Welcome to Dispatch Energy! Representatives from nearly 200 countries around the world—with the notable exception of the United States—gathered in Belém, Brazil, this month for the United Nations’ COP30 climate summit. The location of COP30 has symbolic significance—it was in Brazil in 1992 that the international climate movement was launched at the Rio Earth Summit. But in the years since, including those that followed the forging of the Paris Agreement 10 years ago, carbon dioxide emissions from the burning of fossil fuels have continued to increase along with atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide. So what have these landmark climate initiatives actually accomplished?

The Paris Delusion

In 2015 in Paris, countries from around the world agreed to accelerate the decarbonization of their economies in response to climate change. According to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), implementation of the Paris Agreement over the past decade has been a runaway success story, moving the world away from what would have been a global catastrophe. At the opening of COP30 earlier this month, U.N. Climate Change Executive Secretary Simon Stiell hailed the purported achievements of the initiative:

Over three decade [sic] ago in Rio, humanity set a new course of global climate cooperation. Ten years ago, in Paris, we took a major step forward. Without that act of collective courage, we would still be headed for an impossible future of unchecked heating, of up to 5 degrees. Because of it, the curve has bent below 3°C – still perilous, but proof that climate cooperation works.

The media amplified the victory lap. Take, for instance, CNN’s reporting on the summit:

Ten years ago, humanity was burning so much fossil fuel that Earth was on track to overheat by a catastrophic 4 degrees Celsius by century’s end. But then came Paris, when nearly 200 nations agreed to wean themselves off of oil, gas, and coal; protect more nature; and hold the global warming line at 1.5 [degrees Celsius]. The Paris Accords led to innovation and market forces that now make sun, wind, and storage cheaper and more popular than ever.

The world was headed for a climate apocalypse, and thanks to climate advocacy and an international agreement, the worst has been avoided. We simply need to stay the course to finish the job.

That’s the story that climate advocates and the media are now telling about global climate policy. Unfortunately, that narrative is not rooted in reality. More than 30 years after the Rio Earth Summit, global and national climate policies may have done many things—such as encouraging the redirection of investments toward low-carbon technologies and pushing countries to report on their emissions reduction targets—but accelerating the pace of global decarbonization is not among them, no matter what tall tales are told.

