Welcome to Dispatch Energy! President Donald Trump has on multiple occasions committed to refilling the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) “right to the top,” but thus far hasn’t managed to secure the funds from Congress to do so. There is also plenty of debate about how full the SPR should be, given that its original purpose—namely, to cover for America’s massive net oil import dependence—has faded in importance following the shale revolution and the United States’ shift to being the world’s largest petroleum producer and exporter.

Strategic Petroleum Reservations

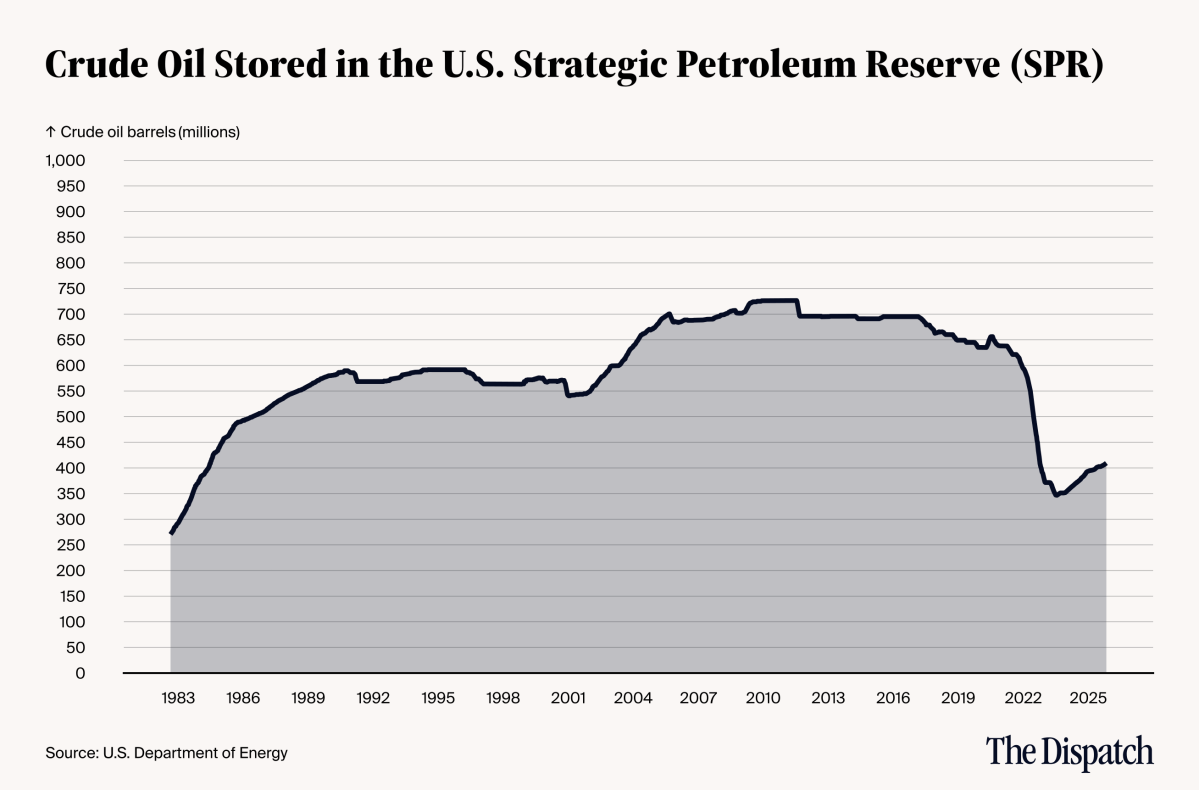

The SPR hit a four-decade low in mid-2023—at 347 million barrels, or less than half the reserve’s capacity—and today stands at 410 million barrels or 57 percent of the SPR’s 714 million barrel authorized capacity. This pool of presidentially controlled crude oil is a strategic asset, but also an internationally agreed-upon reserve squirreled away in case of emergency. At current prices, it would cost the Trump administration more than $18 billion to refill the SPR completely to the brim.

