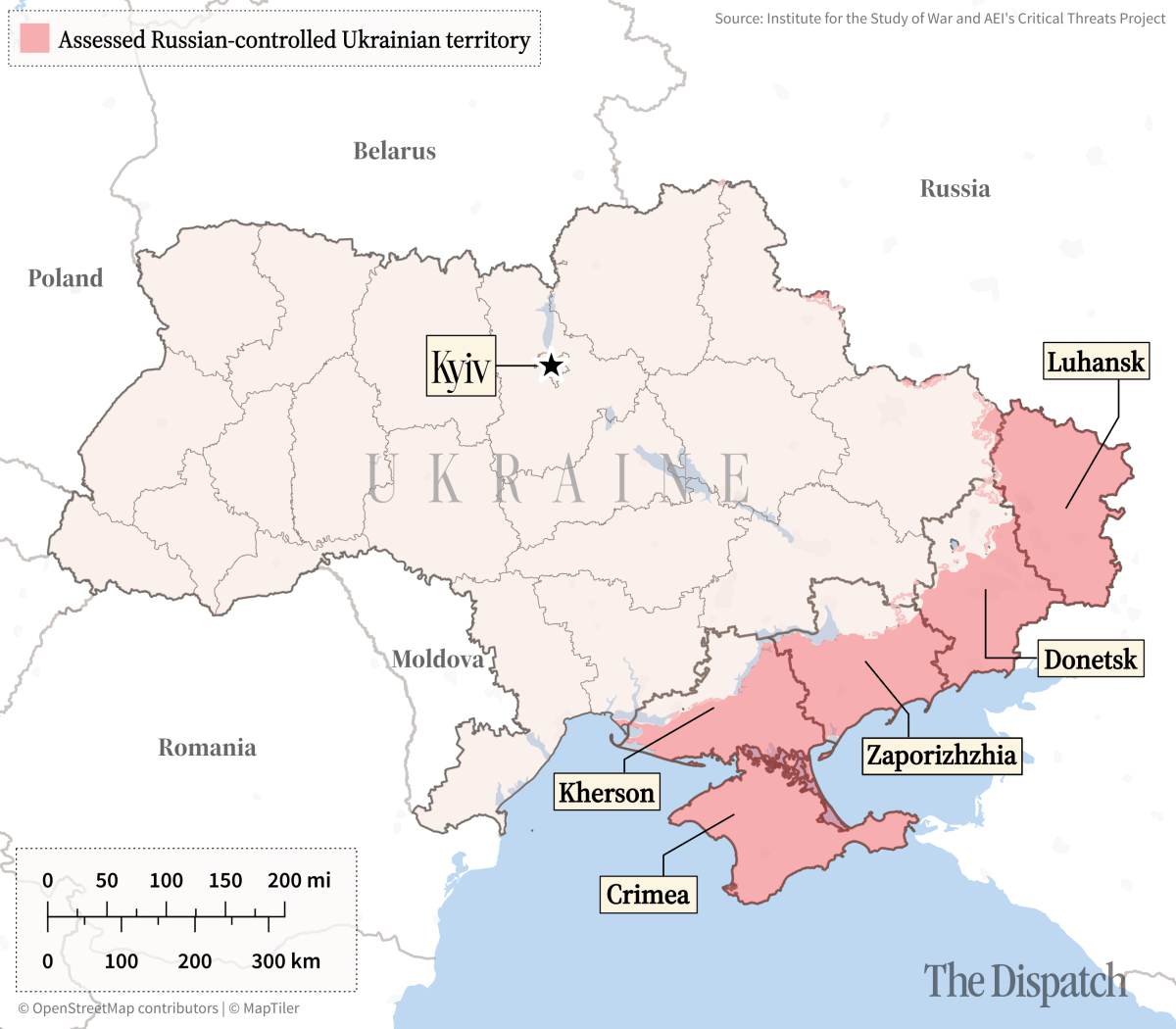

News of the plan broke on Thursday evening, as Axios reported that U.S. and Russian negotiators—primarily Witkoff, Kushner, and Dmitriev, along with Secretary of State Marco Rubio—had drafted a 28-point peace plan; the full text of which leaked the next day. It called for an immediate ceasefire and for Ukrainian forces to withdraw from the remaining parts of the Donetsk oblast that they still control, ahead of a “de facto” international recognition of Russian control over Crimea, Donetsk, and Luhansk (the latter two are known as the Donbas). Front lines in the regions of Zaporizhzhia and Kherson would also be frozen, with “de facto recognition” of Russian control. Russia would withdraw from the territory it controls outside the five regions.

On top of Ukraine ceding territory:

- NATO and Ukraine would both pledge that Ukraine would never join NATO;

- Ukraine would cap its armed forces at 600,000 troops, below the roughly 880,000 it currently fields (it is unclear whether this number includes reserves);

- NATO forces would not be stationed in Ukraine;

- It would be “expected” that NATO not expand further; and

- Ukraine would commit to holding elections in 100 days.

In return, Russia would also be “expected” not to invade its neighbors and would sign a non-aggression treaty with Ukraine, the U.S., and Europe. It also includes a security guarantee, committing the U.S. and allies to determine “the measures necessary to restore security” in the event of Russian aggression.

Negotiators also envisaged a series of economic deals involving Ukraine, Russia, and the U.S. Previously frozen Russian assets would be used to fund Ukraine’s reconstruction and also a joint U.S.-Russia investment vehicle. The U.S. and Europe would also lift sanctions on Russia in stages—though there were few specifics there.

