Life, Liberty, Property #122: New York State of Confusion

Forward this issue to your friends and urge them to subscribe.

Read all Life, Liberty, Property articles here, and full issues here and here.

IN THIS ISSUE:

- New York State of Confusion

- Video of the Week: Zohran Does New York – In the Tank #518

- Tax Wealth, Get (Lots) Less of It

- Nondelegation Without Chaos

Hot off the presses! Our latest Best-Seller

New York State of Confusion

Zohran Mamdani, the newly elected mayor of New York City, ran a strong campaign focused on economic issues, especially the city’s much-discussed affordability crisis. Mamdani promised to distribute a wide variety of benefits to struggling New Yorkers by taxing “the wealthy,” a process that seldom goes according to plan.

“Mr. Mamdani is asking for a lot,” report Grace Ashford and Benjamin Oreskes at The New York Times. Mamdani’s ambitious program includes “proposals to freeze the rent, make buses fast and free, and make child care available to all New York families.”

Mamdani will need enormous tax increases to cover his ambitious plans, the NYT reporters note:

Mr. Mamdani is asking for a lot. Expanding child care to cover children as young as 6 months could cost between $5 billion and $8 billion, by his team’s calculation. Extending the policy statewide could easily cost twice that much.

The mayor-elect has proposed a new two percentage point tax increase on residents making more than $1 million a year, which Mr. Mamdani says would net about $4 billion annually. The increase would raise the city income tax on the wealthy to about 5.9 percent from about 3.9 percent.

Under that scenario, an individual making $2 million a year who pays roughly $77,000 in city income taxes could pay $117,000—a roughly 50 percent increase.

Those tax hikes would greatly raise the cost of living in New York City for Mamdani’s proposed revenue generators, without increasing the quality-of-life improvements they presumably receive in return for their tax payments. The only people in that group who will not consider the tax hikes an excessive imposition are those who greatly enjoy having government decide on what charitable giving they do, and those who are so wealthy that they can haughtily reply, “‘Tis but a scratch!”

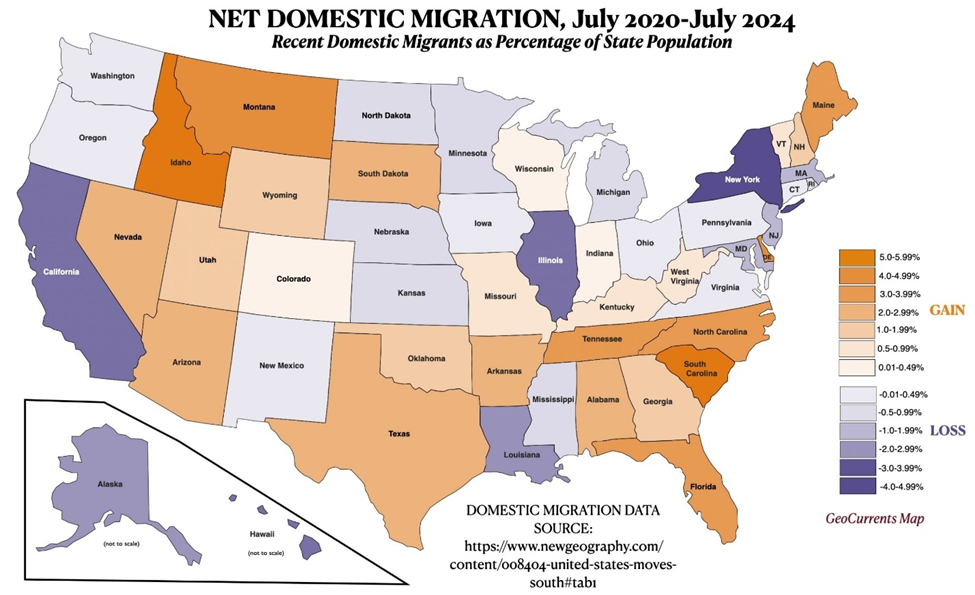

Given the ongoing emigration from New York to other states, an increase in the number of people fleeing the city and the state seems extremely likely. “Some business leaders and economists have argued that such an increase would lead people to decamp to Connecticut or Florida,” the NYT reporters note.

