Looking for the perfect gift for someone in your life who loves The Dispatch? Look no further. We just got a limited run of hats, notebooks, mugs, and T-shirts, ready to ship in time for the holidays. Check out our new merch and check a few gifts off your list.

Dear Reader (especially those who have already watched Die Hard twice this month),

Before I get started, I’d like to throw my hat in the ring on another subject. I don’t want to steal Kevin Williamson’s thunder by offering some words about words—not to butter him up but he’s hands down more of a hotshot logophile than yours truly—but I think I’m up to snuff in this area too. On a deadline, particularly when I am fed up with politics, I can pull out the stops and fly off the handle with some better-than-average word play. I’m not trying to get your goat. If you find it annoying, I hope you can turn a blind eye to my self-indulgence a bit longer while I wing it. Still, readers’ patience is not infinite. I don’t want to run anyone ragged. The comment section is already lousy with people inclined to blow a gasket over such things, so I’ll cut to the chase and let the cat out of the bag.

I hope a good number of readers have figured out what I just did. The above paragraph contains 21 dead—or mostly dead—metaphors.

Dead metaphors are phrases that have lost, or mostly lost, their connection to their original imagery. Eggheads (another dead metaphor, as “egghead” originally meant a bald person) call this process “semantic shift.” The phrase “time is running out” used to refer to the sand in an hourglass running out of one section, but few people think of hourglasses when they use the phrase anymore. Young people can be forgiven for not knowing why we “dial” a phone number, “drop a dime” on our enemies, or refer to “above the fold” news stories.

I won’t run through all of the dead metaphors above, but I’ll explain some of the fun ones. “Buttering up” comes from the ancient Indian practice of hurling balls of clarified butter at statues of gods to earn their favor. “Getting your goat” comes from the practice of using goats to keep horses calm in the stable—stealing the goat upset the horses. A “deadline” was the perimeter around the Confederate prisoner of war camp in Andersonville, Georgia. Cross one and you could be shot. (Some Dispatch editors believe we should revive that.) “Winging it” originally meant repeating the lines whispered to actors from the wings of the stage. “Hotshots” were heated cannonballs or other projectiles. “Turning a blind eye” is a British naval term, specifically referring to Adm. Lord Nelson’s maneuver of deliberately turning his bad eye to the signal to retreat so he could pretend he didn’t see it. “By and large” is also a nautical term (along with “slush fund,” and countless others). It referred to a ship that could sail with the wind or into it. “Cut to the chase” came from silent movies. Directors would say something like “This scene is boring. Cut to the chase”—as in the car chase or whatnot. “Cat out of the bag” is debated, but one popular theory is that scammers would try to sell a pig in a bag when in reality it was a feline. This is definitely the origin of “pig in a poke.” Oh and “lousy” originally meant, literally, full of lice (“louse” being the singular of “lice”).

Anyway, I suppose you’re waiting for the other shoe to drop (a term that comes from tenement era New York. People could hear when their upstairs neighbor took off their shoes at the end of the day through the thin ceiling. So when you heard one shoe drop, you waited with bated breath for the second one to hit the floor. “Bated breath,” by the way, is a term invented by Shakespeare.

I got to thinking about all of this because I felt like I screwed up the “Ruminant” episode of The Remnant this morning. And so I wanted to take a mulligan and try a different tack (I swear, I’m trying to stop).