However, America’s strategic requirements for the SPR have greatly evolved since its establishment in the 1970s. The reserve’s modern-day purpose—and potential—is muddied. Without a clear vision from the White House and the Department of Energy, it’s all but guaranteed that the SPR won’t be used to its fullest potential. The reserve holds the potential to be a unique and strategic tool if used bi-directionally—as both seller and buyer of last resort—rather than viewed as a battery, where the main value is in the ability to simply extract energy when needed.

Inspired by your comments on my first newsletter, let’s review the SPR’s historic context and consider whether it should continue to serve its original purpose a half-century on from the reserve’s initial conception.

Historical impetus.

The SPR was born out of the oil price shocks of the 1970s. In other words, the U.S. SPR, from its founding, was meant to buffer against economic harm caused by oil market shortages and price spikes—and, contrary to the frequent tone of debate around the SPR, the reserve is not meant primarily to buttress military preparedness.

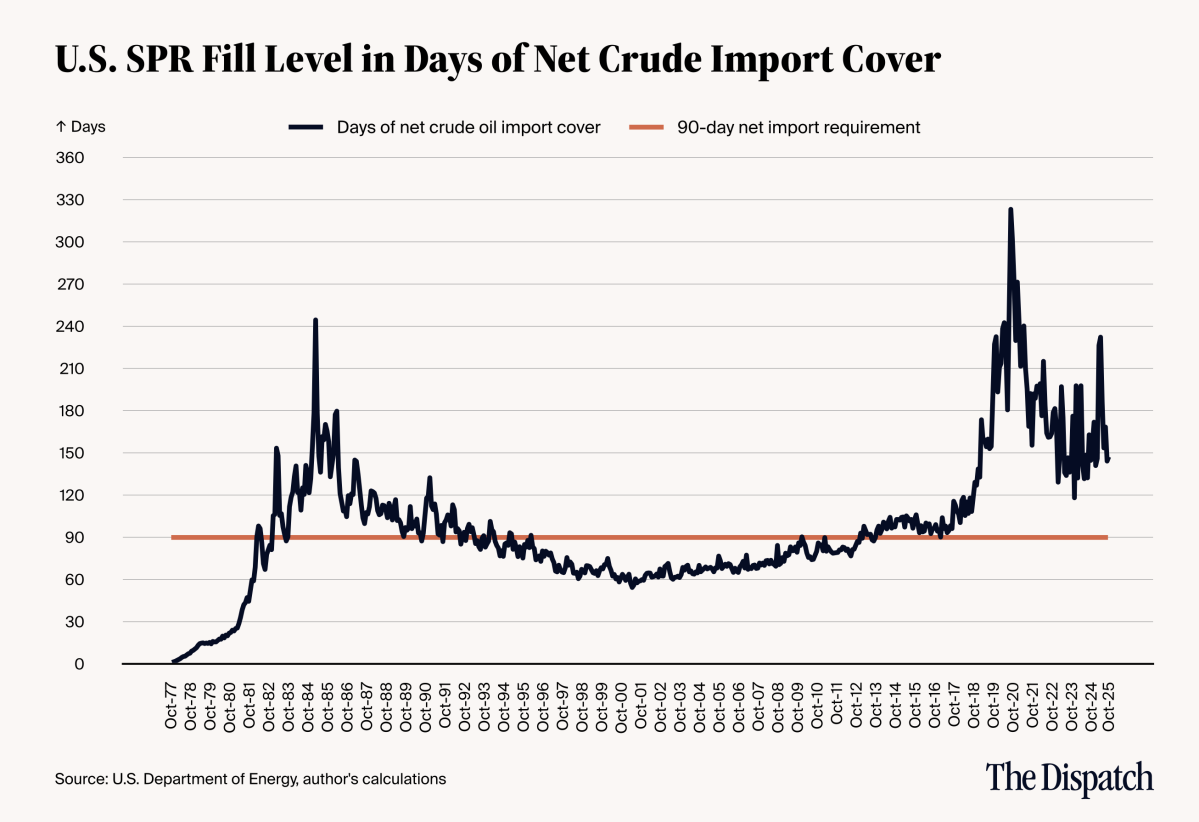

In 1974, member states of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the club of high-income countries including the United States, signed the Agreement on an International Energy Program (IEP) in the wake of a 1973 Arab oil embargo on the U.S. and a handful of other buyers. The IEP, which today includes 32 nations worldwide, requires that participating countries “hold stocks equivalent to at least 90 days of their net oil imports.”