In a poll released on the day before the election, hundreds of thousands of New York City residents said they were already planning to move if Mamdani was elected, and more than two million others said they would consider doing so, the New York Post reported:

Around 765,000 people of the 8.4 million residents who call New York City home are preparing to leave, with about 9% of New Yorkers sharing that they would “definitely” leave the city if Mamdani is elected the 111th mayor, the Daily Mail reported, citing a survey conducted by J.L. Partners. …

Another 25% of New Yorkers—about 2.12 million—said they would “consider” packing up and leaving.

Among high earners, 7% of those making over $250,000 a year said they would definitely flee.

Although the number of people who will leave will surely be well below those numbers, 884,000 have moved out of the state in the past five years. The proposed taxes would surely increase that outflow.

Gov. Kathy Hochul, in a tight reelection race with Rep. Elise Stefanik, is understandably reluctant to take responsibility for a massive depopulation of the nation’s largest city, a crash in state tax revenues, and a fiscally debilitating increase in the state’s ratio of tax consumers to taxpayers. All of this would simply destroy the state government’s budget.

Hochul is in fact rather peeved about the prospect, the NYT reports:

Ms. Hochul even signaled the depth of Mr. Mamdani’s challenge on Thursday evening when, speaking before a crowd in San Juan, she was interrupted for the second time in two weeks, with calls to “Tax the Rich.”

“I hear you,” Ms. Hochul said, then quickly offered a warning: “I’m the type of person—the more you push me, the more I’m not going to do what you want.”

New Yorkers are increasingly saying the exact same thing.

Sources: The New York Times; New York Post

Video of the Week

On Tuesday, New York City elected a trust-fund communist as mayor. New Jersey, which seemed to be trending red, put a scandal-ridden Democrat in the governor’s mansion. In Virginia, voters rejected a black Republican conservative woman over a woke former CIA spook who pledged to force girls and women to endure biological men in their private spaces again. Oh, and Dems in the Old Dominion also elected a man who wished a political opponent and his children would be murdered so his grieving wife would finally agree with him on policy as she held her family in her arms.

Tax Wealth, Get (Lots) Less of It

Californians may vote next year on whether to tax the wealth of the state’s billionaires—not just their incomes, consumption, land and homes, realized capital gains, real estate transactions, inheritances, and so on. “The proposed ballot initiative would levy a one-time, 5% tax on the approximately 200 billionaires in the state, generating roughly $100 billion in revenue, according to proponents,” Cal Matters reports.

The proposed tax would slice off one-twentieth of each billionaire’s overall wealth. “Instead of targeting earnings, the state would levy such a tax on the net worth of an individual, everything from investments to property value and even other assets, like jewelry and paintings,” the article reports.

Labor unions and health care groups are behind the proposed ballot initiative, the site reports:

Service Employees International Union-United Healthcare Workers West and St. John’s Community Health in Los Angeles want voters statewide to approve a “billionaires tax” to help prop up the state’s health care and education systems. …

Going to the ballot is a common move for advocacy groups frustrated with Sacramento politics, which, while dominated by Democrats, can still be factious. Dave Regan, president of SEIU-UHW, said at a news conference the ballot initiative is the “only solution anyone can see.”

Nearly all the money would go toward government health-care spending, with some being used to increase funding of government-run public schools: “The revenue would go into a special fund with 90% reserved for health care spending and 10% reserved for K-12 education spending,” the story states.

The state legislature has never passed a wealth tax, casting doubt on whether the public will support the referendum if it makes the ballot, as appears to be likely, the site reports: “While California has taxed the income of millionaires, lawmakers have never successfully passed a wealth tax.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom opposes the idea:

The governor is a big reason why. Newsom has never supported a wealth tax, at times angrily rejecting conservative efforts to link him with one as “shameful.” He quashed the most recent legislative effort last year.

