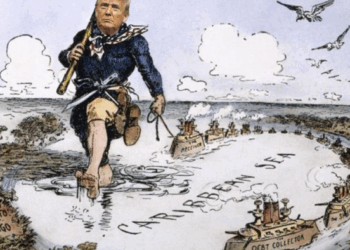

Since the Washington Post first broke the story behind the messy and complex first attack in what would later be called Operation Southern Spear, both defenders and critics of the effort to target Venezuelan-linked narcotics smugglers have fixated on portions of the story that bolster their point of view. Initially, this information battle was fought, in part, through proxies, with various anonymous sources throughout the Trump administration providing their interpretation of events to the Washington Post and the New York Times.

On Thursday, however, several members of the House and Senate heard directly from the source: Adm. Frank “Mitch” Bradley, the former head of Joint Special Operations Command who oversaw the execution of the September 2 strike. Following this closed-door testimony, lawmakers, largely along party lines, continued to offer conflicting interpretations of the events. However, some agreement has emerged on several facts that confirm or clarify the Post’s initial reporting.

But even as concrete details about Operation Southern Spear’s opening strike come into focus, ambiguity about the purpose and nature of the military campaign in the Caribbean and the East Pacific persists. In the conflicting reports about the September 2 attack, the absence of clear directives from the Trump administration has become obvious.

Despite the initial flat denials from the Department of Defense, we now have a confirmation of several key events in the reported timeline. Namely, the initial missile strike on an alleged drug smuggling boat killed nine of the 11 personnel aboard; there were two individuals among the wreckage; and Adm. Bradley ordered a second strike that killed the survivors.

There also seems to be clarification on the orders Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth gave prior to the strike. Bradley testified that Hegseth did not give a specific directive to leave no survivors, but rather directed Bradley to kill everyone named on a list of approved targets—a roster that apparently included all 11 aboard the ship struck during this operation. Whether or how the identities of these 11 were confirmed before the strike remains uncertain, as does the legal justification for placing the individuals on the military target list. It’s also not yet clear whether Bradley used the survivors’ presence on the target list as his primary justification for the follow-up attack, but the earliest reports of his testimony suggest he determined that the two crew members remained a threat and, as such, ordered a second strike that he felt was justified.

But there is still significant disagreement over whether this line of thinking is credible. Bradley’s testimony seems to posit that because the two survivors may have tried to upright the debris, they intended to recover the illicit cargo, continue their mission, signal to other drug craft (which were reportedly not in the immediate proximity), or radio them (with radios they did not have), and therefore posed an immediate threat to the American people.

Hors de combat, prohibitions against attacking combatants who no longer pose an active threat, have special provisions for those who are trying to survive a sinking ship. The Pentagon’s Law of War Manual specifies that individuals “who have been rendered unconscious or otherwise incapacitated by wounds, sickness, or shipwreck, such that they are no longer capable of fighting” are protected.

This standard is not unique to the U.S. military; attacking shipwreck victims has long been forbidden under international law. The Nazi submarine commander who issued the so-called “Laconia Order,” which forbade German vessels from rescuing survivors of maritime attacks, faced trial after World War II. Eighty years ago last month, a U-boat captain who killed survivors in the water was executed for his crimes. Similarly, the Japanese Navy committed atrocities by firing on and killing several survivors of ships they had sunk.

In the aftermath of Bradley’s testimony, there have been mixed interpretations as to how these unique protections apply and whether they were violated. Democrats Rep. Jim Himes and Sen. Jack Reed both characterized footage of the follow-up strike as incredibly disturbing, and one person who viewed the video is reported to have gotten physically ill watching it. GOP Sen. Tom Cotton, on the other hand, said he viewed the video and believed the two survivors were trying to “stay in the fight,” although his account seemed to wither under scrutiny during a Friday appearance on CNN.

But this back-and-forth is beside the point. The protections of hors de combat endure unless and until the parties in question conduct an overt act to negate them—such as feigning surrender and then resuming an attack—not an act that under any rational view would be an attempt at survival. At one point in the footage, the survivors can reportedly be seen waving at U.S. aircraft in an apparent plea for help.

Adm. Bradley, a former commander of SEAL Team 6, has no doubt conducted and approved hundreds of targeted attacks during the global war on terror. Many of these operations may have involved reattacks if survivors of the initial strike continued to harbor hostile intent. And therein lies the rub. The strikes of the wars in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, and other theaters of the global war were almost entirely against land-based targets who, after an initial attack, could continue to maneuver.

If a first strike disabled an enemy combatant’s Toyota Hilux, they could potentially continue the fight on foot. Two individuals clinging to wreckage in the Caribbean are not in a similar situation, which is exactly why shipwrecked crew are afforded special protections. In other words, U.S. Navy sailors in lifeboats after their ship has sunk and U.S. Air Force pilots ejecting from a damaged aircraft are considered out of the fight; U.S. Army tank crewmen bailing out of a damaged M1 Abrams are typically not—they have simply become dismounted infantry.

But Southern Spear is not the global war on terror, nor is it a traditional conflict against uniformed military. Therefore, the Defense Department would have done well to clearly outline Adm. Bradley’s specific legal and operational guidance in advance of the campaign’s start. These operations, as Hegseth himself noted, often take place in situations of confusion and ambiguity. Adding further confusion and ambiguity through vague guidance is anathema to successful operations in conflict. Without a clear understanding of leadership’s goals, all variables within an already confusing situation remain unfixed, with decisions made in the moment and potentially unanchored to larger national security, legal, and cultural guiding principles.

The fact that survivors of subsequent Southern Spear strikes have been recovered instead of targeted suggests the administration’s realization that the initial approach was not appropriate, and the fact that these survivors were repatriated instead of arrested suggests that perhaps the clear evidence of their criminal behavior is not as ironclad as we have been assured. Both of these issues should have been anticipated and planned for in advance.

Determining the facts of this incident matters. But equally important is understanding its moral repercussions. It may be easy, as many of the administration’s defenders have sought to do, to dismiss the killing of individuals allegedly profiting from the death and suffering of American addicts. However, this is just the latest example of ethical shading wherein a “common sense” result suggests the United States doesn’t need to stop and examine the process by which we achieved that result.

Consider the case of Anwar al-Awlaki. Because al-Awlaki was an al-Qaeda leader, few objected to his killing via a targeted drone strike in 2011. But he was also a U.S. citizen, meaning the president ordered the death of an American without so much as notifying anyone outside the executive branch. Process, laws, and guardrails exist for a reason and prevent flawed humans from making unethical, if well-intentioned, decisions.

The administration should provide a full accounting of what happened on September 2, both by releasing the full video and by making outgoing Southern Command head Adm. Alvin Holsey available to testify, not only on what he witnessed regarding the strike itself, but also on the nature of Hegseth’s guidance before and during the operation. Whether it’s killing an American citizen without due process or ordering the deaths of criminals deserving of protection under U.S and international law, the more we ignore these boundaries, the easier it becomes to do so in the future.