You’re reading Capitolism, Scott Lincicome’s weekly newsletter on economics. Today’s newsletter has been unlocked for all readers. If you’d like to read everything we publish, become a Dispatch member today.

A few months ago, an impromptu trip to my neighborhood wine store turned into an awesome lesson in spontaneous order, American entrepreneurship, and creative destruction. There, I met several small-business owners who were proudly sampling their new products and eager to tell me all about them, their upstart businesses, and the booming local industry to which they belonged. Being a dork, I drank up their stories for almost an hour—and sipped a few samples in the process. The kicker was that these happy folks weren’t selling beer or wine—they were selling THC-infused drinks that’ve become all the rage at local stores, breweries, bars, and restaurants here in North Carolina, thanks to nothing more than consumer interest, good ol’ fashioned American industriousness, and the federal government getting out of the way.

Now, that same government is putting these and many other entrepreneurs out of business—and for no good reason. It’s a lesson in not only how misguided and incoherent government overreach can crush a burgeoning U.S. industry—and its tens of thousands of workers —but also how special interests can triumph over sound policy by draping themselves in the familiar guise of “protecting the children.”

The Hemp Ban and Its Costs

With little fanfare and almost no notice, Congress killed off the burgeoning, multibillion-dollar U.S. hemp industry with a short provision slipped into last week’s bill ending the government shutdown. That provision, championed by retiring Sen. Mitch McConnell and House Freedom Caucus Chairman Rep. Andy Harris, prohibits in one year’s time nearly all hemp-derived products in the United States—not just intoxicating THC drinks and “delta-8” gummies, but almost everything that Congress had only (and probably inadvertently) legalized a few years earlier in the 2018 farm bill.

As our friends at The Morning Dispatch explained last week, the new law caps a product’s total THC content at 0.4 milligrams per container—a threshold so low it bans every lawful intoxicating hemp product sold today. (A typical hemp gummy contains 2.5 to 10 milligrams of THC, while most THC beverages range from 5 to 10 milligrams.) In so doing, Congress will eliminate a new U.S. industry that thousands of American entrepreneurs have spent years building into a significant, legitimate player in the U.S. economy. Estimates vary on the total size of the U.S. hemp industry, but assuming it’s between the $7 billion to $28 billion range that’s been commonly calculated, it’d be roughly the size of the U.S. logging ($13.8 billion), catering ($14.4 billion), bakery ($18.3 billion), graphic design ($19.5 billion), or optometry ($21.5 billion) industries. In other words, this isn’t some niche business catering to a few random stoners—it’s the real deal.

Read The Morning Dispatch Free

We’re taking our flagship newsletter out from behind the paywall this week. If you’re looking for a greater understanding of the biggest stories shaping your world, give The Morning Dispatch a try for free—because insights beat outrage.

Stories We Think You’ll Like

While there’s some disagreement about the industry’s size, everyone agrees on two other important facts about it and the law Congress just passed:

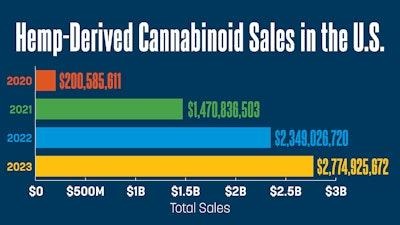

First, hemp-derived intoxicants have seen tremendous growth over the last few years driven by thousands of startups across the country—similar to what happened to the U.S. craft brewing and distilling industries following state and federal efforts to deregulate alcohol sales and distribution. A recent report from the Brightfield Group, for example, projected that THC product sales went from just $200 million in 2020 to $2.8 billion in 2023—an increase of 1,283 percent over just three years. The firm projects THC product sales to have hit $3.5 billion last year and to approach $4 billion this year, with even more (but slower) growth thereafter.

A separate JP Morgan report projected that retail sales of hemp-derived beverages alone would reach $1.4 billion in 2025 and, had the market remained open, would increase almost threefold by 2028 (to $4.1 billion). THC products have also boosted sales at bars and restaurants that now commonly carry them, in part because of demand from people trying to cut back on alcohol. Here in Raleigh, a local magazine reported this spring, you can find THC drinks “at almost any Raleigh bar, bottle shop, brewery or restaurant” because they’ve “exploded in popularity over the last year-plus, with a bevy of local businesses either brewing their own or adding multiple ops to their menus” to meet consumer demand for alcohol alternatives. These drinks and other THC foods are also now sold at bakeries, vape shops, and convenience stores.

It’s clearly a big growth market and clearly something American consumers like and want. And it emerged because the U.S. government simply let Americans—producers and consumers, big firms and small—do business with each other. The miracle of American entrepreneurial capitalism did the rest.