Meanwhile, Illinois lawmakers considered imposing a wealth tax through legislation in the recently concluded session. The Illinois Policy Institute (IPI) reports,

As part of a plan to generate $1.5 billion for the Regional Transit Authority and close its $200 million budget gap, lawmakers propose a first-of-its-kind “billionaire tax” which would tax unrealized gains on assets at 4.95%, equivalent to the state’s flat income tax rate.

Taxes on gains in wealth are customarily imposed when one sells the asset, as the sale establishes the precise amount of the gain and ensures that the individual being taxed has the liquidity to pay the levy (through the revenue on the sale). The wealth tax, by contrast, would require billionaires to pay on appreciation of assets they do not sell. The IPI reports:

Currently, capital gains which include assets such as stocks, real estate or private business shares are taxed only when they are sold and income is realized. Under this new proposal, Illinois residents with net assets exceeding $1 billion would calculate the market value of these assets each year and pay a 4.95% tax on the appreciation.

Losses on capital gains would not be recognized in that taxable year but would be able to be carried forward indefinitely.

The proposed tax would probably violate the state’s constitution, the IPI article states:

The Illinois constitution explicitly prohibits taxation of personal property, including non-tangible assets such as stocks, bonds and patents. Supporters are calling this proposal an “income tax” by arguing that on-paper increases in capital gains count as “economic income,” even though no money changed hands. This is in theory, not a reflection of what the word “income” means, whether in common usage or by tax professionals. …

The tax also runs the risk of double taxation which is also prohibited under the Illinois constitution. Double taxation happens when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income. The tax would apply to the income that is used to buy assets, when those assets accumulate value, to finally when those assets are sold, creating a sequential taxation on the same income stream.

The legislature dropped the tax proposal in the last day of the fall veto session. Look for it to return next year, however.

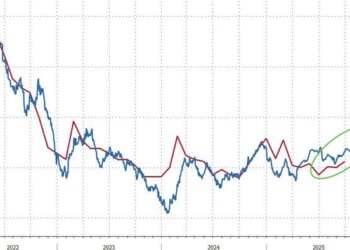

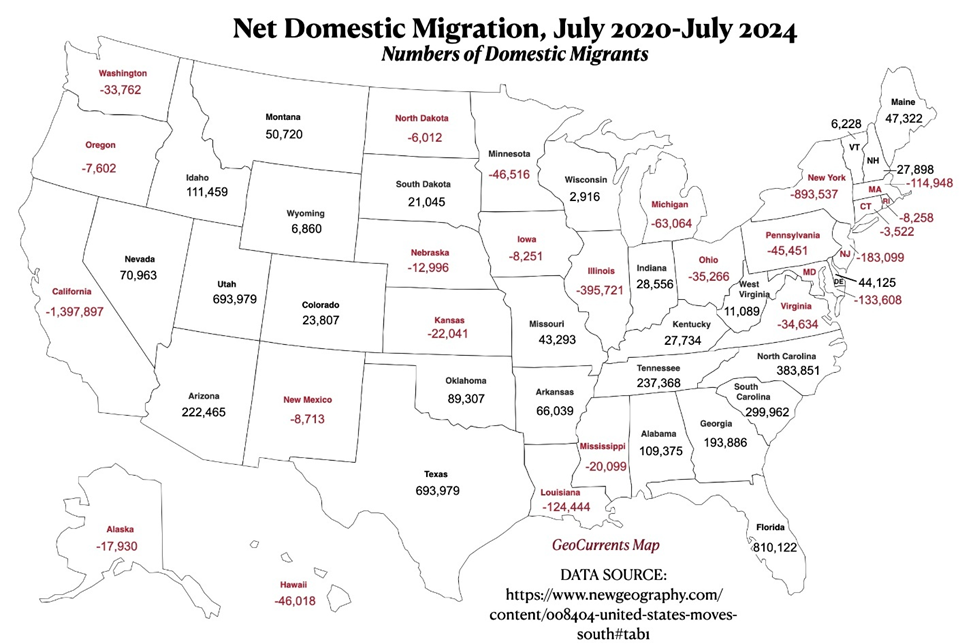

By chasing away the people with the most money to invest, a tax on unrealized incomes would accelerate the already rapid exodus out of high-tax states such as California, Illinois, and New York to lower-taxed jurisdictions:

