And the signs are concerning:

- The median sales price for homes sold in 2024 was about $415,000, a nearly 50 percent increase from a decade earlier, according to data from the Census Bureau and Housing and Urban Development Department (HUD). (The consumer price index—a standard inflation metric that measures price changes for a particular basket of goods and services over time—only increased by a third during the same time period.)

- The median age of a first-time homebuyer is 40 years old (up from 38 in 2024). In the 1980s, the median age of first-time homebuyers was under 30 years old.

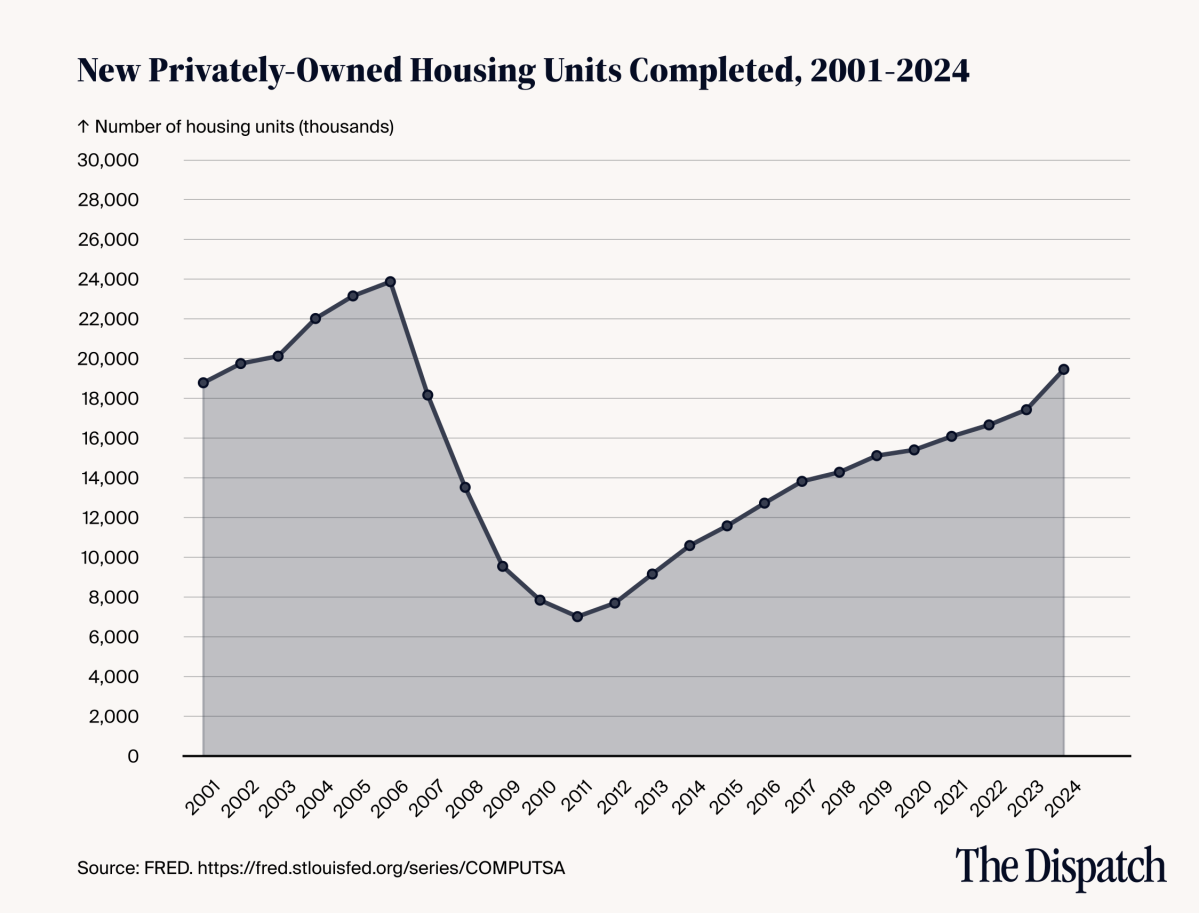

- In 2024, the U.S. built approximately 19.5 million privately owned housing units—down nearly 20 percent from a peak of 23.9 million units in 2006.

- The estimated number of housing units rose by only 9.2 percent between 2014 and 2024—whereas inventory increased by 18.9 percent between 2004 and 2014.

- The number of new single-family homes constructed annually fell nearly 50 percent between 2005 and 2024, from just under 1.3 million units to 686,000, according to data from the Census Bureau and HUD.

In short, there are fewer houses than ever, at higher prices than ever, bought by older people than ever before. “If you were about to buy a house four years ago and you didn’t … if you weren’t quite there, what this is telling us is you are now further behind,” Salim Furth, a research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, told TMD. “The housing market is getting out of reach faster than people are aging.”

