In 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton delivered the famous “Declaration of Sentiments” to a crowd of women’s rights activists in Seneca Falls, New York. Modeled after Thomas Jefferson’s 1776 declaration, her words included biting indictments of what she described as systemic patriarchy:

The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world.

She went on to relate how women lacked access to divorce, education, employment, and leadership in the church. But the truly scandalizing part came at the end, when Cady Stanton called for women’s voting rights so that they might have the full privileges that citizenship guaranteed. Of the convention’s many resolutions, elective franchise was the only issue that failed to get unanimous support. It would be another 72 years before her call for women’s suffrage was fulfilled.

Often, the history of women’s rights appears to have progressed upon an almost inevitable and predetermined path, when in fact the years between the Seneca Falls Convention and the passage of the 19th Amendment were long and full of political failures. There is no straight line from 1848 to 1920. Instead, the path to women’s suffrage was littered with historically contingent forks in the road.

The vulnerability of women’s suffrage is in part captured by the 19th Amendment’s tenuous ratification. After Congress passed the amendment in 1919 and sent it to the states for ratification, the final opportunity to get approval from the necessary 36 states came down to Tennessee, where Harry T. Burn, a young member of the Tennessee House of Representatives, cast the decisive vote. Having initially voted to table suffrage, resulting in a tie, Burn changed his vote after he received a letter from his mother, Febb Burn, pleading that he support suffrage. He listened to his mother, and despite the political shaming that ensued, he also won reelection. Apparently, women were not going to simply double their husbands’ votes, as some anti-suffragists claimed.

So how does something as significant as women’s suffrage boil down to a vote cast by one state legislator? To answer that question, we can turn to an unexpected place: Wyoming.

Following the Civil War, prominent suffragists had hoped to see universal suffrage enshrined in the Constitution as part of Reconstruction. The desperate need for newly freed men and women to gain political protection, however, pitted questions of race against those of gender, and women’s voting rights lacked a comparable sense of urgency. The provisions in Section 2 of the 14th Amendment to protect voting rights referred to “male citizens”—the first time gender was explicitly used in the Constitution. With the 15th Amendment’s statement that voting rights could not be “abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” black men were enfranchised while the opportunity for universal suffrage crumbled. Effectively, the amendment left women’s voting rights in the hands of the states.

Before finding its way to state legislatures, however, women’s suffrage got its start in the territories. By the time the 15th Amendment was ratified on February 3, 1870, women in the territory of Wyoming already had access to the voting rights that prominent suffragists like Cady Stanton had only dreamed of. Wyoming granted women’s suffrage in December 1869, and Utah followed just two months later.

In the West, movements for women’s suffrage were beset by their own factional divides. Although radicals, Spiritualists, and free-love activists clashed with socially conservative temperance activists throughout the late-19th century, they all agreed that women should have access to the ballot. As historian Rebecca Meade’s scholarship shows, despite the sometimes cavernous divides between these groups of women, together they had one critical advantage that women elsewhere in the country lacked: substantial economic power.

The nature of Western women’s experiences is captured in part by the story of Amalia Post, one of the first American women to serve on a jury. A divorcee who had moved from Michigan to Omaha and then on to Denver, Post eventually settled just 15 miles north of the Colorado border in Cheyenne a year and a half before Wyoming became a U.S. territory in 1868. Having been abandoned by her first husband, she raised chickens to support herself and then loaned money for interest. While Mississippi was the first state to give married women the right to own property in 1839, the 1862 U.S. Homestead Act gave any head of household—regardless of gender or marital status—the right to claim land. When she later remarried, Post took advantage of the economic independence afforded to her by Western states and territories, retaining property in her own name to ensure she would never be so vulnerable again.

For Amalia Post, then, voting rights were part of a cluster of prerogatives that ensured her protection from economic and legal vulnerability—something women keenly felt in the isolation that often accompanied frontier life. Rather than demanding voting rights based on her political activism, her access to the vote made her more politically active, and she became engaged in expanding the franchise to other women. Archivist Claudia Thompson’s work on Post relates how she wrote to her sister, celebrating her newfound rights in Wyoming, where she served on a grand jury and looked forward to voting, despite her husband’s opposition. “I am intending to vote in this election [which] makes Mr. Post very indignant as he thinks a Woman has no rights,” she wrote. We know that Post attended the National Woman Suffrage Association in Washington, D.C., in 1871 and served as Wyoming’s delegate to the organization’s meeting in 1884. She was a Republican while her husband, Morton, was a Democrat.

Post’s story also reveals an important historical detail: Suffrage in Wyoming wasn’t solely the result of women’s activism. The men of the Wyoming territorial legislature were the country’s first to do a peculiar thing—the same kind of thing that Harry T. Burn would do nearly 50 years later—expand the franchise when the existing system had already afforded them the exclusive privilege of elected office. Why take a political risk that threatened their own self-interest?

In Wyoming, the answer was simple: hubris.

As Methodist minister H.C. Waltz explained to his readers in 1872:

Two years ago the Democratic party, then in the majority, passed a law enfranchising the women of Wyoming, but did it all as a joke, supposing surely that the Republican Governor would veto it. But to their astonishment, he accepted it, probably thereby to bring into greater notoriety this young territory, as well as to force his political opponents to father this unpopular law.

