Four steps.

The first step in any self-defense analysis is the “self” part. You’re entitled to protect yourself from an aggressor. The aggressor in this case is drug traffickers hoping to smuggle cocaine into the United States.

But the traffickers targeted on September 2 weren’t headed for the U.S. They were reportedly en route to rendezvous with a larger vessel destined for Suriname, and “trafficking routes via Suriname are primarily destined for European markets” per officials who spoke to CNN. Secretary of State Marco Rubio admitted in the first hours after the strike that the boat was “probably headed to Trinidad or some other country in the Caribbean” before suddenly and conveniently changing his tune the next day.

At best, it seems, the double-tap operation was a case of the White House defending Europe from drug dealers, which isn’t self-defense. (Or “America First.”) There’s even a report that the boat “turned around before the strike,” although it’s not clear why or what its new destination was.

The next step has to do with the nature of the threat. If an aggressor is using force against you, you get to use force in kind. Battlefields are examples of mutual self-defense at an industrial scale: In a kill-or-be-killed situation, soldiers are legally and morally entitled to prioritize their own safety by killing.

That explains why the White House is straining so hard to reimagine drug trafficking as a form of war by other means. We’re now in an “armed conflict” with drug cartels, the president informed Congress a few weeks after the September 2 incident. And those aren’t smugglers we keep blowing up, they’re narco-terrorists.

The problem, as Andy McCarthy noted, is that there’s no battle on this supposed battlefield. No one is firing at the U.S. Navy in these Caribbean operations, least of all two survivors perched precariously atop a piece of speedboat wreckage, so American sailors aren’t faced with a kill-or-be-killed scenario. Nor are these so-called narco-terrorists trying to kill U.S. civilians, as actual terrorists are, since drug dealers don’t typically aim to off their own customers.

The third step has to do with whether a threat has been fully neutralized after using defensive force. Soldiers aren’t allowed to target enemy combatants who are wounded—unless those enemies are fighting on despite their wounds. As long as they continue to pose a danger, they’re fair game despite their injuries.

No wonder, then, that the White House has spent the past week spitballing theories that the two shipwrecked survivors on September 2 were still “in the fight” somehow when they were killed. They could have radioed for backup. They could have continued the mission by salvaging the drugs still aboard the wreckage. They weren’t incapacitated.

They didn’t radio for backup, though. And if you think that ship was in any condition to move forward after being hit, go watch the video of the initial strike that disabled it. Reportedly the two survivors hadn’t even managed to turn the piece of capsized boat to which they were clinging right-side up before they were struck with the double-tap missile. They were actually seen on camera waving to something overhead, possibly to a U.S. aircraft in hopes of rescue, shortly before they were killed.

“The broader assumption [naval officers] were operating off of was that the drugs could still conceivably be on that boat, even though you could not see them,” Democratic Rep. Adam Smith told The New Republic after briefings last week, “and it was still conceivable that these two people were going to continue on their mission of transmitting those drugs.” That sounds like the Navy decided the survivors were still “in the fight” because they could potentially return to it—the logic of which, if taken seriously, would make all but the most grievously wounded combatants fair game for a double-tap in the name of self-defense.

The fourth step in self-defense analysis is less ethical than prudential. Even if the circumstances entitle you to use lethal force to protect yourself, it’s foolish to do so if you have reason to think you’ll be safer by not using force.

That is, if the goal of this Caribbean campaign is to end the flow of cocaine into the U.S., one would think the Navy would have been keen to interrogate the two shipwrecked survivors and use the information to roll up bigger fish in the trafficking network. Who did they work for? Who commands the boat headed for Suriname that they were supposed to link up with? Do they have contacts inside the United States? Are they attached to anyone in the Venezuelan government?

Blowing them up on specious grounds that they were still “in the fight” is like seizing a wounded al-Qaeda lieutenant circa 2002 and executing him on the spot instead of whisking him off to the CIA for interrogation. It’s not what you do if you’re serious about eliminating a wider threat.

Outside the law.

I think the president is constantly looking for new ways to justify using extra-legal force to accomplish his goals. His belief that rules and norms restrain state violence too much is a longtime hobby horse, but Americans are instinctively apprehensive about it. To make them more comfortable, he needs to frame his argument in a manner that appeals morally to everyone at a gut level.

Self-defense is that argument. We all recognize that the law isn’t always available to intervene when someone is threatened. Sometimes they need to take matters into their own hands and counterpunch.

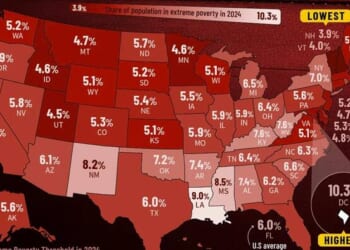

That’s why Trump has begun to reframe the Caribbean campaign in terms of American lives saved instead of foreign lives taken. “Every one of those boats is responsible for the death of 25,000 American people, and the destruction of families,” he said recently. It’s an absurd estimate for a drug like cocaine, but his moral logic is straightforward. They’re killing so many of our people that we can’t wait for the law to deal with the threat. We must act. One of his most ardent fans has even begun comparing coke to a “chemical weapon.”