While the IEP did allow some flexibility in what could be counted toward those reserves, the U.S. took the most direct path: the creation of a giant, presidentially controlled reserve of crude owned outright and operated by the DOE. The reserve today consists of roughly 60 underground salt caverns spread across four sites, two in Texas and two in Louisiana.

Drawing down.

Historically, most withdrawals from the SPR have been relatively modest. The reserve has most commonly been used to help offset hurricane-related disruptions to crude production in the Gulf of Mexico, and most such releases have taken the form of “exchanges” of a few million barrels, wherein the recipient was required to return the crude to the reserve at a later date. There were only three “emergency releases” before 2022: Desert Storm (1991), Hurricane Katrina (2005), and the first Libyan War (2011). The average amount released in each of those emergencies was around 20 million barrels—a marginal impact on stocks.

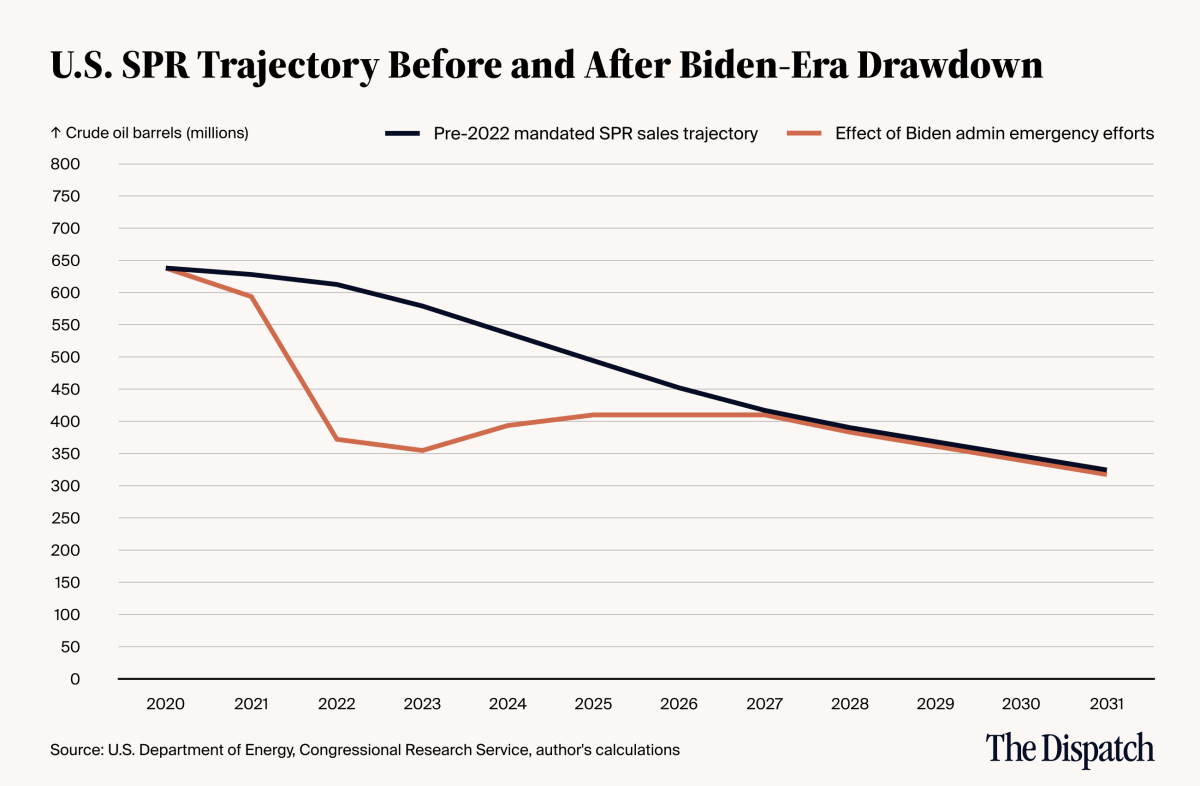

Then, in March 2022, the Biden administration announced an unprecedented 180 million barrel emergency release to serve as a “wartime bridge” as global producers sought to ramp up output in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The conflict’s start threatened to squeeze already-tight global markets: As I explored last month, producers struggled to meet resurgent demand following the COVID pandemic. Against that backdrop, the International Energy Agency warned that the global market would lose 3 million daily barrels (roughly 30 percent) of Russia’s oil supply.