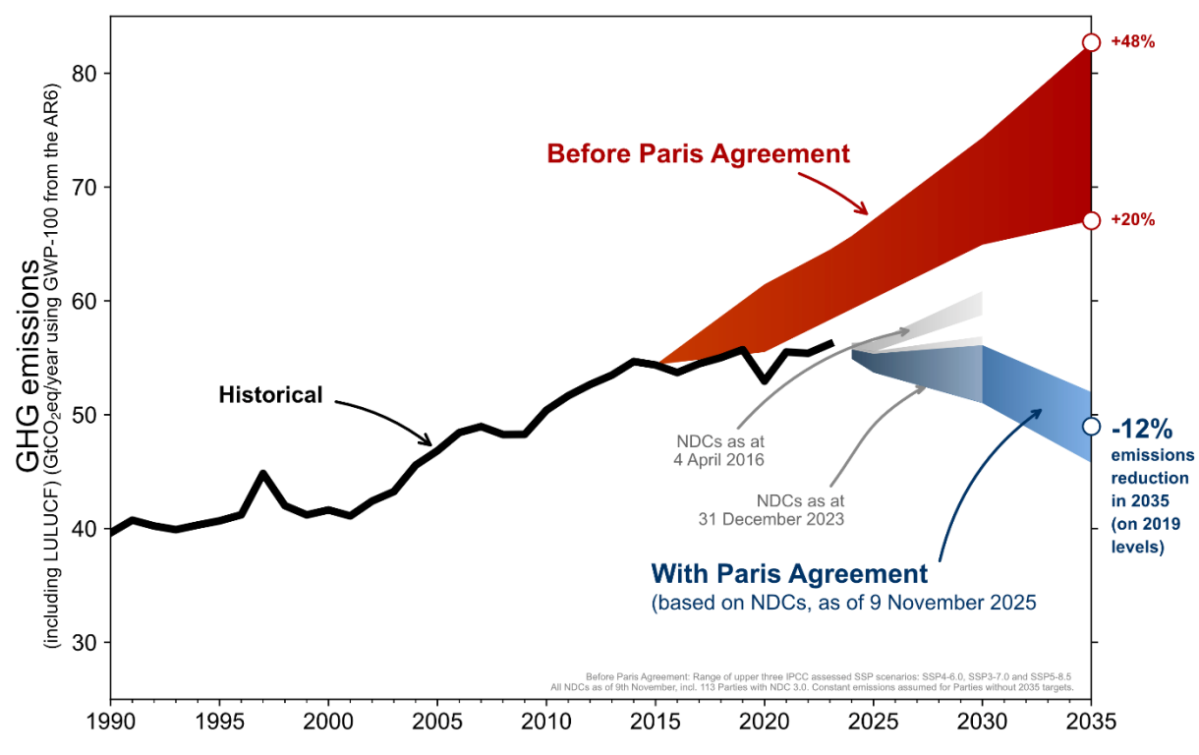

The UNFCCC shared the graph below to illustrate what it describes as the remarkable success of the Paris Agreement. The black line shows historical greenhouse gas emissions, while the red cone shows how those emissions were projected to increase dramatically after 2015. The blue cone showing a decrease in emissions represents where the world appears to be headed today, with emissions peaking and then declining.

The large gap between the two projections, the UNFCCC asserts, is the direct result of policies implemented under the Paris Agreement. In reality, however, the differences between the two forecasts reflect the simple fact that the red cone represents erroneous projections, while the blue cone represents a more updated understanding of where we are headed. The story here is that extreme emissions projections were well off track, and real-world data pointed to a much more moderate future. Spinning that course correction as the result of policy success is not supported by the evidence.

Understanding the misinformation at play here requires a bit of a journey into the details of climate scenarios.

The UNFCCC explains that the red cone in the graph above represents the high and low boundaries of emissions scenarios projecting where the world was allegedly heading before the Paris Agreement. The scenarios are part of a larger group of scenarios developed beginning in 2005 that underpins most climate research seeking to project future climate change and its impacts, serving as the basis for the scientific assessments of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

While these projections represent emissions futures that may have seemed plausible several decades ago, scenario experts have known for a while now that the core assumptions underlying them have turned out to be simply wrong.

The error across emissions scenarios rested on the premise that “long-run growth in future world energy demand must rely on increasing levels of per-capita coal use,” according to pioneering research by Justin Ritchie and Hadi Dowlatabadi in 2017. Coal is by far the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel, and thus projections that assume a dramatic expansion of coal energy into the 21st century will necessarily result in extreme carbon dioxide emissions. But Ritchie and Dowlatabadi explained that the presumption of rapidly increasing coal consumption was inconsistent with energy system trends, based on an untested theory, and repeated errors in energy system forecasts from decades past.

Back in 2017, Ritchie and Dowlatabadi’s analysis may have been debatable. However, by 2020, the evidence that the real world was not following coal-intensive trajectories was undeniable. That year, I was part of a team of researchers, including Ritchie, that compared scenario emissions projections to real-world trends and near-term energy outlooks. We found that Ritchie and Dowlatabadi’s analysis held up, concluding that the trajectory of actual carbon dioxide emissions was far below the extreme climate scenarios based on booming coal consumption.

A robust consensus has developed around this view, with most projections of future climate change suggesting that, on current policies, the world is headed in the direction of a 2- to 3-degree Celsius increase over preindustrial values by 2100—a far cry from the 4- to 5-degree or more increase envisioned under extreme scenarios that we now know were wrong.