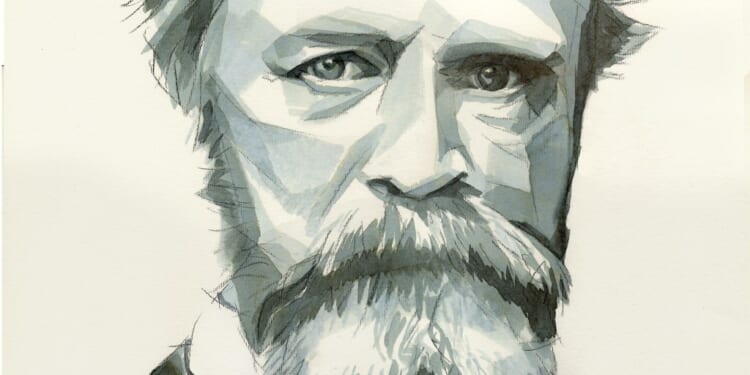

There are few topics I’ve written more about than the “moral equivalent of war.” A very quick recap is in order. The phrase was coined by the American philosopher William James. His idea was that government and society needed to find a “moral equivalent of war” to organize and motivate society. James’ argument was at once naïve and idealistic and coldly realistic, even cynical. Man is a war-fighting creature, according to James. “Our ancestors have bred pugnacity into our bone and marrow, and thousands of years of peace won’t breed it out of us,” he wrote.

War itself is wasteful, destructive, expensive, and cruel. But war was also the source of our greatest virtues—it brought out the best in men (and James was primarily concerned with men). So what “we” needed, James argued, was an alternative or “equivalent,” some other collective cause or endeavor that aroused the self-sacrifice and cooperation we tend to see in times of war. “Martial virtues must be the enduring cement” of society, James argued, “intrepidity, contempt of softness, surrender of private interest, obedience to command must still remain the rock upon which states are built.”

James thought the best candidate for this alternative to war was a battle against Nature. He proposed that “instead of military conscription,” America should embark in “a conscription of the whole youthful population, to form for a certain number of years a part of the army enlisted against Nature.” He wanted a civilian army of draftees logging forests, digging tunnels, mining coal and steel, washing dishes, building roads, etc. In such a program of mass conscription, America’s youth would “get the childishness knocked out of them” and reenter society with healthier sympathies and soberer ideas. “They would have paid their blood tax, done their own part in the immemorial human warfare against nature; they would tread the earth more proudly, the women would value them more highly, they would be better fathers and teachers of the following generation,” he wrote.

The martial type of character can be bred without war. Strenuous honor and disinterestedness abound everywhere. Priests and medical men are in a fashion educated to it, and we should all feel some degree of its imperative if we were conscious of our work as an obligatory service to the state. We should be owned, as soldiers are by the army, and our pride would rise accordingly. We could be poor, then, without humiliation, as army officers now are.

I don’t want to be owned by anything not of my choosing, and any campaign by the federal government to inculcate a sense of being owned by the state or its proxies is illiberal and un-American.

This idea became the inspiration for Franklin Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps, a thoroughly martial enterprise where young men woke to revelry and went to bed after “Taps” was played. In between, veterans from World War I drilled and ordered them about.

But the idea had far wider appeal and influence. The whole of the New Deal was organized as a moral equivalent of war. The National Recovery Administration (NRA) was run by Hugh “Iron Pants” Johnson, the overseer of the draft in the First World War. The symbol of compliance with the NRA codes, which quasi-cartelized American industry, was the Blue Eagle, which FDR likened to military insignia distinguishing friend from foe. In 1933, Johnson organized the Blue Eagle Parade in honor of “The President’s NRA Day.” It was at the time the largest parade in New York City’s history, and members of different professions marched in the “uniforms” of their trades. In Boston, a hundred thousand schoolkids were marched onto the Boston Common and forced to swear an oath, administered by the mayor: “I promise as a good American citizen to do my part for the NRA. I will buy only where the Blue Eagle flies.”

I could go on—and have before. The idea of the moral equivalent of war became part of progressivism’s DNA, in part because the New Deal became part of its DNA. And the New Deal was really—by FDR’s own admission—an application of Woodrow Wilson’s war socialism for purely domestic ends. The “War on Poverty” was an updating of the New Deal moral equivalent of war. Whenever you hear someone say we need a “new New Deal” (or a “Green New Deal”), they’re channeling William James, often without knowing it.

I hate moral equivalent of war arguments. They are an attempt to short-circuit democratic debate by bullying people into compliance with a collective enterprise, whether they agree with it or not. War mobilization is obviously sometimes necessary because war is sometimes necessary. But war-mobilization-without-war of the sort envisioned by James and the New Dealers is inherently illiberal. The military is a necessary institution for protecting domestic liberty; it is not a necessary institution for modeling an alternative to liberty.