Source: GeoCurrents

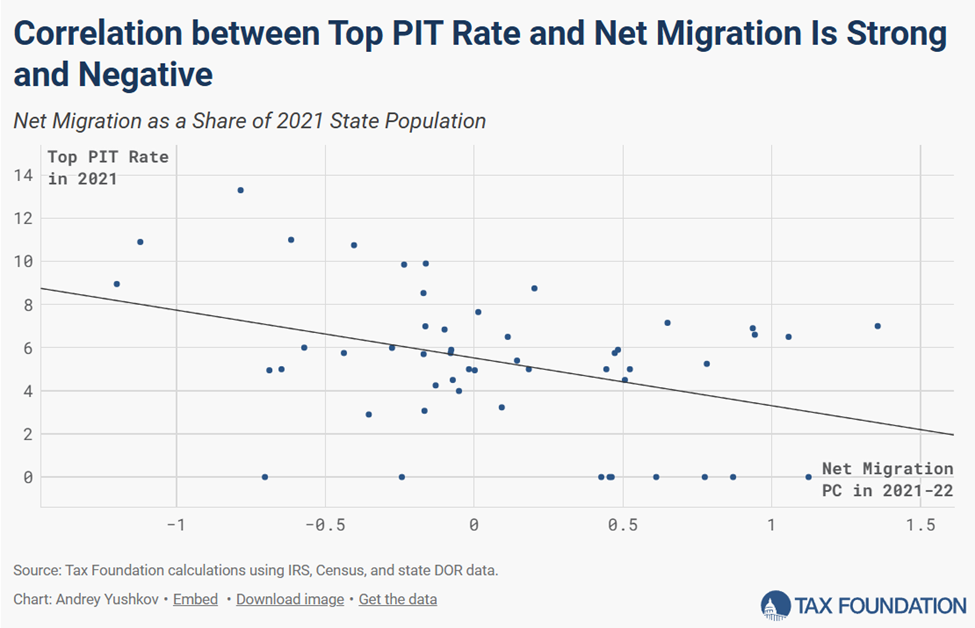

Source: The Tax Foundation

The wealth-tax-induced exodus would also reduce revenues from other taxes in the state, of course. Tax Foundation Vice President Jared Walczak writes,

Such a highly complex, costly tax will undoubtedly change behavior, with the Joint Committee on Taxation noting that capital gains are particularly sensitive to taxation. And one behavior we’d expect to see in Illinois at a much greater rate than if such a tax were adopted by the federal government: moving out. If unrealized capital gains are to be taxed year after year, that could easily drive some of Illinois’ wealthiest taxpayers out of state—depriving the state of their existing income tax payments (including on capital gains), along with other taxes they remit, to say nothing of their impact on the state’s economy more broadly.

A wealth tax, if upheld by the courts as constitutional, would be a great way to reduce the net wealth of a state.