The thing about self-defense, though, is that it isn’t—or isn’t supposed to be—truly extra-legal. The act itself may occur in a momentary legal vacuum, but that vacuum is quickly filled afterward by relevant legal authorities inquiring about the propriety of the violence. Was the person’s use of force to defend himself reasonable? Was it proportional? Was it necessary? Was it a war crime?

What Trump is trying to do is widen the aperture on self-defense to the point where all of those usual expectations associated with self-defense go by the boards.

For instance, when Karoline Leavitt justified the September 2 strike as a matter of “self-defense,” she obviously wasn’t talking about the legal vagaries of combat in the Caribbean, such as whether the Navy was truly in a kill-or-be-killed situation. She meant “self-defense” in a broad nationalist sense: To defend its citizens from the scourge of drug addiction, the United States can and will use deadly extra-legal force against traffickers.

That’s as far as any “reasonableness” inquiry should go, she seemed to imply. It’s reasonable to counterpunch against drug dealers, period—times 10, in this case.

Considerations of intent and proportionality also dissolve in this broad nationalist understanding of self-defense. Normally, you can’t use lethal force to protect yourself from someone who’s using less-than-lethal force against you; a slap in the face doesn’t justify a stab in the throat. Under Trump’s math, though, the U.S. Navy could kill many thousands of unarmed drug traffickers before the moral scales on proportionality would balance—even if no Navy service member were ever to have a shot fired at them by one of their targets.

“So? We drone jihadis overseas even though they’re unarmed at the time and pose no immediate threat to Americans,” you might say. Right, but those drone attacks aren’t extra-legal. They were authorized by laws targeting al-Qaeda and other terrorist groups after 9/11. And those jihadis do intend to murder Americans eventually. The same isn’t necessarily true of drug dealers, who have compelling financial reasons not to want their American clients dead.

Treating drug trafficking as a form of war instead of a form of crime is Trump’s way of brushing aside these distinctions and avoiding the legal protections to which criminal suspects are normally entitled. He can’t have cops fight drugs here at home by positioning police snipers on rooftops and picking off people from afar whenever they see a suspicious transaction going down. So he’s doing the next best thing: He’s getting the navy to do it before the dealers make it here. Or make it to Suriname. Wherever.

He doesn’t even have the usual excuse in self-defense cases that force was necessary because the law wasn’t present to intercept the threat. The law is present: Until recently, the Coast Guard would be tasked with interdicting these traffickers and arresting them. And surely our much better-armed Navy, which has a major presence right now in the Caribbean and which is close enough to the action to have rescued survivors of other boat strikes, could interdict smugglers en route instead of slaughtering them.

Frankly, I’m not sure if the smugglers are the designated “enemy” in this operation or if the drugs, an inanimate object, are. Rep. Adam Smith says he was told in a briefing that the two survivors killed in the September 2 double-tap strike were deemed still “in the fight” because usable cocaine could still have been present in the part of the boat they were clinging to. The Navy ended up using no less than four missiles to sink the boat even though all crew members were dead after the first two, keeping up the barrage until every last trace of nose candy was at the bottom of the sea.

This latest chapter of the war on drugs really is a war on drugs, apparently, in which “self-defense” requires firing on the cargo itself until it’s obliterated. Any human beings in the blast range were collateral damage.

Preventative.

In the end, the Caribbean operation is the foreign policy equivalent of one of those domestic “emergencies” the president is forever declaring in order to access extraordinary, otherwise extra-legal powers. The closest thing available to him in declaring an “emergency” abroad is an authorization to use military force from Congress, and that’s not happening in this case. So Trump has authorized one himself, sort of, and plans to bootstrap every shady thing he does in the Caribbean going forward into the concept of “self-defense” to cope with the crisis.

He’s counterpunching by waging a preventative war, in other words, ironically the very thing the neocons despised by the president’s base claimed to be doing when they invaded Iraq in 2003. Trump at least has real, actual U.S. overdose deaths to rationalize his actions, unlike the ultimately fanciful risk of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction. But he’s missing everything else—legal authority, a military threat rather than a criminal one, and an enemy who regards Americans as an enemy rather than a market.

Like every bully who fancies himself a “counterpuncher,” I suspect he relishes the extra moral license for ruthlessness that the pretense of victimhood grants him. To the president and many of his supporters, the fact that Marjorie Taylor Greene lives in fear for her life after crossing him isn’t bothersome because, supposedly, she threw the proverbial first punch. She’s a “traitor” who criticized the president repeatedly. Now he gets to hit back—and he doesn’t need to do so proportionally.

When your enemy picks a fight, you’re entitled to finish it and to be ruthless about it (“times maybe 10”) to teach them a lesson. And the Caribbean won’t be the last time we see that logic used, I suspect: Once fentanyl takes its rightful place as top priority in the war on drugs, Mexico is in the crosshairs. And given the antipathy Trump has always had to illegal immigration, that counterpunch promises to pack a wallop.