The emissions scenario course-correction is today well understood by climate experts. However, the temptation has been strong to spin the course correction as instead representing the effects of the Paris Agreement. For instance, recent reports from the New York Times and Axios commit this logical fallacy by relying on the International Energy Agency’s coal-intensive scenarios in their projections of “where we were going.” We now know that we were never going there.

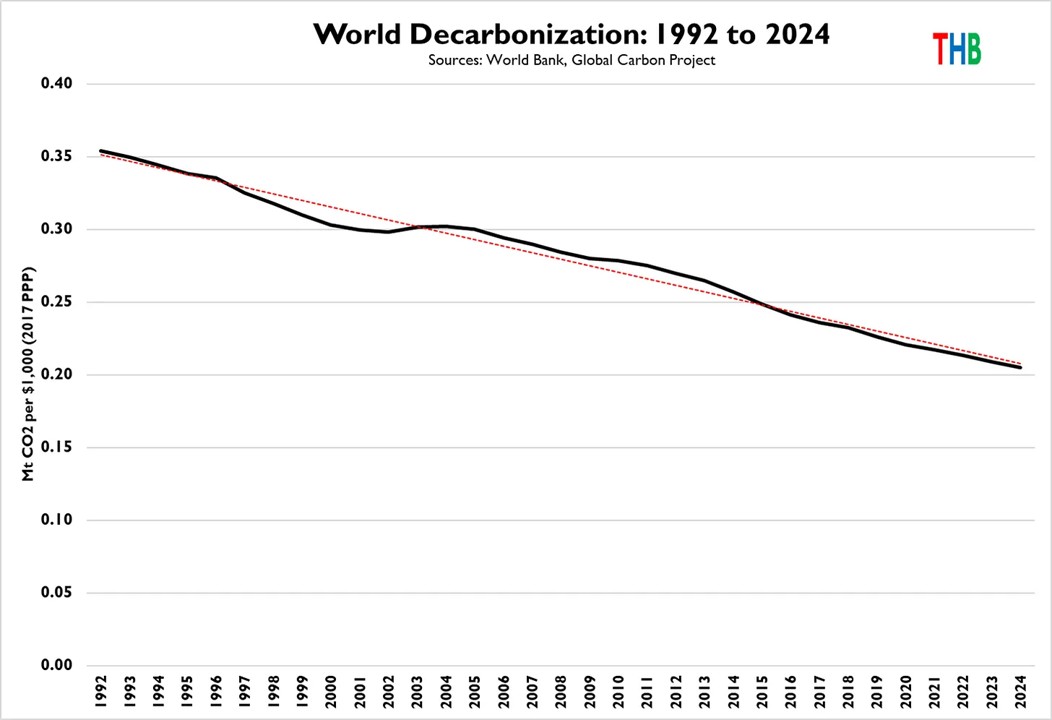

A much better way to evaluate the possible effects of the Paris Agreement on decarbonization is to look at real-world data, rather than to compare how speculative projections have changed. The visual below shows the decarbonization of the global economy (that is, carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels per unit of global GDP) from 1992 to 2024. There is simply no evidence of an acceleration in this metric, which would necessarily follow from an increasing pace of decarbonization, whether driven by the Paris Agreement or anything else.

In fact, comparing the eight years that led up to Paris to the eight years that followed shows no change in global decarbonization. At the national level, the United Arab Emirates, Brazil, and Saudi Arabia were the countries that saw the fastest acceleration of the decarbonization of their economies, which was more than canceled out by the slowing decarbonization of China, Russia, and Indonesia. The United States saw essentially no change between the two periods.

To achieve deep decarbonization, or the reduction of total emissions by more than 80 percent by 2050, would require rates of decarbonization exceeding 8 percent per year, every year. The world is currently decarbonizing at about 2 percent per year, with no signs of progress toward that 8 percent benchmark. In fact, no country has ever sustained a rate of decarbonization even approaching 8 percent per year.

