilcox, a leading family scholar. The presence of a father in a child’s life has also been shown to foster independence and courage, emotional resilience, and cognitive development (an involved father is the strongest predictor of a child’s likelihood of graduating college). Moreover, per one recent survey, young men in particular “look most to their father (39%) for guidance followed by friends or peers (22%) or their mother (21%).” Fathers still disproportionately serve as financial providers: Despite some convergence in the last several decades, men are three times as likely to be primary breadwinners than women.

But fatherhood is more than instrumental. Indeed, “[i]f a man is primarily a provider narrowly construed—a recurring direct deposit in his family’s bank account—then he can be abstracted away,” writes Dispatch contributor Leah Libresco Sargeant in her recent book, The Dignity of Dependence: A Feminist Manifesto.

Instead, fatherhood is an institution that embodies the extension of a man’s physical strength for the protection of the vulnerable. “Historically, just as a woman might expect to enclose and shelter the vulnerable with her own body, a man could expect to extend his physical body over others as protection,” writes Sargeant. That said, fewer men today are in positions where they must utilize their strength and potentially risk their lives for the sake of others. As Kevin Williamson wryly observed, “the times being what they are, a man is not called to fight a bear very often.” But a father’s role remains unchanged. Fathers are still relied upon to pick up heavy things, care for their wives throughout pregnancy, and drive their kids to Little League practice. And though there are still certain times where kids want their mother, not their father, Williamson writes that fathers have the privilege of being what he describes as “the marginal parent”—of being the parent who goes the extra mile once mom has expended herself to get their kids to the finish line.

Fatherhood is a challenge—a call to action—that rouses men from the complacency of absenteeism to the grand risk of rearing a human being and putting one’s life on the line for them. This grand duty often manifests as a great many small duties: Waking up early to get the kids to school, getting off work to take your kids to soccer practice, staying up late to do the dishes so that your wife can finally get some well-deserved rest. Fatherhood provides meaning precisely because it involves risk. Fatherhood is the unique institution that channels men’s natural strengths for the protection of and provision for others—by a man’s choice to be an active presence in his child’s life, to submit to the duties of fatherhood, his love is drawn out and directed toward his wife and children.

Various theories have been proposed to explain why fewer and fewer children are being raised with fathers in the home. One explanation follows Sargeant’s above argument: Our decadence and comfort have made men and women less aware of the dangerous realities of life, and we have therefore discarded institutions like fatherhood and marriage because they are no longer as functionally useful. Ross Douthat, a New York Times columnist, argues along these lines in The Decadent Society: How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success. Others point to the equalization of gender roles in the wake of the sexual revolution: Women have (thankfully) gained more rights, and therefore it is easier than ever—legally, financially, socially—for spouses to divorce. And women are overwhelmingly more likely than men to retain custody of their children following a separation.

What all of these converge on is that the recent rise in fatherlessness is not the result of dads suddenly becoming more selfish. Accounts of any type of social breakdown that attribute its cause to people becoming less inherently virtuous strike me as incredibly naive and childish—man fell once and we’ve been fallen ever since. Structural explanations do not absolve absent fathers of their selfish decisions. They do, however, help to explain why men’s connections to their children seem to have grown more tenuous.

David Foster Wallace began Kenyon College’s 2005 commencement address with a short story:

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”

“The point of the fish story,” Wallace later says, “is merely that the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about.” When something becomes so common so as to no longer be exceptional, it’s all the easier to ignore or discount. While I’ve already addressed how we’ve succumbed to this temptation as a society, this parable has deeply personal implications, particularly for the fatherless.

Throughout elementary and middle school, I struggled with crippling existential anxiety. A legion of therapists concluded that my malady was caused by equal parts chemical imbalance and suppressed trauma regarding my father’s absence. I could never quite understand how I was supposed to know whether this was the case. Mention of my father didn’t provoke any negative emotional response. I would see him from time to time as a kid, and we always had a lovely time. Nonetheless, the therapists’ conclusions seemed plausible enough, and the solutions provided included additional one-hour sessions on the couch and a prescription for Zoloft. Not much came of either, aside from some weight gain.