Sources: Cal Matters; The Illinois Policy Institute; The Tax Foundation

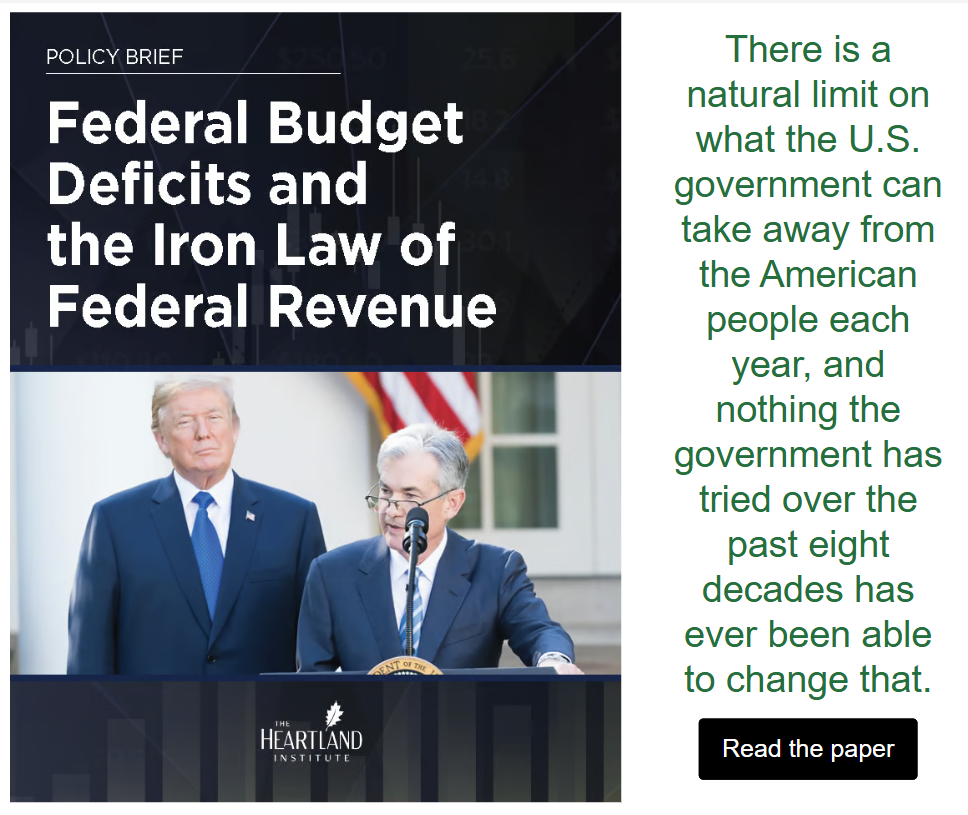

NEW Heartland Policy Study

‘The CSDDD is the greatest threat to America’s sovereignty since the fall of the Soviet Union.’

Nondelegation Without Chaos

The foundation for the administrative state is Congress’s delegation of rulemaking authority to Executive Branch agencies. This delegation allows executive agencies to make vast, major policy choices in interpreting often-deliberately vague and broad authorizations in federal statutes.

“Such broad delegation threatens to make the executive the lawmaker by giving over to that branch the essential policy choices the Constitution entrusts to Congress,” writes Northwestern University professor John O. McGinnis at Law & Liberty.

In the past two decades, the U.S. Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Roberts has steadily moved to restore the distinction between the legislative and executive branches through multiple decisions that confine legislative choices to Congress. Under the “nondelegation” doctrine, “Congress is to legislate; the president and his subordinates are to execute within a hierarchical, accountable executive; and courts are to exercise independent judgment in interpreting the laws,” McGinnis writes.

The Roberts Court, however, has not made nearly as much progress on restoration of the nondelegation doctrine as in other areas of its administrative-state rollback, McGinnis observes. This is a case of judicial conservatism, not originalism. Americans have adjusted their actions to the current, century-long system of administrative rule, and major changes to that arrangement would create huge transition costs, McGinnis writes:

The principal problem is that revising the delegation doctrine would implicate vast reliance interests and generations of precedent in a way that could create a regulatory vacuum. The “intelligible principle” line has long permitted capacious grants that agencies have used to build the basic architecture of federal regulation. Overruling that settlement would endanger a large number of administrative delegations in environmental, consumer protection, and other areas of regulatory law.