This geopolitical tumult rapidly translated into pain at the pump. The price of U.S. benchmark West Texas Intermediate crude spiked to more than $120 per barrel and gasoline retail prices soared to record highs of more than $5 per gallon. Record-high pump prices would be politically unpopular in any year, but especially at a moment when inflation across all other sectors was surging. The U.S. Federal Reserve, which normally excludes volatile food and fuel prices when assessing price stability, fretted about rising inflation projections driven in large part by sky-high pump prices. Meanwhile, opponents of President Joe Biden’s emergency release decried it as a craven attempt to buy off voters ahead of the midterm elections that year—a charge repeated by Trump’s energy secretary, Chris Wright, earlier this year.

To draw down the reserve, the secretary of energy needs a presidential finding that the sale is “required by a severe energy disruption or by obligations of the United States under the international energy program.” And, arguably, the March 2022 release did meet the specific legal requirements: 1) “an emergency situation exists and there is a significant reduction in supply which is of significant scope and duration,” 2) “a severe increase in the price of petroleum products has resulted from such emergency situation,” and 3) “such price increase is likely to cause a major adverse impact on the national economy.”

If there’s a criticism to raise about Biden’s withdrawal, it’s regarding timing and execution rather than initial justification. Arguably, the release was maintained for longer than the risk warranted; crude prices fell back rapidly from $120 per barrel in June to less than $80 by the end of September but aggressive releases continued through December. Changing course partway through a historically large release may have been simply too much for the SPR’s bureaucratic processes, and the policy inertia would have been difficult to turn. But the question of whether the conveniently timed November midterms also factored in remains an open one. It would also be entirely fair to criticize the 32 million barrel exchange the Biden administration announced at the end of 2021, months before Russia’s invasion, with little more justification than uncomfortably high prices.

Target threshold.

In stark contrast to America’s acute oil import dependence when the SPR was created, the U.S. today is now an exporter of more than 2 million daily barrels of crude oil and petroleum products. On that basis alone, the reserve is no longer required in any form—at least in theory. The IEP requires full coverage of import dependence for 90 days. When the SPR was first conceived, the U.S. was a net importer of roughly 6 million barrels of crude oil and petroleum products per day, so it required a reserve of some 540 million barrels. The U.S.’s import dependence rose to an all-time high of about 12.5 million daily barrels in 2005 (requiring some 1.1 billion barrels of import cover) but collapsed in the face of the shale revolution, which has propelled U.S. domestic production growth—and slashed imports—over the past 15 years. The U.S. became a net petroleum exporter in 2019, a position that has only grown steadily since.

But to assess reserve sufficiency, it may be more prudent to look at U.S. net imports of crude oil specifically, because that’s what’s contained in the SPR. This framing changes the broader strategic picture, because while U.S. crude exports have indeed risen, the boom in total U.S. petroleum production has also been driven by natural gas liquids like propane, which are largely extracted from natural gas processing. So despite being the world’s largest petroleum producer, the U.S. is still a net importer of roughly 2.5 million barrels a day of crude oil, requiring 225 million barrels of import cover. Fortunately, these imports are primarily from Canada, which has been the U.S.’s largest source of oil imports for more than two decades and, today, represents nearly two-thirds of total U.S. crude oil imports at 4 million barrels per day. Excluding these extremely secure (arguably captive) Canadian crude supplies, the U.S. is functionally a net offshore exporter of crude oil.