Like the fish in Wallace’s parable, I did not understand the significance of my fatherlessness because I had always been fatherless. Likewise, growing up, I did not recognize the presence of Saint Joseph, the patron of fathers, because he had always stood next to my front door. It was only after the passage of time that I even thought to ask the question, “Who’s that, mom?” It is near-impossible to grieve something—someone—who was never there in the first place. As a child, I knew not what to grieve because I knew not what was lost. But the hole in my heart, once vague and undefined, has come into focus with the passage of time.

Conversations surrounding fatherlessness are often discussed impersonally, as statistics and facts and posited causal relationships. Such conversations must be had, especially among researchers and policymakers, but we must understand that the experience of fatherlessness is something altogether different. And its ubiquity is both a cause and effect of our world’s escalating social atomization.

Today, most Americans understand “freedom” to mean what political theorist Isaiah Berlin defined as “negative freedom”: a state in which one’s desires are free from frustration “by other human beings, directly or indirectly, with or without the intention of doing so.” In our pursuit of this freedom we have severed ourselves from “obligation.” “Shame” is a dirty word, and “guilt” anathema. In stigmatizing stigma we have torn down every institution that demands certain things of certain people; that demands people live up to certain standards, especially in moments of temptation.

In freeing ourselves from social constraints and the shame that naturally accompanies our shirking of natural obligations we were promised paradise. We have instead found ourselves lonely and rudderless. President George W. Bush spoke of the bigotry of low expectations. We have succumbed to the misery of no expectations.

A family’s legacy—embodied in property, capital, cookbooks, passed down stories, genealogies, and heirlooms—is at least partially denied to any child born without a father. (This is also the case for many of those born without active and involved mothers, but in 80 percent of cases, mothers are leading single-family arrangements, not fathers.) We are not only denied the loving affection of a father, but the firm basis of a family legacy that grounds us in something greater than ourselves.

While I grew up my father gifted me an assortment of strange trinkets: an axe and shield from some African tribe, a replica Civil War cavalry sword, a flintlock pistol, and military uniforms of all varieties. These gifts were tributes offered in place of his active presence in my life: I only saw him a couple dozen times from the time I entered the world to the day I turned 18.

Being a father requires more of a man than his participation in his child’s conception. It requires loving commitment and a willingness to sacrifice in order to raise sons and daughters who will one day live and operate in the world as independent adults. My father chose not to play that role in my upbringing. I’ve chosen not to spite him, but to love him, to call him “dad” even if he didn’t play the role he ought to have when I was a boy. Only by taking the risk of loving him will I learn what fatherhood really is: An institution that conjures and shapes our desire to love and serve others. That will mean understanding ever more clearly what I missed out on, but it will also mean understanding ever more clearly what my future children deserve from their father.

My dad likes smoking cigarettes and making friends with strangers. He loves reading the histories of empires, particularly the Romans and the English. He attends an Episcopal church where my dear uncle Jeff serves as a deacon, not because my dad believes in God, but because he enjoys having something to do. His politics are eclectic: He’s a Southwestern libertarian who loves guns, opposes government regulation of everything from marijuana to gay marriage, and despises contemporary authoritarians while harboring a strange affection for the tyrants of antiquity. Serving in the Peace Corps for two years, he traveled throughout French Africa, picking up half a dozen African dialects and French along the way.

Visiting his family’s house in southern Arizona was always a journey backwards in time. Large bookshelves loomed over antique carpet and furniture, chock-full of volumes ranging from Das Kapital to A History of the English-Speaking Peoples. A stuffed lion head sat atop a coffee table, the spoils of a not-so-distant ancestor’s safari. Items from every continent perhaps besides Antarctica were strewn across tabletops, nestled in nooks and crannies. This house was a reminder that I was connected to a great past by blood. But I remained alienated from it by my father’s absence.

