A few years ago, I worked with a young woman whose American mother was the child of a lapsed Mormon and a Jew, and whose father was a Muslim from Morocco. She is married to a Hindu immigrant from India. “You are the future,” I said after I stopped marveling at her pedigree.

The United States has consistently moved toward ever more intermixing: According to one measure, white people made up 84 percent of the United States in 1965; in 2023, it was 58.4 percent. For the few paranoid white males who shout, “We will not be replaced,” the news is bleak: They are already replaced. Over the long term, this trend would seem unstoppable. But now, in the U.S. in particular, a major pause seems to be underway.

The Trump administration seems on a path to all-out war against immigration. Calling Somalis “garbage,” using the word “leeches,” halting immigration applications by Afghans, threatening to denaturalize those who are already citizens—all in addition to the masked ICE raids—represents a darkening turn from what started out as the second Trump administration’s promise to secure the borders. Now hostility towards all immigration, both legal and illegal, seems on the verge of becoming official policy; indeed, the State Department recently said on social media that “mass migration poses an existential threat to Western civilization.”

It’s unclear whether the government’s hardline rhetoric has had an effect on the average American’s perception of immigrants. But even if nothing has changed yet, could there be a belief in this administration that a large portion of the American public will be persuaded to let go of a decades-long pride in the U.S. as a “nation of immigrants” and embrace an extreme hostility towards immigration? Will the Trump administration’s immigration policy stop a more integrated and diverse world from coming into existence?

The movement of people began when the earliest humans learned to walk. For hundreds of thousands of years, people have migrated. The first migrants were in search of a better food supply, and that basic instinct for survival continues to motivate migration, whether the trigger is hunger or politics. Some migrations, like the Atlantic slave trade, were involuntary; some, like the movement of Hindus and Muslims after the Indian Partition in 1947, were both voluntary and involuntary. And some, like the “great migration” of black Americans from the South to the North, which lasted roughly from about 1910 to about 1970, were a combination of seeking economic opportunity and escaping oppression.

As people move to new places, they come into contact with people who are already there. Throughout history this often led to violence and competition, but it also led to positive change. Isolation tends not to foster change; on the contrary it leads to stagnation, reducing the need to adapt and innovate. In short, we would not be where we are today without migration. As a recent essay published by the International Monetary Fund puts it, migration, in a sense, is human history:

The history of migration is the story of humanity and its progress. It’s a story of peaceful cooperation and exchange, but also of violence. Terrible things have been done to compel people to migrate against their will. Yet despite the suffering, migration remains the key to the success of our species…People on the move carried with them vestiges of old lands and past lives. As they ventured farther from their homes, they encountered previous settlers who had accumulated different habits, technologies, and economic activities. They traded goods and shared ideas, like pollinators of human progress.

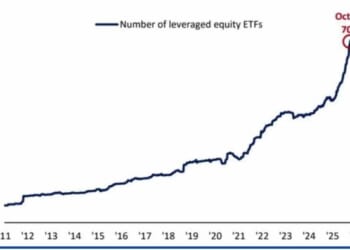

Today, migration is taking place at a pace and in ways and numbers never before seen. Last year more than 300 million people were considered migrants by demographers, an increase of 10.5 percent between 2020 and 2024. They migrate legally and illegally, voluntarily and forcibly, by boat, on foot, and by air. An hour spent in any major world airport reveals a kaleidoscope of races, nationalities, costumes, and languages shifting places.

Virtually everyone in the U.S. today knows someone, has hired someone, or works with someone who is an immigrant, or has someone in his or her family who is or was an immigrant. A few fairly prominent examples: President Donald Trump’s mother and his first and third wives, Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s parents, FBI Director Kash Patel’s parents, Secretary of Labor Lori Chavez-DeRemer’s father, administrator for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Mehmet Oz’s parents, and New York City Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani.

And every day, “native born” Americans see that the majority of people in many big cities who fill in potholes, do construction work, landscape, mow lawns, and paint houses tend to be immigrants. A glance at their work at 7 a.m. in the cold and the rain shows that they are hard workers, and most of those who want to come here, whether to escape persecution or to fulfill a dream of economic opportunity or education, tend to be risk-takers, and in a way courageous. It is not easy to leave one’s home. Just as not everyone in the world is an entrepreneur, just as not everyone in the world can sing and dance, not everyone is cut out to migrate.

Daily observations and experiences like these explain why nearly 80 percent of Americans say immigration is “a good thing” for America, according to Pew, and why, according to New York Times columnist David Brooks, “two-thirds of them want a more ethnically and racially diverse nation than exists even now. A majority of white Christians have a multicultural conception of America. Only a tiny percentage believe in the ‘great replacement’ theory. Only 1.1 percent believe that America should be ethnically and racially homogenous.”

Given such data, most Americans probably have enough common sense to see that the statistical distribution of criminals and rapists among immigrants is not really so different from the distribution of similar types among the “native born” population. Indeed, data on recent ICE raids show a very small percentage of criminals. And of course, there are bound to be some bad apples in any system, as is the case of the Afghan immigrant allegedly responsible for the Washington, D.C., shooting of National Guard troops on November 26.

And while much of the U.S. population supports a tougher stance on immigration, as the 2024 election demonstrated, at its core that support embraces the distinction between illegal immigration and a reasonable, sane and efficient system of labor migration (including H1-B vias), and asylum.

But now, the U.S. government has thrown out all such distinctions. Immigration, all of it, all the time, legal and illegal, is now apparently a threat to our existence.

Words like “threat” and “existence” are meant, as in all propaganda, to tap into the most primitive and base instincts in human nature. They are meant to trigger and unleash latent fear, as well as baser feelings of envy and jealousy. While it is possible that such blatant hostility towards immigrants may cause a backlash, there is also the very real danger that we are on a slippery slope towards events reminiscent of many the world has seen before (including the round up and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II). After all, as German Sociologist Georg Simmel pointed out in 1955, hostility towards others can come about with “uncanny ease.”

As Simmel said: “It is usually much easier for the average person to inspire another individual with distrust and suspicion toward a third, previously indifferent person, than with confidence and sympathy.” He went on: “What is embittering and gnawing to the jealous individual is a certain fiction of feeling—no matter how unjustified or even nonsensical it may be—that the other has, so to speak, stolen… from him.”

But these baser instincts can flourish only when there is fertile ground in which they can grow. In the present context of economic insecurity, polarization, and ominous changes wrought by technology, many people seem to feel a loss of control and a loss of agency and power, if not identity. For many, it seems as if the underpinnings of society are cracking. In such a time, people are ripe to scapegoat, and immigrants, especially those who look, dress, or speak differently, are easy targets. The immigrant is easy to see as less legitimate than those who are already here; it can be easy to see the immigrant as a leech, someone who gets a benefit that is somehow unearned, who takes something away from us.

The lofty exhortation from many that “this is not who we are” could for the time being turn out to be entirely too optimistic. If the American public fulfills Simmel’s dictum that one can turn hostile with “uncanny ease,” then we are indeed at risk of this being exactly who we are. But it is also possible that the utter recklessness of the Trump administration on immigration these last weeks will, like a fever breaking, cause Americans to come back to their senses. Time will tell.