But the nuance does not end there: The type of crude contained in the SPR also matters. The U.S. currently exports more than 4 million barrels a day of mostly light sweet (i.e., low-sulphur) crude and imports 6.5 million medium-to-heavy, more sour (i.e., higher-sulphur) barrels a day from abroad. This is because the shale revolution produced very light crude oil—traditionally more valuable—but most U.S. refineries, built well before the surge, had invested in equipment for medium- or heavy-sour crudes. One could argue that the SPR should carry, specifically, enough medium crude to cover 90 days of the remaining non-Canadian imports.

It’s relatively straightforward to argue that the size of the SPR should be dramatically reduced, if not eliminated outright. And that’s actually, more or less, exactly what the Trump administration proposed in its 2018 budget proposal to Congress: to reduce the size of the SPR to 270 million barrels and close two of the four SPR sites by 2027. The proposal explicitly justified the reduction by citing the collapse in net U.S. imports, stating that the “path to energy security means enabling more American production and investment, not having the Government store an unnecessarily large amount of oil underground.”

A bi-directional asset.

So, the optimal size of the U.S. SPR, based purely on net import coverage, is likely below where the reserve’s current fill level stands today—but that optimal size is also more than nothing; there’s still value in maintaining some reserve. The SPR remains a unique and strategic asset, and its value goes beyond simply the volume of crude stored in its caverns. At its peak in 2022, the SPR was adding more than 1 million barrels per day to the global market: a volume equivalent to half of Norway’s total output. Even more, the SPR can be used both for emergency sales in a time of supply shortfall as well as a buffer against the pain of an acute bear market driven by oversupply. Aggressively buying crude to refill the SPR during periods of acute market weakness can blunt sharp price collapses, softening economic pressure on the price-sensitive shale patch and reducing the anticipated costs of refilling the reserve.

Therefore, it’s most helpful to think of the SPR’s utility as bi-directional. The reserve has always been seen as a seller of last resort, but it can also serve as a buyer of last resort in moments of especially acute market weakness. And this buying function could be especially important in a world in which the widely anticipated oil glut arrives as expected next year. Under this mode of thinking, the currently empty caverns have their own strategic value because, in order to step into that buyer position, the U.S. needs to have the empty storage space available.

In order to capitalize on this potential, the SPR needs to be better prepared and more insulated from the current congressional clamor to control it. The SPR has been chronically politicized to the detriment of its efficacy, with acquisitions and sales routinely generating more than their fair share of political heat. Indicatively, the Trump administration attempted to buy crude for the SPR in the depths of the 2020 oil price collapse and, despite the measurable benefit of filling the caverns with exceptionally cheap crude and stabilizing plunging prices, Congress killed the plan—Democratic Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer even bragged that the version of the stimulus package passed in the Senate “eliminated [a] $3 billion bailout for big oil.”

An even bigger threat to the future of the reserve comes from Congress treating the SPR like a piggy bank from which to help pay for other spending priorities. Over the past decade, Congress has passed multiple laws that collectively mandated the sale of 358.6 million barrels of crude from the SPR. This type of mandated sale is market blind, selling equally into tight or loose markets.

The Biden administration negotiated a cancellation of 140 million barrels in mandated sales in exchange for $10.4 billion in proceeds (roughly $74 per barrel) from the 2022 emergency sale. Some $2 billion from the process was also sent as a more generic “deficit offset.” The DOE used the remaining funds to repurchase 59 million barrels through the end of 2024 at a lower price than the barrels sold in 2022 ($76 vs. $95 per barrel). This implies a simple “profit” of roughly $1.1 billion off the “trade” and more than triple the cost-savings if we factor in the canceled mandated sales. However, the more important takeaway is the utility that the SPR releases provided to an exceptionally tight 2022 oil market.

In conclusion.

The SPR’s stature has been notably boosted since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, with energy security rising to the top of the policy agenda. The hydrocarbon markets are increasingly tugged back and forth by capricious OPEC policy, U.S. sanctions, and the broader proliferation of geopolitical risks to both the supply and transit of these commodities. Far from the 2018 push for dramatically reducing the size of the SPR, Trump now says he wants to fill the stockpile to its maximum capacity.