But James was right about one thing: War occupies a massive place in the human imagination. The way martial thinking organizes our minds and categorizes our worldview is deeply ingrained in us—not us Americans but us humans. The concept of war ranks with family and light as the prisms through which we explain and understand the world around us. As George Carlin famously recounted, football is drenched in martial terms. But so are politics and business. How many CEOs and political consultants tout The Art of War? Consider the not-quite-dead metaphors that define so much of politics. Ad blitzes and battleground states, air wars and war rooms. “Campaign” is a military term, as are “crossfire,” “collateral damage,” “deploy,” “rank and file,” and others. The reason we have the term “civil engineering” is that until the 18th century, engineering was a military enterprise.

The point here is that war is at once a dead metaphor and a live one. Like an organism that sheds decaying skin or cells as it constantly evolves, war lives in our brains and relentlessly sheds concepts that take root in our minds and language.

But here’s the thing: War is war. It’s not anything else. Legally, philosophically, psychologically, evolutionarily, and morally, nothing is entirely like war. War is sui generis. Policing isn’t war. Politics may be war by other means in a very narrow sense. But in a much broader sense, politics is the alternative to war—not the equivalent. It is the alternative, the substitute. Defeating someone in an election is not meaningfully like killing them, never mind killing your opponent’s voters. When you invoke war as the analogue to something else, you’re trying to steal the authority and permission that war gives. I get the point of “all’s fair in love and war,” but I don’t think that’s literally true. But when we invoke this thinking about things that are not about war or love, we are trying to say that the rules don’t apply.

In 2012, when Barack Obama said in a State of the Union address that America would be better off emulating the military and SEAL Team 6, I was offended. I got a lot of grief for it, but I stand by it. I don’t want the federal government, or its chief executive, exhorting civilian Americans to fall in line as if he is our commander in chief. The president of the United States is the boss of the people in the executive branch and no one else. No mandate gives him the power to command Congress or the courts, or state governors, never mind the American people. War causes people to lay aside their “private interests,” in James’ words, and follow orders. That’s why politicians love to invoke war—to sidestep the messy rules that protect private interests—an anodyne phrase for the “pursuit of happiness.”

Still, Obama’s rhetoric seems trite and harmless now when compared to the martial language suffusing our politics. Historically, the violent radical left—from Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti to the Weathermen and Black Panthers to Antifa—insisted the “system” was at war with them and they were just fighting back. But the system was not at war with them. You can make the case the system was unjust, but injustice is different than war. Today, many on the right use the same sort of language about how “the left” is at war with “us” so we must go to war with them—for our very survival. All of the nonsense-talk about a looming civil war or even a domestic “cold war” is one giant exercise in category errors.

Nowhere is this more obvious than the linguistic and political games being played—quite effectively—by the Trump administration. On immigration, trade, industrial policy, Donald Trump is using, or claiming to use, or threatening to use, authorities granted to the president during war. I’ll spare you an exploration of all the legal stuff—the Alien Enemies Act, IEEPA, emergency declarations, rhetoric about insurrection, sedition, invasion, etc.—because the legalistic maneuvering is simultaneously obvious and beside the point. Trump’s rhetoric about “the enemy within” and similar sinister blather is designed to create a warlike sense of emergency that allows him to disregard legalities. Trump said on Veterans Day in 2023: “We pledge to you that we will root out the communists, Marxists, fascists, and the radical left thugs that live like vermin within the confines of our country that lie and steal and cheat on elections. They’ll do anything, whether legally or illegally, to destroy America and to destroy the American dream.” He added, “The threat from outside forces is far less sinister, dangerous, and grave than the threat from within. Our threat is from within.”

If you take this seriously, ask yourself what permission he was asking for.

War fever is seductive and intoxicating, and that is why Trump is trying to infect everyone with it—not just his supporters but his enemies too. He wants to scare his opponents into acting as if he’s serious with this rhetoric, because he needs his opponents to prove him right.