The fact is that modern government is administrative government, and delegation has been its lifeblood. Under the authority of these delegations, the federal government has issued hundreds of thousands of pages of regulations. In the recent case of FCC v. Consumer Research, for instance, the Court raised concerns about past delegations even when refusing to overturn the application of the intelligible principle test to a much narrower class of legislation that delegates taxing power to agencies.

The Roberts Court has deployed a substitute doctrine to do some of the much-needed restoration of the nondelegation principle, establishing the “major powers” doctrine “requiring Congress to ‘speak clearly’ before assigning agencies authority to decide matters of vast economic and political significance,” McGinnis notes. The major powers doctrine, however, supports the delegation doctrine and makes it less likely that the Court will fully remove it, McGinnis writes:

But the major questions doctrine’s effectiveness as a shadow doctrine may shore up the status of the delegation doctrine, even if it is the administrative state’s most substantial distortion of the constitutional separation of powers. For instance, Justice Kavanaugh relies on the presence of the major questions doctrine in his Consumers Research concurrence as a reason to accept the majority’s application of the intelligible principle test for the delegation doctrine. Thus, one problem with doctrines created by the “hydraulic pressures” mentioned by Gorsuch (rather than those compelled by a formal reading of text) is that they may lessen the pressure for more substantial course corrections even when justified.

McGinnis offers an alternative approach that he and Michael Rappaport (his coauthor on the 2013 book Originalism and the Good Constitution) have developed, called prospective overruling:

Is there a way to restore a stricter nondelegation regime without disturbing the vast network of statutes and regulations built on more permissive doctrines? Rappaport and I have defended a concept—prospective overruling—that, when applied to delegation, offers a disciplined way to do just that. Prospective overruling mitigates those reliance costs while putting the Constitution on a glide path back to its original meaning.

In a case squarely presenting the issue, the Court would announce the governing standard: Congress must make the policy choices; administrators may implement the law and find facts. In subsequent cases, future delegations would then have to conform to that rule. Existing statutes, however, would remain enforceable, creating a safe harbor for preexisting delegations and the regulations issued under them. The virtue of this two-step is that it would apply the original meaning to a single, recent enactment rather than to numerous statutes enacted over a lengthy period, thereby minimizing reliance costs while reestablishing the proper separation of powers.

The contrast with retrospective overruling underscores why prospectivity is the sounder course. If a stricter delegation rule were applied to the past, Congress would face enormous pressure to replace, in short order, a sprawling body of law—an institutional task made harder by both the sheer quantity of provisions to review and the strategic behavior that inevitably attends omnibus renegotiation. By contrast, prospective overruling leaves no regulation under a current delegation vulnerable to immediate invalidation; it channels change through ordinary legislative time, allowing Congress to transition one statute at a time, with notice of the constitutional standard that now governs.

Prospective overruling also encourages Congress to develop practical institutional responses consistent with the new constitutional framework. Legislators can choose to write more determinate statutes that they prefer, however, to empower expert agencies. They can then instead require that major rules obtain fast-track legislative approval before taking effect, thus ensuring that elected representatives, not administrators, make the ultimate policy choices. Congress can also build advisory capacity, such as its own regulatory advisory units, to inform those more specific choices. By putting Congress on notice and giving it time, prospectivity reduces the reliance of both individuals and governments while re-anchoring delegation in the Constitution’s original design.

I do not know how much disturbance a full, immediate return to the nondelegation doctrine would cause. It seems plausible to accept the notion that it would make quite a mess of things for a while. With that in mind, prospective overruling would certainly be a great improvement over the Court’s longtime acceptance of the delegation doctrine. A “glide path” to the Constitution’s original meaning is certainly better than a patchwork repair through the major questions doctrine which a new court majority could dismantle in a flash.

Of course, that’s the problem with any good decisions that the Supreme Court makes.

Source: Law & Liberty

Contact Us

The Heartland Institute

1933 North Meacham Road, Suite 559

Schaumburg, IL 60173

p: 312/377-4000

f: 312/277-4122

e: [email protected]

Website: Heartland.org