At current prices, it would cost more than $18 billion to refill the SPR completely to the brim. All of the funds from the 2022 sale have been 1) used to repurchase crude, 2) returned to Congress in exchange for the cancellation of mandated sales, or 3) used in ongoing maintenance of the reserve. Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act initially envisioned $1.3 billion in funding for SPR crude acquisitions, but that funding was subsequently cut to $171 million in the version of the law passed by the Senate.

Even if the funds were made available, however, the optimal course isn’t to buy the barrels today but rather to wait for a weaker oil market (i.e., when barrels are cheaper and the buying itself helps stabilize the market). The DOE should prepare for opportunistic purchases—like the broadly anticipated 2026 supply glut—by ensuring that the funds will be available, avoiding a replay of the 2020 fight over congressional funding. In addition, the reserve should be more formally shielded from congressionally mandated, market-blind sales to pay for non-SPR priorities.

The U.S. is now the world’s largest petroleum producer, but many politicians speak of the SPR as if America were still living in the energy precarity of the 1970s. Using the reserve to its fullest potential will require that policymakers grapple with our newfound energy-dominant reality and actually have the hard debates about how best to leverage this unique asset into the future.

Hero needed: Fighting New York’s de facto fracking ban

New York sits atop some of the richest natural gas deposits in North America. Yet since 2008, State officials have played regulatory whack-a-mole, banning or blocking every viable method of extraction.

The result: soaring energy prices, shuttered operators, and mineral rights effectively seized—without just compensation. Now we’re looking for New Yorkers ready to fight back.

Policy Watch

- Late last month, the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office on Foreign Assets Control imposed harsh, so-called “blocking sanctions” against Russia’s two largest oil producers, Rosneft and Lukoil, with a wind-down period through November 21. The Trump administration has been saber-rattling for months about getting tougher on Russia’s oil trade as a means of pressuring Moscow into a deal with Ukraine, but this marked the first real escalation of substance and could materially tighten what was a loosening market. There’s still plenty of uncertainty as to how strictly these sanctions will be enforced, but they have already prompted Lukoil to declare force majeure on its crude-producing assets in Iraq. Meanwhile, attempts by Lukoil to sell its non-Russian assets to Gunvor, a multinational commodity trading company, were bluntly denied by the U.S. Treasury, which accused Gunvor of being the “Kremlin’s Puppet.”

- The Canadian government set the stage for conditionally scrapping Canada’s proposed oil and gas emissions cap in the budget published last week. This update made explicit what the Carney government has been hinting at for a while now: Ottawa is open to eliminating the oil and gas emissions cap—which would impose a hard, declining limit on emissions from the oil and gas sector—if both industry and the Western Canadian provincial governments can come to an agreement on provincial emissions regulations and, likely, the “scale” deployment of “technologies such as carbon capture and storage.” Given that Canada is the dominant supplier of crude oil to the U.S., whatever affects the Canadian crude oil production outlook will also drive the relative U.S. dependence on less secure overseas crudes.

Innovation Spotlight

- Sectors across the economy are getting AI facelifts, and the oilfield services (OFS) industry is no exception. Major OFS firms, including Halliburton and Schlumberger, have tripped over themselves adding AI-driven features that promise safer, more effective, and continuously improving drilling performance. At a moment when crude oil prices are under downward pressure, global oil producers are looking to reduce costs; today, that’s increasingly taking the form of large layoffs and efforts to increase the productivity of remaining operators.

Further Reading

- In the era of energy pragmatism, many leaders across South America, including Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, are looking to capitalize on their world-leading offshore oil reserves. Lula recently approved plans by Petrobras, the Brazilian national oil company, to conduct exploratory drilling 500 km (311 miles) from the mouth of the Amazon River. This deep dive by the Financial Times outlines differing visions of fossil fuel development across South America, specifically juxtaposing the strategies of Brazil, which is charging ahead with oil development as a means of financing the energy transition, and Colombia, which has throttled its own domestic fossil fuel industry.

Pacific Legal Foundation has been fighting for freedom since 1973. We sue the government on behalf of farmers, fishermen, teachers, nurses, and entrepreneurs—Americans from every corner of the country and from every walk of life—and we win.