Trump’s campaign in the Caribbean leeches off of arguments that only make sense if we are literally at war with “narco-terrorists.” But as bad as people trying to sell Americans drugs are—and they are very bad—selling drugs is not an act of war. The administration says these terrorists—just like various criminal gangs of illegal immigrants—are agents of a foreign government, but actually demonstrating this to the public or Congress is a waste of time because such legal niceties are a hindrance when we’re at war. It’s question begging and bootstrapping all the way down. The point of constantly ratcheting up war talk is to grab the power without having to make a reasoned argument for granting him the power. The point is to say anyone who cares about the rules is siding with the enemy in a war that we’re not actually in. Just this week, the White House press secretary endorsed the idea that “Liberals Side with Bloodthirsty Narcoterrorists in Crusade to ‘Get Trump.’”

Crime is bad, but the fight against crime isn’t war any more than the fights against climate change or poverty are wars. But the administration wants to muddy all of that up, sending the National Guard to fight crime and defend the federal government against “the enemy within.” Authorities granted to round up “invading” criminal gangs are melting into authorities to round up immigrants—and even people who look like immigrants. And if you have a problem with that, you’re siding with the invaders, or you too are an enemy within.

William James’ idea was that we can take the bad stuff out of war but keep the good bits. But we can’t. And the problem with thinking we can put a yoke and saddle on war and make it into a pliable beast of burden is that it lets the beast out of its cage. Sometimes we need to let that beast out of the cage and defend American interests, starting with the American interest in protecting liberty and domestic tranquility. But that’s not why Trump is coaxing the beast out of the cage.

He wants to breathe life into the dead metaphor of war.

Stories We Think You’ll Like

Various & Sundry

Canine Update

So we were gone for a week, and the girls were very happy to have a sleepover at Kirsten’s (for the most part) but aggrieved that there were no turkey leftovers. Almost as aggrieved as yours truly. While out West, I got to hang out with Bruno and Penny. Bruno, some may recall, was one of the most handsome puppies I’ve ever met. He is now a mature very good boy. Penny is an elderly sweetheart. But they both had an excellent Thanksgiving. At Cannon Beach, I also met this enormous Maine Coon cat. I didn’t get a welcoming committee video because the dogs came home while I was out. But the morning negotiations have resumed. As has appeasement. And of course, treats. Everyone was very excited about the snow this morning, but Pippa was worried that the mean dogs would use it for cover.