When the Democrats then attempted to repeal the law, the governor vetoed the repeal. In short, the post-Civil War suffrage debate that shaped the 14th and 15th Amendments came to roost in Wyoming in an unexpected way. The Republican governor Waltz refers to was John Campbell, an appointee of Ulysses Grant’s administration. The all-Democratic legislature hoped to embarrass him and the Republican values that had extended voting rights not only to black men but also to the Chinese men who were an essential labor force in the West. For Democrats, granting women the vote might also have been an attempt to increase the white vote in the territory.

If the Democratic legislature’s intentions failed, their use of women’s suffrage as a political football represented a larger trend regarding franchise expansion in the American West. Political scientist Dawn Langan Teele explains that all-male legislatures in the West were more open to women’s suffrage in part because the political environment was more competitive. With large labor, Progressive, and Populist party movements, Western states boasted powerful third-party political platforms. To compete, both Democratic and Republican legislators looked to expand the franchise to shore up votes. In contrast, single-party machine politics rebuffed competition in the Northeast and Midwest so that women’s suffrage offered little strategic advantage.

If Reconstruction created terms for postbellum America to continue based on shared male privilege, the people of Wyoming threw a wrench in the gears. They unintentionally set a powerful precedent that other Western states and territories would follow. Utah territory enfranchised women in early 1870 (although they lost those rights in 1887 when the anti-polygamy Edmunds-Tucker Act disenfranchised Utah women, and they did not get them back until Utah became a state in 1896), and Nevada territory followed in 1871. Colorado gave women voting rights in 1893 and Idaho did so in 1896.

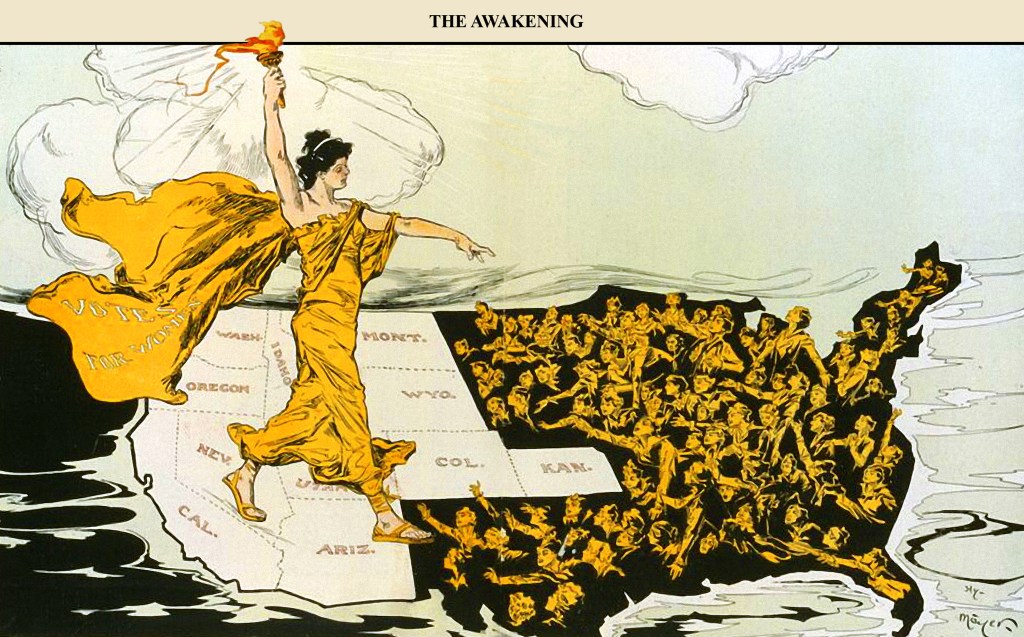

By the turn of the century, Western suffragists saw the vote and their regional identity as deeply tied together. As with Amalia Post, these enfranchised women were called upon to help advocate for the women in the eastern half of the country. One suffrage poster called “The Awakening” showed a torch-bearing woman moving from West to East, reaching out to a black sea of disenfranchised women.

While enfranchisement in Western states revived the national movement, the process was arduous and anything but straightforward. Governors in California and Arizona vetoed women’s suffrage bills in 1893 and 1903, respectively. When California’s women ultimately gained suffrage in 1911, it was thanks to a suffragist-backed Progressive Party victory. If the West’s competitive environment proved more fruitful for suffragists, the 18 years between California suffrage bills shows the challenging work required to achieve political victories.

Today, as our local politics grows increasingly national, it can be easy to forget that by sheer size, our country’s geography forces some element of political heterogeneity on our experiences. Being a Democrat in Wyoming involved a different political calculus than being a Democrat in Tennessee—even if many of the convictions remained the same. The nature of political expression shifted (and continues to shift) based on place.

When it came to renewing the national woman suffrage movement in the 1910s, more than posters connected the Western and national movements. Local strategies honed in Western states also made their way East. When Alice Paul led the first national suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., in 1913, she borrowed a method from suffragists in California. There women learned the value of parade demonstrations from labor organizers after they entered a women’s rights float in San Francisco’s 1911 Labor Day parade. The float organizer, Maud Younger, became a close collaborator of Paul’s and brought numerous organizational skills with her to Washington for the national cause.

You cannot capture the story of women’s voting rights without the pathbreaking actions of women like Cady Stanton and Paul, but you also can’t understand the complicated reasons why men would vote to expand the franchise in the first place without accounting for Wyoming. The latter story helps capture the nuanced, uncertain, and highly detailed work required to effect political change in this country. It also shows passage of the 19th Amendment for what it was—a final victory in a string of hard-won local contests that stretched across this country’s complex political landscape.