One warm Western evening several years ago, my father, my half-sister, and I sat round a fire. We drank beer and smoked cigarettes, conversing about politics, the historicity of the Gospels, and the divergent paths we’d all taken. As we grew more comfortable, I felt compelled to tell my father about how I sought to build a legacy. I wanted something of me, of my family’s history, to live on beyond me. My father’s eyes lit up. It was not my dream alone. It was my father’s, and his father’s, and his father’s father’s. His longing for a legacy that lived on beyond him had seemed quixotic for some time—that was, until that evening we sat round the fire. He thought the Bailey line had ended, its legacy forever erased by his decision to shirk the risk of raising his son.

That evening, I believe, was the first time my father saw me as a man. A man who was not the helpless victim of his father’s mistakes, but a force in his own right—a man with the want and will to preserve what came before him so that he might build something that lives on after him.

Soon after we sat round the fire, my father gave me a short book. Published in 1944, it was written by his great-great grandfather just before his death. It is titled House Warming at ‘Three Acres’, Three Acres being the name of my family’s now-sold-off farm in upstate New York. My great-great-great grandfather dedicated the 22-page document “TO MY GREAT-GRANDCHILDREN,” beginning with the story of how he invited living family to gather at his hearth on the 17th of November, 1944:

Besides your great-grandmother and myself were your grandfather and grandmother, Claude Moore Bailey and his wife, Martha, and their sons, Joe and Bob. These were all of the family that could be there in person. There were many others of the living who came in spirit and later on in the day and into the night came a vast throng of ghosts out of the past, ancestors of yours who came to bless the hearth and assure us of their concern for all descendants and their guidance in everything they do.

He goes on to document all the family history he could piece together, sketching a legacy that I had never before understood with such detail. My great-great-great grandfather refused to end his history in the past. It was addressed to his progeny, after all:

The future always brings unlooked for surprises and even great and unanticipated blessings, as if to fulfill some law of compensation. To tide over fears and despairing moods, you may well look to the motto on the Moore Coat of Arms, ‘Fortis Cadere Cedere Non Potest,’ [the brave may fall, but cannot yield] which may help carry you on to good fortune. It is this spirit which has brought your line on, so far, and will doubtless continue it.

In another universe I would be Claude Bailey V, my name a living testament to a lineage of men that graduated from the Naval Academy, traversed the world from Cairo to Buenos Aires, worked Three Acres from dawn to dusk, and served in the Peace Corps. In this universe—the one that matters—my name is Joe Pitts, first of my name. I remain an heir to my father’s legacy but have been granted the freedom, by bastard birth, to chart my own path. In our time we praise this sort of freedom. Yet I ache for a childhood that could have been different, a connection to my father’s past that has otherwise been severed, a birthright denied.

Modern freedom has much to commend itself, but true freedom cannot be exercised without a solid foundation, a foundation provided by all the things we don’t choose in life: namely, who our parents are. This foundation gives us a framework, however imperfect, to navigate the journey of life—it grants us a blueprint for how we might extend our own natural strengths to love and serve others. Those born without fathers aren’t out of luck, however. I was blessed with loving grandparents who helped my mother raise me, and their example, paired with my mother’s grace under the pressure of single motherhood and a full-time career, are pearls of inestimable personal worth. Role models, religious communities, and civil society institutions that transcend blood bonds can also play a powerful role in building this foundation for young people.

Ultimately, despite all of the barriers facing the fatherless and rudderless, each of us is left with a choice. Do we choose to become victims of our father’s absence? Do we choose to let his hesitance to take the risk of loving his partner and children live on in us? No—we ought to actively choose to love others and build a solid foundation for our future children precisely because we know the struggle concomitant with being raised without such a foundation.

I’m comforted by the vision of my future children one day perhaps looking back and feeling gratitude for how I loved them, for the legacy that was passed on to them. Perhaps one day we, too, will sit round a fire and invite the ghosts of our past to join us. Though they may share my name, it will ultimately be their choice, as it was mine, whether they seek to carry on what came before them. They will never know what it is like to grow up without a father, just like I never knew what it was like to grow up with a father. But they will not have to go searching for what was to be theirs by birth, like I have—like every kid raised without a father has.