But it’s unclear whether the leaked proposal represented U.S. aims or was an attempt by Kirill Dmitriev to create facts on the ground. Witkoff—in a since-deleted comment on a social media post of the Axios story, which he seemingly had intended to be a private message—wrote, “He must have got this from K.”

And that wasn’t the end of the confusion. While Trump reportedly approved the plan, sending negotiators to Geneva to discuss the details with a Ukrainian delegation, U.S. senators told reporters Saturday that Rubio had assured them that the U.S. did not author its main provisions. Less than an hour after those comments, Rubio said that the U.S. had authored the plan after all, and a State Department spokesperson dismissed the senators’ statements as “blatantly false.”

The proposal isn’t all bad news for Ukraine, said Lawrence Freedman, emeritus professor of war studies at King’s College London and an author of Comment is Freed, which covers the Ukraine war.

“There are odd aspects of it that will annoy the Russians,” he told TMD of the plan, citing the vagueness of the language surrounding sanctions relief, the proposal to use Russian funds to rebuild Ukraine, and the requirement that the Donbas be demilitarized.

The security guarantee is also “more than they [Ukraine] have been offered in the past,” Freedman noted, as it’s the first time that the U.S. and major European powers have all pledged to protect Ukrainian sovereignty. “I don’t think the Russians will accept this,” he said. “There’s too many things at the moment that are too vague.”

But plans can change. Following hours of meetings in Geneva on Sunday, U.S. and Ukrainian officials released a joint statement describing negotiations as “highly productive” and announcing that an “updated and refined peace framework” had been agreed upon.

The revised framework includes 19 points, according to individuals who were present at the negotiations, but it refrains from addressing NATO relations and territorial questions. Those were left undecided, to be dealt with by Trump and Zelensky at a later date—but Zelensky said yesterday that the question of recognizing territory occupied by Russia was the “main problem” in any peace deal, and there is currently no meeting scheduled between Zelensky and Trump.

European leaders are also insistent that they have a say in any final peace deal. On Sunday, the “E3” of Britain, France, and Germany announced their own counterproposal, which builds on the U.S.-proposed framework. It scraps the pledge not to expand NATO, calls for a Ukrainian army cap of 800,000, says that Ukraine can join NATO with “consensus” from members, and says NATO troops can deploy to Ukraine, just not “permanently.” The European consortium also said that any territorial swaps would be negotiated after a ceasefire along the line of conflict, rather than decided from the outset.

“We don’t really care about the Europeans,” one White House official told a reporter last week. “It’s about Ukraine accepting.” But Europe may have some leverage. Collectively, it is now the largest supplier of support to Ukraine, as the U.S. has not passed a new military aid package in Trump’s second term, and most frozen Russian assets are held in Europe.

“They might have a say, maybe they might get some corrections made,” Jim Townsend, a senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security and former deputy assistant secretary of defense for European and NATO policy, told TMD. “But vetoing something? They don’t have that leverage.”

For their part, Russian leaders have been fairly circumspect about the dueling plans. On Sunday, Putin told Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan that the first draft could be the basis for a “final peaceful settlement,” and on Monday, a top Kremlin aide said the European plan was “unconstructive,” while adding that Russia would be open to “many, but not all” of the points in the U.S. plan. Reuters reported this morning that U.S. Army Secretary Dan Driscoll talked with Russian officials in the United Arab Emirates, with more meetings expected today. Another Kremlin spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, said that in the meantime, “We will wait.”

But as Russia waits, the war continues.

Last night, Russian forces once again fired drones and missiles on Kyiv, hitting residential buildings and killing at least six; yesterday, Russian troops continued their advance on the embattled Ukrainian city of Pokrovsk. On Saturday, Driscoll told a group of European diplomats that “the honest U.S. military assessment is that Ukraine is in a very bad position and now is the best time for peace.”

But the situation on the battlefield is more ambiguous, as Rob Lee—a military analyst who regularly tours the front lines—told TMD. Ukraine is increasingly struggling to field full-strength combat formations amid a growing manpower shortage, but Russia is also suffering heavy casualties. The front lines are functionally static, and even when one side punches through, exploiting that opening has proved nearly impossible.

As Robert Hamilton, a military expert and senior fellow at the Delphi Global Research Center, told TMD, “You can’t put a tank battalion or a mechanized infantry battalion out in the open because it’s going to be killed by drones.” The only option is to move forward slowly, in small groups.

Ukraine’s government is also facing political challenges. Two members of Zelensky’s government resigned due to their suspected involvement in a $100 million scheme to siphon money from the state energy firm, and Andrii Yermak—Zelensky’s chief of staff and one of the lead negotiators in Geneva—has been accused of involvement as well. Independent Ukrainian corruption investigators have not named Yermak as a suspect, but an opposition lawmaker accused him of being one of the anonymous conspirators recorded as part of the investigation.

“Citizens demand accountability from President Zelensky, and they want him to be much more decisive in cleaning up his inner circle,” Oleksandra Keudel, a professor at the Kyiv School of Economics, told TMD. “But this wish is not linked to a desire to support or not support President Trump’s proposal.”A large majority of Ukrainians now favor a negotiated end to the war, rather than fighting until victory. But a deal without strong security guarantees remains very unpopular. “People don’t really know what exactly is a good security guarantee, but [they know] it has to be there somehow,” said Keudel.