These are sobering numbers that illustrate just how challenging it is to transform the global energy economy. Effective policymaking will depend upon our willingness to hear these hard truths rather than to be comforted by falsehoods.

Even though projections of future climate change have moderated considerably in recent years, the human influence on climate remains real and poses risks to our collective future. Accelerating the pace of decarbonization remains important as we also seek to broaden energy access, secure supply, and reduce consumer costs while limiting environmental impacts.

But we won’t achieve accelerated decarbonization by spinning stories of policy success that simply are not true. As the UNFCCC put it this week, “increasing threats to information integrity represents one of the defining challenges of our time.”

Live Event: Environmental Rules Gone Wild

Join us on Thursday, December 4, at 2:00pm EST for a virtual panel discussion on the weaponization of environmental laws in the U.S. Hear from leading litigators and policy experts as they examine the real costs of excessive red tape and bureaucratic delay—offering front-line insights on the fight for a freer, more prosperous future.

Note: All registrants will receive a recording of the event, so feel free to RSVP even if you cannot attend live.

Policy Watch

- At the Belém climate confab, debate has surfaced over the European Union’s Climate Border Adjustment Mechanism, a fee on the carbon emitted during the production of goods subsequently imported to the EU. Although the measure looks a lot like a tariff, the EU does not characterize it as a trade policy. India, China, and other countries have pushed back against the fee, arguing that the EU is seeking to impose a global carbon tax. A study by the African Climate Foundation and the London School of Economics found that implementation of the duty would disproportionately affect the least developed countries across Africa, with “a moderate to a large negative impact on their GDP by more than 1.5 per cent and up to 8.4 per cent.” Meanwhile, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development has concluded that the measure would reduce global emissions by only 0.54 percent.

- A YouGov poll on what Americans think about energy and climate—organized by my American Enterprise Institute colleague Ruy Teixeira and me and conducted last year—found a remarkable consensus across all demographic groups in favor of pursuing an energy strategy of “all of the above.” Politicians now appear to be taking note. Last week, New York’s Democratic Gov. Kathy Hochul rebuked climate activists: “We need to govern in reality. We are facing war against clean energy from Washington Republicans, including our New York delegation, which is why we have adopted an all-of-the-above approach that includes a continued commitment to renewables and nuclear power to ensure grid reliability and affordability.” Similarly, Rep. Frank Pallone of New Jersey, the ranking member of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, recently argued, “We have an energy crisis, electricity prices for homeowners and businesses have gone up over 20 percent in New Jersey. The only answer is all of the above.” Whether a commitment to “all of the above” unlocks bipartisan energy policy action remains to be seen.

Innovation Spotlight

- Japan is moving ahead with the reopening of the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear plant, the world’s largest nuclear power facility by generating capacity. Following the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011, Japan shut down all 54 of its operating nuclear power plants. But in the years since, Tokyo has brought 11 plants back online and looks poised to continue this reversal. New Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has committed to revamping Japan’s nuclear power industry to bolster the country’s energy security, including by restarting idle reactors.

Further Reading

- During a lecture at Lewis & Clark Law School this month, Ted Nordhaus of the Breakthrough Institute argued that tackling the major environmental challenges of the day requires regulatory policy that is generative, not restrictive. “If you want to stop climate change, you need to build an entire new energy economy capable of providing far more energy to meet the needs of 8 billion people globally, most of whom want to live modern lives just like all of us do. This is not optional. China, India, and other emerging economies are not waiting for our permission to develop,” he said. “So the question for the environmental law profession over the coming decades, in my view, is not what will you stop but what will you build? This, then, leads to a second key question, which is what parts of the enormous environmental regulatory edifice that we have built up in this country are you ready to get rid of so that we can build that world?”

Pacific Legal Foundation has been fighting for freedom since 1973. We sue the government on behalf of farmers, fishermen, teachers, nurses, and entrepreneurs—Americans from every corner of the country and from every walk of life—and we win.