Second, and contrary to defenders of the ban, the new U.S. law will eliminate not only intoxicants but almost all—up to 95 percent—of the multibillion-dollar hemp industry and the 328,000 American jobs now tied to it. (“Even if the federal government largely left states alone when it comes to regulating hemp, as it does with cannabis currently, the ban would create problems that would make the hemp industry virtually unviable, business owners said.”) The law therefore jeopardizes the livelihoods of hemp farmers like the ones in Kentucky who, at McConnell’s own urging, pivoted from tobacco to hemp cultivation; craft brewers like my new friends in North Carolina who took a major investment risk on a brand new venture or pivoted to THC-infused beverages to combat declining beer sales among younger consumers; and many small retailers that now stock hemp products alongside traditional beer and wine. As Whitney Economics notes, the hardest hits will come in states with substantial hemp infrastructure—Kentucky, Texas, Utah, and Minnesota—and to small entrepreneurs like these women who played by the rules, invested their savings, and built safe and legitimate businesses because Congress allowed their industry to come into existence in 2018 and then let it grow over the last seven years.

The ‘Public Health’ Pretext

Proponents justify the ban on public health grounds, particularly child safety, but this claim rings hollow for several reasons. Most obviously, the Cato Institute’s Dr. Jeff Singer explained last week, the ban doesn’t apply to alcohol and other legal intoxicants that are likely more dangerous than hemp-derived THC. Alcohol alone kills approximately 178,000 Americans each year, with crude death rates increasing by almost 90 percent between 1999 to 2024—deaths from not only chronic abuse but also traffic accidents, violence, poisoning, and suicide. As Singer explains, the research on legal THC beverages is limited, but there’s thus far no sign of serious harms. And we know that cannabis is generally safer than alcohol:

Peer-reviewed studies consistently show that alcohol causes much more harm—such as health problems, dependence, and social issues—than cannabis. Two landmark Lancet analyses by Nutt and colleagues, along with later work by Lachenmeier and Rehm, all rank alcohol as the most harmful, with cannabis much lower. However, these studies generally look at cannabis broadly—mainly smoked—and don’t specify whether a 5 mg THC seltzer is safer than a 5 percent beer. They show that, overall, cannabis is less harmful than alcohol; they don’t yet provide specific evidence about today’s THC beverages.

Singer adds that some of the observed risks from THC products are “not unusual” but similar to those for “legal products like alcohol, Tylenol, and energy drinks.” Just as importantly, there’s never been a recorded death from cannabis overdose in adults, and reported “adverse events” from delta-8 THC are rare and minor (though data are, again, limited). The toxicity threshold for children is approximately 1.7 mg of THC per kilogram of a child’s weight, and, while there have been some youth cases requiring ICU admission, they’re managed with supportive care because, unlike alcohol, THC isn’t lethal.

Nevertheless, the risk to children from these products—as well as teen usage—is a legitimate public health concern. A 2024 study in the Journal of American Medicine (JAMA), which claims to be “one of the first nationally representative studies of adolescent use of new hemp-derived cannabis products,” found more than 11 percent of 12th graders had used delta-8 THC in the last year. Another study placed the number a little higher, at 12.4 percent. Risks also arise from young children ingesting edibles that look like candy or other treats, with a few thousand of those cases each year.

This is a problem, but context is important. For starters, far more high schoolers (42 percent of seniors) have tried alcohol, which is more dangerous and—as the current boozy seltzer craze shows—often marketed to young people. States with legalized marijuana, moreover, also deal with children accidentally ingesting gummies and other edibles that look like normal treats. Yet youth marijuana use has consistently fallen over the last decade, even as more states legalized cannabis and hemp-derived THC.

Even more importantly, legitimate concerns surrounding youth exposure to THC products can be addressed via private and public regulation, not prohibition. Here in North Carolina, for example, there’s no age restriction on THC products, but a lot of private businesses have taken it upon themselves to restrict sales to consumers at least 18 or 21years old. Since the 2018 farm bill, moreover, many states have acted to regulate hemp-related THC via comprehensive frameworks that include age restrictions, potency limits, labeling requirements, child-resistant packaging mandates, and restrictions on marketing to children. As of late 2024, only a handful of states had taken no legislative or executive action to regulate hemp products beyond the farm bill.

State-level regulations appear to be effective in curbing underage use. That 2024 JAMA study, for example, found that teen usage rates were much higher in states where delta-8 wasn’t regulated (14.4 percent) than in regulated states (5.7 percent). When states ban lookalike packaging (mimicking popular snacks) and require proper labeling, child safety also appears to improve. And states achieved these results without eliminating, as Singer notes, a “hemp-growing industry that supplies millions of customers with products they enjoy and use for self-medicating for pain, depression, anxiety, and even PTSD.”

Finally, Singer adds, the public health justification for the federal hemp ban contradicts other federal efforts to decriminalize more potent marijuana:

Several lawmakers who claim to support federal marijuana decriminalization—or even full legalization—voted this week for a bill that effectively re-criminalizes many hemp-derived cannabinoids. In the Senate, Dick Durbin (D‑IL) and Tammy Duckworth (D‑WI) supported the motion that maintained the hemp ban language. In the House, Republicans Brian Mast (FL-18), Tom McClintock (CA), and Nancy Mace (SC), along with Democrats Jared Golden (ME), Tom Suozzi (NY), and Don Davis (NC), all longtime supporters of cannabis reform, also voted “yes.” The result reveals a striking example of cognitive dissonance: Congress wants to step back from policing marijuana while simultaneously extending federal control over non-marijuana products from the same plant.

