But this misses the more important part. The primary system really isn’t all that democratic. It certainly looks more democratic than the convention system. It feels more democratic, particularly for those who vote in primaries. But it’s not quite as democratic as all the press coverage and political advertising suggests.

In the 2022 midterms, 8 in 10 Americans did not participate in the primaries. This means, particularly for safe seats, that a tiny fraction of voters decided who was going to be not only their party nominee, but for all practical purposes, who would win the general election. In presidential primaries, the numbers are often worse. In 2012, only 16 percent of age-eligible voters cast a ballot in the primaries. We hear a lot about the crucial role the Iowa caucuses play in the democratic process. In 2008, a highly contentious primary season, Iowa saw record turnout, with 350,000 people showing up. That’s 1 in 6 eligible Hawkeyes. Mike Huckabee won a famously populist upset—with the support of about 2 percent of Iowans. Obama, the people-powered candidate, garnered 4 percent.

Assume similar numbers for the next two contests. Basically, you have to win at least one, but usually two, of the first three states (Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina). If you do that, voters and donors tend to bandwagon around the “inevitable” nominee. You can call that subsequent support “democratic,” but it still means that the party nominations are determined by a tiny handful of voters. And, here’s the crucial point: A great many of those voters don’t like their own party. Think of all the candidates who run against their own party’s “establishment.” In recent years, it’d be harder to think of ones who didn’t. But from Howard Dean to Bernie Sanders, not to mention everyone from Huckabee and John McCain (yes, McCain) to Donald Trump, the schtick has been to “take on” their own party. The data suggest that in many cycles close to half of primary voters are “negative partisans”—meaning they dislike their own party (mostly for not hating the other party more)—while maybe slightly more than a third are “positive partisans,” i.e. they like their own party more than they hate the other party.

People hate on “smoke-filled rooms” because they think such venues give the rich and powerful undue influence over the nominating process. That is surely the case, though it did produce some pretty good presidents. It also produced some bad ones, though the blame for their failures can rarely be put at the feet of Fat Cats and Robber Barons. But the brief against smoke-filled rooms leaves out the fact that primaries are steamy garbage dumps for the same forces. The “money primary” and the “media primary” aren’t pristine processes either. Indeed, the primaries provide a form of “democracy washing” the influence of big money and rampant demagoguery—by the candidates and their donors and media boosters. What the primary system does is cut out the gatekeepers, the institutionalists, the small-r republican figures who care about the integrity of the party, the salience of various unsexy issues, and this thing called “governance.” When the party is in control, it still cares a lot about winning, but it also cares about the long-term viability of the party, its issues, and down-ballot candidates. Congressmen who want to get reelected might want a more boring presidential candidate that will put the party above his own ego and self-interest.

As Jonathan Rauch puts it elsewhere:

Today, both party establishments, but especially the GOP, are largely spectators in the process of choosing their own party’s candidates — a condition unheard of in other major democracies. Because so many primary races are decided by small numbers of voters who tend toward extremism, the system elevates politicians who are not only less experienced, less capable, and less responsible than the ones chosen in smoke-filled rooms, but often less representative of the electorate as well. The role of formal parties is reduced to jawboning, sponsoring direct mail, staging debates, and serving as vehicles for whichever candidates and factions seize the steering wheel.

In other words, a relatively small group of people is still deciding who the nominees are. It’s just not the people who represent the interests and values of the majority of voters or even the majority of Democrats and Republicans. And it’s certainly not the people who run the parties themselves. It’s like giving people who hate McDonald’s the right to vote on corporate decisions, and they make their decisions largely based on the fact that they hate Burger King even more.

Say what you will about the shareholders and franchisees of McDonald’s—many of whom might well hate Burger King—they actually care a lot about the long-term health of McDonald’s. And you know what else? They know something about how McDonald’s operates.

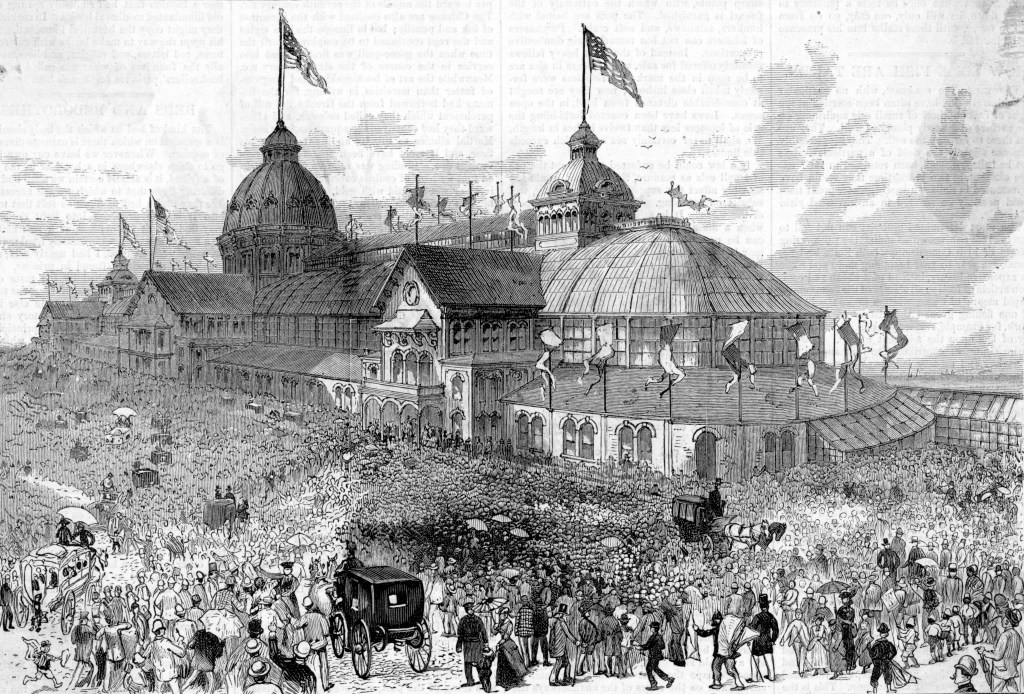

But let’s get back to the 1880 convention, which was oddly smoke-free in the Netflix depiction. The delegates had arguments. They argued for days on end. When they made a bad argument, or supported a bad candidate, they had to come up with better arguments or better candidates. Yes, there was horse-trading and graft in the mix. But there were also delegates who wanted candidates—like Garfield—who would break the stranglehold of the grafters and grifters.

Pre-1972, convention delegates were democratic representatives, too. Not in the constitutional sense, but then again, nothing about our party system has much to do with the Constitution. Yet the delegates represented constituencies all the same. They argued about what would be good for their constituents, their states, and regions.

The delegates voted—yay, democracy!—but the qualifications for voting were far more selective than those for a primary voter today.. You had to have a reason to be a delegate. And while there were a lot of different reasons one could become a delegate, those qualifications amounted to more than just being angry or showing up because you had nothing better to do, unlike today’s primary voters.

And you know what? After the parties decided who to nominate, the American voters got to vote. Because democracies don’t depend on democratic primaries to be democratic.