Save the snark and schadenfreude. Sure, Europe’s economic stagnation may look like sweet vindication for American techno-optimists, but it’s nothing to celebrate. The continent’s failure to produce global technology titans or seize the artificial-intelligence moment should serve as both a cautionary tale and a wake-up call. Yes, it exposes the pitfalls of precautionary-principle overregulation and a “big is automatically bad for competitiveness” mindset. Yet America has no interest in a weak, inward-looking Europe. As the U.S. faces an authoritarian coalition stretching from Moscow to Beijing, it needs a revitalized, innovative Europe at its side—not one that can’t build or defend.

For a time, many progressive policymakers and activists here at home saw Brussels as the north star of digital regulation. Over the past decade, figures like Lina Khan and Tim Wu drew inspiration from the European Union’s sweeping privacy and competition regimes—such as the GDPR and, later, the Digital Markets and Digital Services Acts—seeing them as proof that liberal democracies could and should rein in Big Tech by law rather than markets. The European Way promised fairness, accountability, and safety. Instead, it delivered bureaucracy, compliance headaches, and economic drift.

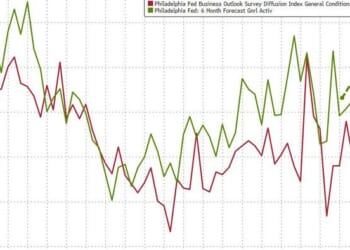

This is a devastating chart, via the Financial Times:

Bottom line: Europe’s regulatory zeal has throttled innovation while leaving it strategically and technologically dependent on others. The EU is proposing to pause or water down parts of its landmark Artificial Intelligence Act—a tacit admission that it overshot—marking its first flicker of pragmatism. The reform would grant companies a one-year grace period and delay fines until 2027, acknowledging that smothering startups with rules is no substitute for dynamism. It’s a welcome shift, but an alarmingly late one. The U.S. and China are already pulling far ahead in AI, cloud computing, and advanced chips.

Europe’s troubles run deeper than a series of bad laws tinged with degrowth thinking. As Financial Times columnist Martin Wolf argues, the continent’s historic “competitive fragmentation” once powered the Industrial Revolution. But in a world dominated by continental superpowers, that same diversity now prevents Europe from scaling new technologies or mobilizing resources for defense. The European Union has 450 million people and a vast economy, yet it lags badly in productivity and risk capital. Completing the single market, integrating energy and defense, and embracing risk are no longer optional. They may be matters of survival.

From that piece:

… economies of scale, scope and, above all, agglomeration play a huge role in the most advanced modern technologies. It is surely no accident, as Paul Krugman notes, that the digital revolution has been concentrated in Silicon Valley. Would Europeans accept (or be able to engineer) such a supercluster? One has to doubt it. If so and if, too, this bears not just on productivity, but also on the ability to defend its security, then the conclusion might be that Europe now suffers from a paradox of its history: the fragmentation that made its states powerful and rich is, in the new world, a barrier to their remaining so. In an age of continental-scale superpowers, European fragmentation may be an insuperable handicap.

The United States has a direct stake in pro-growth European transformation. As AEI scholar and historian Hal Brands told me on a recent Political Economy podcast, the contest with China is a Eurasian struggle over scale—industrial, technological, and ideological. America cannot meet that challenge alone. A Europe that gets its economic act together would be a tremendous strategic asset. It would be a partner able to innovate, rearm, and share the burden of sustaining a free and prosperous order.

We should hope that Brussels’ pause on its AI rulebook really does mark the first crack in years of defensive policymaking, with more to come. If it signals a broader shift from moral grandstanding to maximizing competitive intensity, Americans should cheer—not jeer. The free world’s future may depend as much on a Europe that builds as on an America that leads.

The post Europe’s Slowdown Is America’s Problem, Too appeared first on American Enterprise Institute – AEI.