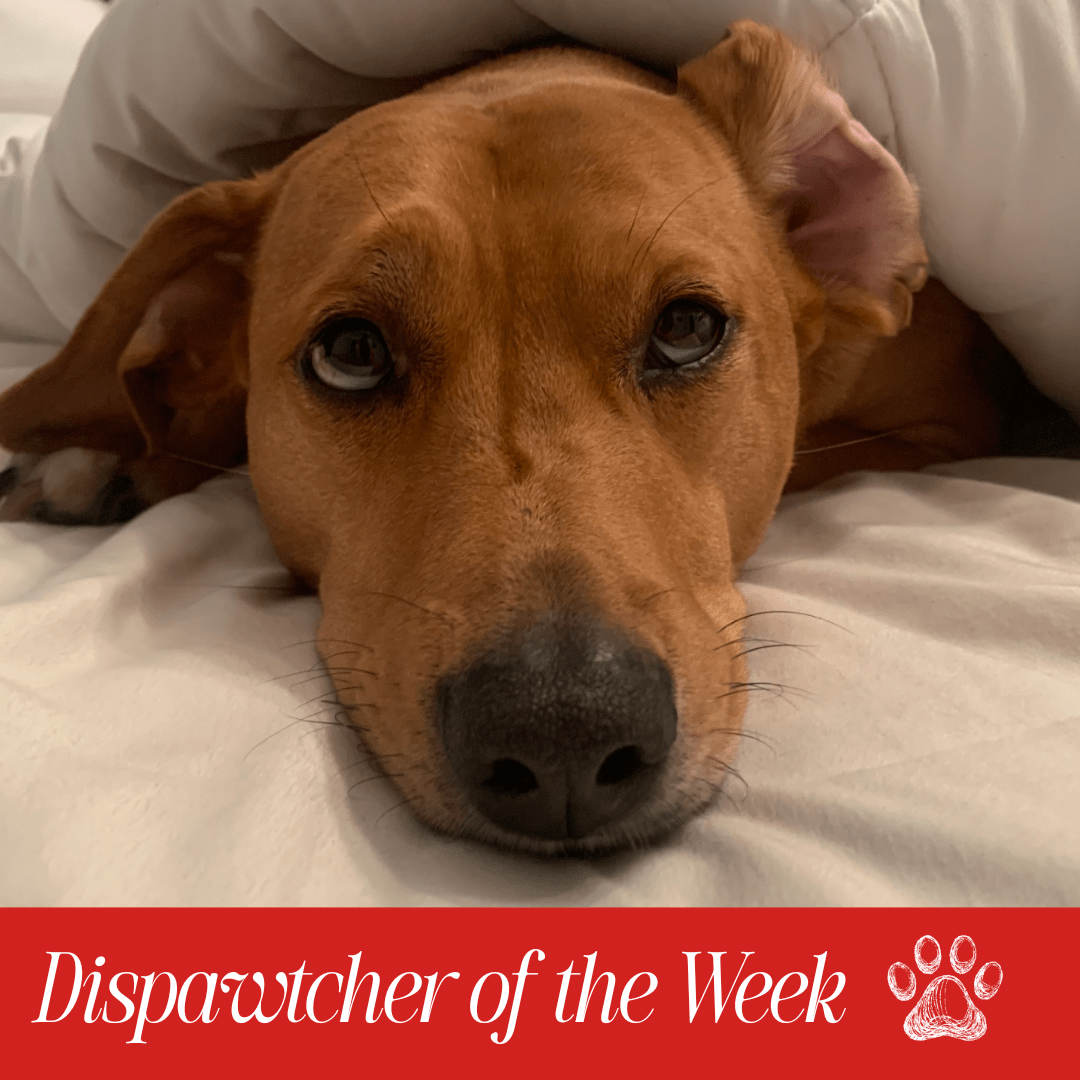

The Dispawtch

Member Name: Kathryn Bowser

Why I’m a Dispatch Member: My brother knew I had been feeling politically homeless for a while, but especially once 2020 hit. He was the one to tell me about The Dispatch. It was refreshing to find a home, where ideas were thought out and thought through before being spat out.

Personal Details: I taught middle school social studies last year, and little did my students (or their parents) know they were being taught from many of the writings of The Dispatch when we touched on current events.

Pet’s Breed: Generic (but amazing) Brown Dog

Pet’s Age: Approximately 9-10

Gotcha Story: I got Watson off of Craigslist. He had been a stray, and the woman who found him worked for two months to find his owner before looking to rehome him. When I went to her house, her two little dogs barked like crazy and jumped all over me. Watson came over, calmly sniffed me while wagging his tail and then walked away. I immediately thought, “He’s perfect.” I took him home that day, and he’s been my best buddy ever since.

Pet’s Likes: Watson loves toys. Whatever toy is newest is his favorite, but he continues to play with all of them. Likes also include popcorn, hunting houseflies, being under blankets, sunbathing, and sleeping in.

Pet’s Dislikes: Getting up in the morning, the rain, things that beep, and when I leave the house.

Pet’s Proudest Moment: Probably when he got out of a friend’s fenced-in yard and traipsed through the muddy woods, tracking all kinds of critters, having the time of his life, while I stumbled after him. When he finally got tired and sat down, I caught up and squatted in front of him and said, “We’re never doing that again,” and we haven’t. But he had a blast. Bad Pet: Sometimes people sit on Watson’s spot on the couch, and he stares at them until they move. I think he’s completely in the right, but others think he’s a bit pushy.

Do you have a quadruped you’d like to nominate for Dispawtcher of the Week and catapult to stardom? Let us know about your pet by clicking here. Reminder: You must be a Dispatch member to participate.