Indeed, the same federal government that just banned hemp products has been actively moving to reschedule marijuana from Schedule I to Schedule III, acknowledging its medical uses and lower abuse potential. The Biden administration initiated this process, and President Donald Trump has indicated support for it, too. In short, much of official Washington believes marijuana—with far higher THC concentrations—is worth championing, but hemp products that typically have lower THC levels are so dangerous they must be banned entirely.

And don’t even get me started on the various federal tax breaks given to the alcohol industry.

Whatever Happened to Federalism?

Indeed, it’s an open question as to whether federal intervention is needed here at all, at least beyond the handful of narrow issues—e.g., online and interstate sales—that have a clear federal nexus. Today, 24 states explicitly allow THC beverages, while 11 have barred them. Regulation in the legal states varies greatly, as it should: A state-by-state approach allows for policy experimentation and local control—exactly what our federal system is supposed to do—while still allowing businesses to satisfy consumer demand. Minnesota, for example, legalized hemp-derived THC edibles in 2023 with a 5-milligram serving limit and comprehensive licensing and safety requirements. Since then, local industry has thrived, contributing $140 million in retail sales while operating under state supervision. Other states, such as Texas and Florida, have imposed tighter restrictions but avoided an outright hemp ban—often after a lengthy policy debate and deliberation entirely absent from last week’s congressional maneuver.

That federal move overrides all these state efforts, preempting regulatory frameworks that took years to develop. Given those harms and all the others, it raises the question of how the ban became law in the first place.

Bootleggers and Baptists, Again

One reason for the ban appears to be that McConnell regretted the effects of his hemp liberalization law and sought to cement his “agriculture policy legacy” by reversing it before he left Congress. Another big motivation, however, is more sinister and unsurprising: good ol’ fashioned economic protectionism.

In particular, the THC ban materialized after intense lobbying from alcohol industry groups and marijuana companies that saw THC products as unwelcome competition. In a November 4 letter to Congress, for example, several major alcohol lobbies—including the Beer Institute, Distilled Spirits Council of the U.S., and the Wine Institute—urged lawmakers to “immediately remove hemp-derived THC products from the marketplace ” because the goods were, unlike alcohol, insufficiently regulated. (They politely offered to “work with Congress and the Administration” to enact THC product regulations—eventually—but only after a full ban was enacted in the meantime.) Third-quarter lobbying disclosure reports, meanwhile, reveal a surge in hemp-related lobbying from Anheuser-Busch, Molson Coors, Bacardi, and other big companies that compete directly with the upstart THC beverage industry. Big Alcohol’s sudden interest in THC products also suspiciously correlates with data showing declining alcohol consumption among young adults and increasing interest in cannabis products from that same demographic.

Big Weed also lobbied for the ban for similar anticompetitive reasons. As Singer notes, “national cannabis trade groups like the U.S. Cannabis Council and the American Trade Association for Cannabis and Hemp, which represent the legal cannabis dispensary industry, have been urging Congress to classify hemp-derived THC products as ‘illegal marijuana’”—and thus to put competing THC firms out of business. Marijuana companies have been doing the same at the state level, including in places like California where more potent marijuana has been legal for years (and where studies show that a THC products ban would impose significant costs to local economies).

In classic “bootleggers and Baptists” fashion, these business groups successfully teamed with anti-drug groups and law enforcement officials to ram through the federal ban with no public debate and despite the problems it needlessly creates. Never mind, of course, that their products raise the same, if not greater, social problems our moral crusaders say they’re worried about—and that banning legal THC products will surely push many consumers and businesses into more dangerous illicit markets. In the end, the cronies got exactly the win they wanted—a competitor removed from the market. Everyone else lost.

Summing It All Up

Barring a major reversal in the next few months, Congress’ shutdown bill will destroy a multibillion-dollar U.S. industry, hundreds of companies, thousands of jobs, and a universe of new products that millions of Americans use for health or recreational purposes. And—given the rapidly evolving regulatory landscape, as well as the wide availability of legal and more harmful alternatives to hemp-derived THC—this thriving industry’s death will occur for no good reason. Congress could’ve just copied the same federalist model of regulation used for alcohol, dietary supplements, and a broad array of foods and medicines. Instead, it opted for prohibition, oblivious to its harms and checkered history.

But, hey, at least Big Alcohol and Big Weed are happy.

The only silver lining here is that there’s still time for Washington to reverse course. THC industry leaders are reportedly planning a comprehensive lobbying effort aimed at replacing the ban with sensible federal regulation before the former takes effect next year. Maybe consumer backlash will also motivate lawmakers to act. Those efforts could keep THC products on our shelves for the long term—and they’ll certainly make D.C. lobbyists happy—but they’ll probably come too late for many responsible small business-owners who just watched their livelihoods get destroyed, not by their by their own hand but by the big, clumsy fist of an indifferent government.

Chart(s) of the Week