A 2021 study commissioned by the National Association of Realtors (NAR)—a real estate trade group—estimated a national housing shortage of 5.5 million units, citing data from the Rosen Consulting Group and several Census Bureau surveys, based on the difference between the number of residential units completed each year and the annual long-term average. More recently, in November 2024, Freddie Mac estimated a 3.7 million-unit housing shortage, using numbers from the Census Bureau’s quarterly Housing Vacancy Survey.

While broader economic and societal trends affect housing prices and availability, various barriers have hindered the construction of new houses. The problem isn’t found in a few specific statutes, but rather in the layers of regulations that developers must review and comply with before pursuing any housing project, like zoning laws, permitting and licensure requirements, parking mandates, property setbacks, building codes, and height limits.

“The adoption of zoning started in the 1910s in a few parts of the U.S., and really took off during the 1920s,” Emily Hamilton, a Mercatus Center senior research fellow, told TMD, “but there’s been an ongoing … build up of all kinds of regulations, making it harder to build housing over the whole last century.” She continued: “Over the decades, localities have added … design reviews or historic reviews or environmental reviews that add to the time it takes to get permission to build housing and add costs and reduce supply as a result.” And then there’s just the willingness to approve certain changes.

“It’s perfectly kosher today to tear down a gas station to build a residential building,” Issi Romem—an economist and founder of MetroSight, a firm specializing in housing and urban economic research—told TMD. “What’s not kosher is tearing down housing, especially single-family housing, and building anything denser in its place.” This leads to “islands of density,” where certain pockets may develop more multifamily units, but other areas rarely see increases in housing units per acre.

Romem pointed to the California Energy Commission’s 5-0 vote in 2018 that required all new homes constructed in the state to include solar panels beginning in 2020. “There’s a benefit to that,” Romem said, in terms of clean energy production, but “there’s also a cost to it, and there’s a trade-off to be had between affordability and environmental protection.” He added, “There’s probably not nearly enough awareness among those who write the building code in terms of what that does to affordability.”

Zoning ordinances, such as minimum lot size requirements, suppress housing supply by ensuring fewer units are built on developers’ properties. M. Nolan Gray broke down the issue in a June 2022 article in The Atlantic:

To see how this works, imagine a three-acre plot of suburban land. Let’s assume that regulations require a quarter of it to be set aside for streets and a small park—fair enough. After a market study, a developer finds strong demand for homes on 5,000-square-foot lots. The size of the plot should allow her to develop 19 such homes, but there’s a snag: Local code imposes a minimum lot size of 7,500 square feet. Thus, she can build only 13 homes, all of which must be more expensive to cover the land costs. At best, the community is left with 13 expensive homes. At worst, this market can’t yet sustain the higher price point, and no homes are built.

Rising input costs for construction materials and labor also contribute to higher home prices.

“I think maybe the thing that people might underestimate is just how many other components in housing might be imported and subject to tariffs,” Jake Wegmann, an associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin, told TMD. Both the first Trump White House and the Biden administration raised tariffs on core housing construction materials, including steel, aluminum, lumber, and timber.

In his second term, Trump has imposed additional tariffs on all those materials—plus others, including copper—and his crackdown on illegal immigration has exacerbated labor problems. According to an October 2024 report from the Pew Research Center, unauthorized immigrants accounted for 24 percent of construction workers.

More recently, on Saturday, Federal Housing Finance Agency Director Bill Pulte tweeted that he and Trump were working to provide 50-year mortgage opportunities for homebuyers. However, David Bahnsen, founder of the Bahnsen Group wealth management firm, noted this proposal “has nothing to do with new supply, which is the lowest hanging fruit for affordability, and it forgets that a lower monthly payment gets efficiently priced into the sticker price of the house.”

Making housing affordable requires building more housing. “There’s no way to win the game of musical chairs where everybody gets a seat, unless you’ve added chairs. … Then you can debate these various forms of specific affordability to help specific people out,” Furth explained. But he pointed to a further problem: If officials change a community’s zoning code to permit a higher density of development but also impose rent control, “nothing is going to get built.”

Why? Rent control, like certain zoning restrictions, will lead to slower housing development because it limits how much prospective developers can recoup on their investment. “This is just zoning by another name, where you say, ‘You can’t make any money,” he said.

Housing is becoming more affordable in Austin and Denver, two areas where the respective regulatory structures have allowed developers to more easily build wet utilities—systems that supply water or remove sewage and wastewater. It may be “really boring and puts people to sleep,” Furth added, “but … gosh, you don’t want a house without a sewer, right?”

Alex Horowitz, a project director for housing policy at Pew Charitable Trusts, also praised Austin, noting that the local government passed laws to encourage housing development in the area.

“They’ve cut their permitting times by more than half, they’ve eliminated their parking mandates, they’ve made it much easier to build apartments, they have reduced their minimum lot size to allow starter homes, they’re allowing multiple homes per lot, they update their building code to allow buildings up to five stories that have one stairway instead of mandating two,” he said, “and all of those changes are working together to improve affordability.”